1. Case study of US toy maker, Learning Resources, on the challenge of diversifying away from China.

While you can move your manufacturing out of China, it’s much harder to move China out of your manufacturing.

Some snippets highlighting the point above.

The toymaker offers about 2,000 products; a few years ago more than 80% of them were produced in China by companies that tapped into the country’s countless vendors of plastic resins, paint pigments, computer boards and other materials... China has about 10,000 toy manufacturers, versus roughly 100 factories in Vietnam skilled enough to produce for export... This lack of scale means less competition to bring down prices, crucial for toys, where margins typically stand in the single digits. Learning Resources is moving batches of about two dozen products at a time to Vietnam, a time-consuming and costly process. Each toy requires as many as a half-dozen heavy steel molds, which are mostly made in China. Ruffman estimates it will cost about $5,000 to move each mold to Vietnam—adding millions of dollars in expenses that contribute nothing to the bottom line... Vietnam’s output per employee is as much as 40% lower. That’s because Chinese factories have invested heavily in automation and can rely on an experienced workforce... China’s combination of expertise and infrastructure “doesn’t exist anywhere else”.

2. Avocado farming comes to India. It can generate annual income of about Rs 4 lakh per acre, net of all expenses.

Currently, demand within India is met largely by imports which are doubling every year. In FY24, India imported 5,040 tonnes which climbed to nearly 12,000 tonnes in FY25. This year, the imports are likely to cross 20,000 tonnes (the imports during the first quarter of FY26 was nearly 7,400 tonnes). Come to think of it, a few years back, in FY21, imports were a mere 234 tonnes... Despite the growing popularity of avocados among farmers, it’s only the well-off who are getting into it. The reason is simple: for orchards to yield a remunerative return, it takes 4-5 years from planting. The costs range from ₹4-5 lakh per acre (apart from the land cost). Just one sapling of avocado can cost anywhere between ₹800 to ₹2,500 (about 150 saplings can be planted in an acre) depending on the variety and rootstock... As per a June 2025 estimate from Rabobank, the global avocado market is around $20.5 billion. The report estimated that global avocado exports are likely to touch 3 million tonnes by 2026-27, from one million tonnes in 2012-13. Today, India imports about 90% of the avocados it consumes from Tanzania (as the produce is duty free), with smaller volumes coming from Australia and Kenya, among others.

3. For all the talk of China competing with the US on AI, the latter dominates VC funding in the field.

And AI computing power too is concentrated in the USFor about two decades up to the pandemic, Chinese demand for German engineering goods and cars was seemingly insatiable, fuelling the Merkel-era growth in corporate profits, employment and economic activity. Since the pandemic, however, China is “increasingly beating Germany at its own game”, says Spyros Andreopoulos, founder of Frankfurt-based consulting firm Thin Ice Macroeconomics. On average, Chinese capital goods are 30 per cent cheaper than those of Europeans. Crucially, manufacturers in the Asian superpower have also closed the quality gap. Since the start of 2025, Germany is now running a trade deficit in capital goods with China over a rolling 12-month period. That is a first since records began in 2008. Chinese machinery exports to Europe roughly doubled to around €40bn in over six years and may reach €50bn this year, according to industry association VDMA. While German premium car brands like Audi, Porsche and Mercedes-Benz were the first to feel the pain, capital goods makers have started to get similarly pounded...Goods coming out of China are no longer cheaply made, lower-quality knock-offs, if they ever were... When it comes to speed, they have surpassed Western rivals by a mile, needing half the time to turn a new idea into a finished product. Shorter product cycles mean quicker learning... Philipp Bayat, chair of Munich-based compressor maker Bauer Kompressoren Group, gives a striking example. He needs a new wire-processing machine for one of Bauer’s European plants. A quote from a Swiss-based European company stands at €130,000, compared with one from a firm based in China’s Zhejiang province for less than €28,000.

4. Sander Tordoir makes the case for Buy European policy to counter the rising imports of Chinese automobiles that threaten to destroy Europe's automotive industry.

Europe’s car industry employs more than 10 million people and accounts for a larger share of private R&D spending than any other industry... Thanks to widespread subsidisation and genuine innovation, China’s global car exports are exploding, and European exports are being squeezed out of global export markets, starting with China. EU car exports to the United States (US) almost doubled between 2019 and 2024, but President Trump’s 15 per cent tariffs and his rollback of EV subsidies will deal another blow. EU domestic demand, meanwhile, is weak... Rather than tampering with regulations, EU policy-makers should ensure that demand from Europe’s huge single market, with 450 million consumers and a vast corporate sector, spurs European production. That primarily means supporting demand through consumer subsidies, with a buy-European clause co-ordinated across member-states...To align demand-support schemes across the EU, the Union should Europeanise the French eco-bonus. The French model, with its carbon-based scoring system, is the most practical template to adopt across member-states. It effectively steers demand toward European-made EVs and filters out Chinese production, because it limits subsidy to EV models produced in low-emission supply chains... To support its car sector, Germany has just committed to reintroducing EV subsidies. Equipping them with the eco-bonus would align Germany with France and support a buy-European policy. Italy and Spain, which are reviewing their subsidies next year, could then follow suit...Household EV purchases backed by subsidies would cover only 40 per cent of the total European car market. Over 60 per cent of EU new registrations are company cars which already benefit from sizeable subsidies. Support schemes for corporate EVs should also be conditional on European content requirements. Ensuring that buy-European subsidies apply to both markets would also allow Germany to secure demand for premium models, common in corporate car fleets, while France, Spain and Italy gain scale in the smaller cars which are more common in the household market... because buy-European clauses would be open to producers across the EU, the policy would not require policy-makers to pick ‘winners’. German tax incentives would also help French producers, and vice versa. A harmonised EU framework could avoid subsidy fragmentation, foster competition in the European market, and level the playing field with China, which excludes foreign vehicles from its own subsidy schemes.

5. Top Chinese companies are training their AI models overseas to skirt the US ban on the sale of Nvidia chips.

Alibaba and ByteDance are among the tech groups training their latest large language models in data centres across south-east Asia... there had been a steady increase in training in offshore locations after the Trump administration moved in April to restrict sales of the H20, Nvidia’s China-only semiconductors... Over the past year, Alibaba’s Qwen and ByteDance’s Doubao models have become among the top-performing LLMs worldwide. Qwen has also become widely adopted outside China by developers as it is a freely available “open” model.Data centre clusters have boomed in Singapore and Malaysia, fuelled by Chinese demand. Many of these data centres are equipped with high-end Nvidia products, similar to those used by US Big Tech groups to train LLMs. According to those familiar with the practice, Chinese companies typically sign a lease agreement to use overseas data centres owned and operated by non-Chinese entities. This is compliant with US export controls as the Biden-era “diffusion rule” designed to close this loophole was scrapped by US President Donald Trump earlier this year.

6. This is important for China to remember as tensions between it and Japan rise.

“The more pressure China exerts on Japan, the more Japan feels compelled to prepare, recognizing the growing danger — Prime Minister Takaichi’s approval ratings are rising, and the Japanese people’s sense of crisis is also increasing,” said Ichiro Korogi, a professor of international studies at Kanda University of International Studies.

7. Is there anything China wants to import from rest of the world?

There is nothing that China wants to import, nothing it does not believe it can make better and cheaper, nothing for which it wants to rely on foreigners a single day longer than it has to. For now, to be sure, China is still a customer for semiconductors, software, commercial aircraft and the most sophisticated kinds of production machinery. But it is a customer like a resident doctor is a student. China is developing all of these goods. Soon it will make them, and export them, itself. “Well, how can you blame us,” the conversation usually continued, after agreeing on China’s desire for self-sufficiency, “when you see how the US uses export controls as a weapon to contain us and keep us down? You need to understand the deep sense of insecurity that China feels.” That is reasonable enough and blame does not come into it. But it leads to the following point, which I put to my interlocutors and put to you now: if China does not want to buy anything from us in trade, then how can we trade with China?

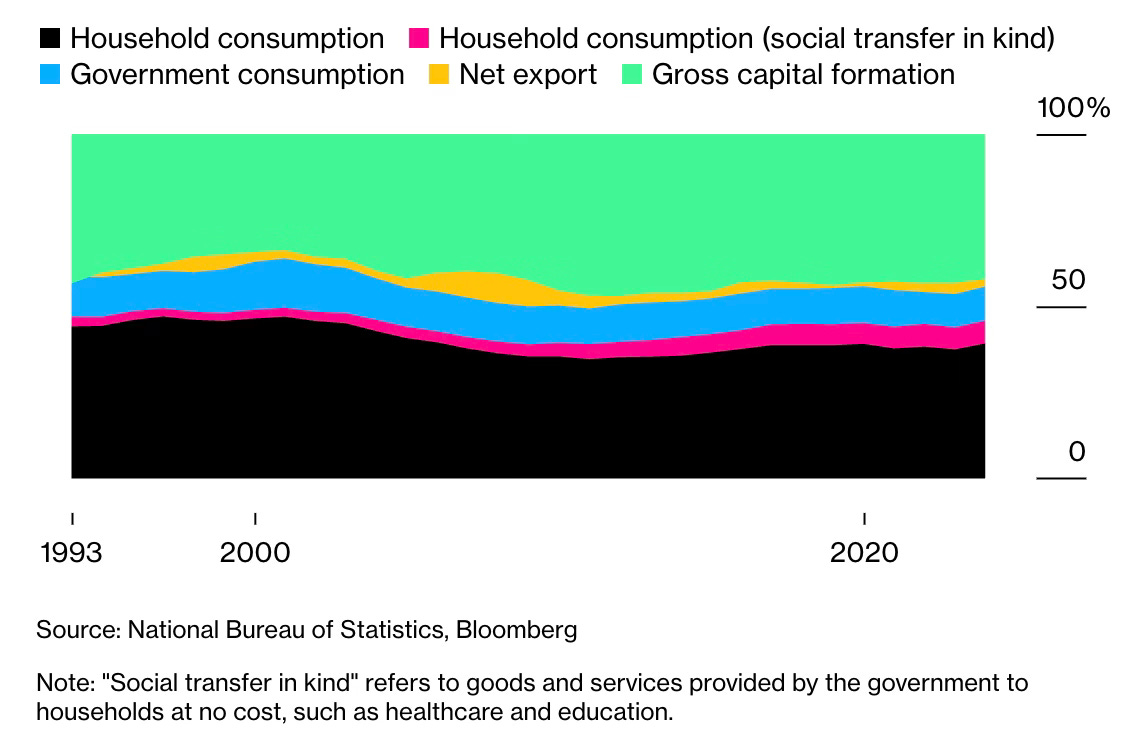

In the circumstances, what can China do?

Beijing could take action to overcome deflation in its own economy, to remove structural barriers to domestic consumption, to let its exchange rate appreciate and to halt the billions in subsidies and loans it directs towards industry. That would be good for the Chinese people, too, whose living standards are sacrificed to make the country more competitive.

8. Europe's CBAM makes India's steel less competitive compared to China's.

Over one-third of India’s 6.4mn metric tonnes of annual steel exports go to Europe, which will implement its divisive carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM) on January 1, a tax on polluting overseas producers aimed at protecting EU industry from being undercut by cheaper but dirtier imports. India’s European exports are expected to be disproportionately affected by the new rules, with Chinese steel imports subjected to an average tariff of 7.75 per cent compared with India’s 16 per cent levy, according to the Net Zero Industrial Policy Lab at Johns Hopkins University... India is “less efficient” compared with other major steel-producing nations, with an emissions intensity of 2.5 tonnes of CO₂ per tonne of crude steel compared with the global average of 1.9 tonnes.

9. The rise of psychiatric disorders in the US is disturbing.

A diagnosis of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder is practically a rite of passage in American boyhood, with nearly one in four 17-year-old boys bearing the diagnosis. The numbers have only gone up, and vertiginously: One million more children were diagnosed with A.D.H.D. in 2022 than in 2016. The numbers on autism are so shocking that they are worth repeating. In the early 1980s, one in 2,500 children had an autism diagnosis. That figure is now one in 31. Nearly 32 percent of adolescents have been diagnosed at some point with anxiety; the median age of “onset” is 6 years old. More than one in 10 adolescents have experienced a major depressive disorder, according to some estimates.

10. Alan Beattie calls peak Trump tariffs, even as affordability and cost of living become a rising issue in US politics.

The meeting in October with Chinese President Xi Jinping, in which Trump backed down after threatening a massive escalation of tariffs, now looks a lot like an inflection point. Last week, having remained composed in the face of Trumpian invective against the criminal prosecution of his coup-fomenting predecessor, Brazil’s President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, was rewarded with massive cuts in US tariffs on food. Fellow Central and South American countries Argentina, Ecuador, Guatemala and El Salvador got similar relief, and so probably will the EU. Canada has yet to be clobbered with the additional 10 per cent tariffs Trump threatened for the heinous crime of accurately quoting Ronald Reagan in a TV ad. Reports suggest he will soften or shelve forthcoming tariffs on semiconductors.

Gillian Tett writes

Four months ago, US President Donald Trump announced 40 per cent additional tariffs on Brazilian imports (creating 50 per cent total levies), because he was furious about the country’s legal investigation into Jair Bolsonaro, its former president, and its clampdown on US Big Tech. But President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva defiantly hit back at the bullying — boosting his domestic popularity — and defended the courts. A Brazilian judge has now sent Bolsonaro to jail. And those tariffs? Last week, Trump declared that “certain agricultural imports from Brazil should no longer be subject to the additional [40 per cent surcharge]”. In plain English: Lula won.

India remains the only country to have not benefited from the Trump retreat.