As President Trump wages war on trade deficits and flaunts tariffs indiscriminately, some proposals are on the table to address the problem. Three in particular are getting attention.

Robert E Lighthizer, the US Trade Representative in the first Trump administration, and arguably the ideological godfather of the Trump administration’s push against China and embrace of tariffs, has advocated a new trade regime among countries with democratic governments and mostly free economies. The main underlying principle behind this regime would be long-term trade balance.

The regime would have a two-tier tariff structure. The countries outside the regime will pay a higher tariff while those within would pay lower tariffs, which, however, could be adjusted over time to ensure balance. If a country runs large and persistent surpluses, others would raise tariffs on it so as to bring it down over a reasonable time. This would ensure balance within the entire group over time, and not across country pairs or smaller groups every year.

Another proposal, published in November 2024 by Stephen Miran, the current chair of the Council of Economic Advisers in the Trump administration (and then at Hudson Bay Capital), points to the work of Belgian economist Robert Triffin from the early 1960s in the context of the Bretton Woods system of fixed but adjustable exchange rates. The Triffin Paradox highlighted the dilemma, faced by a country whose currency serves as the global reserve currency, between maintaining its own economic stability and ensuring global liquidity.

The global demand for dollars can be met only with persistent deficits. America must supply dollars to enable foreigners to buy its Treasury Bonds. This keeps the dollar overvalued for some time and erodes America’s manufacturing and export competitiveness. However, in the long run, persistent deficits must weaken the dollar and erode its credibility as a reserve currency.

In Triffin world, the reserve asset producer must run persistent current account deficits as the flip side of exporting reserve assets. USTs become exported products which fuel the global trade system. In exporting USTs, America receives foreign currency, which is then spent, usually on imported goods. America runs large current account deficits not because it imports too much, but it imports too much because it must export USTs to provide reserve assets and facilitate global growth.

Since President Trump wants to lower the deficit without diminishing the dollar’s global influence, unilateral actions like devaluation or monetary loosening are risky and unlikely to work. Even tariffs have their limitations. Miran, therefore, proposes that the US offer its trade partners a deal. The economic side of the deal will involve the maturity transformation of US Treasuries by “persuading” foreign holders to switch from short-term to perpetual dollar bonds. In return, the US could offer a political alliance and its defence umbrella.

This is a monetization of the American role in the post-War Western alliance. In fact, Martin Wolf describes this proposed global exchange rate management mechanism as a form of “protection racket”. Miran writes

America provides a global defense shield to liberal democracies, and in exchange, America receives the benefits of reserve status—and, as we are grappling with today, the burdens. This connection helps explain why President Trump views other nations as taking advantage of America in both defense and trade simultaneously: the defense umbrella and our trade deficits are linked, through the currency… Such an architecture would mark a shift in global markets as big as Bretton Woods or its end. It would see our trading partners bear an increased share of the burden of financing global security, and the financing means would be via a weaker dollar reallocating aggregate demand to the United States and a reallocation of interest rate risk from U.S. taxpayers to foreign taxpayers. It would also more clearly demarcate the lines of the American defense umbrella, removing some uncertainty around who is or is not eligible for protection.

Coming from two of the most influential and credible insiders, these must be taken seriously.

However, without getting into the details of either, the biggest challenge with both proposals is their implementability. Both assume an alliance led by the US, where allies accept some form of explicitly acknowledged US suzerainty and also bear the costs of maintaining that protection umbrella.

Lighthizer proposes to create a new trade regime among allies. Thanks to its several moving parts, its operationalization will be very complicated. The biggest challenge would be in getting countries to exercise voluntary self-restraint and raise tariffs. The distortions arising from such complex forced incentives can be unpredictable and self-defeating.

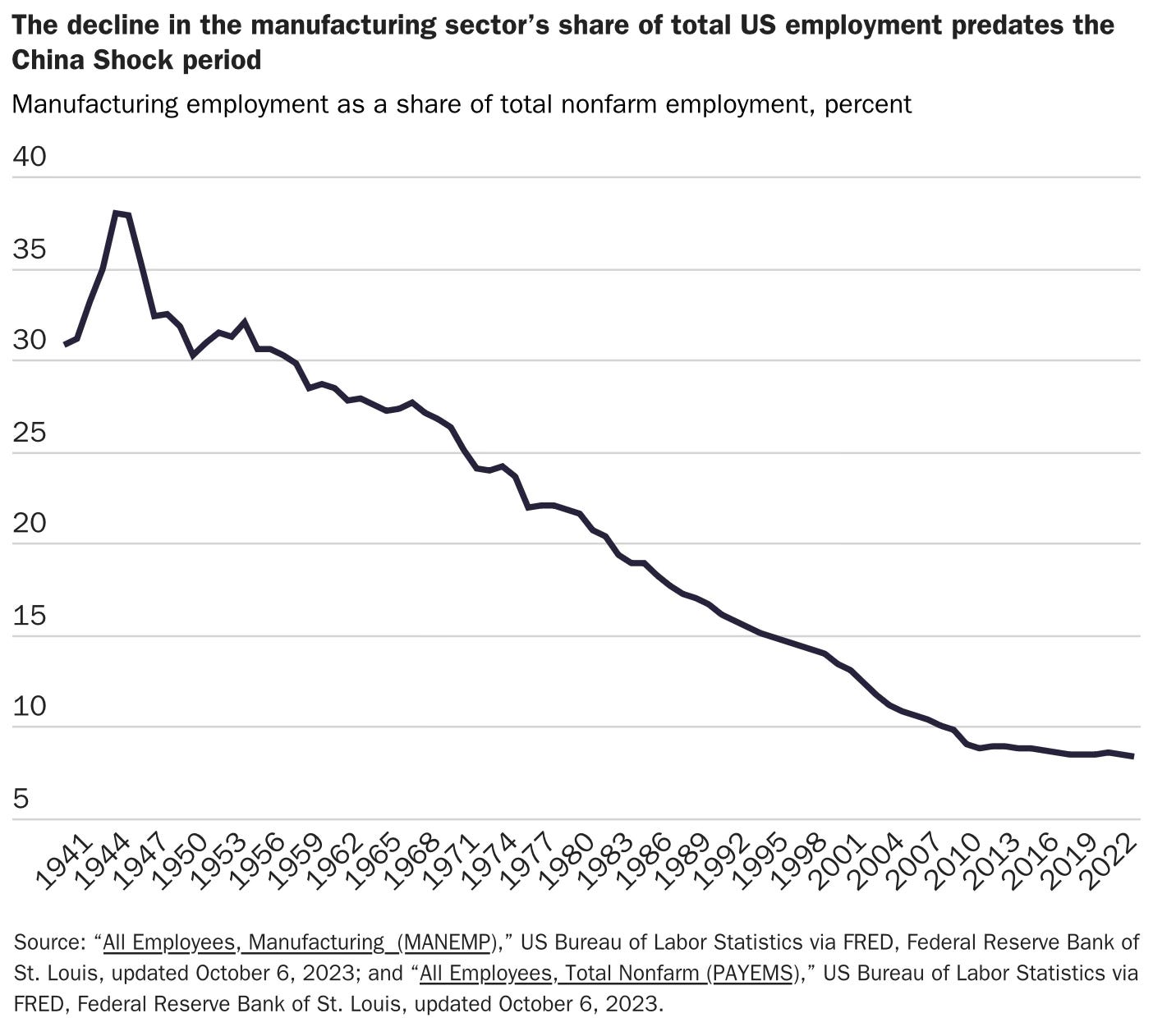

Given the events since President Trump’s inauguration and his track record, it’s unlikely that any country will be “persuaded” into the arrangements proposed by Miran. So, it looks dead on arrival. In theory, too, its assumption of a causal link between the US manufacturing decline and the dollar’s role as a reserve is questionable. The former is a long-term secular trend..

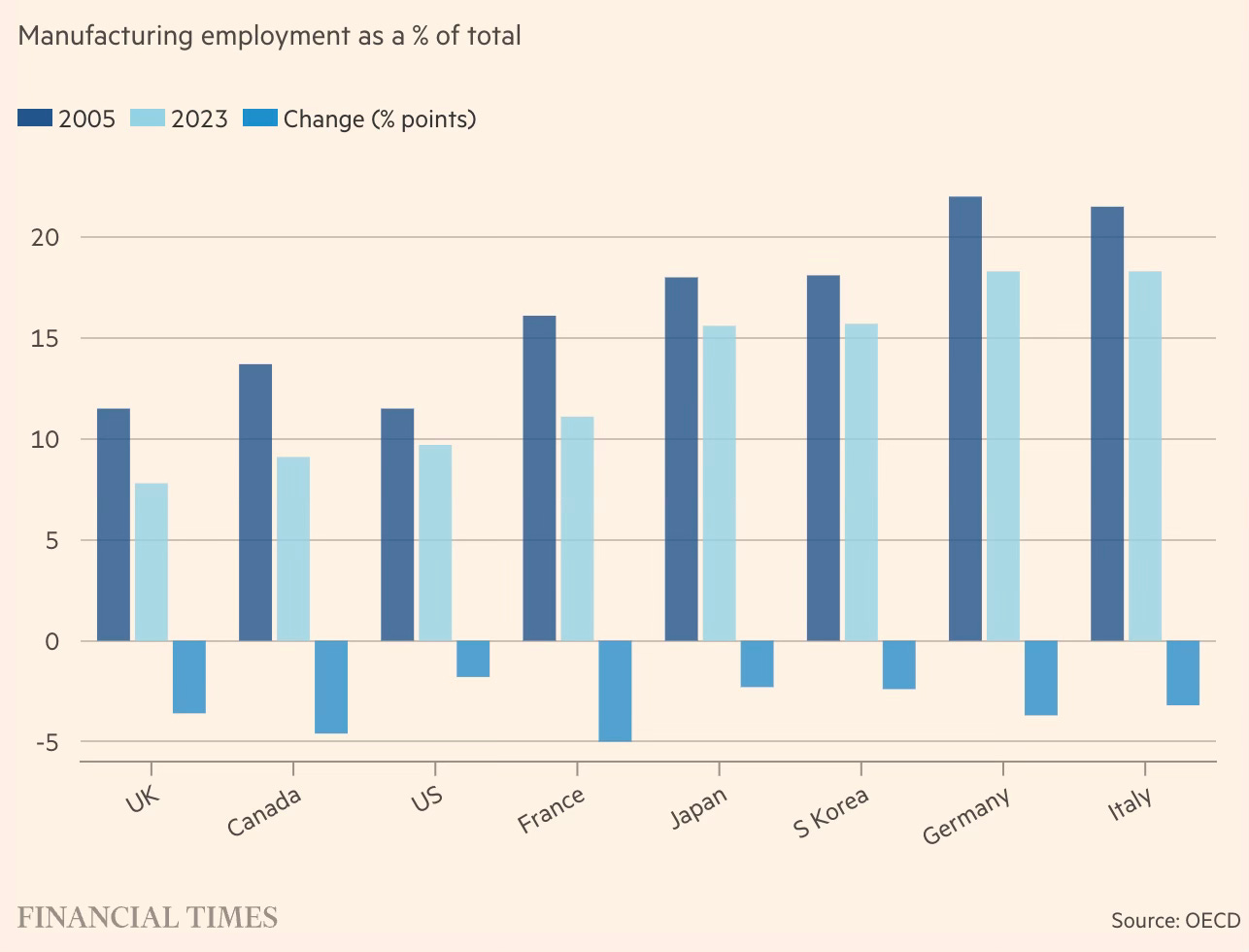

Besides, it’s also shared by the US with other advanced countries. The US neither has the highest nor lowest decline in the share of manufacturing employment.

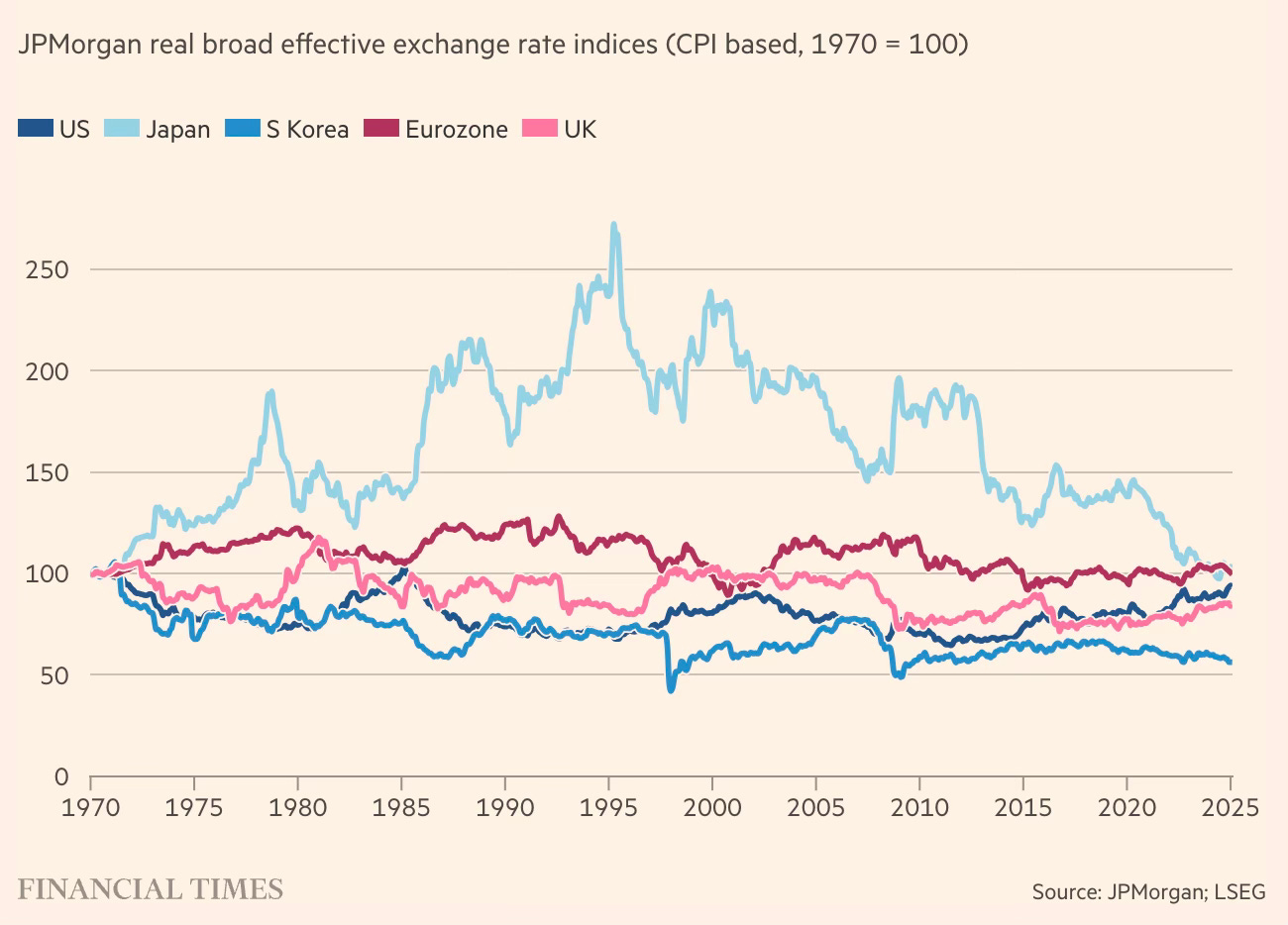

As Wolf writes, for all of Miran’s argument about the long-term erosion of the credibility of the reserve currency, the USD exchange rate has been remarkably stable.

A third proposal is that espoused by Michael Pettis, who points to a link between persistent trade deficits and capital inflows. Pettis argues that capital inflows and deficits are two sides of the same coin, with the former boosting the dollar’s value, misallocating resources through excessive financialisation, and eroding the country’s industrial base. So, he advocates taxing capital inflows.

Gillian Tett writes about this idea gaining currency.

Six years ago, Democratic senator Tammy Baldwin and Josh Hawley, her Republican counterpart, issued a congressional bill, the Competitive Dollar for Jobs and Prosperity Act, which called for taxes on capital inflows and a Federal Reserve weak-dollar policy. The bill seemed to die. But last month American Compass, a conservative think-tank close to vice-president JD Vance, declared that taxes on capital inflows could raise $2tn over the next decade. Then the White House issued an “America First Investment Policy” executive order that pledged to “review whether to suspend or terminate” a 1984 treaty that, among other things, removed a prior 30 per cent tax on Chinese capital inflows… And Pettis’s ideas seem to be influential among some advisers, such as Treasury secretary Scott Bessent, Stephen Miran, the chair of the Council of Economic Advisers, and Vance.

While Lighthizer proposes the use of tariffs directly and Miran’s preferred instrument is the US Treasuries, Pettis advocates taxing capital flows. As I have written in my co-authored book, financialization has gone too far with adverse consequences and it’s essential to throw sand in the wheels of cross-border finance. However, given the scale and interconnectedness of cross-border flows, only the US can restrain such financialisation. Pettis's suggestion is therefore a step in the right direction.

But it too, like the others is unlikely to do much in reversing the US trade deficits and manufacturing.

The central problem that Trump wants to solve is the persistent US merchandise deficit, and tariffs are his primary weapon. The underlying premise is that tariffs will discourage imports and encourage domestic manufacturing. Unfortunately, such single-instrument approaches to complex problems are not only blunt but also likely to detract from focusing on the deeper underlying causes.

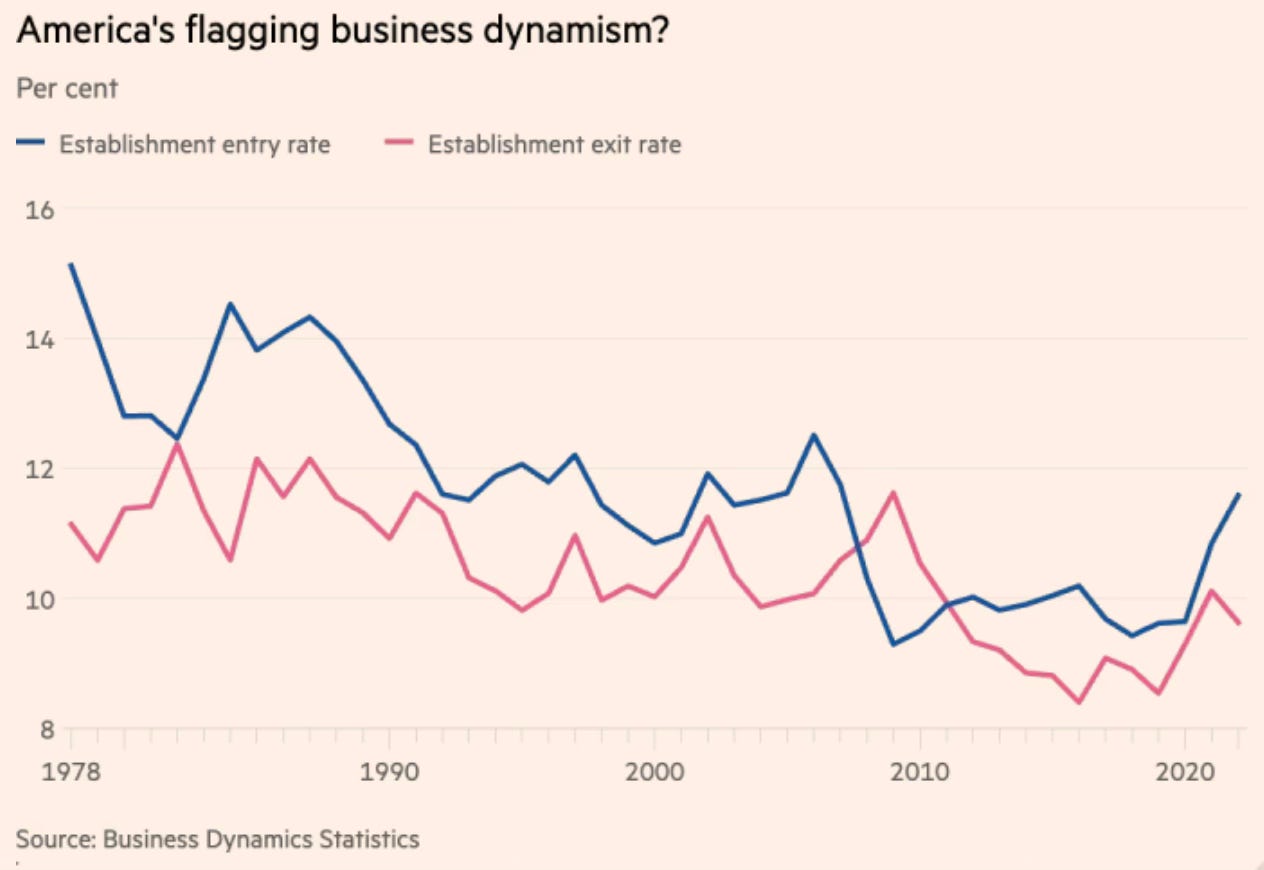

Apart from reversing the long-term trend of manufacturing decline, there are several problems to be overcome like declining business dynamism, productivity growth, excessive financialisation, and high levels of business concentration.

Fortunately, thanks to the policies initiated by President Trump in his first tenure, the US has made a good start in its endeavour to redress the imbalances and restore its manufacturing competitiveness. The tariffs and restrictions on China had reversed the course of US deficits with that country. Others too had realised that the Chinese subsidies and industrial policy since the pandemic and the bursting of its real estate bubble had unleashed excess capacity and dumping, which was shutting their local manufacturing and eliminating jobs. They were retaliating and putting up restrictions in various forms.

The momentum on all these must be maintained and hastened, especially by stopping Chinese exports from finding their way through “connector” countries. Addressing the world economy’s China problem is a challenging task that requires the US to coordinate and carry together its allies and other major economies. Unfortunately, the current policies of the Trump administration run the risk of hurting progress on all these fronts.

The wave of industrial policy actions, especially the large schemes announced by the Biden administration in the US, are also steps in the right direction. There are clear signatures of a spike in US manufacturing investments and reshoring of supply chains. This momentum too must be kept up. Here too, there’s a risk that the Trump administration may not only take the foot off the pedal but even reverse course on industrial policy.

Finally, the dominance of the plutocrats from Wall Street and Big Tech in the Trump administration poses considerable risks in taking action in important areas like anti-trust and financialisation. Ultimately, it may be too much to expect a businessman to free America from the clutches of plutocracy.

No comments:

Post a Comment