Business Standard points to a paradox in India’s medical education - post-graduate seats lying vacant amidst a shortage of specialist doctors.

It points to data from the Health Dynamics of India report by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare.

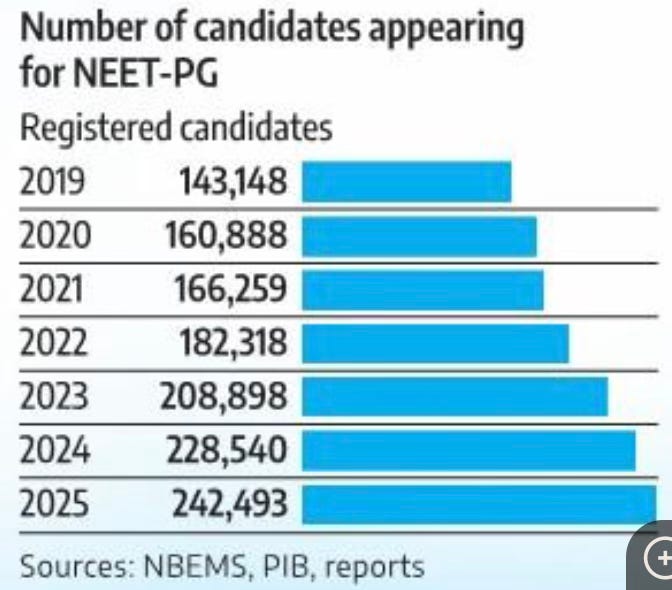

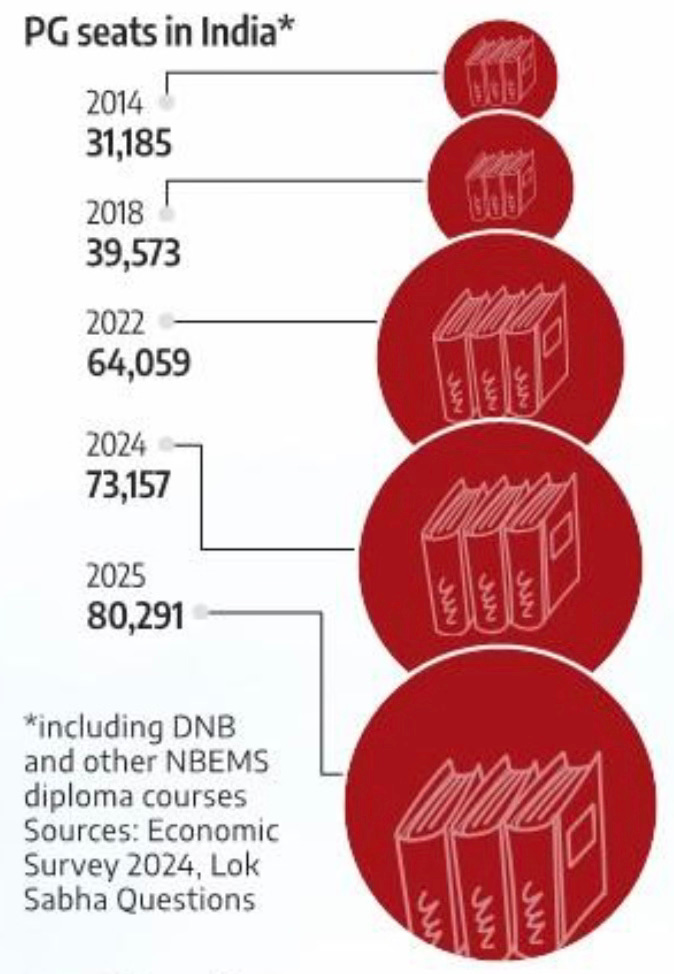

Community health centres (CHCs) in rural India face an almost 80 per cent shortfall in specialists. As of March 2023, just 4,413 specialist doctors were available against a requirement of 21,964 across 5,491 CHCs in 757 districts, each centre serving an average population of nearly 160,000 per centre… The number of PG medical seats for MD and Diplomate of National Board (DNB) courses rose 157 per cent to 80,291 in 2025 from 31,185 in 2014, with the government planning to add another 2,000-3,000 seats by 2029… India generates over 123,000 MBBS graduates per year…

As a result, filling the seats on offer remains a challenge. After two full rounds of NEET-PG 2025, over 18,000 seats remained vacant, forcing the National Board of Examinations in Medical Sciences (NBEMS) to keep slashing qualifying cut-offs… candidates with zero percentile scores became eligible for counselling in further rounds… Zero percentile means candidates who scored the lowest in a test, or that none of the other candidates scored less. Such relaxations have become routine. Cut-offs were reduced to zero percentile in 2023, 2024 and, earlier, throughout the Covid years… Vacancies are most pronounced in private and deemed universities, which account for nearly 10,000 unfilled seats annually…

Specialities such as cardiology, radiology, gynaecology, orthopaedics, and general surgery traditionally being the most sought after. On the other hand, seats in non-clinical subjects such as pathology, anatomy and biochemistry have vacancy rates of 50-70 per cent, as many candidates prefer to drop a year rather than opt for these disciplines. However, doctors say even traditionally sought-after clinical specialities are now seeing gaps.

The article posits several explanations for the paradox, including high fees, poor quality in private colleges, mandatory service bonds, regional imbalances in seat distribution (half the seats being in the South), declining attractiveness due to safety and other concerns, lack of commensurate increase in MBBS seats, and so on.

Instead, I am inclined to argue that these are all symptoms of more basic problems. While there is no specific evidence, I feel that this highlights two first-order problems on both the demand and supply sides.

On the demand side, the vacancies reflect the poor quality of education in general and basic medical education in particular. What does it say about the quality of the MBBS education when nearly 2.5 lakh students could fill only 62,000 out of the 80,000 PG seats after two rounds of counselling, even at cutoff scores of 235-276 out of 800?

On the supply side, the sharp 2.6-fold increase in PG seats over a decade appears to have compromised quality. Does India’s medical education ecosystem have sufficient supply of good-quality teaching personnel (human capital) and well-equipped hospitals to adequately train the 2.6X increase in PG seats? I’m not sure.

This is the point made on multiple occasions in this blog about India’s problems of poor quality of human resources and the low capital base of supply across sectors that constrain sustained high economic growth. Fundamentally, high economic growth can be sustained only if there’s a broad enough capital base (physical, human, industrial, financial, and institutional) to support that growth.

This is also central to the larger point about high economic growth rates requiring the foundations of a broad base of human development and economic growth.

No comments:

Post a Comment