The country has become a solar champion thanks to abundant sunshine and the government’s pro-renewables policies. But a surge in power production has outpaced demand, depressing electricity prices and profits for generators. Some power producers are struggling to offload plants whose valuations have plunged as executives talk of solar “saturation”... Operational solar plants were valued at an average of €916,000 per megawatt in early 2024, but have now dropped to €648,000 per megawatt, according to nTeaser.... the gloom is even greater over so-called ready-to-build projects, where land, permits and grid access have all been secured, but construction has not begun. A senior executive at an owner of Spanish solar plants said: “The market is flooded with ready-to-build projects that developers want to sell since they’re no longer good enough in the current market.” Some projects were up for sale for just €1, the executive said, reflecting developers’ desperation to avoid further spending, and potential government penalties for not executing agreed construction plans. The least attractive ready-to-build projects are often far from power grid nodes, requiring investment in expensive power lines.... low prices are painful for producers. When they fall below zero, as they have for more than 500 hours in Spain this year, producers can end up having to choose between paying wholesale customers to take excess power off their hands or switching off. Many producers insulate themselves by selling electricity through long-term power purchase agreements (PPAs), which they sign at fixed prices with corporate clients for 10-20 years... Adding battery storage to solar plants helps to limit price plunges by enabling generators to store electricity when prices drop during the day, then sell it in the evening when demand and prices are higher.

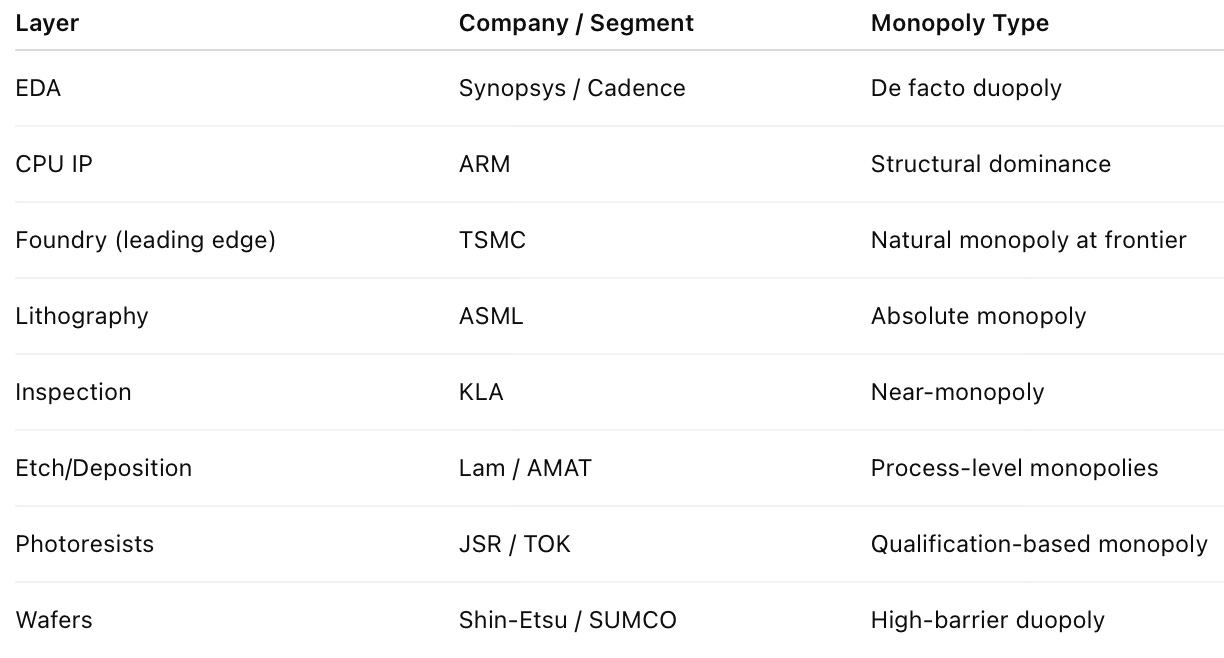

38 per cent of undergraduates at Stanford this year are registered as having a disability, as are 21 per cent at Harvard — both up from 5 per cent in 2009... The bulk of the rise in special support for youngsters is cases of non-profound autism spectrum disorder (ASD), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) plus anxiety and mental health, all of which have flexible diagnostic criteria… we consistently see mild, not severe, cases driving the rise... As the number of more mild cases receiving support has climbed over the past decade, average funding per child (including the most severe cases) has fallen by a third in real terms… In 2010, 1 per cent of American young people from the poorest school districts were on plans that provide special support, and today that figure is unchanged. But among those in the richest areas, it has tripled from 2 to 6 per cent.4. The Big 5 Indian IT firms have added just 17 net workers in the first three quarters of Fy26!

China’s decline in private final consumption expenditure is in sharp contrast to consumption-dependent economies like the United States (US) and India, with their share of private final consumption reaching 68.39 per cent (in 2022) and 61.38 per cent (in 2024) of their GDP, respectively. Among the top five economies of the world, China has the least share of private final consumption in its GDP. On the contrary, China has the highest share of fixed investment in its GDP – almost 10 percentage points higher than India’s share. Further, China has the largest share of net exports, after the EU.

8. The biggest trade promotion policy ever? The shipping container.

Nothing has done more to juice global trade than a simple receptacle—spanning about 40 feet on the long side and eight on the other two. It could be stuffed with cargo and hoisted onto lorries, trains, ships or planes with equal ease. That humble steel box—the standard shipping container—did “more than all trade agreements in the past 50 years put together” to boost globalisation

9. The US government has announced a $1.6 billion investment in USA Rare Earth, a listed Oklahoma-based miner that controls significant US deposits of heavy rare earths.

One person said the government would get 16.1m shares in USA Rare Earth and warrants for another 17.6m, both at a price of $17.17. The government agreed to pay $277mn for the equity, giving it an implied gain of $490mn for the equity and warrants based on the current share price of $24.77. USA Rare Earth will also receive $1.3bn in senior secured debt financing at market rates from the government. The money will come from a finance facility created for the commerce department as part of the CHIPS and Science Act passed in 2022... A condition of the government investment in USA Rare Earth was that the company raise at least an additional $500mn from investors. It is on track to raise more than $1bn because of high demand for the financing deal, which uses a mechanism known as a private investment into a public equity, often called a “Pipe”...USA Rare Earth, which has a market value of $3.7bn, is developing a huge mine in Sierra Blanca, Texas that it says contains 15 of the 17 rare earth elements underpinning production of cell phones, missiles and fighter jets. It also plans to open a magnet production facility in Stillwater, Oklahoma... Last year, the Trump administration invested in at least six minerals companies, including MP Materials, Trilogy Metals and Lithium Americas. Some of the investments overlapped with the financial interests of people associated with the administration. The government did a funding deal with Vulcan Elements, a rare earths start-up three months after the president’s son Donald Trump Jr’s venture capital group invested in the company... USA Rare Earth has separately tapped Cantor Fitzgerald, the Wall Street firm previously owned by commerce secretary Howard Lutnick and now run by his sons, to raise more than $1bn in fresh equity financing, the people said.

10. President Trump has announced his intention to cap credit card interest rates at 10% and has enlisted the services of an unlikely partner, Elizabeth Warren, to draft legislation in this regard.

But a study by Liberty Street Economics found that spreads are high across all levels of credit ratings measured by so-called Fico scores and that default losses cannot explain the huge spreads above FFR... A recent Vanderbilt study concludes that at a 10 per cent cap, banks could continue profitably serving the vast majority of their customers... Americans pay about $160bn a year in credit card interest.

Sheila Bair, the former FDIC Chair, has this alternative proposal.

A better approach would be a permanent cap expressed as a spread over the FFR, say 10 per cent. This would be consistent with pre-crisis spreads. It would ensure that banks pass on the benefits when the Fed lowers rates but also allow them to raise rates when the FFR goes up. At the current FFR, it would bring credit card rates to just under 14 per cent.

11. Debashis Basu on the challenges with tripling exports by 2035, a CAGR of 13%. From history, South Korea increased its exports by a CAGR of around 18% between 1965-85, Taiwan by 16% in the 1965-80 period, Thailand by 14% in 1986-96, Malaysia by 14% in the 1987-2000 period, and Vietnam by 14% from 2005-24.

History suggests that sustaining export growth of around 13 per cent for a decade requires these conditions: Cheap currency, strong central coordination and disciplined policy execution, a large surplus of labour at low wages, assured access to large and open markets, and a willingness to tolerate overcapacity and frequent failures. India currently possesses none of these in sufficient measure. Instead, it faces headwinds from rising protectionism, aggressive dumping by China, and reforms that are often procedural rather than outcome-oriented.

12. The non-profit only mandate for schools in India is among the biggest charades.

India’s rules continue to insist that most private schools are “charities”. The result is a system that makes it hard to bring capital in openly or take returns out transparently. Founders instead resort to legal gymnastics. A single school is often split into three entities: a trust to hold recognition and collect fees; a land company to own the campus; and a services firm to run everything from transport to maintenance. Three entities mean three sets of books, audits, and compliance calendars. Even routine decisions, like paying salaries or upgrading infrastructure, require cross-entity coordination that adds weeks of delay. Hanging over all this is the lingering uncertainty of the government suddenly cracking down on the school or changing a rule about the trust... Every rupee that leaves the account must be defensible on paper. Salaries are routed as lease payments to a land-owning entity and as service fees to an operating company. Each transaction is vetted by his chartered accountant, ensuring no regulator can later accuse the school of making a profit—before it has even run payroll.

The arrangement is captured nicely here.

In the current year, the central government’s gross borrowing is pegged at Rs 14.72 trillion, and net of redemptions, the net borrowings, at Rs 11.54 trillion... The gross SDL in the current year is Rs 11.83 trillion... Will there be demand for such a large borrowing programme? That’s the challenge before the RBI. In the current year, it has managed this by buying bonds from the market, popularly known as open market operations, or OMO. In FY26, a record Rs 6.45 trillion (till February 12) is being raised through this route, more than double of what the RBI had bought in FY25. The highest OMO before this was in FY21 – a little over Rs 3.13 trillion...Until the global financial crisis of 2008, the central government’s gross borrowing never crossed Rs 2 trillion. And SDLs were much lower – in thousands (for instance, Rs 20,825 crore in FY07). In FY09, the central government’s gross borrowing crossed Rs 2 trillion for the first time. The following year, it jumped to over Rs 4 trillion. The next big jump came in the Covid-hit FY21. From a little over Rs 7 trillion in the previous fiscal year, it rose to Rs 13.7 trillion that year. It crossed Rs 15 trillion in FY24, and is now set to cross Rs 16 trillion in FY27. Though the size of borrowing has increased over the years, as a percentage to GDP, it has remained largely in range... But SDL is becoming a burden. Before the global financial crisis, state loans were just 15-20 per cent of central borrowing every year. In FY27, these could be 75-80 per cent; and over the next few years, SDL may even exceed the centre’s annual borrowing. The oversupply of SDL has widened the spread between the yield of 10-year central government and state government papers to 85 basis points. Typically, it is about 40-50 basis points.

14. China is enhancing state capability by recruiting more tax officers to strengthen enforcement amid widening budget deficits.

Central and local government tax departments plan to recruit 25,004 staff in 2026, accounting for two-thirds of the new bureaucrats to be appointed from among the millions taking part in fiercely competitive national exams, according to the state civil service administration. The plans mark a fourth successive year of heavy recruitment of tax officials, with the number of appointments set to marginally exceed a previous peak of 24,985 in 2023 to reach the highest level since at least 2012… Tax authorities have also announced moves to tighten tax enforcement and to scale back the use of corporate tax breaks by local governments… Authorities are also broadening the tax base by capturing more high-income earners, including those making capital gains on offshore equity investments… China’s tax revenues have fluctuated in recent years and fell 3.4 per cent year on year to Rmb17.5tn ($2.5tn) in 2024.15. The rise and rise of Gold.

Housing accounts for 18 per cent of employment, making it the second-largest generator of jobs. It has deep linkages with more than 250 ancillary industries, creating powerful multiplier effects. Every investment in a housing unit generates 1.54 direct and indirect jobs and 4.05 induced jobs — much higher than employment multipliers in agriculture (0.8 and 1.2)... The average loan-to-value (LTV) ratio is a mere 65 per cent, compelling homebuyers to rely on other expensive borrowing sources for interiors and registration... less than 8 per cent of loan originations have an LTV greater than 80 per cent... even in a relatively safe asset class like mortgages, more than 75 per cent of lending is still to “prime” borrowers (bureau scores of 730 and above). The likelihood of a “near-prime” borrower (bureau score 650-700) getting a loan approval is just 40 per cent... housing finance to GDP ratio at 11-12 per cent is much lower than comparable economies.

17. What explains the weakness in East Asian currencies despite these countries running large surpluses, the general weakening of the US Dollar, and the smallest interest rate spread with the US in years?

Under the deal, Indian levies on EU cars will be gradually reduced from 110 per cent to 10 per cent, with a quota of 250,000 vehicles a year. Tariffs of up to 44 per cent on machinery, 22 per cent on chemicals and 11 per cent on pharmaceuticals will be mostly eliminated. Steel and iron levies of up to 22 per cent will also be phased out over a 10-year period... Tariffs of more than 36 per cent on EU food products will be reduced or removed, the bloc said, while those on wine will be slashed from 150 per cent to 75 per cent and eventually to levels as low as 20 per cent. Olive oil tariffs will also fall from 45 per cent to zero over five years. Those on processed agricultural products, such as bread and confectionery, of up to 50 per cent will be eliminated. In exchange, more than 99 per cent of Indian exports, worth about $75bn, will gain preferential entry status to the EU... The Indian dairy industry, a politically important constituency that New Delhi has sought to protect in the past, was excluded from the deal. Sensitive EU agricultural sectors, such as beef, chicken, rice, sugar and ethanol, were also carved out.