I have blogged on several occasions on the world economy’s China problem. This post will examine the more influential views on how countries should respond to the surge in Chinese exports since 2021, described as the Second China Shock (the first being in 2001 after its WTO entry).

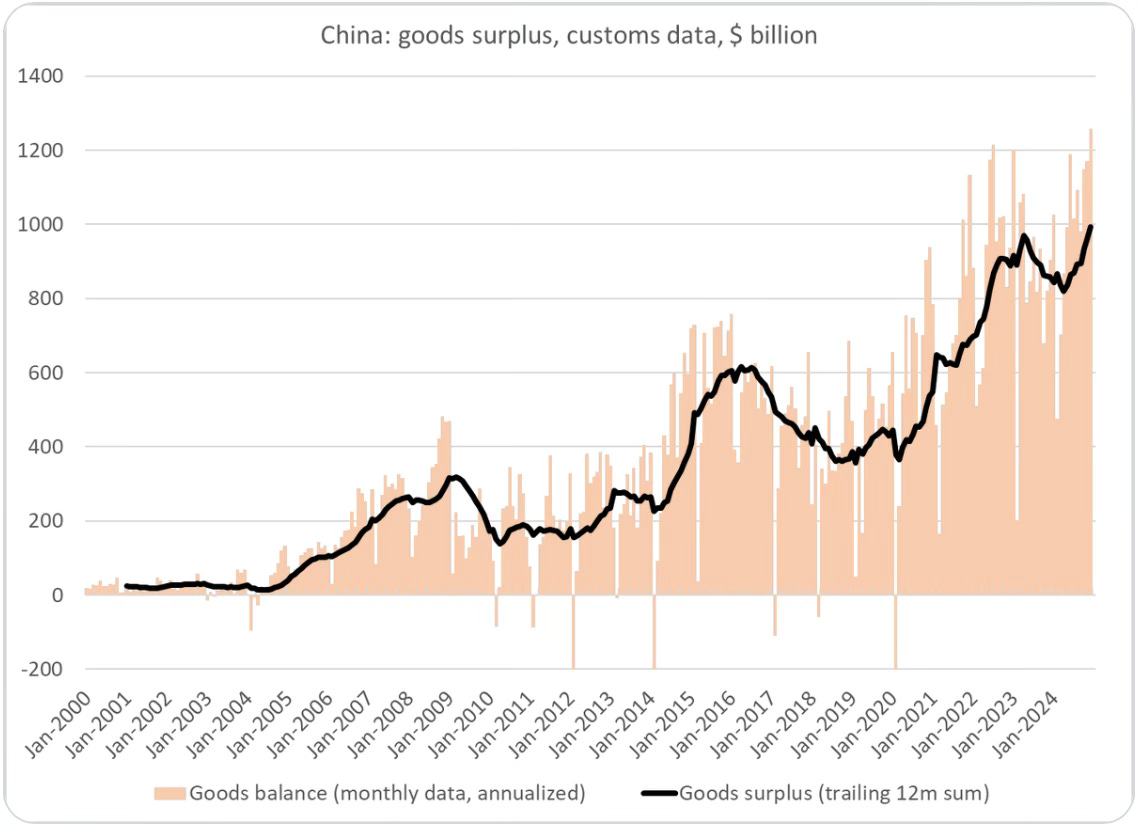

As President Trump assumes charge, it has emerged that China’s trade surplus nearly touched $1 trillion in 2024, a tripling since 2018 when he dramatically surfaced the China problem and made it a bipartisan consensus in the US. His strategy of tariffs and restrictions, while not effectively applied, has since gradually tightened, and the China problem is now acknowledged across countries developed and developing.

Amidst all the growing restrictions and sanctions, China's export engine appears to be motoring ahead at increased speed. After the bursting of the property bubble, since 2021 Beijing has supported a massive expansion of manufacturing capacity. Across sectors, Chinese factory production has been in multiples of what domestic demand would warrant, and the excess capacity is being exported at discounted prices underwritten by heavy subsidies.

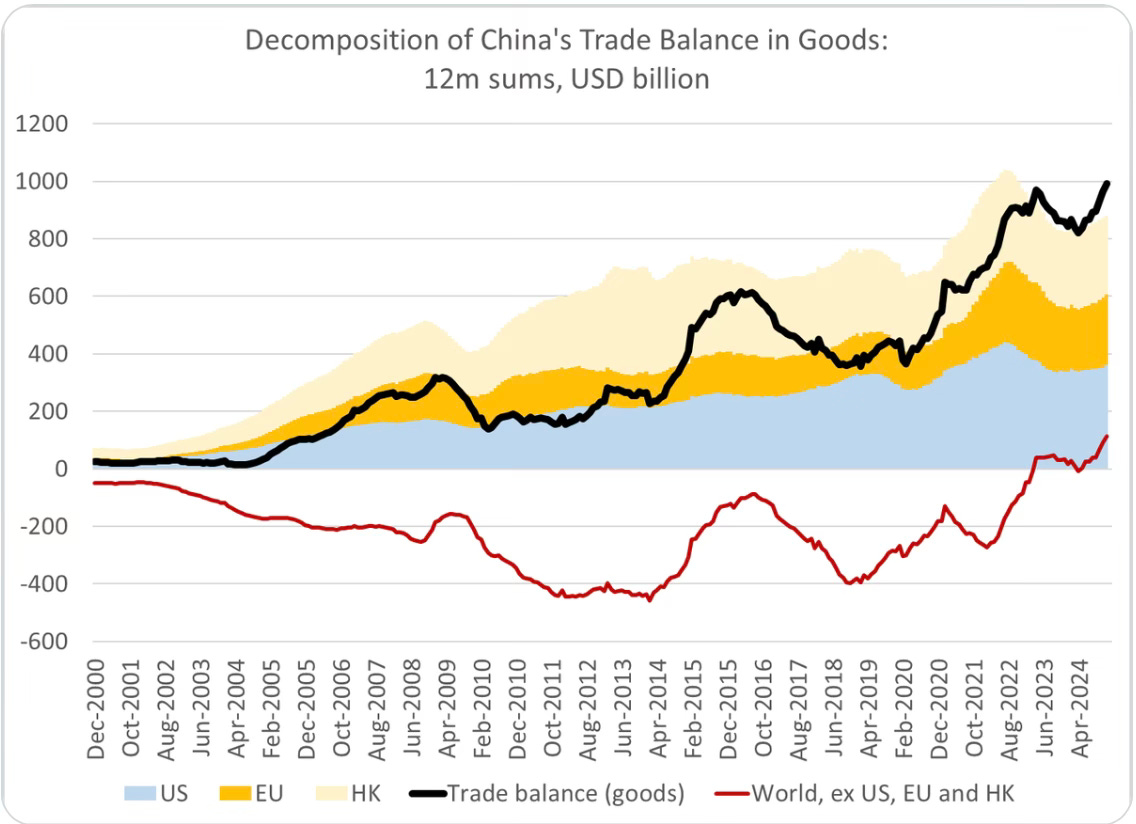

This turbocharging of the Chinese trade surplus has been driven by surging exports to countries other than the EU and the US, a matter that should be of great interest and concern to countries like India.

The NYT has a very good article that puts this in perspective and examines the reasons and consequences.

On Monday, China’s General Administration of Customs said that the country exported $3.58 trillion worth of goods and services last year, while importing $2.59 trillion. The resulting surplus of $990 billion broke China’s previous record, which was $838 billion in 2022. Strong exports in December, including some that may have been rushed to the United States before Mr. Trump can take office and start raising tariffs, propelled China to a new single-month record surplus of $104.8 billion. While China ran a deficit in oil and other natural resources, its trade surplus in manufactured goods represented 10 percent of China’s economy. By comparison, U.S. reliance on trade surpluses in manufactured goods peaked at 6 percent of American output early in World War I, when factories in Europe had mostly stopped exporting and shifted to wartime production...

China has not run a trade deficit since 1993. Its 2024 trade surplus dwarfs earlier records when adjusted for inflation. Japan’s surplus, for example, peaked in 1993 at $96 billion. That works out to $185 billion in today’s dollars, or less than a fifth of China’s surplus last year. Germany ran enormous trade surpluses in the years following Europe’s financial crisis a decade ago. But its surplus peaked in 2017 at a sum equal to $326 billion in today’s money. Japan’s and Germany’s trade surpluses each topped out at about 1 percent of the rest of the world’s economic output. China’s trade surpluses are twice as big by that measure, said Brad Setser, a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations… China now produces about a third of the world’s manufactured goods, according to the United Nations Industrial Development Organization. That is more than the United States, Japan, Germany, South Korea and Britain combined…

China’s exports are booming as its domestic economy is suffering. The trade surplus has offset some of the harm from a housing market crash that has scarred businesses and consumers. Millions of construction workers have lost their jobs, while China’s middle class has lost much of its savings. This has left many families reluctant to spend on either imports or domestic goods and services. Overbuilding of China’s factories has started hurting many Chinese companies, which face falling prices, heavy losses and even loan defaults... Beijing is using its control of China’s state-owned banks to invest excessively in factory capacity. The banks’ net lending to industry was $83 billion in 2019, before the pandemic. That increased to $670 billion by 2023, although the pace slowed somewhat in the first nine months of last year... China has built up its exports through huge investments in education, factories and infrastructure, while maintaining fairly high tariffs and other barriers to imports. Universities churn out more graduates in engineering and related subjects each year than the combined total of graduates in all majors from American colleges and universities…

The backlash to China’s trade imbalance has come from industrialized and developing countries alike. Governments are worried about factory closings and job losses in manufacturing sectors that cannot compete with low prices from China. The European Union and the United States raised tariffs last year on cars from China. But some of the broadest barriers to China’s exports have been put up by less affluent countries with middle-income manufacturing sectors, like Brazil, Turkey, India and Indonesia. They have been on the cusp of industrialization but fear that could slip away. The volume of China’s exports has been rising more than 12 percent a year. The dollar value of its exports has been growing at half that pace, as prices plunged because Chinese companies were producing even more goods than foreign buyers were ready to purchase.

More on this extraordinary manufacturing dominance

Last year, it produced 12.6 times as much steel as the US, 22 times as much cement, and three times as many cars—with whose electric models it now threatens to overwhelm the Japanese and German car markets. China’s shipyards also accounted for over half the ship output. By 2030, China’s manufacturing sector is projected to be bigger than that of the entire Western world. It is already far and away the global leader in every sunrise industry.

Interestingly, the surge in Chinese exports since 2021 can perhaps be partly explained by the depreciation of the renminbi, which on real trade-weighted terms has fallen 15% in the last three years. See also Krugman here.

In fact, even apart from the serious problems engendered by distortions to the economic structure, there are other risks for the Chinese economy. For one, this outsized dominance of the global markets places a prohibitive level of external economic dependence.

The widening of China’s trade surplus accounted for up to half the entire country’s economic growth last year. Investment in new factories for exports represented much of the rest of the growth. In a report scheduled for Friday, China’s government is expected to say that the country’s economy expanded about 5 percent last year.

Or sample this

Citi economists estimated in a research note that a 15 percentage point increase in US tariffs would reduce China’s exports by 6 per cent, knocking a percentage point off GDP growth.

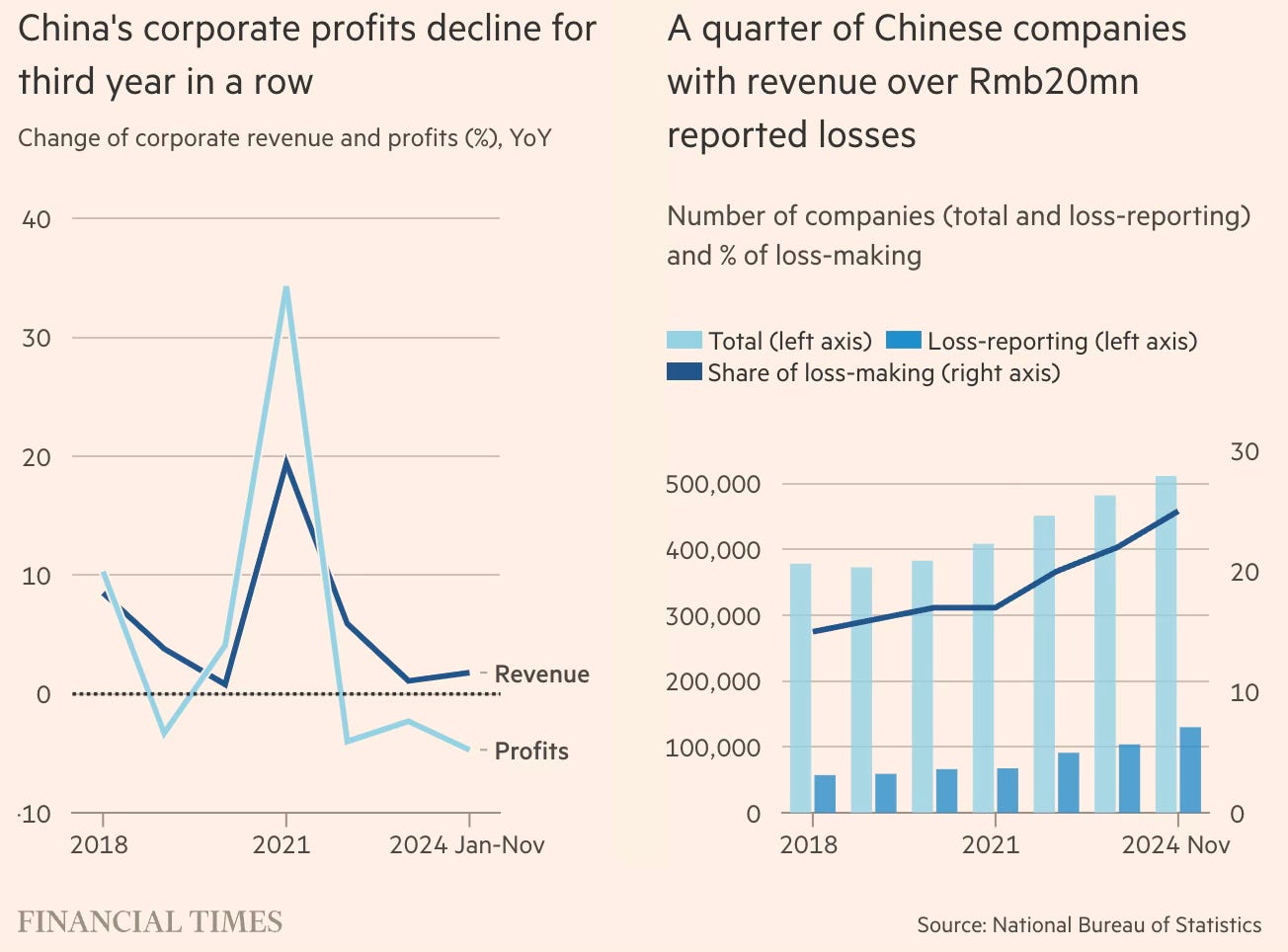

Deflationary pressures are already afoot, and the risks of Japanification loom. Producer prices have declined for 28 months in a row. China’s 10-year bond yields have fallen sharply in recent months to a record low of 1.6%, and the yield curve has shifted downwards at all maturities.

Chinese corporate profits have declined for the third consecutive year.

In addition, 25 per cent of companies in China with revenue of more than Rmb20mn made outright losses between January and November 2024, compared with 16 per cent in the full year of 2019 before the pandemic, NBS data showed. The agency’s data covers 500,000 companies.

So what’s the way out?

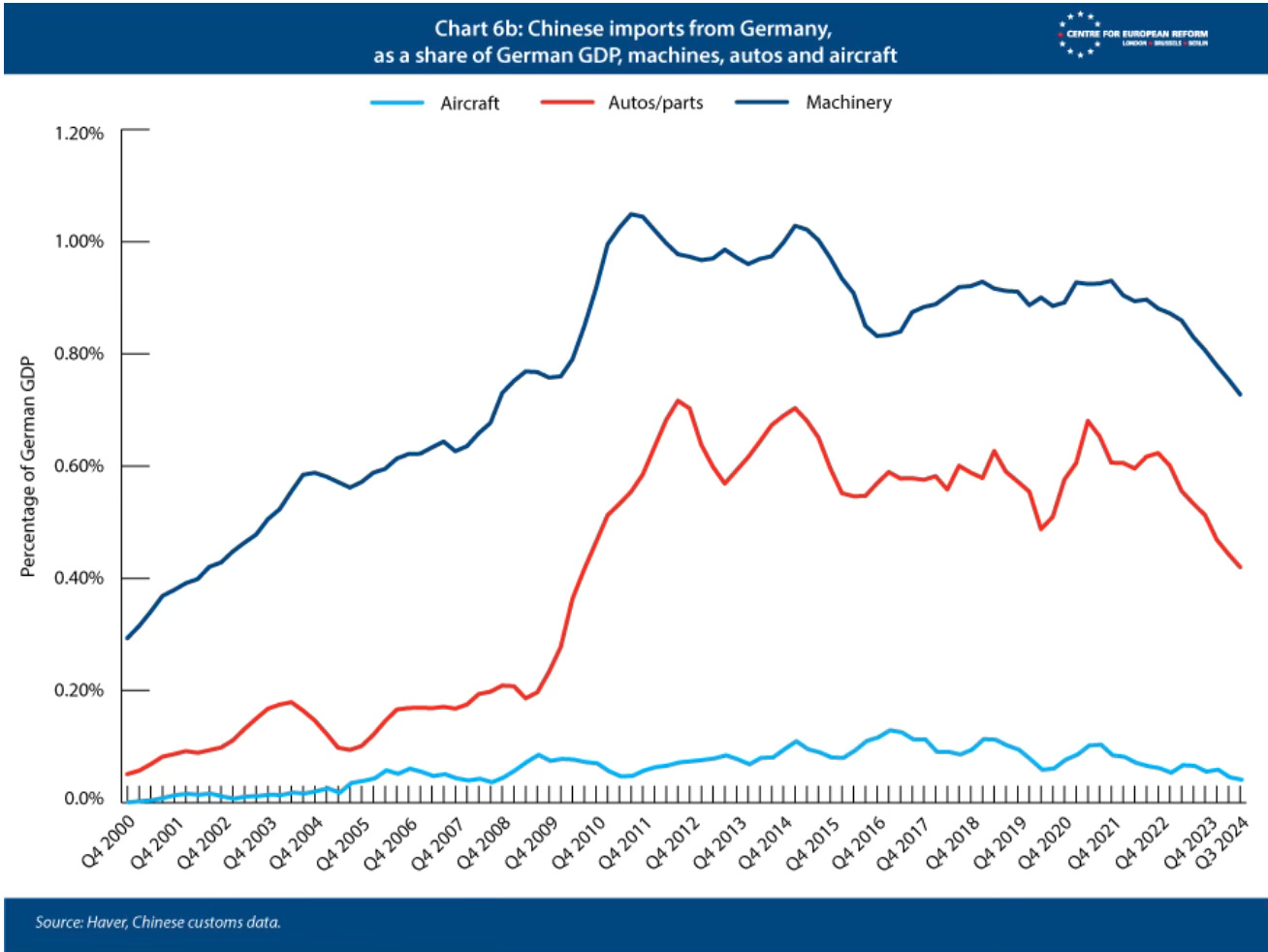

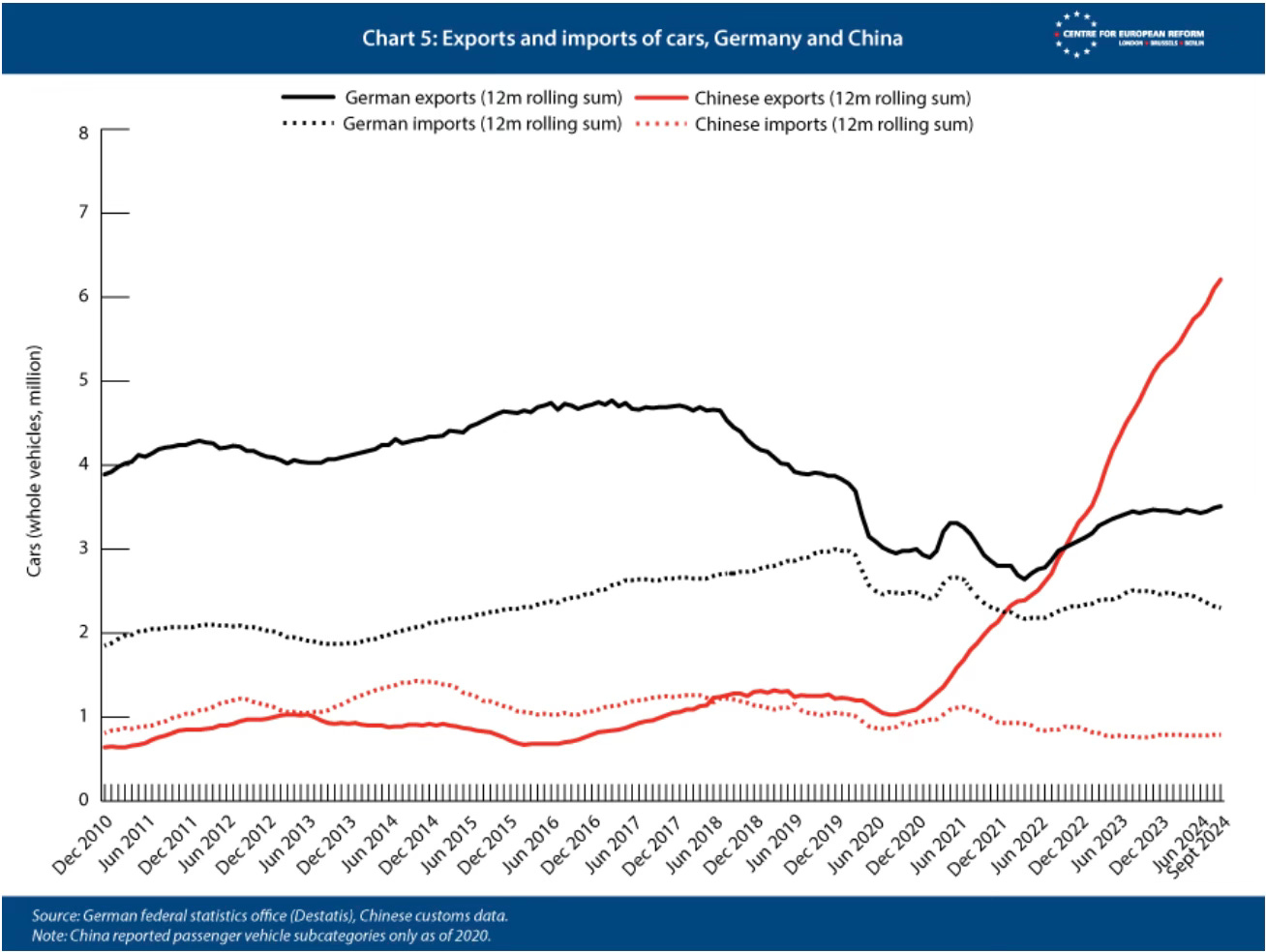

In a new study, Sander Tordoir and Brad Setser (also this X thread) connect Germany’s five-year decline in industrial production and the second consecutive year of economic contraction and China’s trillion-dollar surplus.

Germany is starting to realise that China’s new automotive, clean technology and civil aviation industrial base directly competes with Germany’s manufacturing foundation. China’s macroeconomic imbalances now directly infringe on German industrial interests. Since the property bubble burst in 2021, China has doubled down on directed investment in priority manufacturing sectors, despite a lack of internal demand for much of its output. The result has been a turn back toward export-led growth, with Chinese exports (in volume terms) wildly outperforming global trade in 2024, while German exports in capital and durable goods shrank.

Germany was relatively sheltered from the initial China shock immediately before and after the country’s accession to the World Trade Organisation (WTO) in 2001. Then, China’s exports were in consumer electronics, furniture, apparel and household appliances – not the automotive and engineering sectors at the heart of the German economy. Wage restraint and the cost-savings from expanding supply chains to Central and Eastern Europe created a German competitive export sector able to benefit from Chinese and American demand for machinery. That is no longer the case: China’s economy is much larger; its industry now produces the same goods as Germany and its export-biased growth is cutting into Germany’s European and global export markets.

They propose some policy measures for the German government.

First, Germany should abandon its past opposition to scrutiny of large trade surpluses. It should join the US and the other large G7 economies in encouraging the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to prioritise policies to reduce China’s surplus… Second, Germany should support EU protection of viable European industrial sectors facing an onslaught as a result of China’s active industrial policies. At the same time, it should allow cheap imports in areas where Europe has little to no manufacturing. China’s widespread use of subsidies creates ample scope for WTO-consistent duties, such as the ones the EU pursued for electric vehicles (EVs). Third, Germany and other EU countries should equip existing and new subsidy schemes with de facto buy-European requirements to offset China’s own local content requirements. The EU… can tighten single market regulation (like the Net Zero Industry Act) to ensure EU countries align their national subsidies, for example by linking them to environmental and labour standards which China cannot meet. Fourth, Germany should lead on designing a unified EU industrial policy. Customs income already belongs to the EU and the growing tariff revenue from Europe’s trade defence instruments could be earmarked to fund a common policy.

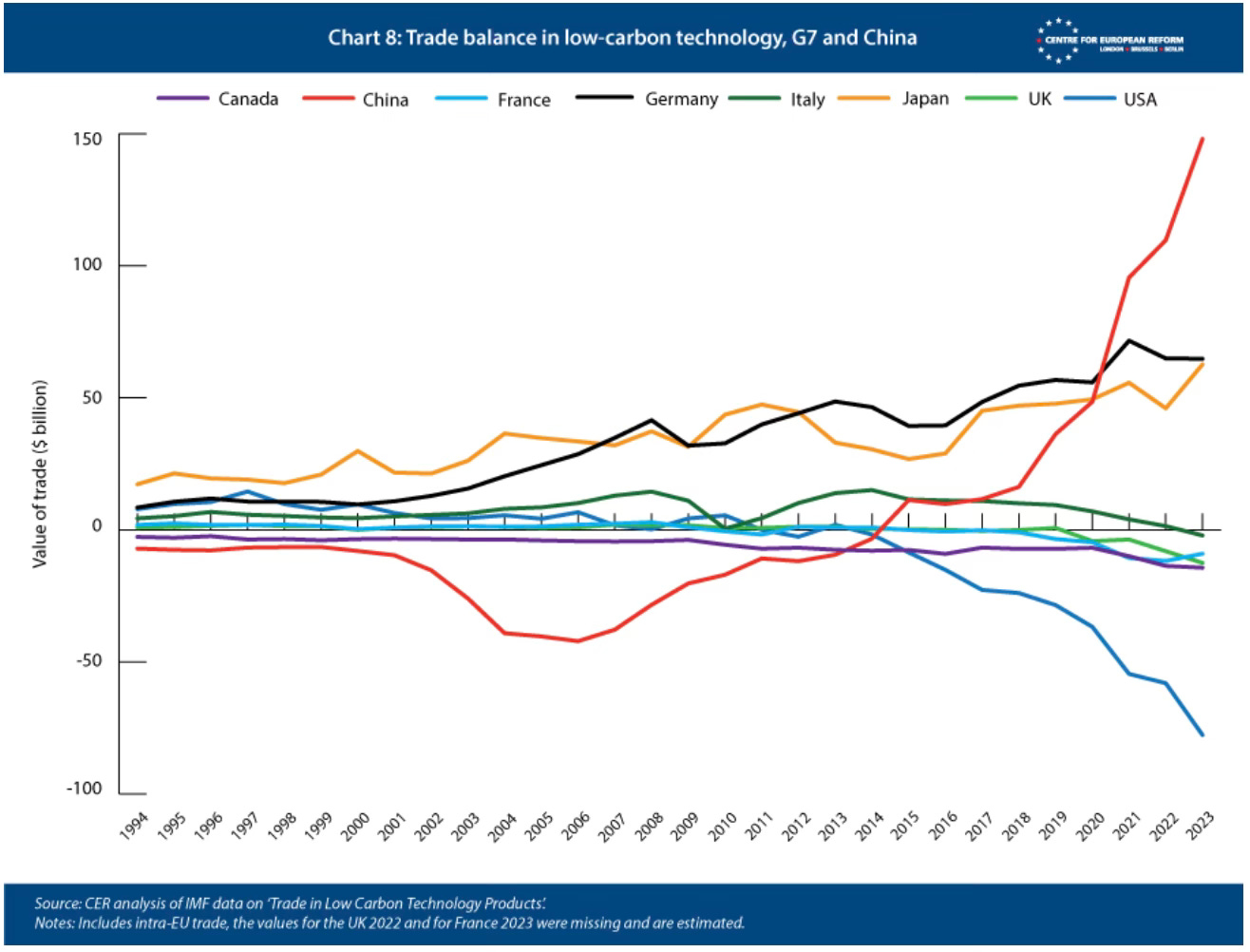

The study has a striking graphic which shows how China has taken the lead in clean technologies with its exports and how the rest of the West (excluding Germany and Japan) are struggling.

In an excellent blog post, Noah Smith channels Michael Pettis who advocates a combination of tariffs by trade partners and structural rebalancing towards domestic consumption by China.

The point Pettis makes is that the US is the global purchaser of last resort, and the low import prices of Chinese goods encourage American consumers to buy more of those products, which, in turn, comes at the cost of American manufacturers and also poses serious national security risks. Given the current situation of Chinese dominance, a reversal of this trend can happen only through tariffs that must also be complemented with measures to revive manufacturing and improve its competitiveness. On the other hand, the only way China can absorb this shrinkage of production (associated with exports) is by boosting its current low level of domestic consumption to channel the domestic manufacturing capacity that’s currently used for exports.

As Noah Smith points out, the export of excess capacity is critical to sustaining economic growth and ensuring the giant investments and production-based Chinese growth model.

Export profits are keeping many Chinese manufacturing companies — and, increasingly, the Chinese economy itself — afloat… China’s export boom is heavily subsidized, both with explicit government subsidies, and — more importantly — with ultra-cheap abundant bank loans. Subsidies are distortionary — they mean that China is making the cars that Germany and Thailand and Indonesia and other countries would be making for themselves if markets were allowed to operate freely. By subsidizing exports on such a massive scale, China is distorting the whole global economy.

And the problems of this strategy are obvious

First of all, if a wave of underpriced Chinese exports forcibly deindustrializes the rest of the world — a possibility I’m sure Xi Jinping has considered — then it could weaken the world’s ability to resist the military power of China and of Chinese proxies like Russia and North Korea… Second of all, even if a bunch of cheap Chinese stuff looks like a gift in the short term, it can create financial imbalances that cause bubbles and crashes in other countries. This is the “savings glut” hypothesis for why the global economy crashed after the First China Shock in the 2000s. And third, a flood of cheap Chinese stuff can cause disruptions and chaos in other economies, hurting lots of workers a lot even as it helps most consumers a little.

It’s in this context that the likes of Pettis argue in favour of tariffs. Noah lays down the theory of change associated with tariffs.

If the world raises tariffs on China high enough, exchange rates will have difficulty adjusting, and Chinese products will have difficulty penetrating foreign markets. Chinese companies will then have to fall back on their domestic market. This will intensify the effect of competition, and reduce their profits much more quickly. The sooner Chinese companies’ profits collapse, they will cut back on production. They’ll also probably pressure the government to stop subsidizing overproduction, in order to lessen the competitive effect and keep themselves in the black. This political pressure could be what finally pushes Xi Jinping and the CCP to change China’s economic model, reducing incentives for overproduction.

This would be good for Chinese consumers. They get a temporary flood of cheap goods when Chinese companies flood the domestic market. If and when China’s government reduced the fiscal and financial incentives for overproduction, China’s taxpayers and savers would get a much-needed reprieve. And in the long run, a less distorted Chinese economy would be good for productivity, since resources would be diverted to sectors that have more room for improvement, like health care and other services.

In this backdrop, it’s worth examining India’s trade challenges. Shankar Acharya helpfully summarises the country’s exports balance sheet in recent times.

In the first dozen years of this century, India’s exports of both goods and services grew strongly. As a share of GDP total exports almost doubled from 13 per cent in 2000-02 to an average of 25 per cent in the three years 2011-14, with the goods share accounting for 17 per cent and services share for 8 per cent of GDP, much of it due to IT-enabled services exports. Since then, the services exports share of GDP has held its ground and then increased to over 9.5 per cent in the last two years. However, the performance of goods exports has been seriously disappointing, with its ratio to GDP falling markedly to around 12 per cent by 2016-17 and languishing at that low level except for a temporary uptick in 2021-23. As a consequence, the share of total exports in GDP was below 22 per cent in 2023-24, as compared to the 25 per cent peak a decade earlier.

India faces several external headwinds that it cannot control - trade distortions (China), trade protectionism (non-tariff barriers), restrictions on security and strategic considerations (telecommunications and frontier technologies), climate adaptation (EU’s CABM). All these trends are most certain to worsen in the time ahead.

It’s therefore important for India to carve out the space within the existing international regimes. Apart from creativity, this also requires a sophisticated understanding of the country’s willingness to tinker with the prevailing trade-related rules and regulations. It must follow the emerging trends globally.

As mentioned earlier, Tordoir and Setser openly advocate not only tariffs and industrial policy measures but also restrictions against Chinese imports. They warn against delaying action.

If it does not act to counter Chinese policies, its current advantages in other sectors will go the same way as those in EV batteries and solar panels… the EU should target its scarce industrial policy funds to maximise European competitiveness. This means supporting value chains (and regions) with strong potential, many of which are centred in Germany. Germany would be a primary beneficiary of a significant European funding programme for decarbonising industry or expanding chip production, for example.

They make the important and clear distinction and divergence between corporate interests and national interest, and urge Germany to act in its national interest.

Berlin frets that a more muscular EU industrial and trade policy would lead to Chinese retaliation against German multinationals operating in China. But a new German government should not equate the interests of German businesses operating in China with the interests of the German economy. What is good for Volkswagen is no longer always what is good for Germany. It would not be in Germany’s long-term interest, for example, if German firms turned China into their hub for the design and production of all luxury EVs, eroding the technical skill set and advanced quality production of cars that has long been the mark of the German economy. For German workers the trade-offs are stark and real; German firms that succeed by moving production of cutting-edge technologies out of Germany ultimately weaken, rather than strengthen, the German economy.

In short, across the developed world, textbook theories on free trade are being discarded in favour of policies that not only directly promote domestic industry but also penalise Chinese and foreign manufacturers. Academic experts and others who peddle orthodoxy are being marginalised everywhere. Pettis captures this mood nicely

If you want to understand the effects of trade intervention, its ok to ask economic historians, but never ask economists. That's because their answer will almost certainly reflect little more than their ideological position. Depending on their ideology, they will either only explain how trade intervention affects consumers (it lowers the consumption share of GDP) or how it affects producers (it raises the production share of GDP). They will never explain that it matters to both.

This is a great X-thread from Pettis on economists and free-trade.

This is a reminder for India to be cautious about embracing the opinions and comments of economists and experts on tariffs, joining free trade agreements and so on. In fact, in a 2016 survey of academic economists, not a single respondent agreed with the idea of putting tariffs to encourage domestic production.

Given the circumstances and the policies pursued by others in their national interests, there’s a need for India to take a strategic view on these issues. The two largest economies flagrantly violate the provisions of WTO and the third, EU, does so with finesse.

China has been using industrial policy to build up capacity across industries that are multiples of domestic demand and is discounting and exporting their production. This Kiel Institute paper documents its subsidies for green technologies and this CSIS study examines its general industrial policy subsidies. Its economy-wide practices of providing land, utilities, and credit at concessional rates tilt the playing field in favour of its exports and have distorted global trade.

The US has shown little interest in even the existence of WTO, and this is certain to be accentuated in the next four years. The IRA Act and CHIPS Act, for example, both enacted by the supposedly multilateralist Biden Administration, have several provisions that fly against the WTO Agreements. The EU (and also the US) resort to non-tariff barriers (NTBs) that tend to have the effect of making Indian exporters ineligible or uncompetitive in public procurements and from general markets.

The case for India joining FTAs, as advocated by several economists and experts, while good in theory, does not pass the test of evidence. Ajay Srivastava of GTRI has explained with evidence that India’s FTAs with ASEAN, Japan, and South Korea, all signed in 2010-11, have not proved beneficial to India. India’s high existing tariffs, compared to the very low tariffs of its trade partners, mean that any FTA would inherently benefit its partners much more than India. Besides, Indian exporters face non-tariff barriers - environment, sustainability, labour, intellectual property rights, digital trade, governance, and gender - whose compliance is prohibitive.

In light of such practices that are now becoming pervasive, the problem statement for India should be about creating the external space to shape its industrial policy to promote its national interests without being perceived as an egregious violator of its multilateral commitments (like the US or China). How can India subsidise its domestic manufacturers and incentivise exports, or differentiate incentives between domestic consumption and export while also maintaining a fig leaf of compliance with WTO Agreements? This ought to be our strategy on trade and WTO.

There’s a practical problem in the pursuit of this strategy. From the perspective of bureaucrats in the different line Ministries, it’s perfectly reasonable to examine every policy from the narrow view of its compliance with the WTO regulations that concern their Ministry. There are several examples of narrow perspectives coming in the way of India pursuing policies that are in the national interest.

It’s not as if India has not pursued such policies earlier. An example is the use of domestic content requirements to access subsidies and other incentives. For example, the Jawaharlal Nehru National Solar Mission, launched in January 2010, contained domestic content requirements to avail of its incentives. These measures violate Article III:4 of GATT 1994, Article 2.1 of the TRIMS Agreement and several provisions of the WTO’s Subsidies and Countervailing Measures Agreement. Notwithstanding this, there are numerous examples of its violations by India itself and others. Incidentally, in July 2023, India and the US withdrew their respective complaints against each other pending before the WTO’s DSB on subsidies and domestic content requirements. In fact, domestic content requirements have now almost become a norm in the industrial policies of developed countries.

Notwithstanding the WTO, it’s, therefore, time for India to take a leaf out of the playbooks of the Americans, Chinese and Europeans and design policies that promote its national interest through the likes of incorporation of domestic content requirements and supporting exporters with concessional credit and other incentives. It’s all the more relevant now that President Trump, who prefers the transactional approach (Art of the Deal), takes office for the second time. India could embrace the strategy of ‘appeal into the void’ and strike bilateral deals with its contesting trade partners.

No comments:

Post a Comment