The US tariffs have sparked intense debates in India about the economic responses needed to address a challenging situation.

On the one hand, it has reignited efforts to focus on self-reliance to insulate the economy from such future shocks, likely given the prevailing protectionist sentiments and the rising geopolitical uncertainties. On the other hand, some worry that this would mark a return to some form of the license-permit raj.

It has also sparked another debate between those who argue that India’s private sector’s lack of ambition, low risk appetite, weak ability to build, and general lack of global competitiveness are responsible for its economic dependence on others, and those who blame this failure on stifling government regulations and a lack of support.

In this backdrop, it’s useful to step back and examine the problem using a simplified model to understand the contributors to economic competitiveness. It has four dependent variables:

Internal economic conditions (physical infrastructure, financial capital, human resource availability, etc.),

Internal business conditions (regulatory environment, business creation and growth enablers, trade policy, market competition, etc.),

Domestic demand (affordability, size of consumption class, price sensitivity, demand for quality, etc.), and

Private sector culture

While much has been written about the first two, and rightly so, the last two do not get anywhere near the attention they deserve. If anything, the last in particular is surprisingly and widely overlooked in public debates.

I have blogged about the importance of domestic demand here, in that businesses need a large enough quality-conscious consumption class to be able to have the incentives to maintain quality and innovate. A mostly price-sensitive customer base, however large, that discounts quality for price, can be a significant deterrent to investments in quality and innovation. This is an important demand-side constraint.

This can be significantly addressed if the businesses are exposed to global competition and pursue export markets. This is the point about export-competition (and letting go of the failing firms) that Joe Studwell and others have chronicled in the context of the high-performing Northeast Asian economies. All of them pursued protectionist policies but vigorously enforced export competition through public policies.

It’s no exaggeration to say that the last variable, private sector culture, does not get any attention in mainstream debates. This is understandable given the difficulties with quantifying it and the limited research and studies that document the issue of business culture from the perspective of economic competitiveness.

In broad terms, we can evaluate business culture in terms of an innate quest for productivity, especially among the large firms. This has an economy-wide domino effect through multiple channels - suppliers, learning by doing, competition, etc.

This culture is manifest in their R&D investments, attitudes towards innovation, focus on quality, the extent of scale manufacturing, intentions to invest for the long-term, and business dynamism in terms of ambition to continuously move up the value chain, expand business (scale manufacturing), pursue global markets, and so on, and generally aspire to be at the cutting-edge of the technology frontier and be a global leader in their industry.

While, there’s some endogeneity between economic conditions and government policies and some of these attributes, it can also be argued that for the larger firms in an economy like India, many, if not most, of these attributes are within their control.

Unfortunately, when evaluated against these metrics, Indian firms, especially the larger ones, fall woefully short. The low R&D investments are an egregious illustration, as also a lack of scale manufacturing, and a near total absence of global brands. Indian firms are conspicuously absent in the echelons of global business. This is generally true of the largest firms across sectors, and the software and pharmaceutical sectors in particular. In general, corporate India, across sectors, suffers from a lack of business dynamism. Even the country’s startups have struggled to imbibe this culture, preferring mostly to engage in copycat innovations.

This disturbing deficit in the culture of private sector competitiveness also assumes significance given the history of global economic development.

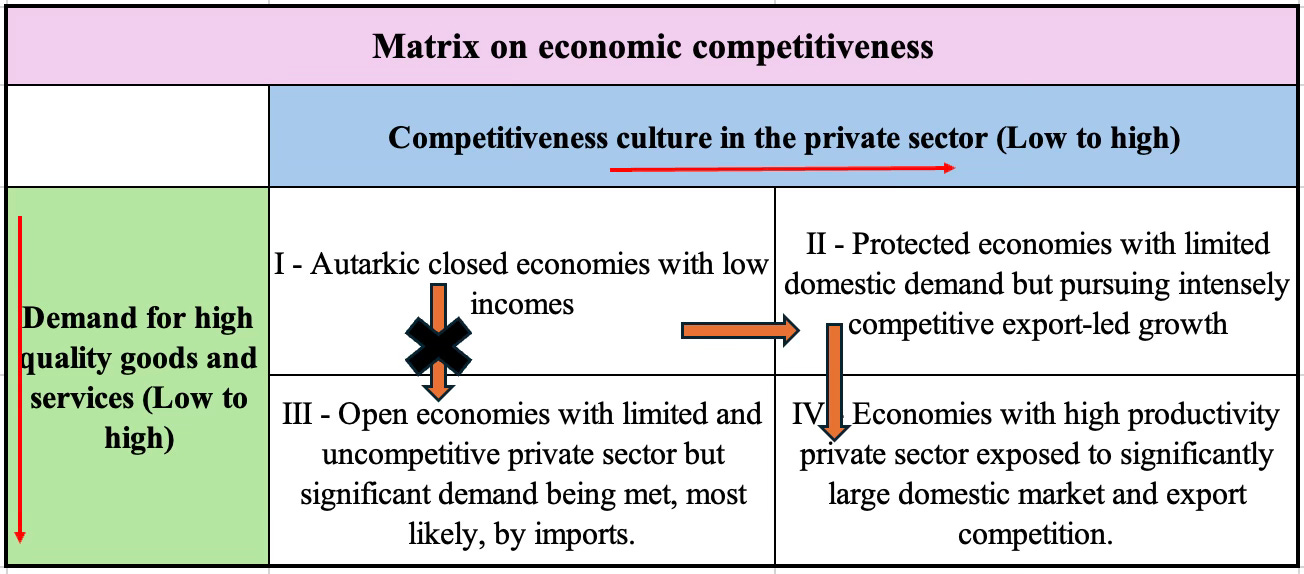

The figure below captures how domestic demand and corporate culture interact with each other.

There are two broad economic growth trajectory choices available for countries like India that are transitioning to open economies. One, move from a relative autarky characterised by a poor competitiveness culture, to a liberalised regime without the private sector becoming competitive. In today’s world, this would be akin to becoming importers of (mainly) Chinese goods, allowing the existing manufacturing base to erode further and the private sector to remain uncompetitive.

The second option is to build up private sector competitiveness by maintaining adequate protections and then gradually opening the economy as the private sector competitiveness rises. This strategy is especially relevant given Chinese import competition, which can quickly emasculate domestic manufacturing capabilities. Further, given the small size of the quality-conscious domestic consumer base, the only way for competitive domestic firms to emerge is by manufacturing for exports. This is essentially about Make in India for the World.

This has been the trajectory followed by all the Northeast Asian economies recently, and the European economies long ago. Admittedly, there are strong headwinds that have emerged in recent years that come in the way of the pursuit of such growth.

In conclusion, if India is to emulate the Northeast Asians, it’s essential to develop a competitive private sector. As discussed above, this is primarily a work for the private sector to pursue internally, with corporate India taking the lead.

No comments:

Post a Comment