As the year draws to a close, the Government of India has unveiled a series of reforms - deregulation, GST rate rationalisation, Labour Code implementation, removal of limits on FDI in insurance, allowing private investment in nuclear power, etc.

In this context, some observations on the India economy as we move into the new year.

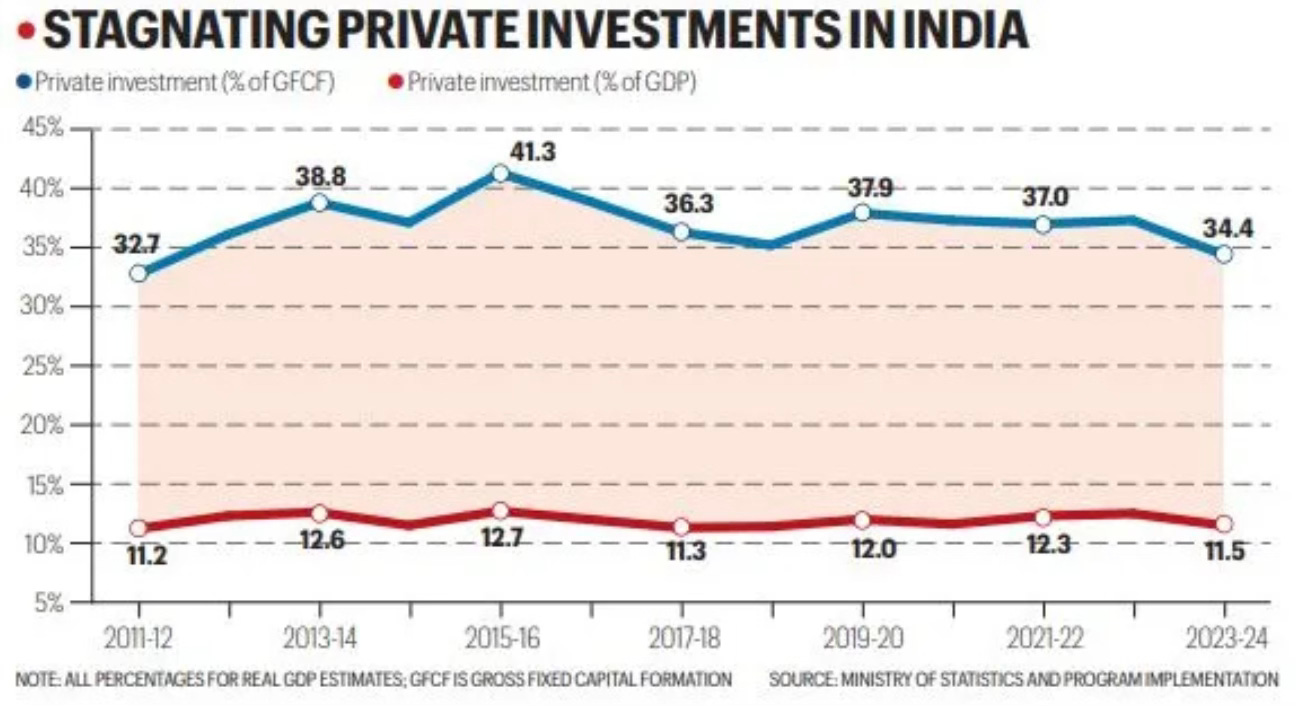

1. Arguably, the biggest concern with the Indian economy, and that too for a long time, has been private investment. It has been the dog that has not barked. And it has been the case since the Global Financial Crisis.

Even as public investments have surged, especially since the pandemic, private investments have remained stuck in the 11-12% range for the last 15 years and have declined as a share of the gross fixed capital formation, which itself has declined.

Even the corporate tax cut of September 2019 has failed to stimulate private investment. Companies appear to have used the rise in cash reserves to pay off debts. As the Indian Express report points out, the “interest coverage ratio of more than 3,000 companies — excluding those from the financial sector — has more than doubled to 5.97 in the first half of 2025-26 from 2.6 in the same period of 2020-21”.

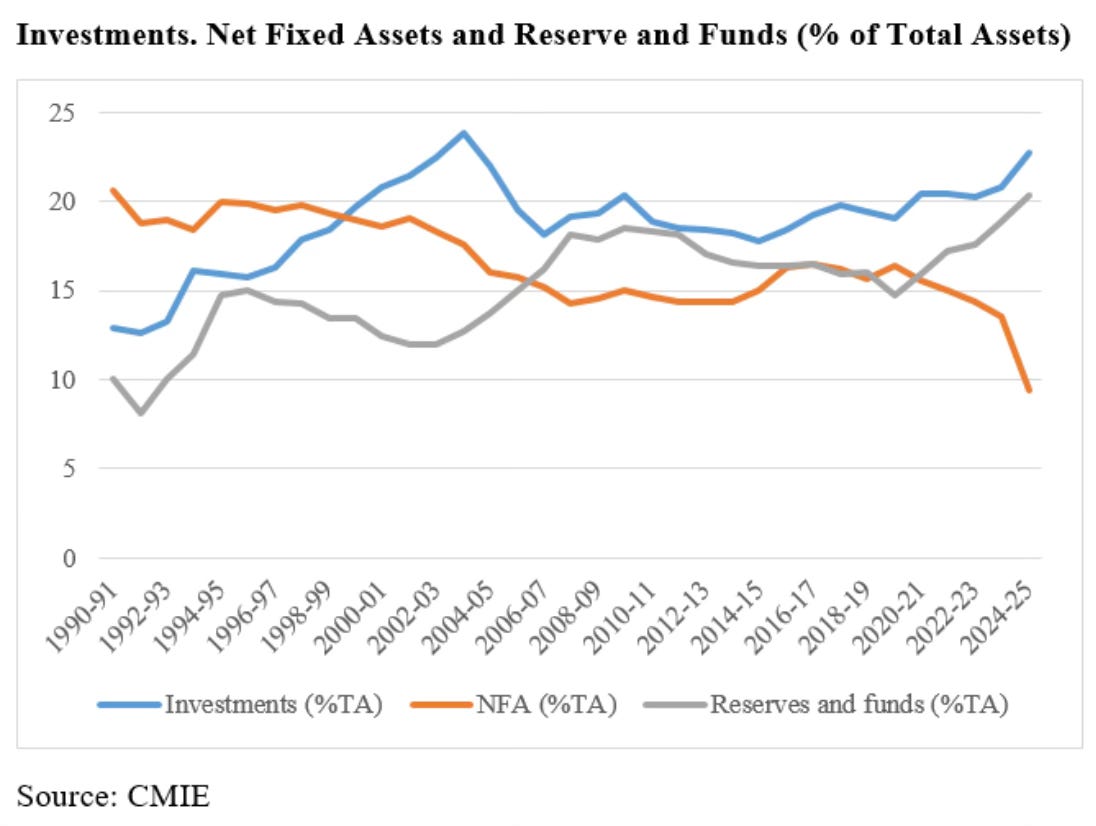

Further, as an NIPFP blog shows, far from raising investment, the post-pandemic period is associated with declining fixed assets as a share of total assets and rising financial assets.

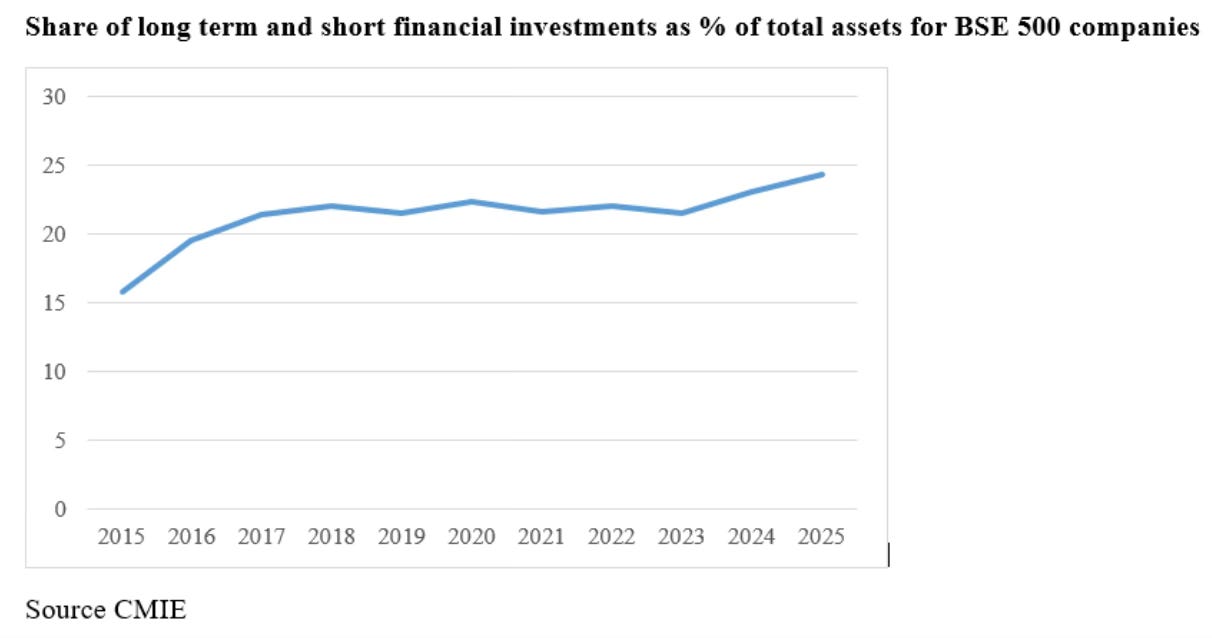

The NIPFP blog also finds a distinct rise in the share of long-term and short-term financial investments of the BSE 500 companies. In 2025, nearly a quarter of the assets of these companies were financial investments, a rise from just over 15% in 2015.

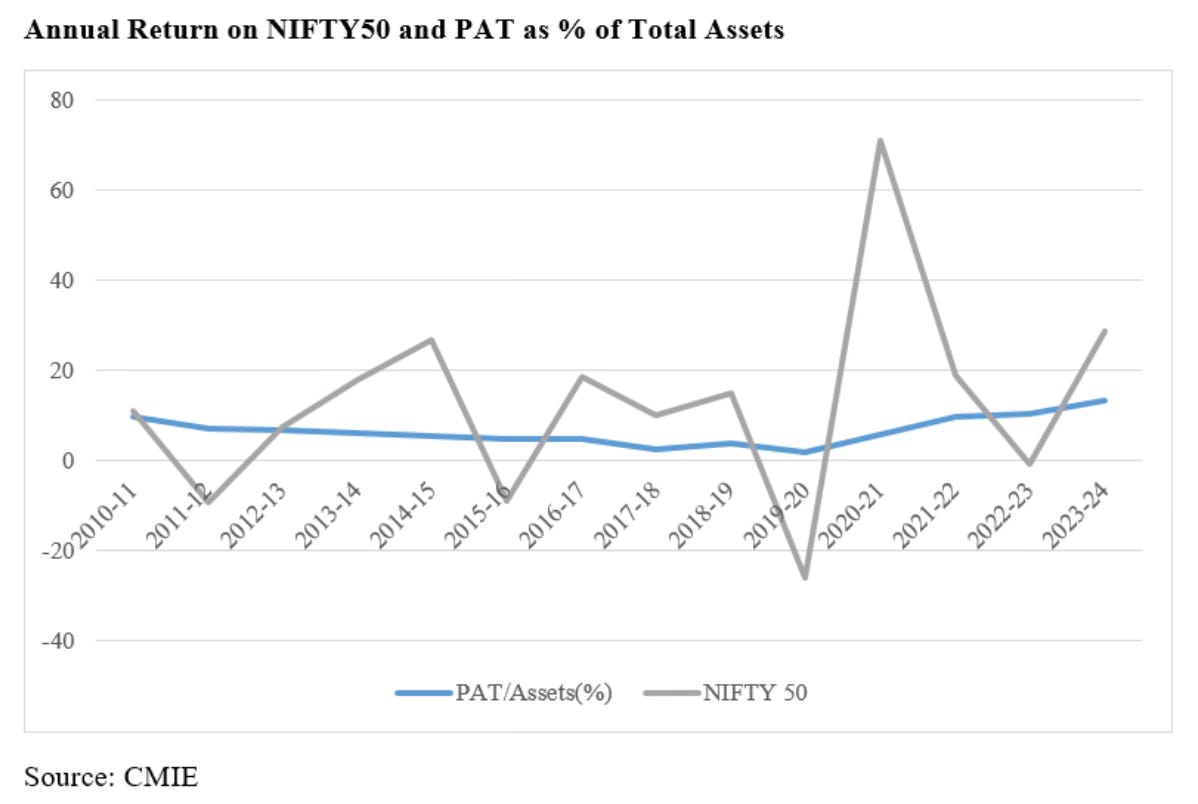

This misallocation towards financial assets is also partially driven by the attractive returns generated by the capital markets. The graphic below shows that the NIFTY 50 has outperformed corporate returns in most years since 2010-11.

2. Ultimately, private investment is driven by expectations about aggregate demand. The tepid aggregate demand has been a major problem with India’s economic growth model. While the country has grown at a rapid clip for most of the last quarter-century, it has not translated into broad-based gains across population groups, an essential requirement for sustaining high growth rates (instead of the episodic high growth periods that have been a feature of India’s post-liberalisation growth). I have blogged here, here and here in greater detail.

This may well be the main explanation for the stagnation in private investment. Attesting to this, as per the RBI’s Obicus Survey, capacity utilisation in manufacturing has crossed 75% of capacity (the threshold thought to be required to get firms to invest) only in 10 of the 53 quarters since the start of 2012-13. Adding to the reluctance of corporates, their profitability has been on a sharply declining trend.

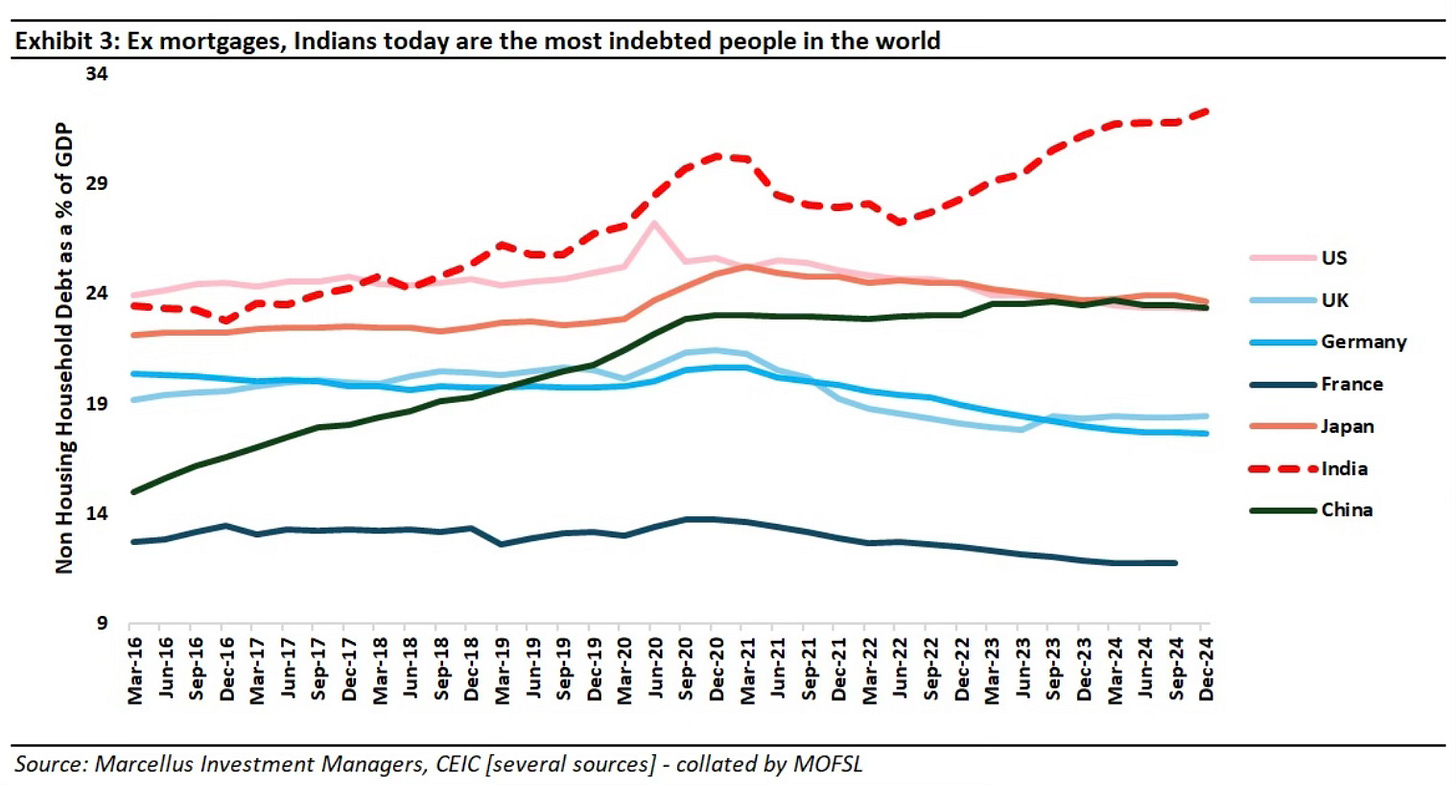

On the household side, since 2017, indebtedness, excluding mortgages, has been on a rising trend, increasing by about 40%. This is certain to have exercised a drag on consumption.

This trend also coincides with household savings dipping to a 50-year low of 5.3% of GDP in 2023-24.

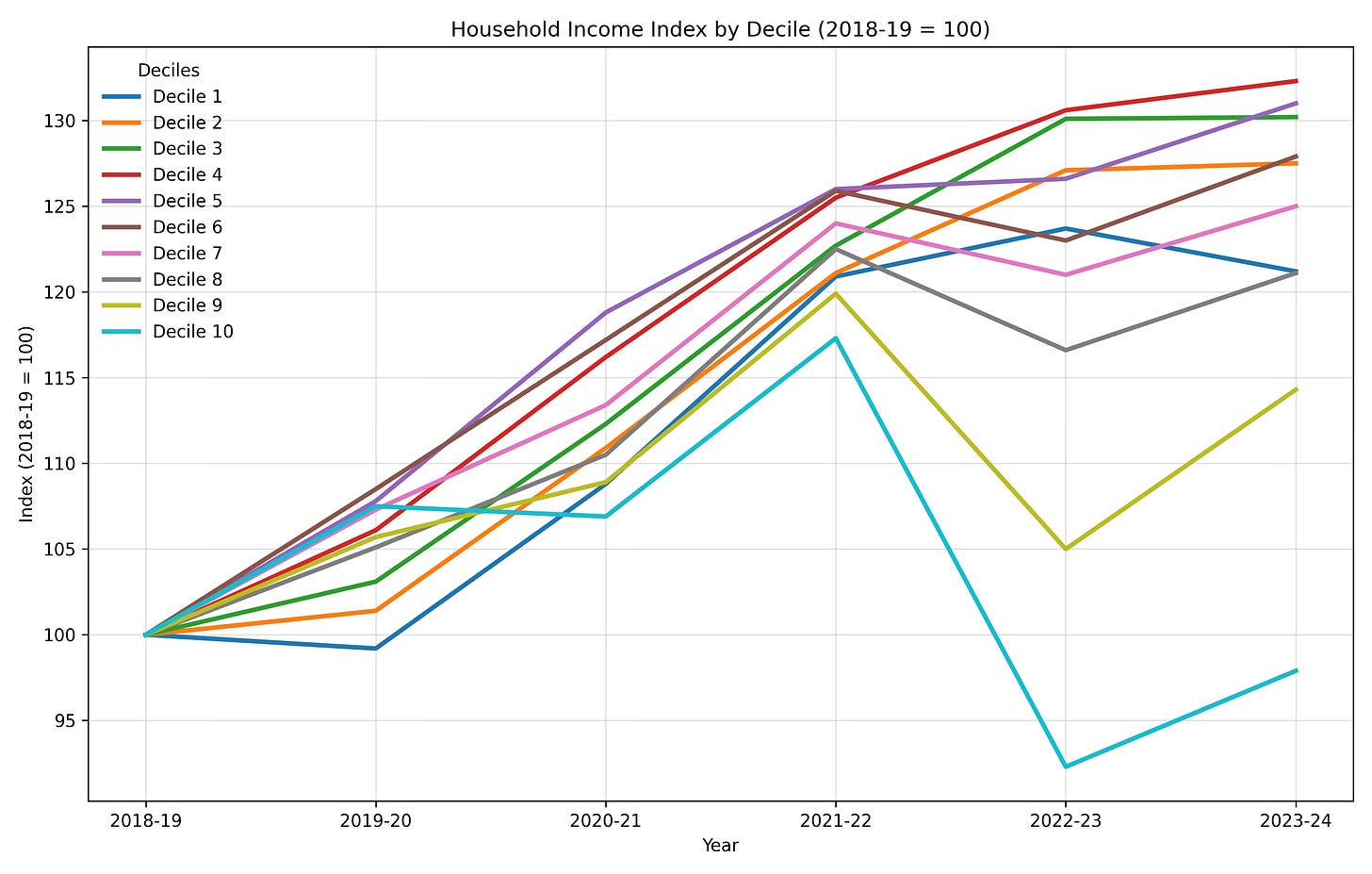

I used PLFS data from here and ChatGPT to generate the household income index by income decile for the 2018-19 to 2023-24 period. Note the K-shaped trend post-pandemic.

It shows that the D3 to D5 deciles grew the fastest, with the bottom three deciles being the weakest (the lowest decile declining).

A blog at Marcellus Investment Managers points to three back-to-back stimulus measures unveiled by the government to boost consumption - the income tax relief in the Union Budget of February 2025 by raising the tax slabs (Rs 1 trillion stimulus), the RBI’s five repo reductions (reduced interest outgo by Rs 2 trillion), and the GST 2.0 (Rs 2 trillion stimulus). The combined effect of the total of Rs 5 trillion amounts annually to about 1.7% of GDP, and its impact remains to be seen.

3. In any case, for all its big population size, the consumption potential of the Indian economy is woefully limited. This nicely sums up the challenge of making money in the country.

While India’s population of 1.4bn offers enviable scale, its market has proven difficult to monetise. According to Sensor Tower, Indian internet users downloaded 24.3bn apps in 2024 Andy spent 1.13tn hours on them, but total spending was just $1bn.

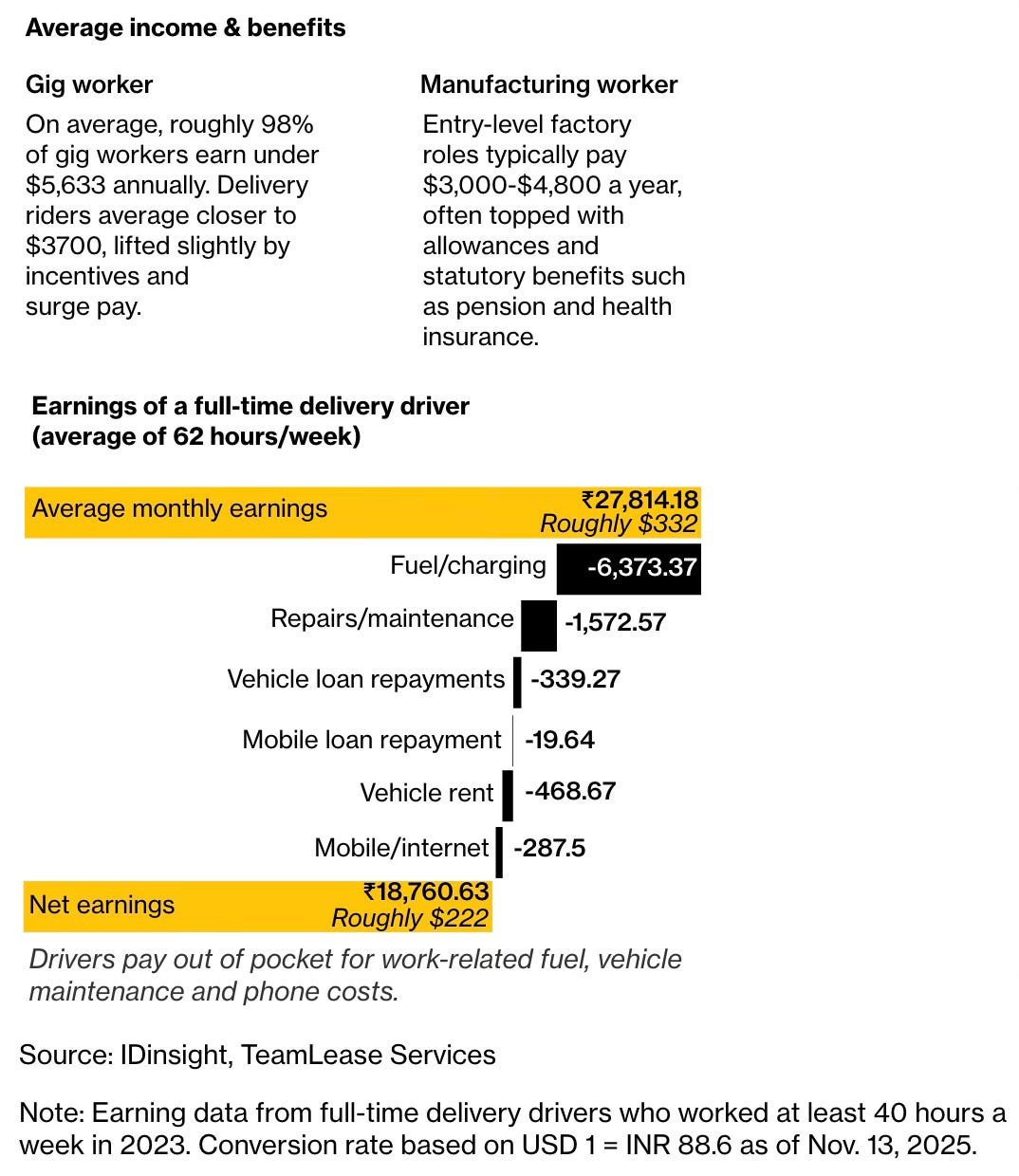

This highlights the importance of well-paying jobs in creating a large enough consumption class. Unfortunately, the gig economy, the largest creator of jobs, may not suffice in this regard, though it has its value in absorbing the large pool of workforce entrants.

4. In fact, it’s a possibility that the gig economy may actually be displacing more productive jobs. Bloomberg has an excellent article that captures a big labour market paradox, attracting workers to the factory floor amidst an acute shortage of good jobs and high youth unemployment. Surveys indicate India’s manufacturing sector faces a skills gap of 10%–20% across major functions, and around 75%–80% of employers report difficulty recruiting qualified talent.

But when you can easily get the same Rs 15000-18000 per month at your convenience with gig work like delivery riders (the gig sector employment is growing at 13% annually), why would you want to do the regimented hard grind of factory floor jobs? As the Bloomberg article writes,

Even as the world’s fastest-growing major economy bets on manufacturing to fuel its rise, the factory floor is no longer where many young Indians see their future. India’s biggest economic challenge isn’t choosing between factory floors and delivery apps — it’s proving it can grow both. Manufacturing drives exports and global clout; gig work brings opportunity to a nation struggling with the highestyouth unemployment in Asia.

Tiruchirappalli offers a vivid case study of this dilemma… more than 15,000 industrial units line the highways around the city, from fabrication shops to distilleries. For decades, these plants relied on workers from nearby villages. But rising incomes and better education in southern India have changed aspirations: locals now favor jobs in larger cities, and manufacturing is widely seen as carrying less social standing. Labor rules are loosely enforced — nine-hour shifts often stretch to 11 or 12 hours with no overtime pay. Gig work, by contrast, rewards longer hours and offers flexibility: Drivers can work two hours one day or 12 the next. To delivery driver Mark Sebastian Raj, a motorbike, a smartphone, and the choice of where and when to work, feel more appealing than clocking in at a foundry… The challenge is whether India can scale up factories fast enough to compete with China while protecting gig workers — without regulating them so heavily that it erodes the very flexibility that makes such jobs appealing.

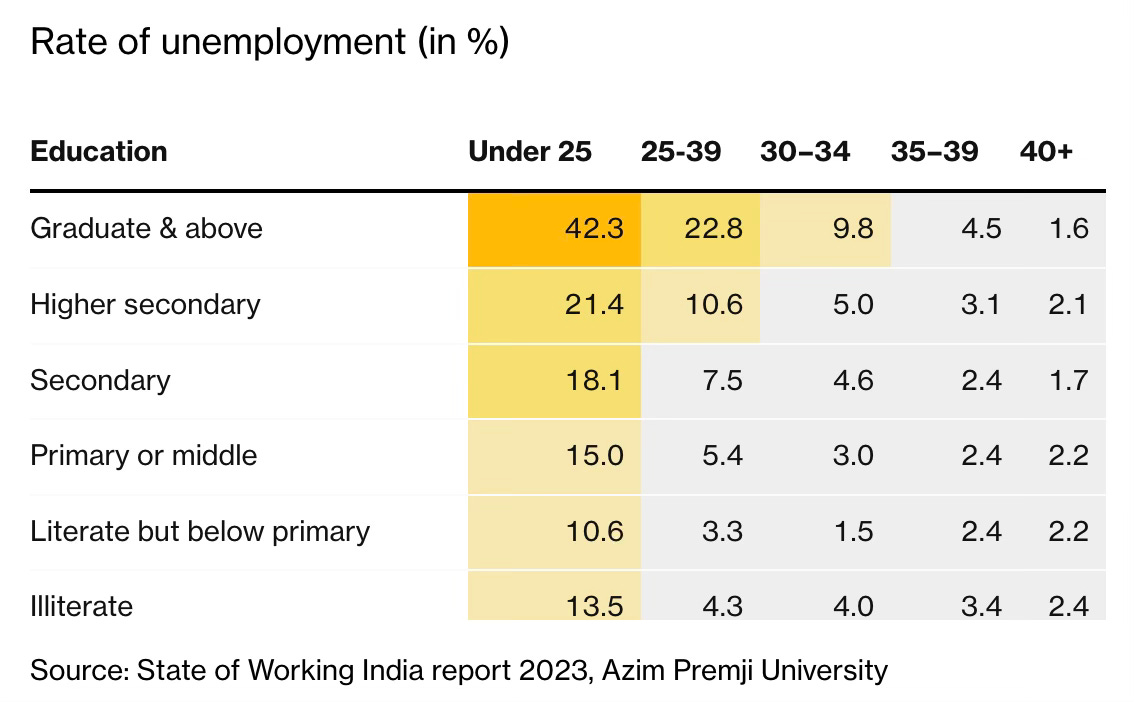

Reflecting the lack of good jobs amidst the surge in gig and contract jobs, a graduate in India is more likely to be unemployed than an illiterate youth.

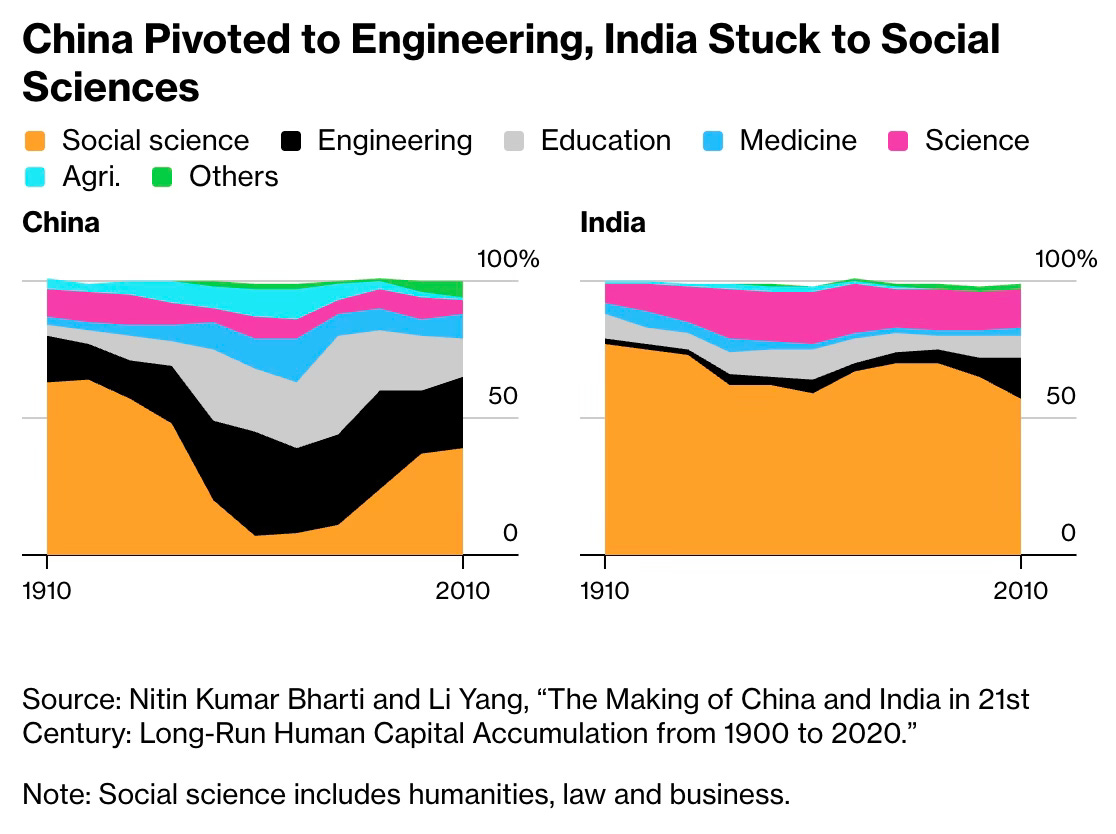

Tertiary education in India continues to remain excessively concentrated in liberal arts, in stark contrast to China.

5. India’s IT industry was a great opportunity for the country to leverage its head start and chart out a broad-based services sector-led economic growth model. Unfortunately, as I have blogged earlier, it has missed a succession of technology waves in the sector. And it has already fallen way behind on the AI-wave, too.

In fact, the IT sector may well be described as a good example of unproductive appropriation of corporate surpluses. While the IT industry generated large profits, which, instead of investing in R&D and emerging technologies, it chose to return to shareholders in the form of buybacks.

IT services still dominate with exports set to reach $210bn this financial year, India Ratings and Research forecasts. It has been a powerhouse industry for India but as IT services presented so much low lying fruit, the sector sucked up tech talent and capital from elsewhere. India’s SaaS sector in particular punched below its potential as a result. Software majors treated their services businesses as cash cows, deploying a small share to intellectual property assets. The 10 largest IT services companies had consolidated profits of $114bn in the past decade; 75 per cent of this was paid out via dividends and buybacks.

Their R&D expenditures are abysmally low.

The top five Indian IT firms had free cash flows of nearly $13bn in the 2023-24 financial year, according to HFS Research. And Infosys said on September 11 it had approved a $2bn share buyback offer — a week before the Trump order. Yet the R&D to sales ratio for India’s IT industry is abysmal: 0.88 per cent on average, according to a 2024 report by India’s Ministry of Corporate Affairs.

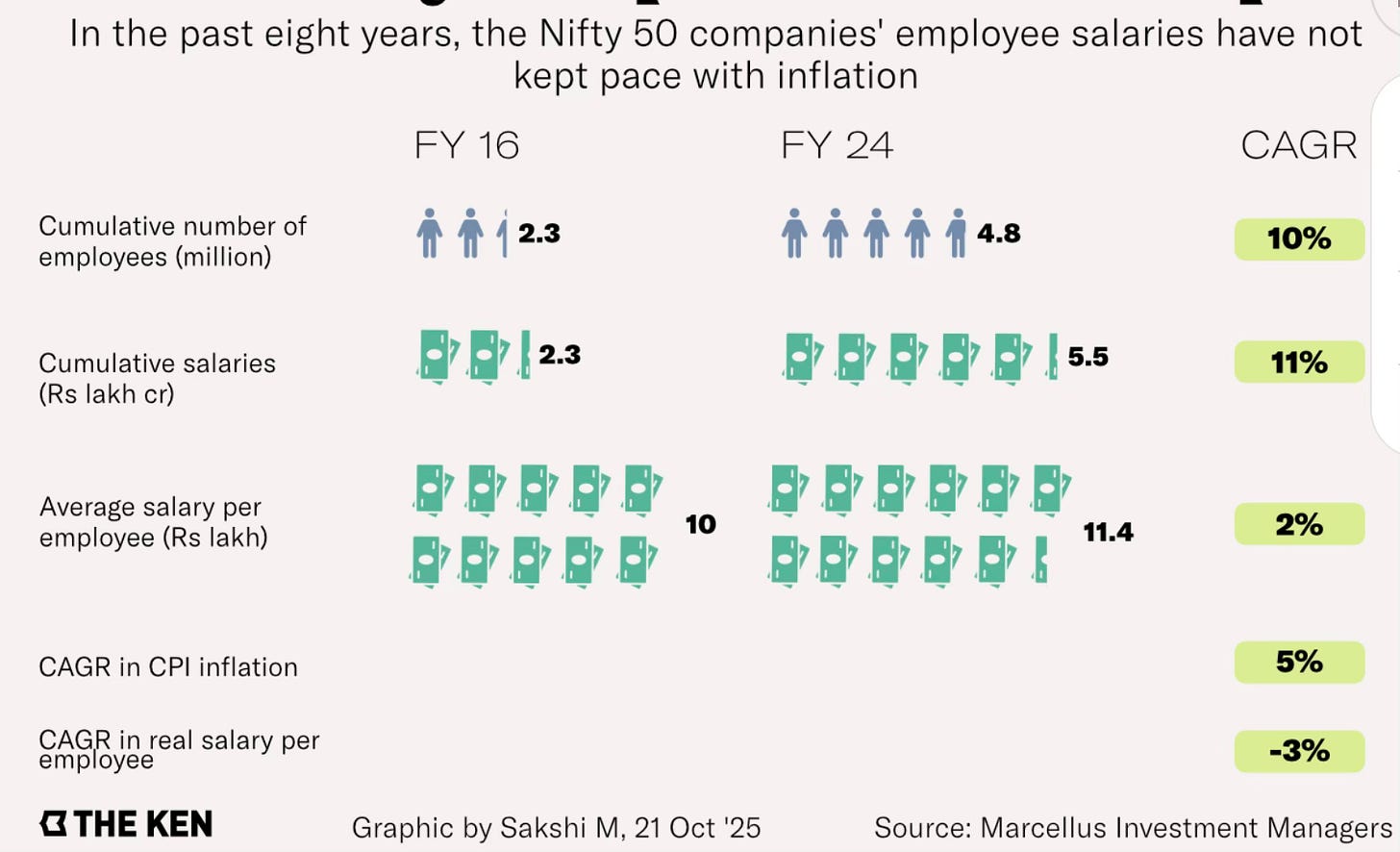

This flush of free cash flows has also not translated into meaningful increases in employee salaries that could have contributed to the emergence of a broader consumption class.

And now the industry faces disruption and job losses from AI technologies and the emergence of vertical integration of activities within multinationals in the form of Global Capability Centres.

6. Finally, contrary to the impression created by recent public debates, Indians may be among the hardest-working people.

Since the 1970s, Indians on average have consistently worked more than 2,000 hours per year, even as other developed and developing countries saw this figure decline as productivity rose… As per an ILO database, Indians worked the highest average hours — at 56.2 hours per week or 11.2 hours per day for a five-day week — among 56 countries for which 2024 figures were available. In 2023, too, India topped the list (56 hours per week) among the 92 countries for which data were available… figures compiled by Our World In Data (OWID), a research publication based at the University of Oxford in the UK, showed that the average Indian worked 2,383 hours a year (or 6.5 hours per day, including weekends and national holidays, or 9.5 hours per day assuming 250 working days per year) in 2023. This puts India at ninth on the global list of the most time spent working.

However, the increasing hours of work are not translating into higher productivity. In fact, labour productivity is not only stagnating but may even be declining in certain sectors.

As per the Reserve Bank of India’s (RBI) KLEMS database — which analyses industry-level data focusing on capital, labour, energy, materials and services to measure economic growth, productivity, and efficiency — since 2019, at least nine industries have recorded a decline in labour productivity, including key sectors such as mining. Five other industries, including construction, have only seen marginal growth in the same period among a total of 27 industries analysed. This declining productivity is despite the share of labour’s income in the industries’ gross output remaining largely unchanged since 2019, barring four industries that reported small increases in labour’s income share. The 2024-25 Economic Survey found that while corporate profits grew by 22.3% in 2024, employment only grew by 1.5%, and the expenditure on employees fell to 13% from 17% in 2023. This indicates a preference for cost-cutting over workforce expansion, coupled with declining or stagnating wages, all of which are contributing to labour productivity and output lagging, apart from growing inequality.

In India’s case, the problem appears not to be working more hours, but rather working more productively. This productivity is a measure of both the use of capital and technologies, and most importantly, the quality of education imparted. The latter is arguably the biggest development and economic growth problem that we have, and one which requires prioritised, national engagement.

In conclusion, to make a high-level sense of the direction of the Indian economy, we can use a framework involving four categories of contributors to economic growth. The first consists of inputs like physical infrastructure and financial capital. The second involves the quality of human capital formation. The third consists of enabling factors like laws and regulations. And finally, there’s the state capability to formulate laws, execute contracts, and deliver quality public services.

While much has been and is being done on the first and third, the second and fourth categories remain inadequately acknowledged and addressed. They are critical since broad-based economic growth and productivity enhancements cannot come without these contributors.

No comments:

Post a Comment