Much has been written about the fiasco with Indigo Airlines early this month. The crisis was triggered by the airline’s inability to mobilise eligible pilots to comply with the Flight Duty Time Limitation (FDTL) rules that came into effect from November 1, despite nearly two years of preparation time.

The Directorate General of Civil Aviation (DGCA) announced the rules in January 2024 that included capping duty time at 100 hours, an increase in weekly rest from 36 to 48 hours, limits on the number of night flights pilots can operate, restricting night landings to two a week (from six earlier), and no more than two consecutive night duties a week.

Over nearly two decades, Indigo had established itself as the country’s pre-eminent airline and a globally renowned brand, with a 65% domestic market share and operating 2200 flights daily. The fiasco has shattered that reputation.

This post will highlight a few lessons from the Indigo crisis.

1. Efficiency maximisation comes at the cost of resilience. Indigo’s efficient operational performance, its USP, appears to have been achieved by focusing on the short-term concerns.

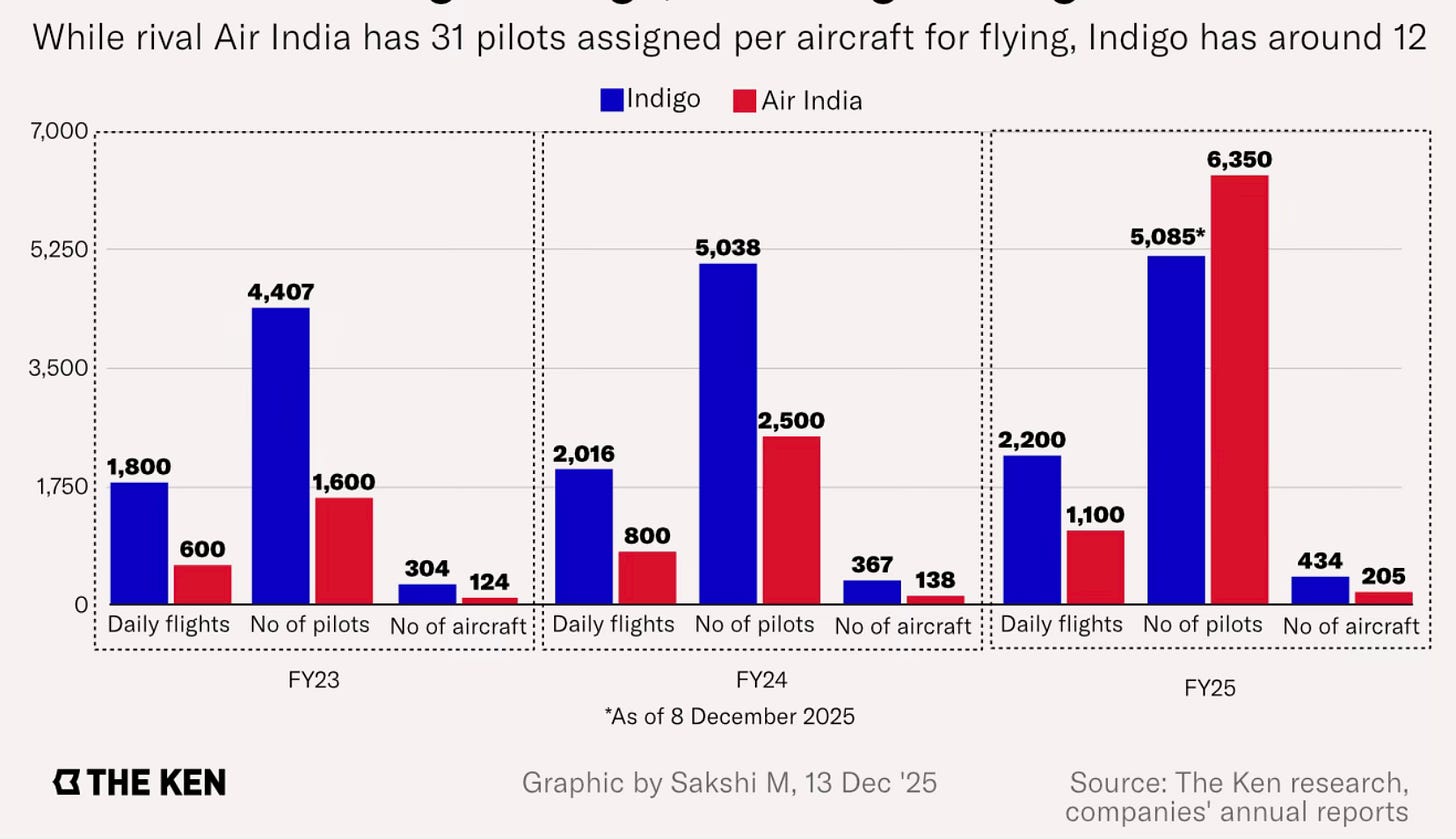

At the heart of the problem is the availability of pilots. Interestingly, despite its 65% market share, IndiGo had just 5085 pilots compared to 6350 for Air India with a 25% market share. Further, while Air India had 31 pilots per plane, Indigo had just 12.

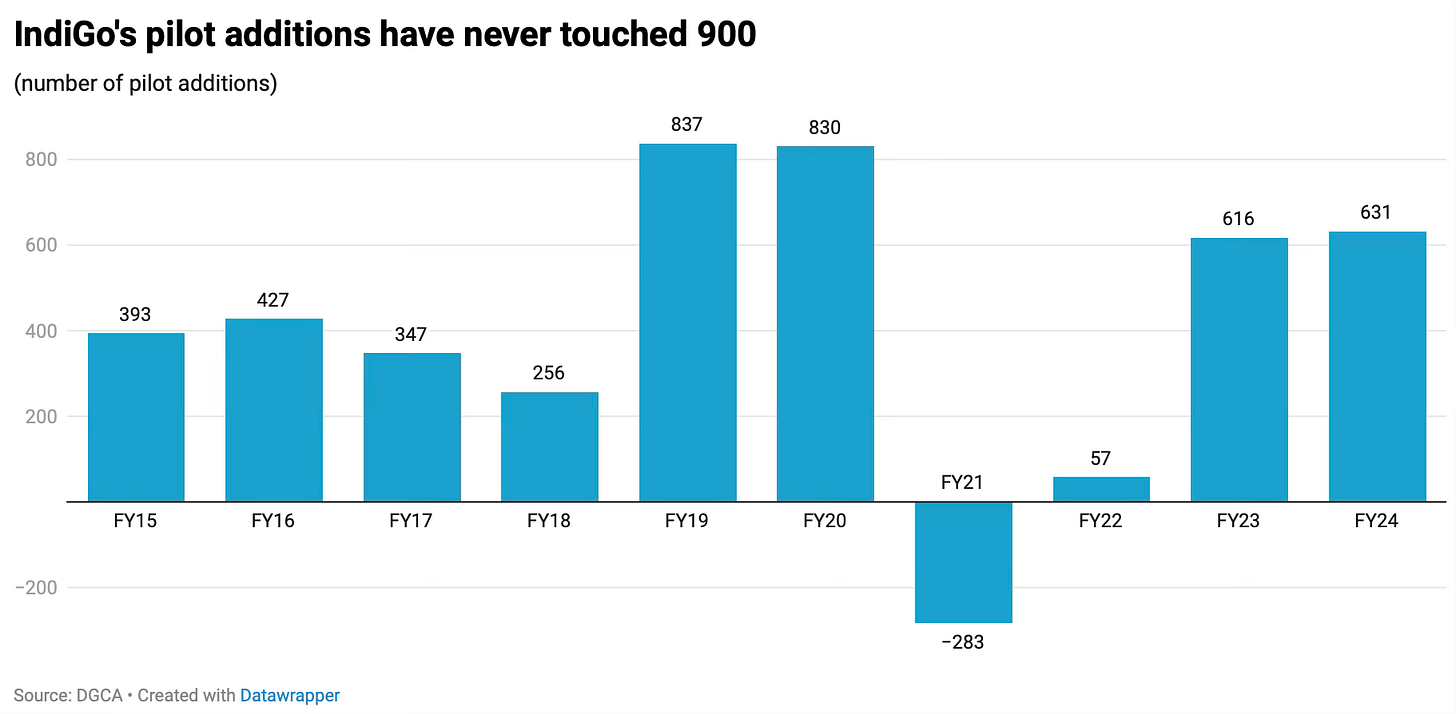

In fact, despite the advance information about FDTL, Indigo’s hiring of pilots remained far lower than required.

Further, the number of pilots actually declined 7% between March and December 2025. Interestingly, in the same period leading up to the FDTL rules coming into force, Air India’s pilot numbers nearly doubled from 3,280 to 6,350.

2. The disruptions in the aviation industry, caused by the Indigo flight cancellations, are yet another reminder of the problems with market concentration. Such market concentration exposes the sector to Too Big To Fail (TBTF) risks that, in turn, distort incentives across stakeholders. It erodes market discipline and encourages the dominant incumbents to dictate the market evolution.

The Ken article linked above highlights how its market dominance meant that it exercised disproportionate market power over the pilots and presided over a difficult work environment. Further, as has been suggested by many, Indigo may even have thought that, given its market dominance and the possible market disruption, the DGCA would not be able to enforce the FDTL rules. The lack of urgency in hiring pilots by Indigo, as highlighted above, is another example of the distortion in incentives resulting from its market power.

Even after the FDTL rules were announced, it had to be postponed several times due to pressure from the dominant airlines. The repeated deferrals of the enforcement of the rules might even have emboldened the Indigo management. In this way, market concentration also blunts regulatory power.

It is therefore to the government’s credit that it did not back down when faced with the chaos. It also did the right thing by cutting Indigo’s flights by 10% till March 2026. This is an important signal to shape market expectations.

3. Sustained rapid growth can happen only on solid foundations. This applies as much to countries as to companies. In Indigo’s case, the fiasco has exposed that its apparent operational excellence may have been built on shaky corporate foundations. Genuine companies are built to last.

The acute scarcity of qualified pilots, so badly exposed here, should be a reminder to governments about the importance of the supply-side in sustaining high economic growth rates. The supply of pilots is constrained by the supply-side of prospective pilot aspirants with requisite qualifications, their affordability, flying schools, training and test facilities, licensing capabilities, and so on. There are hard limits to relaxing these constraints, even with the best of efforts.

The rapid expansion of the aviation market in India has now brutally exposed this problem. It is estimated that with over 1700 new aircraft orders and rapid fleet expansion plans, the domestic carriers would require nearly 30,000 new pilots in the next 15 years. But the DGCA issued only 1,213 commercial pilot licences in 2024, lower than the 1,622 licences issued in 2023 and only slightly above 1,165 in 2022.

There’s also a significant cost incurred by the airlines from such supply constraints. In tight labour markets, incremental hirings come at a steep cost.

While the airline employed 5,038 pilots at a cost of Rs 3,121 crore in FY24, the addition of 631 pilots over FY23 did not occur at the assumed Rs 62-lakh cost but at closer to Rs 1.3 crore per pilot. Even after adjusting for salary increases for existing pilots, IndiGo’s effective acquisition cost for new pilots in FY24 hovered around Rs 1 crore.

4. This is yet another reminder to those who proclaim the private sector and market efficiency mantra and oppose government regulation. Poor track record of regulation does not negate the need for regulation, nor does it mean a shift to a regime of deregulation. Instead, the endeavour should be to improve the capabilities for good regulation.

The FDTL rules impose an elaborate set of pilot duty standards requirements based on the global aviation industry. These standards may appear too prescriptive for those who swear by market efficiency and deregulation. But, given the importance of safety in this industry, ensuring pilots get adequate rest through such prescriptive regulations is an example of where regulatory standards are desirable.

The aviation industry is a good example of an industry where deeply prescriptive regulations on several aspects have ensured spectacular success in safety. It underlines the point that it is not the regulations by themselves that are bad, but the challenge is to integrate them into industry practices. In other words, regulation should become incentive-compatible for the industry and therefore be owned by the industry. This aspect of regulation often gets missed in the debates on deregulation.

5. Arguably, the biggest takeaway from the Indigo fiasco should be about the perils of market concentration. A market like India, with massive growth potential, should have at least four or five airlines, and none with more than a third share. This applies as much to several other infrastructure sectors as to the airline industry.

It raises the question of why is it that a country with such market growth potential should have a paucity of entrepreneurs in these sectors, as to have just the same one or two firms dominating so many sectors?

India’s power generation, airport, and port privatisation were true successes of PPP globally. They led to the emergence of a generation of infrastructure entrepreneurs that promised an era of competitive markets and with the potential to lead the growth of these sectors. However, most of them have fallen by the wayside, often being forced to give up control in some form or other. The market in these sectors today has come to be dominated by the same few groups.

This trajectory of market evolution in sectors like ports, airports, and others, like the cement industry, shapes expectations and deters entrepreneurs and investors from risking their capital in the long-term growth story of the country. This does not bode well.

6. Finally, this fiasco also underscores the importance of state capability in managing market development. Robust markets, especially in these sectors, require proficient regulatory engagement. Failure to enforce violations and penalise the offenders creates a moral hazard that weakens regulatory deterrence.

It also does not help that the DGCA is chronically understaffed compared to its peers elsewhere, and nearly half the posts are vacant (801 out of 1630). The same is the case with the other entities in the sector, BCAS and AAI.

No comments:

Post a Comment