One of the most disturbing economic trends of our time is that of technological advances automating work and displacing labour. While in its early stages, there are compelling reasons to believe that unlike with earlier technologies, robots and automation could significantly shrink the labour market.

This, by itself, should be a matter of deep concern. But this trend also adversely impacts labour’s bargaining power with capital, thereby creating the conditions for worsening the already stark inequities in the sharing of capital returns.

The prevailing incentives and power relations of the market, left to itself, will invariably encourage firms to deepen and accelerate the adoption of labour-minimising technologies. This market failure will necessitate public policy action.

A recent FT long read examined the impact of the strike last October by some 25,000 members of the International Longshoremen’s Association (ILA) that grounded three dozen container ports on the US east and Gulf coasts, which handle one-quarter of the country’s international trade and cost the economy up to $4.5 bn a day. The strike was withdrawn after just 72 hours following negotiations and an offer of a salary increase of nearly 62% over six years.

But, as the FT article points out, the main issue goes beyond salaries and is existential for workers.

Although it was the pay rise that caught the attention of the media, the union’s real issue is with automation — specifically proposals by the United States Maritime Alliance (USMX), which represents port operators and container carriers, to equip more US ports with semi-automated cranes. These cranes are equipped with advanced technology that makes them faster and more efficient to operate, say the owners. But the ILA claims that their introduction threatens their members’ livelihoods. Unless USMX agrees to a total ban on automated machinery, the union has threatened to strike again as early as next week. “We embrace technologies that improve safety and efficiency,” the ILA’s colourful president, Harold Daggett, said in a statement. “But only when a human being remains at the helm.”

… As more and more businesses experiment with next-generation robotics, US labour unions representing industries as varied as UPS drivers, Las Vegas casino workers and grocery store employees are fighting for provisions to be added to contracts that focus on retaining jobs and compensating displaced workers in the event of automation. What were previously run-of-the-mill negotiations over pay and conditions have mushroomed into larger, more existential disputes over the relationship between humans and machines… Whatever contract the longshoremen negotiate, say analysts, could help provide a template for agreements nationwide.

Turbocharged by the advances in artificial intelligence, robots are being experimented across sectors.

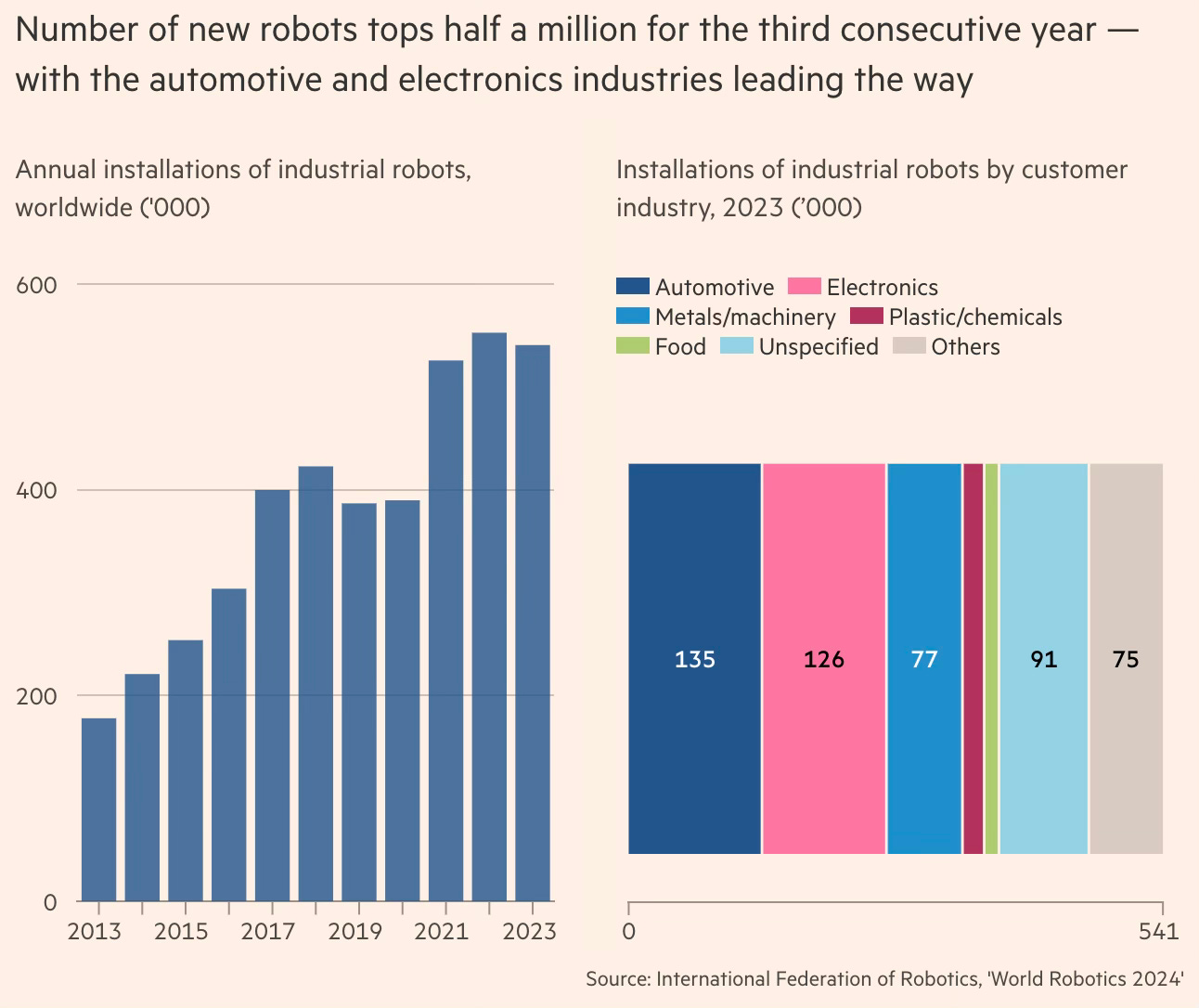

Since General Motors first put robots on assembly lines in the 1960s, carmakers have been pioneers in automation. Yet until the rise of AI, other industries — ones requiring more dexterous tasks, or where robots might need to respond to unpredictable or hazardous environments — struggled to follow suit… Manufacturing companies in particular have invested heavily, with total installations of industrial robots rising by 12 per cent to over 44,000 units in 2023 — the largest volume in at least a decade, according to the International Federation of Robotics. Again, the car industry has led the way, followed by electrical and electronics companies…

On their annual trip to the Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas last year, members of the Culinary Union, which represents staff at casinos in the city, were shocked to see robots frying food and making cocktails… In 2022, real estate developer The Durst Organization’s venture arm invested in the maker of a glass-washing robot, Skyline Robotics, based in Israel. The Ozmo robot can now be seen scrubbing the windows of a skyscraper near Times Square… “It’s very understandable to me why that next generation isn’t showing up,” says Skyline Robotics president Ross Blum. “It is a really tough job . . . Who wants to go hang 1,000 feet in the air today and do manual labour outdoors?”

Worsening the problem is the challenges associated with labour market adjustments arising from automation.

MIT economist Daron Acemoglu says that robots’ current capabilities mean that those most at risk of being displaced are in blue-collar jobs and lack college degrees, which may make it difficult for them to shift into the high-tech roles likely to be created by automation.

Consider the market forces at play that have driven the search for labour-saving technologies

Jobs that looked like they could only be done by people suddenly look risky; economists have warned of wholesale and disruptive changes to the workforce as machines are capable of more and more… Adding to the pressure in economies like the US, say business owners, is sluggish growth in the labour force, which is making it increasingly hard to recruit workers. President-elect Donald Trump’s plans for mass deportations… will probably only intensify such concerns… Salary increases experienced by many Americans in the past few years have come at a cost… it makes the US somewhat uncompetitive… As the population ages and families struggle to find childcare, the share of Americans in work or seeking work has been declining for decades — dropping from 67.3 per cent in 2000 to 62.5 per cent late last year. Economists estimate that it will sink to 60.4 per cent by 2030.

US investors have piled more than $15bn into robotics start-ups since 2019, according to PitchBook, and the remarkable growth of artificial intelligence in the past 18 months has begun to show dividends… US venture capital investment in robotics has risen from around $2bn in 2019 to more than $3.5bn last year, according to data from PitchBook. In the first nine months of 2024, there were 130 fundraising deals for robotics start-ups — more than across the entirety of 2019. Among the most high-profile was a $675mn investment last February by Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, Microsoft and Nvidia in Figure AI, a Silicon Valley start-up founded in 2022 that is working on a faceless, humanoid “general-purpose” robot. It said that month that these robots — whose cost to customers is estimated at between $30,000 and $150,000 — could complete tasks including moving a box on to a conveyor belt, potentially endangering the job of anyone working in, say, a distribution centre. The first models were delivered to a “commercial client” last month.

The article points to the ILA’s concern at containerisation being a case of once bitten twice shy.

Before the advent of containerisation, longshoremen spent long days unloading individual boxes, barrels and crates, then transferring their contents on to trucks and freight trains — dangerous but reliable, well-paid work that, at its peak, employed an estimated 100,000 men in ports around the US. After the trucking entrepreneur Malcom McLean championed the 8ft-wide steel container in the mid-1950s, that world fell away. The new technology meant that cargo could be transferred with a minimum of effort and drastically reduced costs. Tens of thousands of jobs disappeared almost overnight. Despite a huge increase in world exports, the number of longshoremen employed at the Port of New York and New Jersey plummeted from 55,000 in the 1950s to about 4,000 today, says Jean-Paul Rodrigue, a professor of maritime business at Texas A&M University…

When semi-automated cranes were first brought in to terminals on the east coast of the US in the early 2000s, ILA leaders say they agreed to the changes because it would help create jobs. But they now say that the opposite happened… A 2022 survey commissioned by the west coast dockworkers’ union found that partial automation of the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach resulted in the loss of nearly 1,200 jobs in 2020 and 2021. USMX says that because most of the ports its members operate have no spare land available, the only choice is to “densify terminals” by adding machinery that speeds up operations. In a conventional crane, an operator sits inside a cab, lifting containers off ships and sorting them, before transferring them to trucks or trains — a highly skilled job that can earn workers as much as $200,000 annually. In a semi-automated rail-mounted gantry crane (RMG) system, the operator works remotely from an off-site office, monitoring the crane via video link but letting the system do most of the work. The job requires similar skills and training, but fewer people are required… But USMX describes calls to ban automation as “unworkable”, saying that modern crane technology has “nearly doubled” both the throughput of containers and the number of workers at the ports using it.

So how is labour adjusting to the emerging trends?

In recent years, both retail and culinary unions have negotiated clauses in contracts they hope will protect human workers. Las Vegas casinos are now required to give people six months’ notice before implementing new technologies and free training on how to use them, plus severance packages for anyone laid off because of technology. UPS has agreed to negotiate with the Teamsters, one of the most powerful unions in the US, before introducing drones or driverless pick-up vehicles. New York retail stores whose workers are represented by RWDSU, including Bloomingdale’s and Macy’s, also require management to come to an agreement before introducing new technologies.

This has relevance to developing countries like India.

The adoption of labour-saving technologies by companies in developing countries is likely to lag behind those in developed countries. This is a good thing. Given the abundance of cheap labour, the economic case for automation has limits. Further, the vast informal sector, with its deeply price-sensitive consumers, too is unlikely to be disrupted significantly.

However, the pace of adoption will be significantly higher in those sectors competing globally and among the biggest firms, which are also the creators of good-paying jobs. Consider AI-based automation displacing lower and middle-level software jobs, which comprise the vast majority of well-paying services sector jobs. Or the automation of assembly lines in textiles, footwear, electronics, consumer durables, automotive etc., which make up the vast majority of well-paying manufacturing jobs. The disruption in the former can be immediate and more gradual in the latter.

In other words, in developing country contexts, the biggest adverse impact of labour displacing technologies is likely to be in the large layer of good jobs that pay reasonably well at the entry and middle levels. They are the lifeboats to enter the middle class.

If this trend starts to surface, it’ll invariably trigger a backlash and create the conditions for populist narratives, with all their risks of distortions and perversions. It’s therefore important that governments realise the strong likelihood of such developments and calibrate policies in this direction.

Accordingly, there’s an increasingly strong case to align industrial policy to both encourage job-creating economic activities and also discourage the adoption of labour-saving practices and technologies. While the former has always been a salient feature of industrial policy, it’s now time for the adoption of the latter.

This would entail shifting away from capital investments that lead to automation towards labour subsidies. The PM Internship Scheme, if scaled up in a realistic manner, is the right kind of policy for the times. As an illustration, a Rs 100 Cr capex subsidy is equivalent to providing 50% of the salary for five years for 1250 workers with a starting cost to the company of around Rs 22000 and increasing annually at 10%. At a more realistic 33% and 3 years, the same labour subsidy can employ nearly 3500 workers. This can be a significant incentive for businesses and an entry point for a better life for blue-collar entrants.

Such industrial policy could discourage assembly line automation in manufacturing. Similarly, it should be examined as to whether tax policies can be carefully tweaked to encourage software companies to develop business models that can accommodate the displaced manpower in other activities/areas. Taxation policies that incentivise manufacturing and R&D should be revisited to keep these challenges in mind.

From the labour market side, there will be demands to institutionalise as policy mandates the protections being negotiated in the US by labour unions. I’m not sure about its advisability.

Such policies can create perverse incentives, and administering them can be hard. It’s therefore essential to be flexible with them.

But they cannot be ignored for too long given the scarcity of good jobs for a rapidly growing pool of labour market entrants, and the strong likelihood of brewing discontent spilling over into some form of undesirable populist backlash.

No comments:

Post a Comment