It is said that periodic episodes of small forest fires prevent the big ones, and smaller avalanches prevent the big ones. On the same lines, it can be argued that periodic episodes of equity market corrections and small recessions prevent the bigger crashes and recessions. In each case, the small episodes clear out the excesses and fault lines that continuously develop in any system and prevent their accumulation.

However, for a variety of reasons, over at least the last two decades, central banks and governments in the developed economies, especially the US, have pursued policies that have sought to prevent even such small episodes. This has led to an accumulation of excesses in the dark corners of the financial markets and the economy, whose implosion may be only a matter of time. The likes of an AI-led investment boom can only postpone the inevitable.

Tej Parikh has an excellent column which explains how an extended period of monetary and fiscal accommodation has contributed to plentiful cheap financing, eroded financial market discipline, kept zombie companies going, lowered business entry and exit, delayed recessions, and led to the accumulation of ever-increasing risks across the economy.

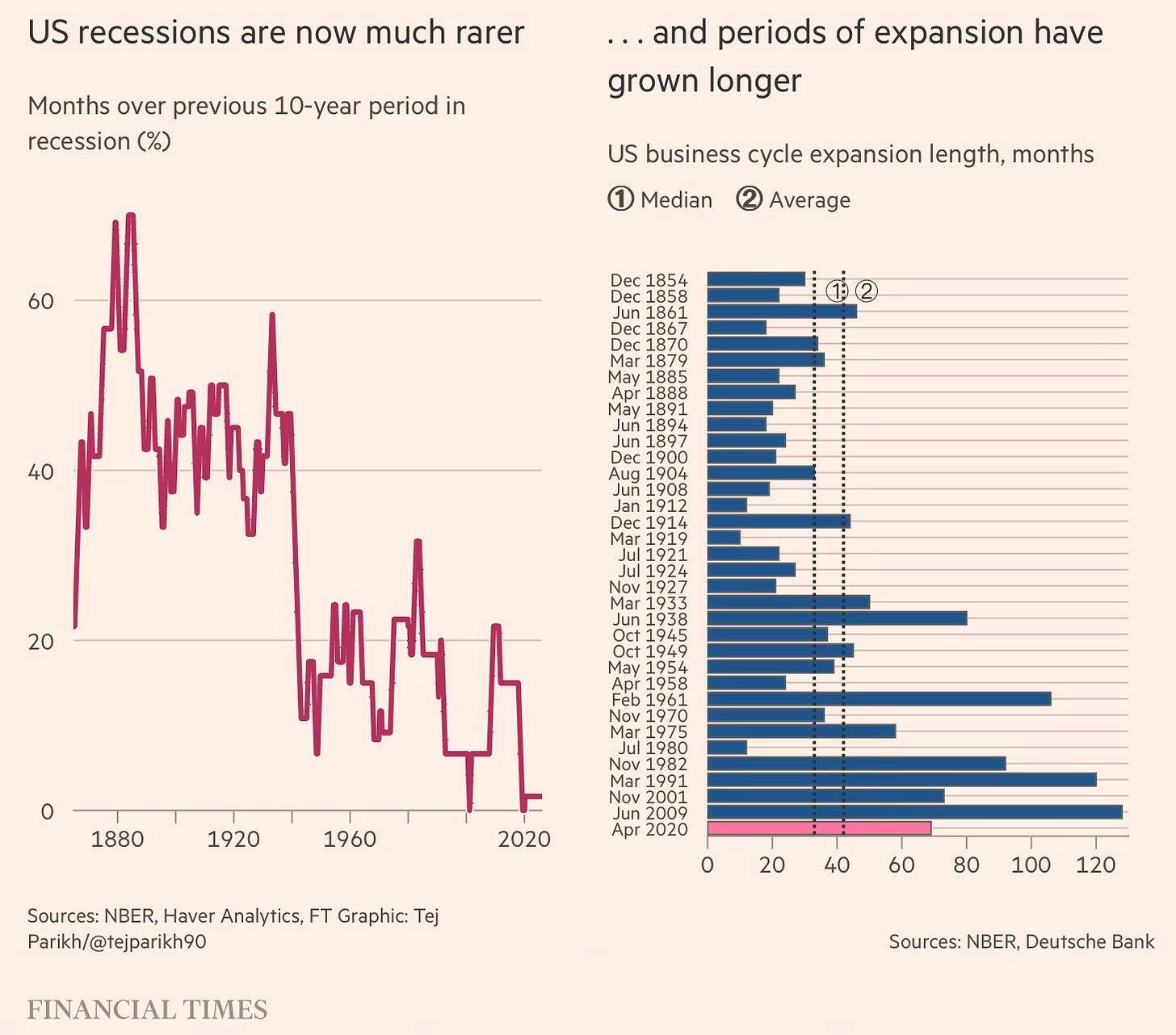

Sample these statistics about the trends with US recessions.

The US has only seen four recessions since 1982. But over the previous 40 years there were nine, and over the 40 years before that there were 10… The US economy was in recession for 58 months over the past five decades compared to 143 in the equivalent period prior, based on data beginning in the 1850s from the National Bureau of Economic Research… The past five cycles of US economic expansion — including the current one that began in the aftermath of the Covid-19 lockdowns — have averaged more than eight years, which is close to triple the average length of cycles before.

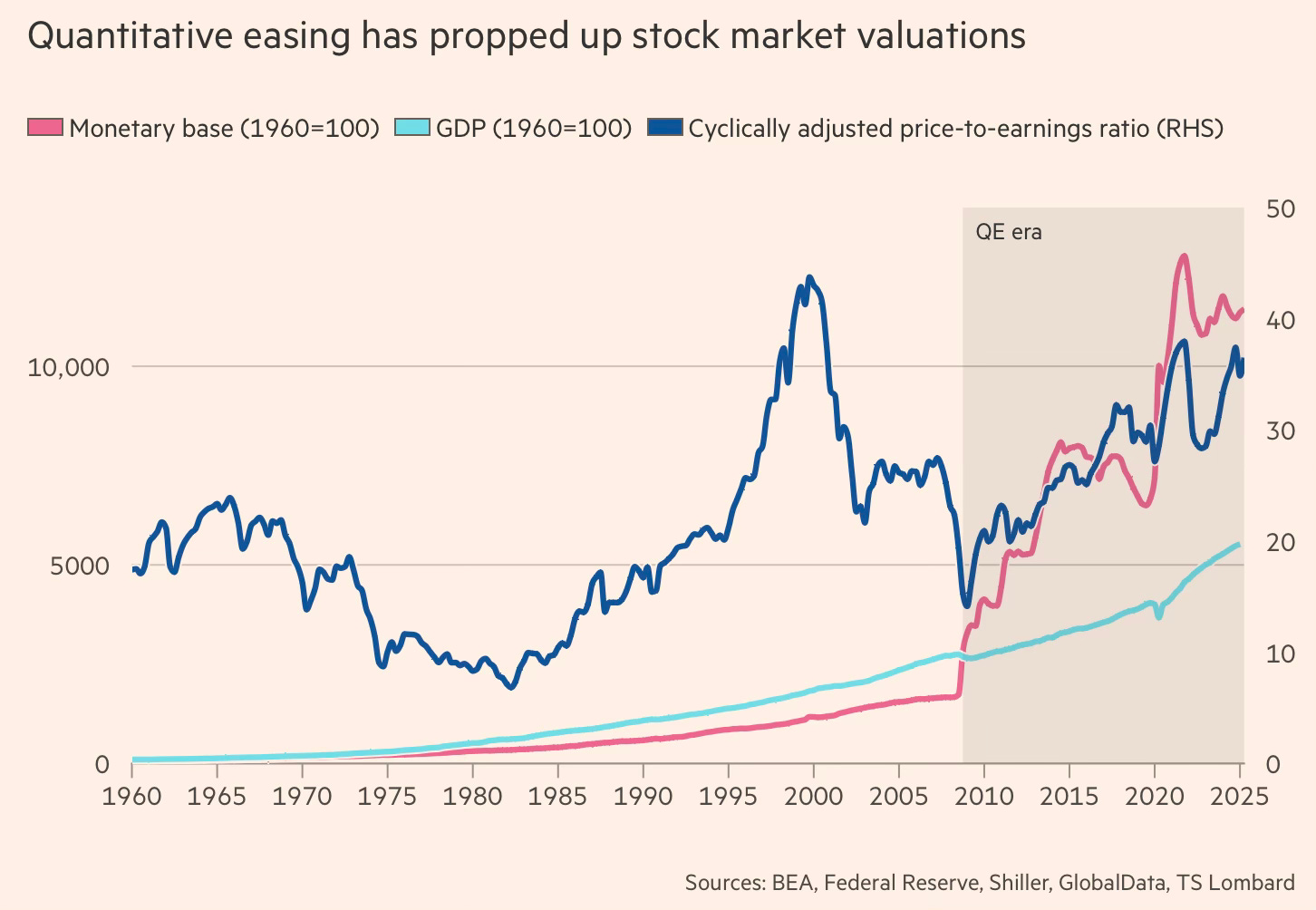

Thanks to quantitative easing, the US monetary base has expanded dramatically since the GFC, and equity market valuations have continuously soared.

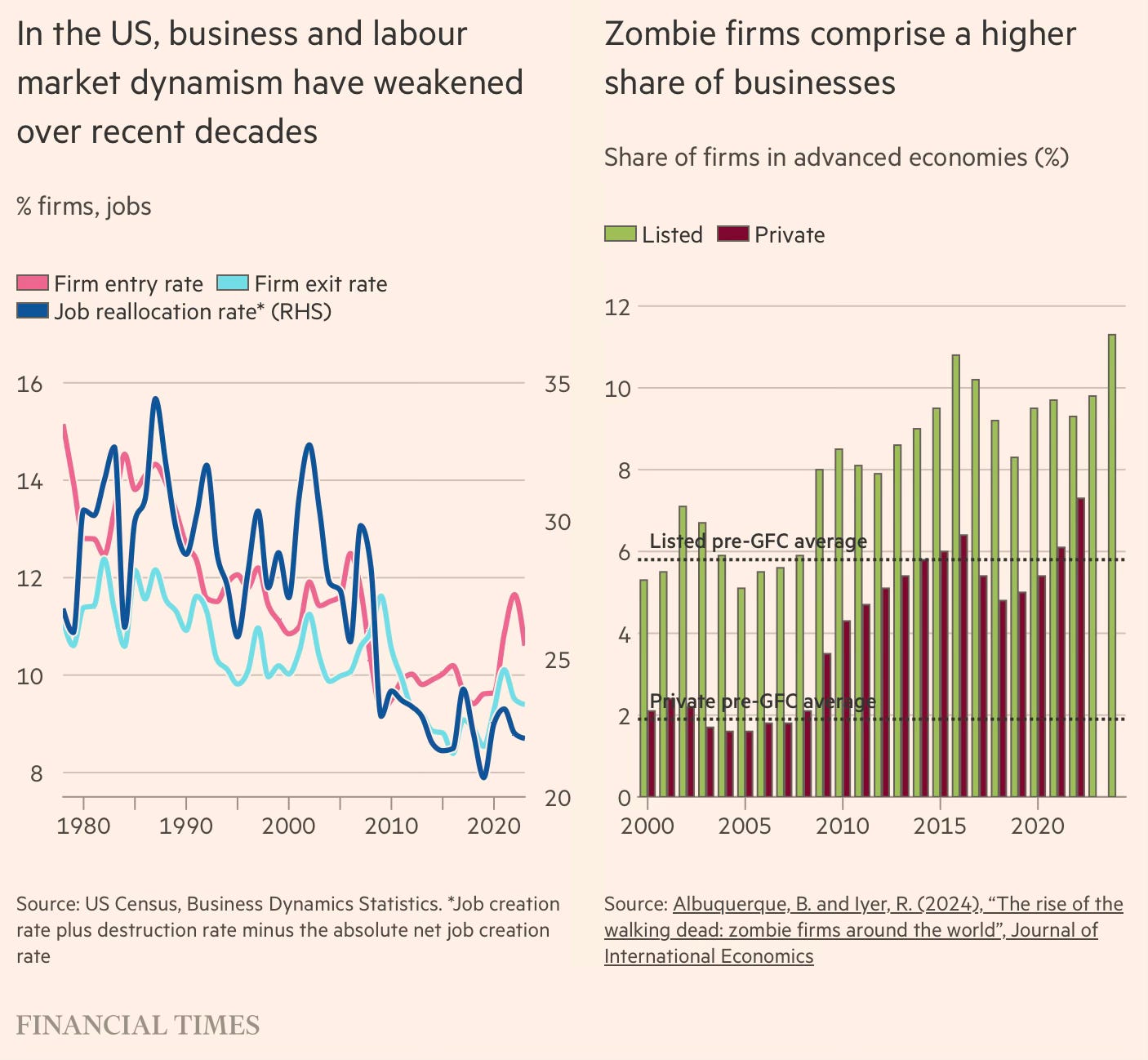

The extended period of cheap money has distorted incentives by misallocating resources, keeping capital and people locked up in less productive parts of the economy, keeping alive zombie firms and funds, and weakening economic dynamism.

See also this graphical feature from Parikh on how economic dynamism is impeded by “statism, easy money, and risk aversion”.

It is useful here to step back and reflect on the role played by economic thinking. Economics has doubtless contributed to a better understanding of macroeconomic issues and the formulation of policies to address problems. In fact, it has played an important role in shaping the extraordinary period of human development and economic prosperity since the War.

However, economic thinking has also resulted in many undesirable trends and distortions. Arguably, the most important trend of relevance to our times is the regime shift in monetary policy from one that sought to control inflation to one that balances inflation control with backstopping the financial markets and economic growth.

While this regime shift in monetary policy is associated with the global financial crisis (GFC), it may have had its origins in the Greenspan put that emerged in the aftermath of the 1987 stockmarket crash. Since then, through a series of instruments, the scope and breadth of monetary policy actions have expanded continuously. It has been the big triumph of technocracy in economic policymaking.

Interest rate changes have come to be supplemented with central bank balance sheet expansion through liquidity injection windows, quantitative easing, macroprudential measures, yield control actions aimed at long-term sovereign bond rates, direct purchases of corporate bonds, and forward guidance actions.

What started as measures to ensure financial stability has now morphed into an institutionalised set of tools to backstop financial market declines, and thereby economic growth itself. There has been a wholesale reshaping of expectations among a generation of investors and market participants. This has resulted in a sharp erosion of the disciplining powers of the financial markets in capital allocation.

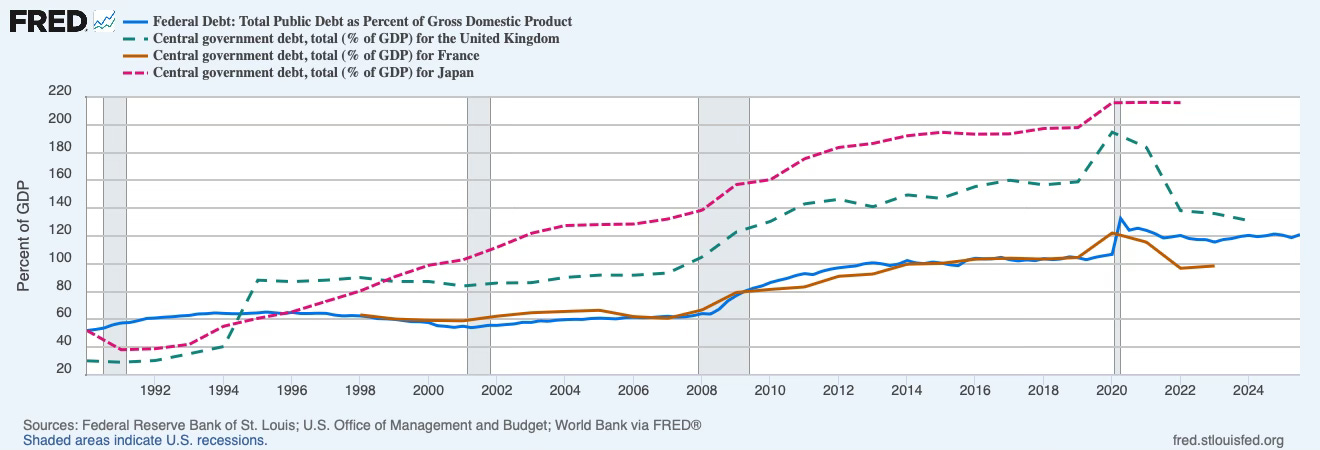

Economic thinking has emboldened governments on fiscal policy, too. The result has been the dramatic fiscal expansion, especially but not only since the GFC, as governments have run persistent large fiscal deficits to sustain economic growth. The US public debt to GDP ratio has nearly doubled since 2008.

Worryingly, these actions have engendered perverse incentives among politicians and policymakers. A generation has come to believe that fiscal and monetary policy offers an unlimited arsenal of options to stabilise equity markets and prevent recessions. The ideological cover provided by economists, coupled with the rising applications of these tools with little apparent costs, has emboldened them.

This is most evocatively captured in the unqualified “whatever it takes” assurance given by Mario Draghi, the President of the European Central Bank, at the height of the Eurozone crisis in 2012. It was followed up by the ECB in the 2012-15 period with its ‘Big Bazooka’ measures involving aggressive QE, liquidity windows, and reduction of rates to negative territory. He was merely following in the footsteps of Ben Bernanke during the GFC, and was followed subsequently by Jerome Powell during the pandemic meltdown.

Donald Trump’s arguments for lower rates must be seen against this backdrop. As a democratically elected leader, he is making a legitimate political choice of wanting to sustain high economic growth rates and continue the equity market boom. Further, never mind its consequences, he’s probably right in arguing that lower rates can help both political objectives, even if only for some time. Alan Greenspan, Ben Bernanke, Janet Yellen, Jerome Powell, and Mario Draghi made similar choices, especially in continuing monetary expansion far beyond what was required, to much acclaim and little pushback. Their decisions were accepted as technically correct choices. Donald Trump cannot be faulted for being upset at the apparent hypocrisy.

The political pressures to keep rates low are supplemented by the emerging high stakes of the big technology firms leading the AI charge. The two have become intertwined, also because of the outsized role of the surging AI investments in economic growth in the US. Nobody wants monetary policy to rock the boat in these euphoric times of impending transformative change.

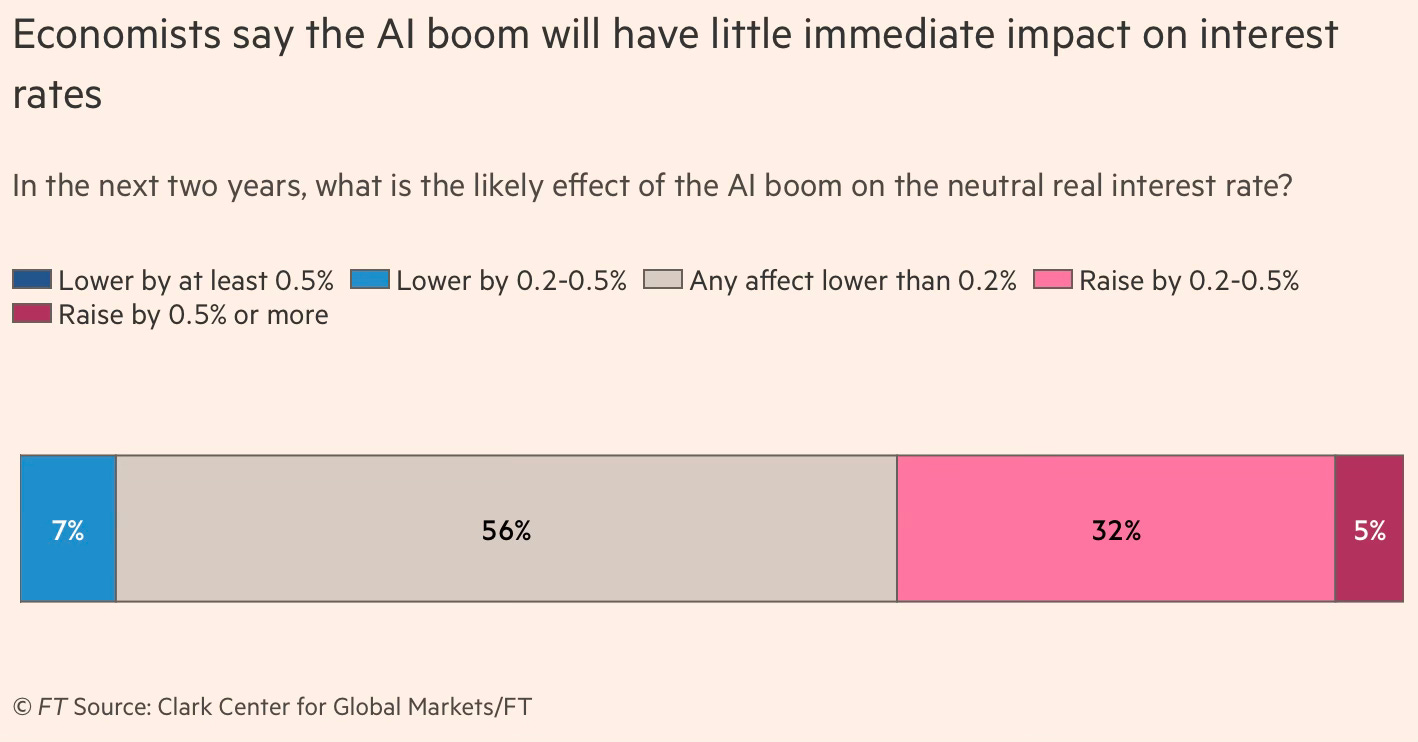

It is therefore unsurprising that Kevin Warsh, the incoming Chairman of the US Federal Reserve, has already indicated his bias towards monetary accommodation, arguing that the productivity boom likely from AI adoption will create the space for interest rate cuts. Warsh has claimed that AI will trigger “the most productivity-enhancing wave of our lifetimes — past, present and future”. Never mind that his fellow economists think otherwise, and argue that it could raise demand and price pressures, at least in the short-term.

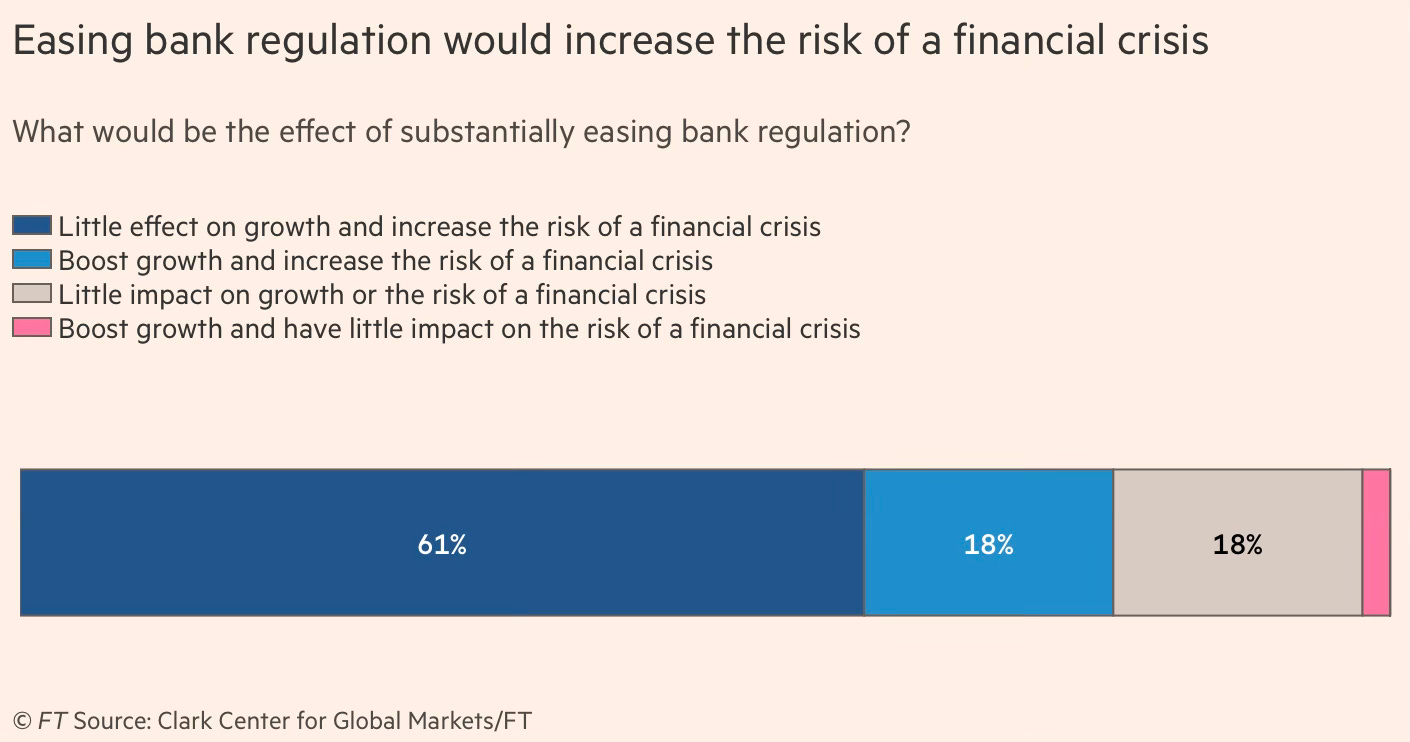

Interestingly, Warsh also argues in favour of easing bank regulation, another policy favoured by President Trump, whereas his colleague economists feel that it would increase the risk of a financial crisis.

John Maynard Keynes famously said, “Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influences, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist.” It is equally likely that “defunct economists” are the slaves of “practical men” of the political variety. Kevin Warsh appears to be a likely candidate.

A problem with economic arguments is that the discipline allows one to make conflicting arguments grounded in theory. It is not surprising that a frustrated Harry Truman famously demanded a one-handed economist. Sample this on the likely impact of the AI-boom highlighted by Robert Barbera of Johns Hopkins University.

“The AI boom may generate a booming economy, shrinking budget deficits, higher neutral interest rates and comfortable shrinkage of the Fed’s balance sheet. Or we may experience a financial market crack-up, a deep recession, a dramatic rise for deficits, eliciting a return to zero short rates, a swoon for the dollar, and demands for another big dose of [balance sheet expansion].”

Jason Furman writes about the complicated nature of the relationship between productivity and inflation.

Over the long run, productivity growth does not determine inflation. Productivity reflects the economy’s real productive capacity; inflation reflects monetary policy choices. But sustained faster productivity growth does raise the economy’s neutral real interest rate. To prevent inflation, central banks must therefore maintain higher nominal rates. The mechanism is straightforward. Faster productivity growth allows households to save less because they anticipate higher future income, while prompting businesses to invest more because expected returns rise. Both of these boost demand and push up real interest rates. In the short run, an unexpected acceleration in productivity can influence inflation, but the direction is ambiguous.

Greenspan’s hypothesis was that higher productivity allowed nominal demand to grow faster without igniting inflation. Because wages adjust less frequently than prices, this initially showed up as slower price growth rather than faster wage growth. That dynamic may well have characterised the early years after productivity began accelerating in the mid-1990s. But there is a competing short-run effect that runs in the opposite direction. Anticipation of a sustained productivity boom can itself be inflationary, by lifting equity prices and household spending and by spurring business investment. At bottom, this is a timing race: does demand surge ahead of supply, or does supply expand fast enough to accommodate demand without inflation? In the late 1990s — just as today — there was no clear way to know in advance which would dominate.

Another Warsh preference is likely to be to steepen the yield curve by lowering short-term rates through lowering repo rates and raising long-term rates by winding back the Fed’s balance sheet. Martin Sandbu describes how the same set of policies can have contrasting effects.

It is not at all clear whether a steeper yield curve will by itself amount to a looser or tighter overall monetary policy stance. That depends on the relative moves at the different maturities, and how strongly they affect the economy — through exchange rate movements, market valuations and government borrowing costs at the short end, and through “real economy” financing costs such as mortgage rates at the long end. Warsh himself has intimated that the long benchmark Treasury rates are more consequential than short-term policy rates. I share this view. But it is clear that short-term rates matter a lot too. So the macroeconomic effects of a yield curve steepening go in both directions and it’s hard to be confident of the overall impact.

The larger point here is that in the US (and maybe elsewhere), the political acceptability of even small shocks has diminished significantly; economists have come to embrace hitherto unorthodox fiscal and monetary policy measures; and equity markets have become very high-stakes bets. The consequence of these trends is the postponement of smaller recessions and the accumulation of vulnerabilities that increase the risk of bigger recessions.

No comments:

Post a Comment