This post is a compilation of a few good long reads.

1. A fascinating article on Tokyo’s Toyosu, the “world’s greatest fish market”, employing 42000 people, transacts more than a quarter of all fish sold in Japan, and with an average daily sales of ¥2bn ($12.9m). The market, which opened in 2018 to replace the old Tsukiji market, aggregates the finest fish from all over the world and conducts auctions where chefs from across the world are bidders.

Many assume that tuna bought from Japan is superior because of the species, or where they are caught. That is partly true: bluefin tuna, which tend to be fattier than other species, fetch higher prices than the leaner bigeye and yellowfin, while skipjack and albacore often end up in cans. But holding species equal, the way a fish is caught and processed matters immensely to how it tastes—and therefore to its value.

Expert tuna fishermen avoid nets, which make the creature thrash around in fear, producing lactic acid and adrenaline that mar its taste and texture. Instead, they reel it in slowly, and then begin a process called ikejime. First, they drive a spike into its brain, killing it instantly to avoid a stress reaction that ruins the meat. Then they remove the tail fin and slice beneath the gills to bleed the fish while its heart is still beating. Blood contributes to spoilage through bacterial growth; properly bled fish will last longer… With the tail fin removed, they run a long, stiff wire into the fish to destroy its spinal cord and prevent rigor mortis. Once killed, bled and paralysed the fish goes into the freezer—or, if sold fresh, is submerged in an ice-and-water slurry.

This is a nice description of the auctions process

Before the auction, the floor is a hive of silent activity… Atop each frozen tuna sits a sticker detailing provenance and weight, as well as a thick slice cut from the tail so buyers can see the colour. Some use hooked picks to dig out small chunks of flesh, kneading it as they walk around to determine the fat content through feel. Most carry clipboards; some acknowledge each other with a brief nod. Mekiki, experts in fish evaluation, set the floor price for each fish.

Around 5.30am an auctioneer rings a bell and sales begin. Fresh bluefin tuna fetch the highest prices: an average of $25 per kilo between January and August 2024, with the priciest fish fetching $750,000 on January 5th. Auctioneers chant rhythmically, keeping up a patter as buyers show interest with idiosyncratic hand signals and, because two houses often hold auctions simultaneously right next to each other, with eye contact. Buyers wear baseball caps with plastic plackets bearing the names of their firms; officials from Tokyo’s government, which owns the market, wear blue caps and watch out for collusion. The action is hard to follow, relying on subtle gestures and clues… By 7am the auction floor is mostly empty and being hosed down… By 8am the tuna has been butchered and sent on its way: some to restaurants across Japan; some, still frozen, stuffed into styrofoam boxes and flown to New York, Sydney or Singapore. But some, perhaps, will find its way upstairs, to the first-rate sushi joints on the fourth floor, which open just after the tuna auction ends and close by mid-morning.

This is about the market participants, which makes it a form of managed capitalism.

Only five companies are allowed to sell, and only certain species are flogged. Wholesalers are quick to say that they do not want to put their rivals out of business. Threats to their livelihood come not from neighbours, but from retailers bypassing the market and buying directly from fishing firms. Many outfits at Toyosu stretch back generations, often linked through kinship and marriage. Good behaviour and bad are remembered, and in time rewarded and punished.

In his magnificent book “Tsukiji: The Fish Market at the Centre of the World”, Ted Bestor, an anthropologist, argued that intermediate wholesalers “define much of the character of the marketplace”. The seven big wholesalers deal with shippers and suppliers; intermediates sell to restaurant groups, supermarkets and chefs. Many are family firms. The smallest may have just two employees: the husband or son who handles the fish, and the wife or mother who keeps the books. (Toyosu remains very male; book-keeping is the only job mostly held by women.)

The number of intermediate wholesalers has fallen from nearly 1,700 in the mid-1960s to 457 today. Many small firms refused, or were unable, to move to Toyosu. Others have merged. They are laid out on what look like streets that line their building’s ground floor: cheek by jowl, with some large enough to have hefty fish tanks, a dozen workers and butchering tables big enough for an entire tuna and an arm-size knife to cut it. Some specialise, selling just tuna or eel, but many are generalists… Relationships between wholesaler and buyer can last years, even generations. The former’s success depends not just on expertise in choosing fish, but on knowing clients’ tastes and anticipating their needs… most chefs have long relationships with specific wholesalers, and the former would no more desert the latter to save a few yen than the latter would overcharge the former.

This is similar to the traditional relationships that exist in many settings in India, none more so than that of the Arhatiyas, traders, and farmers in Punjab and Haryana. While mainstream discourse tends to demonise Arhatiyas for exploiting farmers, it glosses over a more nuanced and layered set of relationships and the useful roles performed by them.

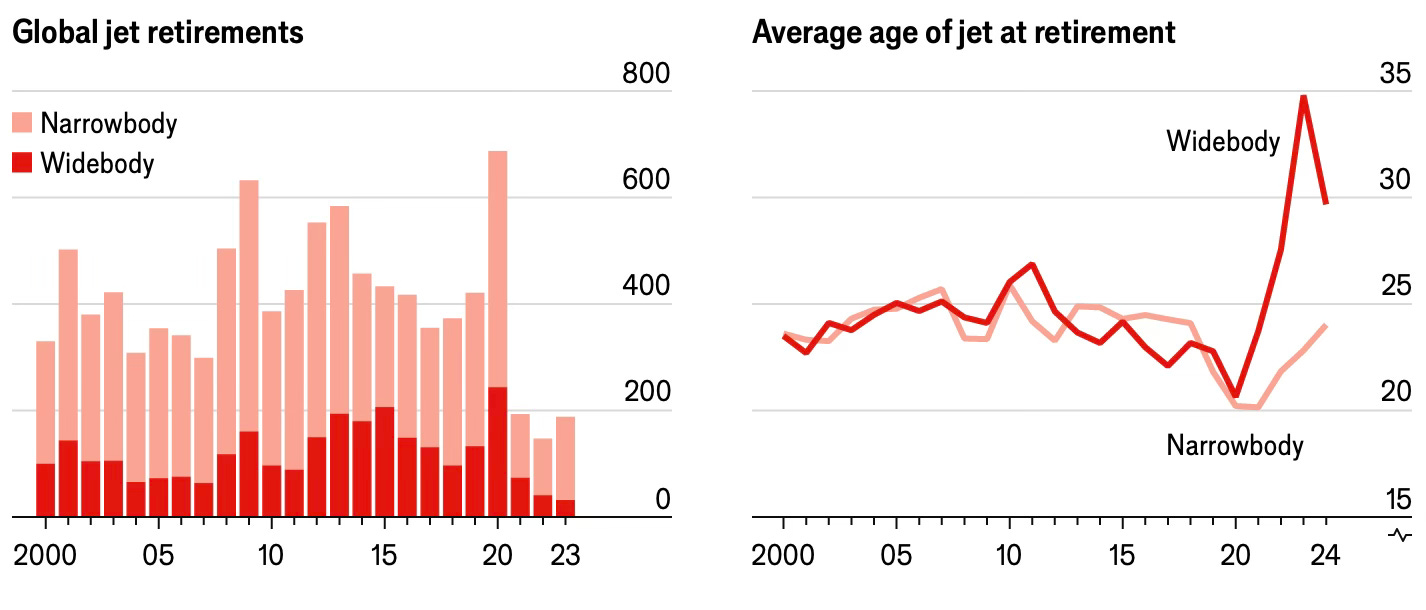

2. On the after-life of retired airplanes.

A Boeing 747 has 6m parts, many of which can be reused. Parts need to be certified and have a comprehensive maintenance history, or else their provenance becomes suspect and value plummets. The robust-looking outer covering is in fact a millimetre-thin “skin” of aluminium alloy covering a metal frame, insulated with foam. That skin is harvested by firms such as Planetags, which turns it into keychains and other keepsakes. The most valuable part is the engine, usually the first thing to be harvested… Cockpit instruments can be removed and reused in other aircraft of the same type. Sometimes the entire cockpit is repurposed as a simulator for pilot training… Higher-class seats may be sold to other airlines or hobbyists but economy seats are, on the ground as in the air, the least desirable things on a plane.

Consider the Boeing 777. It has 132,500 unique parts and some 3m in total, including bolts and rivets. Beneath the soft, rounded surfaces of the passenger cabin is a bewildering tangle of sensors, radars, pumps, pistons, cylinders and drums. Miles of wires connect avionics to the cockpit. Hydraulic systems move the rudder or wing flaps or brakes. Airlines need a reliable supply of all these bits and pieces. The global aviation industry would grind to a halt without them… The industry’s insatiable appetite for parts is fed by retired planes…

The first things to come off when a plane arrives in Arizona are the engines. Next to go is the landing gear. Avionics, instruments, hydraulics and other components are either harvested and stored or removed gradually on the basis of need. Cockpits are sometimes removed to be converted into flight simulators for pilot training. Luxurious seats at the front of the plane find new homes with second- or third-tier airlines or in the basements and garages of aviation aficionados… Once everything—engines, components, interiors—has been stripped out, the metal structure is all that remains. Made of high-quality aluminium alloy, it commands premium prices in scrap. Airbus and Boeing both estimate that around 90% of their aircraft by weight is recycled or reused in some form.

On modern aircrafts

The latest generation of long-haul planes—Boeing’s 787 “Dreamliner” and the Airbus A350—is less noisy and more stable in turbulence. The new jets can manage higher humidity levels, lowering the chances of dehydration for travellers, and maintain higher cabin pressures that feel closer to conditions on the ground… New planes are also more efficient. Fuel is the single largest cost for any airline. Engines and weight are major factors in determining consumption. The biggest modern aircraft have just two engines compared with four on the 747 or the enormous Airbus A380 double-decker, and much of the airframe is made of light composite materials, such as carbon fibre, instead of heavier aluminium alloys. Airbus boasts that the A350 consumes 25% less fuel per seat than its predecessors, producing comparably fewer emissions.

3. By any yardstick, Vietnam should count as one of the most remarkable economic successes in history. The New York Times has an excellent article that describes how North Vietnam broke away from the prosperous and industrialised South to lead the country’s spectacular economic success over the last two decades.

This is a very good description of the transformation

In 1954, after separating from France to become an independent nation, it was one of the poorest and least-developed countries in Asia, relying almost entirely on subsistence farming. Haiphong, the north’s main port, was pounded by the U.S. military with some of the heaviest bombing raids of the war, and in the decade after unification in 1975, all of Vietnam became what one scholar called “a poverty-stricken society beset by a stagnant economy.” Today, double-digit growth rates in the north are the norm, and Haiphong is a modern metropolis of two million people connected to Hanoi by a new highway. Cranes swing like weather vanes above more than a dozen construction sites. New bridges cross a river twisting through the city, where piers at industrial parks help ships move to one of the busiest ports in the world.

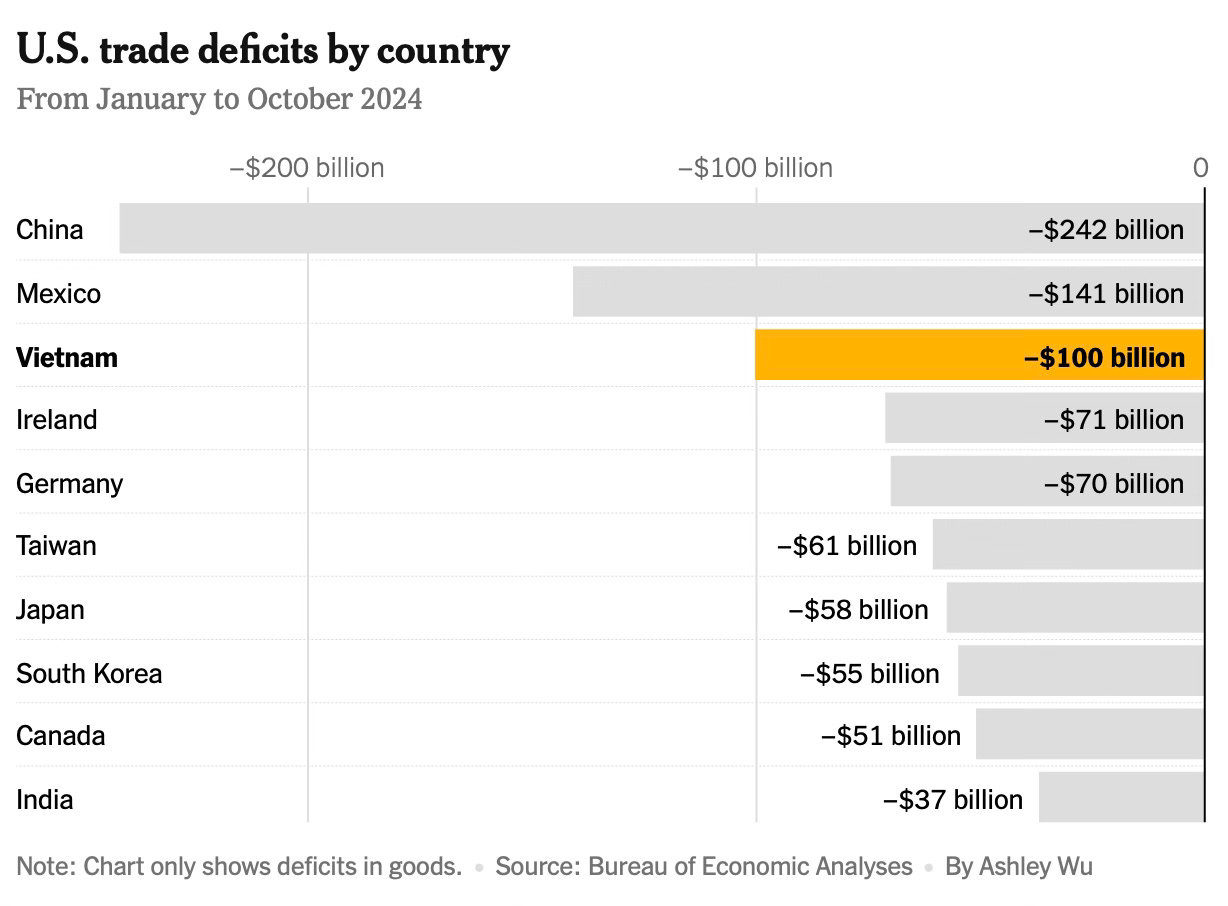

The election of Donald Trump in 2016 and his tariffs on Chinese imports and other trade restrictions were triggers for North Vietnam’s take-off. Now, with the re-election of President Trump, the wheel may have turned the full circle.

Six years ago... President Donald J. Trump hit China with tariffs, igniting a global search for alternatives to Chinese manufacturing. Few nations, if any, have benefited more than Vietnam from the scramble that followed — especially north Vietnam, historically an economic laggard compared to the more cosmopolitan south. Around Haiphong, a few hours’ drive from China, factories bloomed. The LG plant expanded exponentially; the industrial park nearby filled up with Chinese companies adding production abroad. Rural hamlets... grew almost overnight into boom towns of 30,000... Mr. Trump has vowed to punish countries that have large trade surpluses with the United States, and Vietnam now ranks third on that list, behind only China and Mexico. Officials in Hanoi say they worry... that Vietnam will be singled out for tariffs while competitors avoid Mr. Trump’s blacklist. South Korean companies (including LG and Samsung) are Vietnam’s biggest foreign investors, and some have already paused expansion plans, waiting on Washington... No matter what happens next, America’s once-and-future president can safely say he helped make north Vietnam great again.

Vietnam’s worry comes from a graphic that drives most of President Trump’s foreign and trade policy actions

While Vietnam may have become a victim of its success, it may be simplistic to lay the blame on the relabeling of Chinese products.

Between 2017 and 2023, foreign investors committed $248.3 billion to Vietnam for 19,701 projects, according to an analysis by Le Hong Hiep, coordinator of the Vietnam studies program at the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute in Singapore. That’s more than half of all foreign investment since Vietnam opened its economy in the late 1980s. Vietnam’s growing trade surplus with the United States — reaching $104 billion last year, up from $38 billion in 2017 — has led to accusations that China uses Vietnam as a warehouse, rerouting its products to avoid tariffs. Chinese imports and investment have soared... Of the roughly 120 Japanese companies using government diversification subsidies, over 50 claimed them for Vietnam, more than any other country, according to Japanese officials...But in a country as wary of its neighbor as Vietnam, where 1,000 years of Chinese colonization lingers in national memory, the boom is by no means owned or operated by Beijing... A recent Harvard Business School study showed that illegal tariff avoidance was more rare than the trade imbalance might suggest — representing between 1.8 and 16.1 percent of exports to the United States in 2021. Researchers found that most exporters were making new products with inputs from many locations and local investment, not just relabeling Chinese products as Vietnamese.

What explains the success of the North?

Bruno Jaspaert, chairman of the European Chamber of Commerce in Vietnam and the chief executive of DEEP C, which runs industrial parks around Haiphong, said the waterway was just one regional advantage. Northern provinces have also had leaders better connected to Hanoi, yielding more infrastructure investment, plus more open, affordable land. Compared to the south, where an industrial base left over from the war made it easier for companies like Nike to get going in the 1990s, Mr. Jaspaert said the north “started later, they can plan better and they are also much faster.”

Pointing out the window of his office to Haiphong’s new city hall, surrounded by new apartment complexes, he emphasized that none of that was there when he moved to Vietnam in 2018. Northern Vietnam was already growing then, in a country that lifted 40 million people out of poverty from 1993 to 2014. But American tariffs became an economic accelerant — lighter fluid poured on a steady flame. And in the north, an epicenter of ancient Vietnamese civilization and Communist revolution, government officials’ quick action coincided with foreign investors’ own sense of capitalist urgency. Mr. Jaspaert said production decisions that once took 18 to 24 months now take six to nine. And while the south stagnates somewhat (Ho Chi Minh City’s subway line remains incomplete after 20 years of construction), the north races on. DEEP C’s revenues and profits have quintupled since the Trump tariffs…

Villages like Mr. Van Thinh’s have been transformed. When the LG plant expanded in 2019, the narrow streets of nearby hamlets quickly turned into commercial strips with restaurants and bold-colored barbershops for workers who make a solid local wage of around $400 to $550 a month. Every spare piece of land has been turned into worker housing. Mr. Van Thinh now manages 35 rooms with his family. Nearby, Pham Thi Cham, 55, drained a backyard pond where she raised fish to build eight rooms that she rents out for about $60 a month. Many of the workers come from central Vietnam. Instead of going south, they came north.

4. Bloomberg has a long read on the spectacular rise of Chinese automaker BYD, Build Your Dreams.

After increasing its annual sales in China 15 times over, to 3 million cars in only three years, BYD is now exporting to roughly 95 markets, including 20 new ones this year. The company is building, has recently opened or has announced plans for assembly plants outside China in 10 countries on three continents. The speed and scope of this expansion have caught the global auto industry off guard and triggered protectionist tariffs in the US and EU… BYD’s electric and hybrid vehicle car sales rocketedfrom just under 180,000 in 2020 to 1.86 million in 2022, giving (it)… the cash to fund a new overseas push…

BYD, which stands for “Build Your Dreams,” is the brainchild of Wang Chuanfu, a 58-year-old battery scientist who in the 1990s saw an opportunity to start a rechargeable battery company to challenge Japan’s hold on the industry. It began by focusing on batteries for mobile phones and power tools, but in 2003 it decided to pursue cars. Wang’s battery and manufacturing innovations, cushioned by China’s EV-friendly government policies and the scale of its domestic auto market, have helped BYD do what Tesla Inc., Ford Motor Co. and the rest of the auto industry haven’t: build an affordable electric car for the masses and make money doing it. Since introducing a new battery technology in 2020, BYD has gone from being an also-ran in China’s crowded car market to cracking the top 10 automakers in the world…

It also wants to do what no Chinese carmaker has ever done: become a globally recognized consumer brand. It’s hoping to transcend geopolitics through the appeal of a plug-in hybrid sedan that can go 1,200 miles without stopping at a pump or a charger. Stella Li, BYD’s executive vice president and the face of its global expansion, says she wants consumers to see BYD as “a technological pioneer in changing the world.”… a playbook she has used whenever entering a new market: Do intensive market research; win hearts and minds on the ground; then tap BYD’s vast product portfolio to deliver whatever the locals want. One city might want a rail transit system, another an electrified municipal bus fleet. In London she started out with electric city buses to introduce the brand, then moved on to passenger cars. She did the same in Jakarta. In Brazil the playbook was jobs… As in Brazil, Li formed a partnership with taxi drivers through a ride-hailing app in Mexico City. She sold electric work trucks to Mexican conglomerates such as Grupo Bimbo SAB de CV and Cemex SAB de CV, and cut a deal with El Puerto de Liverpool, Mexico’s ubiquitous luxury department store chain, to sell EVs and at-home chargers at the mall.

The stories of Wang and Li are inspiring

Wang was thinking about cars as early as the 1990s. To him, BYD had always been more than just a low-cost battery manufacturer. It was a research and development machine that would use rechargeable batteries as a launchpad for products that could change entire industries. The orphaned son of farmers in rural Anhui province, he was raised by his siblings and earned an undergraduate degree in metallurgical physical chemistry in 1987, then a master’s from the Beijing Non-Ferrous Research Institute, where he became a government researcher… Wang started BYD in 1995 with a $350,000 loan from his cousin. He reasoned he could replace expensive automated Japanese manufacturing systems with one that made use of an abundance of low-cost Chinese workers to assemble batteries manually. But cheap labor was just a piece of the puzzle; the goal was to be as vertically integrated as possible, making not only batteries but also the components, tools and equipment necessary to produce and test them… In 2023, UBS AG did a teardown of the BYD Seal sedan, a challenger to the Tesla Model 3, and found that about 75% of the parts were made in-house, giving BYD a 25% cost advantage over American and European carmakers.

The company got its first big break thanks to a young saleswoman named Li Ke, known outside Chinese-speaking circles as Stella Li. If Wang is the visionary engineer guiding BYD’s elaborate skunkworks, Li, the company’s No. 2, is the driving force behind its expansion, representing BYD in meetings with customers such as Apple Inc. or leaders including the president of Brazil. She graduated from China’s prestigious Fudan University with a degree in statistics and joined BYD in 1996 as a marketing manager for global exports. Wang sent her to Europe and the US to set up offices, and her efforts in that role are the stuff of company lore. In her mid-20s and with a rough grasp of English, Li showed up with a box of battery samples and spent months courting the procurement team at Motorola’s battery R&D campus in the Atlanta suburbs. Motorola executives thought she was a pest, according to one who dealt with her at the time, but the cost savings she was promising were so great and Li was so persistent that they eventually agreed to test BYD’s battery cells. It took two years of evaluation to win the contract. At one point Motorola was so impressed with Li that the company tried to hire her for its sales team…

A year after taking BYD public in 2002, Wang bought a majority stake in a failing state-run car company, Xi’an Qinchuan Auto Co. Angry investors called BYD, appalled that it was wading into a market it knew nothing about—Wang didn’t even know how to drive at the time. But he saw cars as a natural extension of BYD’s battery business. In 2004 he gave a speech at the Beijing auto show declaring his intention to use batteries to change the future of the auto industry. It took almost 20 years for Wang to prove he was right. In 2008, BYD became the first company to produce a plug-in hybrid at commercial scale… Wang continued to pour money into product development, eventually building 11 R&D centers and a vertically integrated company that made everything including batteries, solar panels, printed circuit boards and semiconductors… BYD has equity stakes and long-term agreements with lithium miners, refiners and makers of cathode material, a key battery component…

If the Motorola deal transformed BYD once, the Blade battery, unveiled in 2020—and now powering all of the company’s cars—would do it again. Most researchers outside China were trying to improve EV range by experimenting with nickel-based batteries. Wang chose lithium iron phosphate, or LFP, which was cheaper and less fire-prone but had been largely dismissed because it lacked energy density. Using LFP allowed Wang and his team to streamline the battery pack, do away with some of the clunkier fire-prevention components and fuse cells directly to the chassis. These improvements proved LFP could be harnessed for longer-range EVs, drastically reducing overall cost. It was so competitive that Toyota uses it in its cars in China, as do many Chinese carmakers.

5. One of the great paradoxes of our times is the co-existence of historically high levels of interconnectedness (trade, finance, migration, idea flows, social media etc.) amidst the growing economic, social, political, and geopolitical polarization.

Andy Haldane finds an explanation in the work of Robert Putnam whose book at the turn of the millennium, Bowling Alone, sought to document the weakening of community ethics among Americans since the Second World War. He explained it in terms of the loss of social capital - an erosion of the social networks of trust and relationships and the fraying of the social fabric, within and between communities. Haldane writes ,

Putnam’s recent documentary, Join or Die?, shows that these patterns have worsened over the course of this century — and not just in the US. Unravelling of the social fabric has become an international norm. Research has shown just how large and lasting are the costs of bowling alone. From sub-par growth to stalling social mobility, from the epidemic in loneliness to the crumbling of communities, the erosion of social capital goes a long way to explaining some of our greatest scourges.

He writes about the importance of social capital, compared to the conventional capitals, at individual, community, social, and even national levels.

At the national level, cross-country evidence points towards a strong, causal link between social capital and growth, even once the other “capitals” more often focused on by economists (human, physical and, infrastructure) are taken into account. A 10 percentage point boost in trust raises an economy’s relative economic performance by 1.3-1.5 per cent of GDP. If the UK could achieve Scandinavian levels of trust, this could add £100bn per year to our growth. One key mechanism through which social capital boosts growth is by unlocking opportunity. Recent research by Harvard economist Raj Chetty et al suggests social connectivity may be the single most important determinant of social mobility. Providing a poor (typically disconnected) child with the network of a rich (connected) child boosts their lifetime income prospects by 20 per cent, according to Chetty’s estimates. Few, if any, policy interventions, education or otherwise, yield so high a life-long return.

These effects are just as large and lasting for non-financial measures of health. Century-long US studies tell us that the single best predictor of someone’s longevity and happiness is the quality of their relationships or social capital. As US Surgeon-General Vivek Murthy has observed, bowling alone is the equivalent of smoking 15 cigarettes a day, shortening lifespans and eroding mental health and wellbeing. What is true for individuals and nations is also true for communities. In the poorest, security and solidarity sit at the top of residents’ hierarchy of needs, Maslow-style. Social cohesion and connection are known to reduce crime and antisocial behaviour and build pride in place and belonging. That makes social capital an essential foundation in making successful places. Without it, they atrophy or, worse still, riot. The depletion of social capital matters in one further key dimension — the effectiveness of government. Government legitimacy and effectiveness requires public trust. This is currently in short supply.

Haldane advocates a focused endeavour to develop social cohesion and capital.

Our current education systems are more often a recipe for social stratification than mixing. That calls for a radical rethink of curricula and extracurricular activities, and educational access criteria, to make social connection a fore rather than afterthought. Next, unplanned urban sprawl has contributed significantly to the Balkanisation of communities. In future, social cohesion should be at the heart of spatial planning. LSE professor Richard Sennett has proposed sociable housing, connecting disconnected communities through mixed tenure residences, communal spaces and an improved public realm… Social capital is built on strong social infrastructure — faith-based institutions, youth clubs, community centres, parks, sports and leisure facilities, libraries and museums. Yet investment in social infrastructure is meagre relative to physical and digital infrastructure. Reprioritisation and reinvestment are overdue.

If citizen trust is to be rebuilt, new models of governance are needed too. Citizen panels and juries are effective in building trust and cohesion in diverse communities. Yet they are far from the democratic mainstream. In a return to the original Greek model of democracy, community-led coalitions could play a central role locally. In addition, mainstream and social media are a key conduit for both social connection and, increasingly, social division. Many countries are legislating to avoid online harm. But too little is being done to support online good where it nurtures social cohesion. Public service broadcasters and regulators have a vital role to play in doing so.

No comments:

Post a Comment