At the heart of the AI investment boom are data centres. This post examines some of the issues associated with them, specifically their financing models and their energy demand.

The emergence of AI models and applications for inference has resulted in a surge in demand for data centres with high-performance supercomputers. The extent of investments required for these data centres has been described as “one of the biggest capital movements in history.”

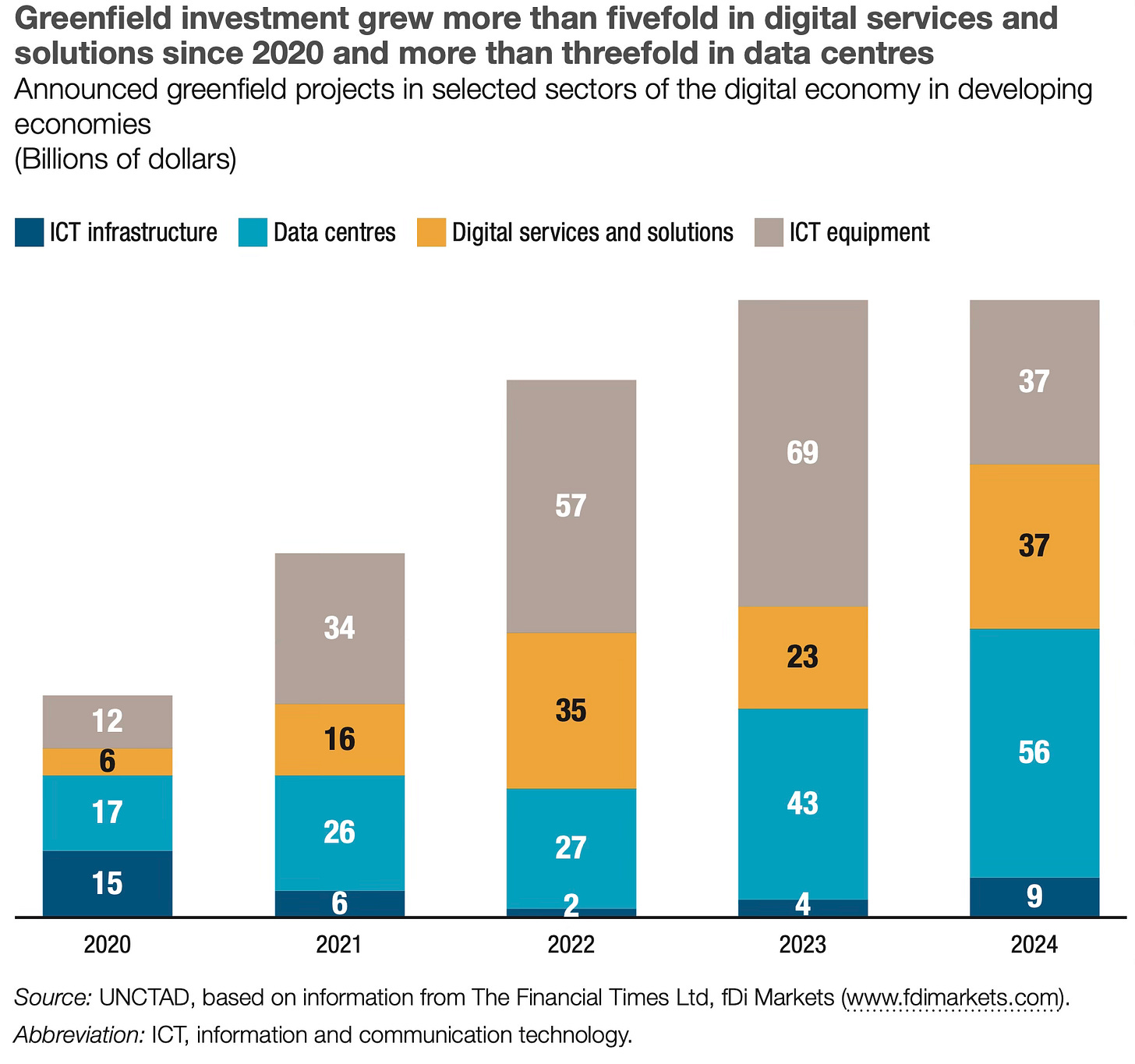

It’s estimated that the US has about 20 GW of operational data centre capacity, and another 10 GW is projected to break ground in 2025, of which 7GW will be completed. Globally, too, data centre investments are booming, including in developing countries. The World Investment Report 2025 shows that greenfield investments into data centres in developing countries more than tripled between 2020-24 to $56 bn.

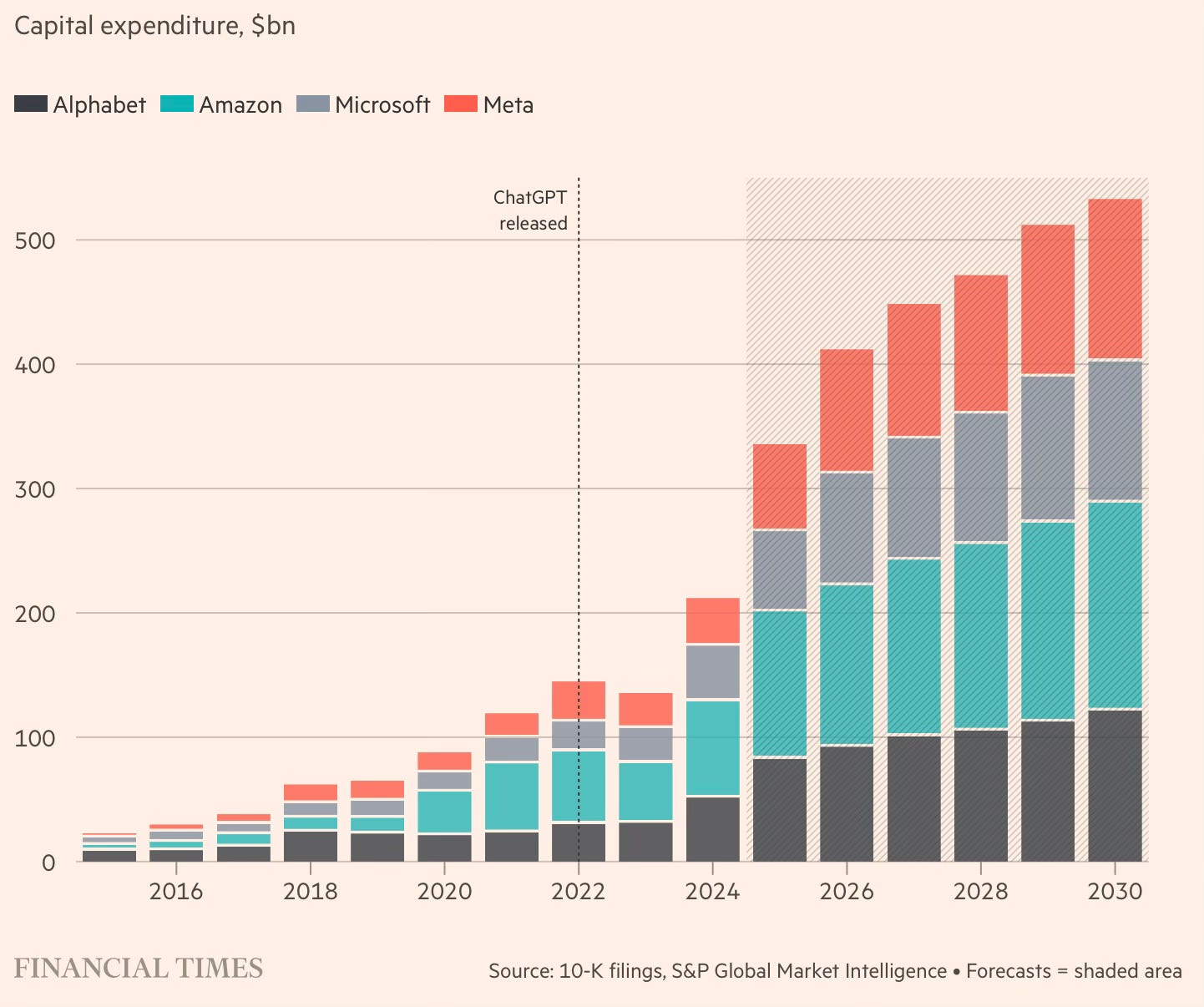

Technology companies are investing heavily in AI-related hardware as they race to harvest the potential benefits from the promising general-purpose technology and conquer the emerging market.

The scale of capex by the big US tech companies — Microsoft, Alphabet, Amazon, Apple and Meta — is staggering… Their collective investment splurge amounts to arguably the biggest, and certainly the fastest, infrastructure rollout in history. Arete Research estimates that these companies will spend about $480bn in capex in the next two years, much of it on the 100 data centres they are currently building. Many of those data centres will be powered by Nvidia’s GPUs.

The company at the centre of this investment boom is OpenAI. With a flurry of deals, the loss-making owner of ChatGPT, with an annual revenue of just $13 billion but over 700 million regular users of its blockbuster chatbot, has signed broad agreements with SoftBank, Oracle, and Nvidia for capital spending of $1 trillion. Even if only a tenth of these commitments materialise, it would be the largest set of corporate investments in a single company in history.

Nvidia’s CEO Jensen Huang has said that every 1 GW of data centre capacity requires $50 billion of spending on computing hardware, including Nvidia’s GPU processors and networking technology and server racks produced by the likes of Foxconn, HP, Dell, etc. Nvidia’s $100 billion investment in OpenAI alone is estimated to require 10GW of data centre capacity, enough to power 10 million typical US households. Morgan Stanley has estimated that deploying 10GW of AI computing power could cost as much as $600bn, of which $350bn “potentially” goes to Nvidia. Similarly, Stargate’s $400 billion investment is expected to require 7 GW of data centre capacity. In fact, OpenAI’s Sam Altman has writtenthat he wants to add 1 GW of new AI infrastructure every week.

The vast majority of these investments would go into building data centres to train and run inferences on OpenAI’s ML algorithms. These data centres, in turn, would run the algorithms using Nvidia’s latest generation of GPU chips and Oracle’s cloud infrastructure.

The deals also highlight companies scrambling to mitigate risks through several innovative emerging models of financing the AI infrastructure. OpenAI itself is buying data centres, cloud infrastructure, and GPU chips through long-term capacity purchase commitments with their respective developers and producers. Under these unique arrangements, the latter would “invest equity” in OpenAI by offering their assets to it to train and run its algorithms.

The staggering sums involved in these announcements have naturally raised questions.

Who will be on the hook for the data centres built in the hope that AI demand will continue to boom, and where will the cash flow come from to support the mountains of debt that are sure to be involved? How likely is it that OpenAI’s business will support the $300bn in cloud payments it is due to pay Oracle by 2030, or that Nvidia will see the $350bn-$400bn in new chip sales that analysts project from its OpenAI deal?

How would Oracle, already debt-ridden, raise the resources to build the data centres? Would SoftBank find investors willing to assume the massive risks and cough up the amounts it has committed?

Fundamentally, AI input suppliers (like Nvidia and Oracle) are betting on the expectation of a spectacular boom in the demand for OpenAI’s algorithms. Similarly, financiers like SoftBank see this as the big emerging opportunity. This carries the risk of becoming the mother of all Ponzi schemes if the demand does not materialise.

Highlighting the risks, a report by Bain has estimated that AI companies need to spend $500 bn annually till 2030 on capital investment to meet anticipated demand. This can be justified only with annual revenues of $2 trillion, which it says the industry will miss by nearly $800 billion.

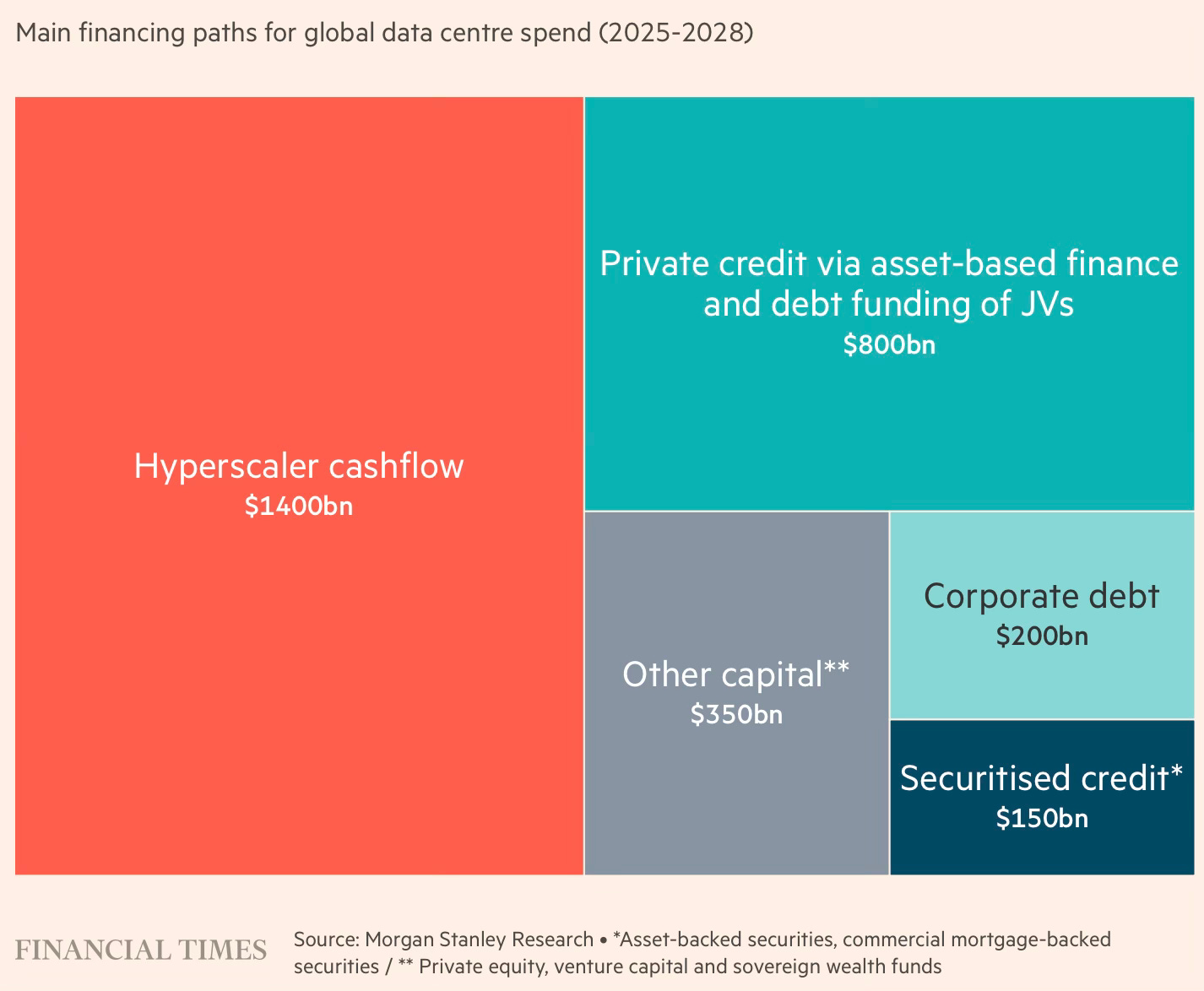

In recognition of these risks, as investments in data centres grow exponentially, instead of financing from internal reserves, the hyperscaler firms (AWS, Azure, and Google Cloud) are turning towards structured finance mechanisms to expand the envelope of capital and also ensure more efficient sharing of risks.

Between now and 2029, however, global spending on data centres will hit almost $3tn, according to Morgan Stanley analysts. Of that, just $1.4tn is forecast to come from capital expenditure by Big Tech groups, leaving a mammoth $1.5tn of financing required from investors and developers. The gap will be filled by everything from private equity, venture capital and sovereign wealth to bank loans, publicly listed debt and private credit. But increasingly, the answer is debt… Funding data centres comes not just with the risk that costs overrun, but also that the technology becomes obsolete far quicker than anticipated, requiring new investment that decreases returns for its owner — or forces them to sell at a discount. That means even the deepest-pocketed tech groups may want to share the risk, particularly when debt is cheap and readily available. Deals are being structured in myriad different ways, from structured debt solutions and project finance vehicles to construction loans, asset-backed securitisations and even green bonds to raise money and start building.

Morgan Stanley has estimated global spending on data centres to be $2.9 trillion by 2029, of which only $1.4 billion is expected to come from the Big Tech groups and $1.5 billion is expected from investors and developers.

The financing sources include structured debt solutions, project finance, construction loans, asset-backed securitisation, green bonds, etc. For financial intermediaries like private equity that are struggling in the face of high interest rates and the absence of exits, data centres are emerging as the new big opportunity. They could also be a major driver of the growth of private credit.

Essentially, data centre financing models are increasingly shifting from data centre developer firms raising debt against their land and project assets, towards more complex structured financing. They involve primarily long-term capacity commitments and/or land leases by AI algorithm users like the hyperscalers, against which developers raise a combination of equity and debt financing. Input suppliers, such as Nvidia (GPU chips), OpenAI (ML algorithms), and Oracle (cloud infrastructure), agree to share risks by forgoing upfront payments on their products and solutions. This approach diversifies risks among all stakeholders.

This investment frenzy stands amidst the deep uncertainty about the likely scale of commercial returns of AI-related applications.

There are wildly different views about how quickly such applications will be adopted and what their economic impact will be. In a much-discussed paper from Goldman Sachs, the MIT economist Daron Acemoglu made a powerful case that the likely benefits of AI would be a lot smaller than investors assumed and would take much longer to realise. In the meantime, there was an asymmetric risk that the technology’s downsides, such as deep fakes, might arrive quicker than the rewards. Acemoglu forecast that AI would only boost US productivity by about 0.5 per cent and GDP by around 1 per cent over the next decade. That is dramatically lower than Goldman’s predictions of 9 per cent and 6.1 per cent, respectively. If Acemoglu’s analysis is correct, the US stock market — including Nvidia — is heading for a messy reckoning.

Notwithstanding the hyperscalers’ generative AI revenues of just $45 billion in 2024 despite the already large investments made on AI models, the prospect of a winner-takes-all market means that the Big Tech firms are unwilling to hold back.

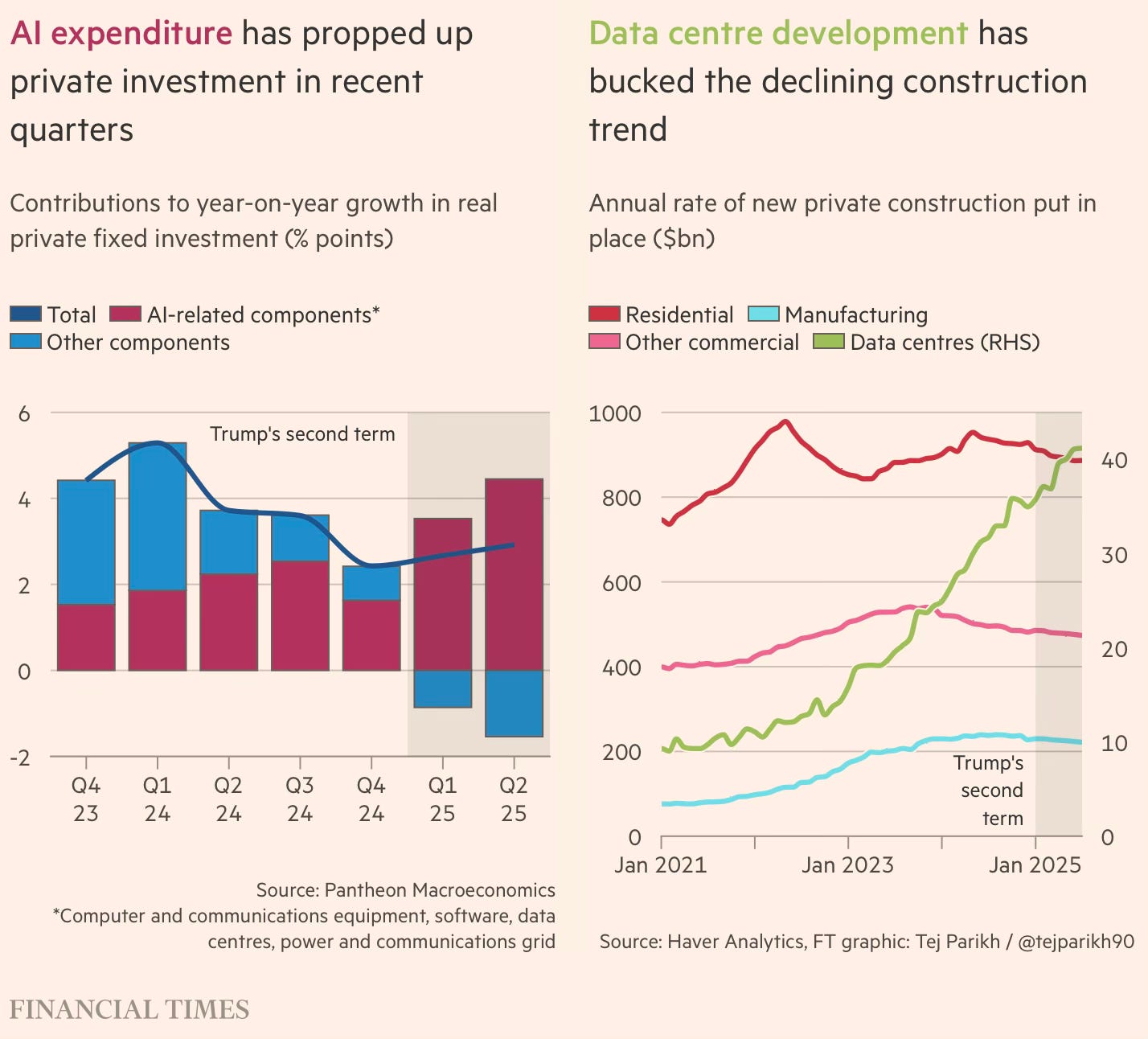

The surge in AI-related investments is now having economy-wide effects in the US. There’s now enough evidence that the AI frenzy is a bubble, and boosting growth in the US economy in an unhealthy manner. In the US, even as private investment has generally tanked due to higher interest rates and rising uncertainty, AI expenditure has propped it up. In fact, but for AI-related spending, the total private fixed investment growth of 3% in the second quarter would have fallen by 1.5%. And even as data centre construction has boomed, residential, manufacturing, and other commercial building work have declined.

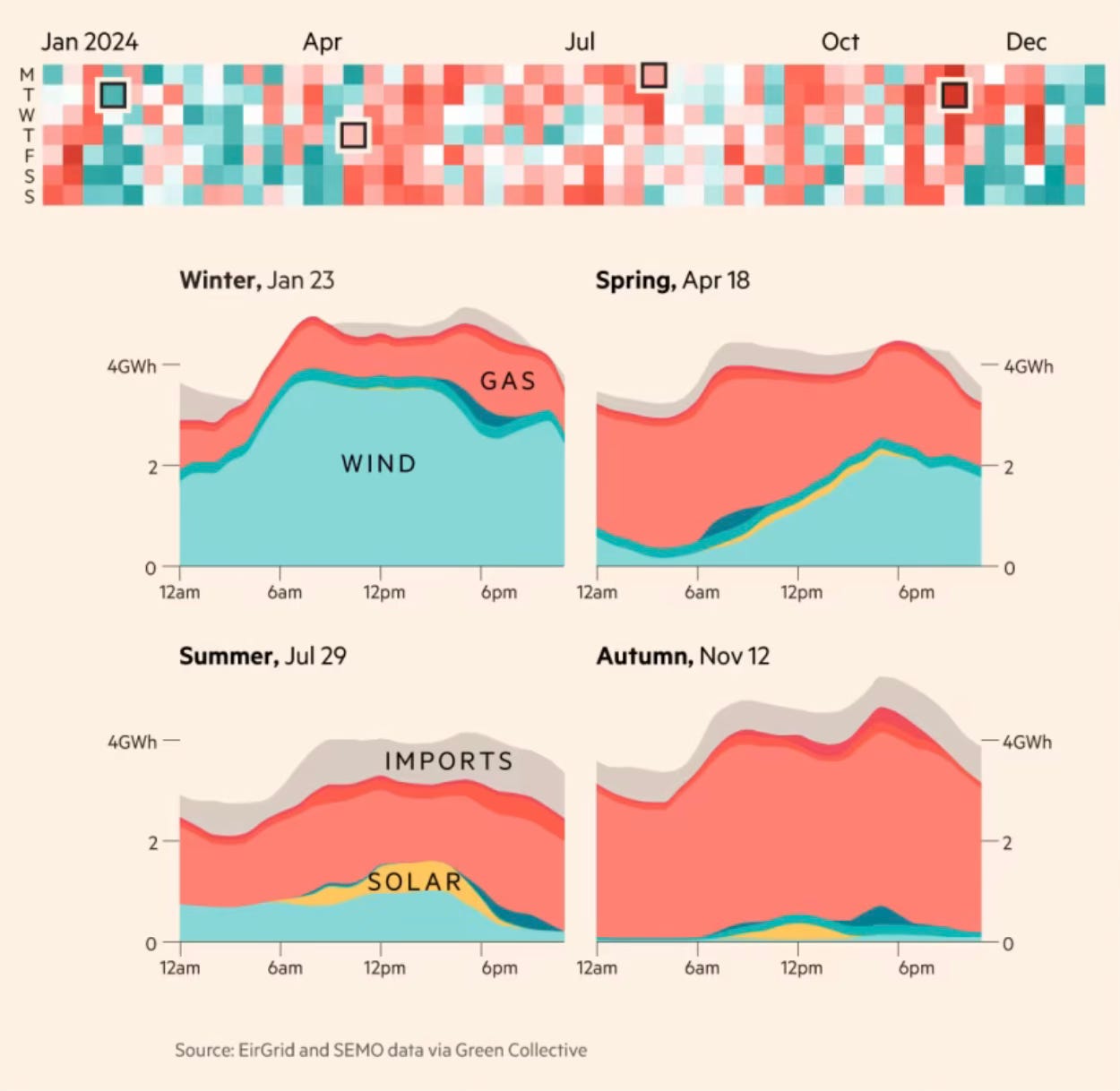

Let’s now discuss the energy demands raised by the data centre boom. As discussed earlier, an important aspect of the data centres is that they are energy guzzlers. While the energy demands of AI’s learning phase are spiky, high and volatile, data centres need constant high energy. The patterns of solar and wind, which wax and wane during the day and year, are unsuited to serve this need. In the absence of large storage capacity, given their need to be available at all times, data centres have no choice but to rely on gas turbines.

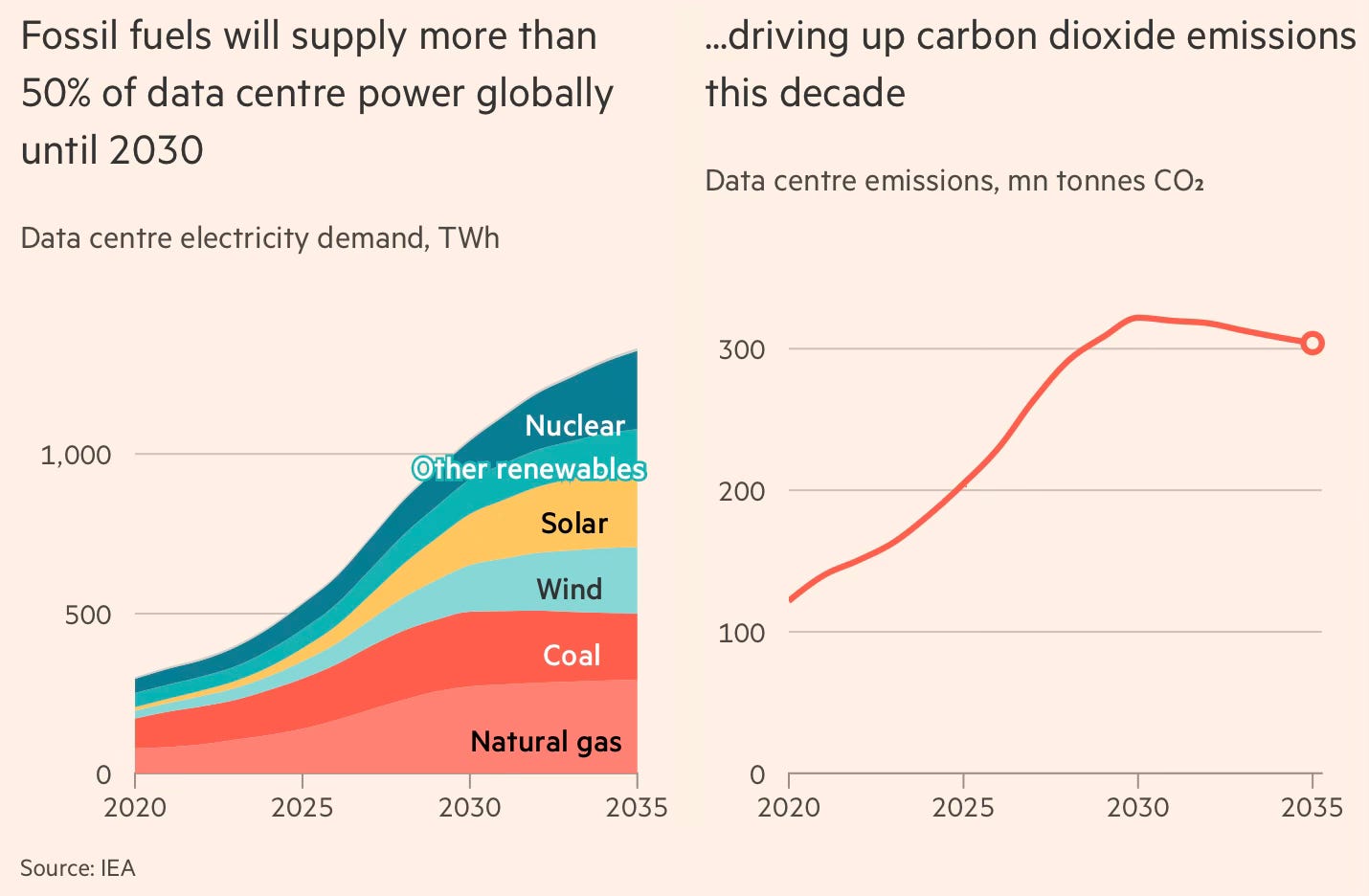

Therefore, amidst all the efforts to limit greenhouse gas emissions, the massive energy needs of data centres running AI applications and their training models have resulted in a surge of investments into fossil fuels. In fact, a fifth of all gas power capacity additions in the US is to power data centres. Globally, too, fossil fuels are expected to supply a majority of power for data centres and drive CO2 emissions.

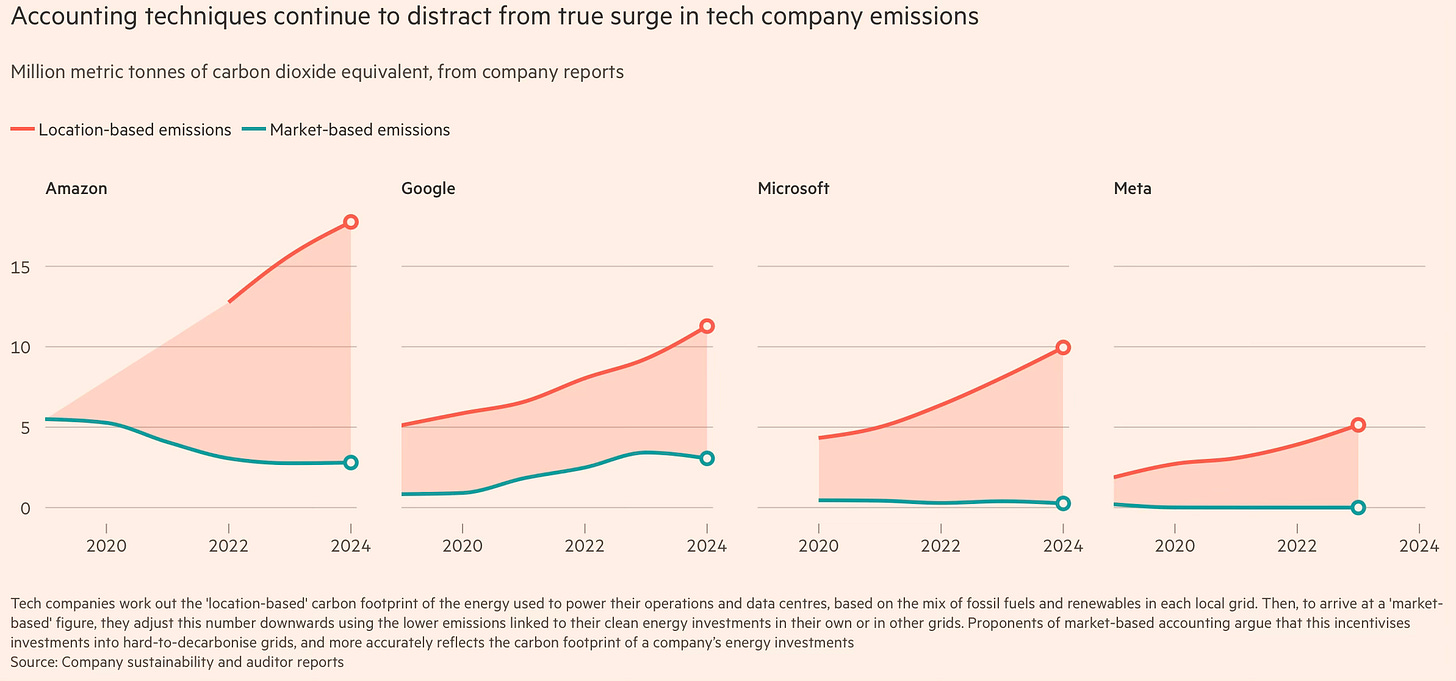

The Big Tech companies that run these data centres claim they are using clean energy, whereas they are only using green power credits that are backed by actual fossil fuel generation elsewhere. Such credits, which do not have to match the location or time when they’re used, are pure financial engineering and a well-known example of greenwashing.

As an illustration, the graphic below shows the extent of variations in how Ireland met its energy demand in 2024 (each block represents one day, red to green represents the percentage of green energy from 0% to 100%).

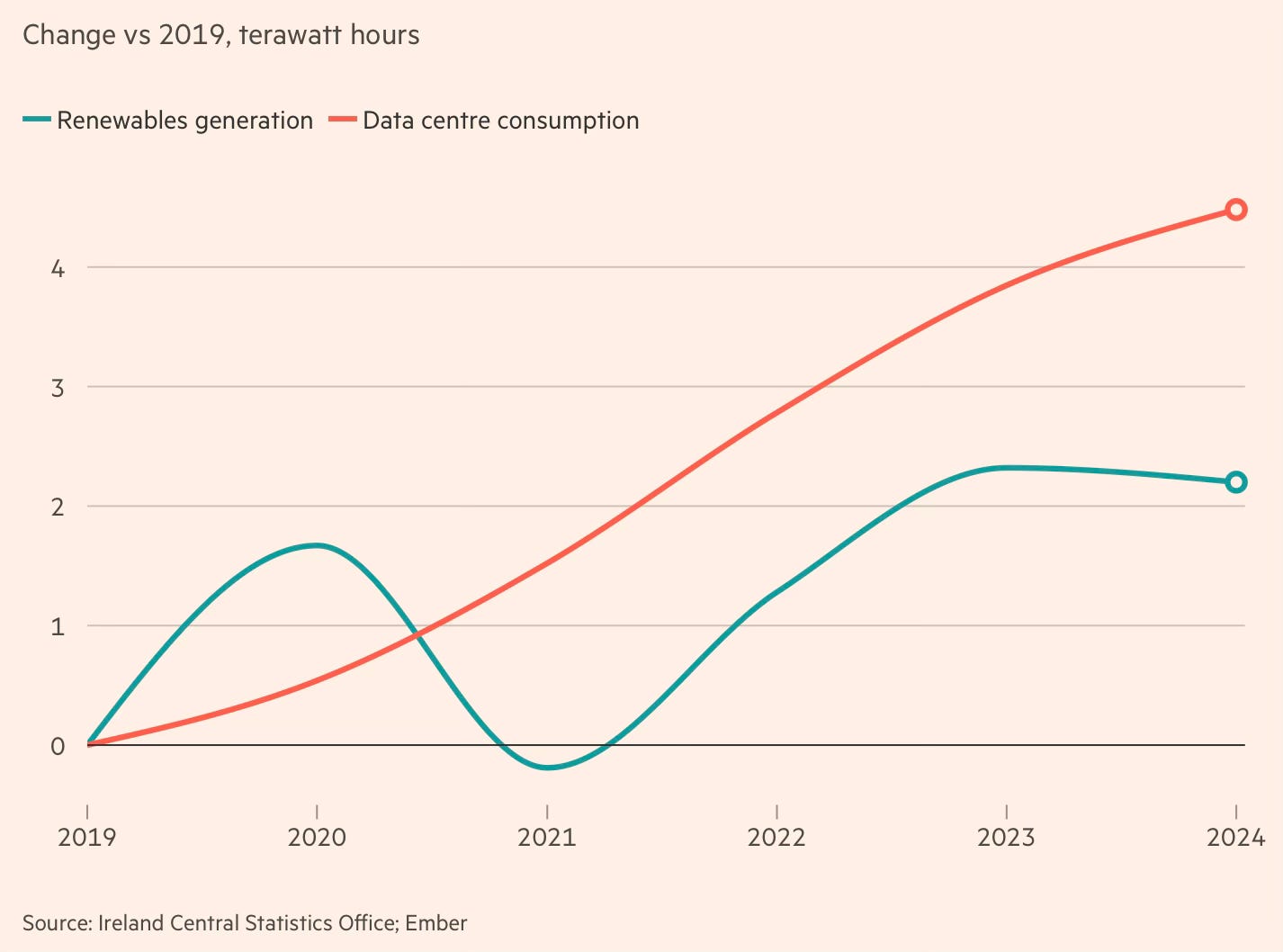

Even with solar and wind generation, highly polluting sources of energy like oil boilers and open-cycle gas turbines are used to serve peak data centre demand. In countries like Ireland, a major location for data centres, the surge in electricity used by data centres has far outpaced growth in renewable generation since 2019.

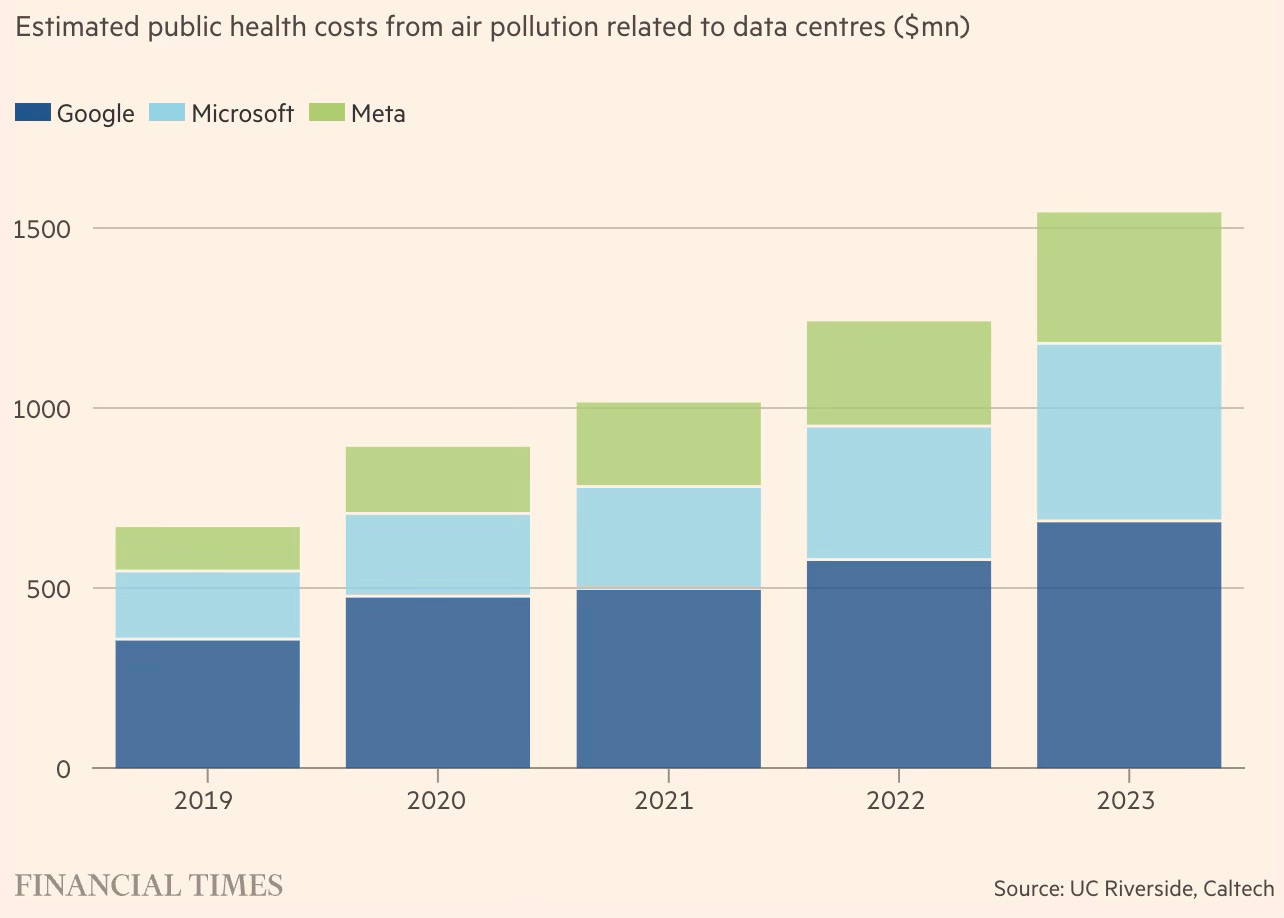

In this context, FT points to a study by researchers at UC Riverside and Caltech in the US of public health costs due to data centres built by Big Tech companies.

Big Tech’s growing use of data centres has created related public health costs valued at more than $5.4bn over the past five years... Air pollution derived from the huge amounts of energy needed to run data centres has been linked to treating cancers, asthma and other related issues, according to research from UC Riverside and Caltech. The academics estimated that the cost of treating illnesses connected to this pollution was valued at $1.5bn in 2023, up 20 per cent from a year earlier. They found that the overall cost was $5.4bn since 2019.

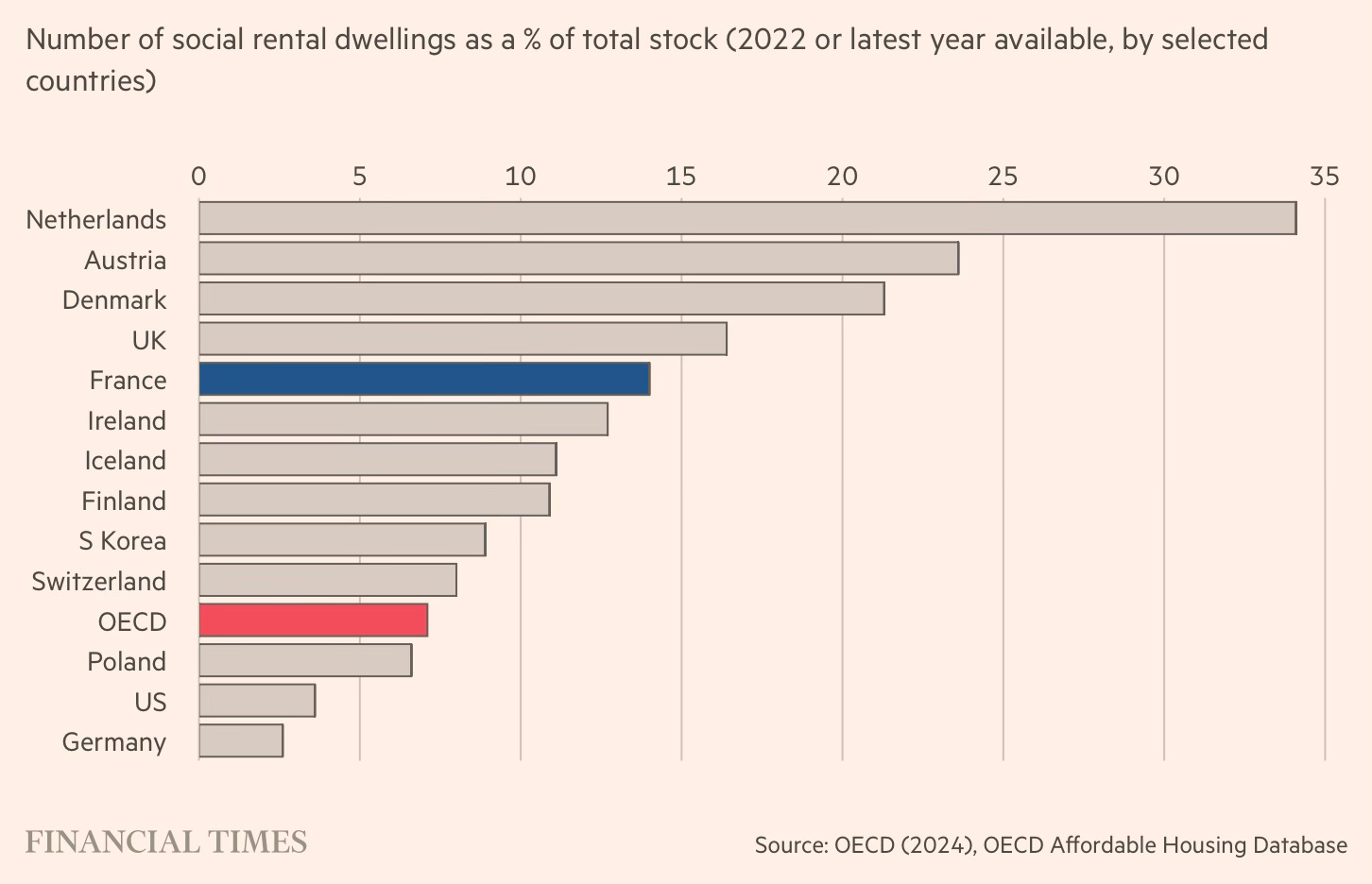

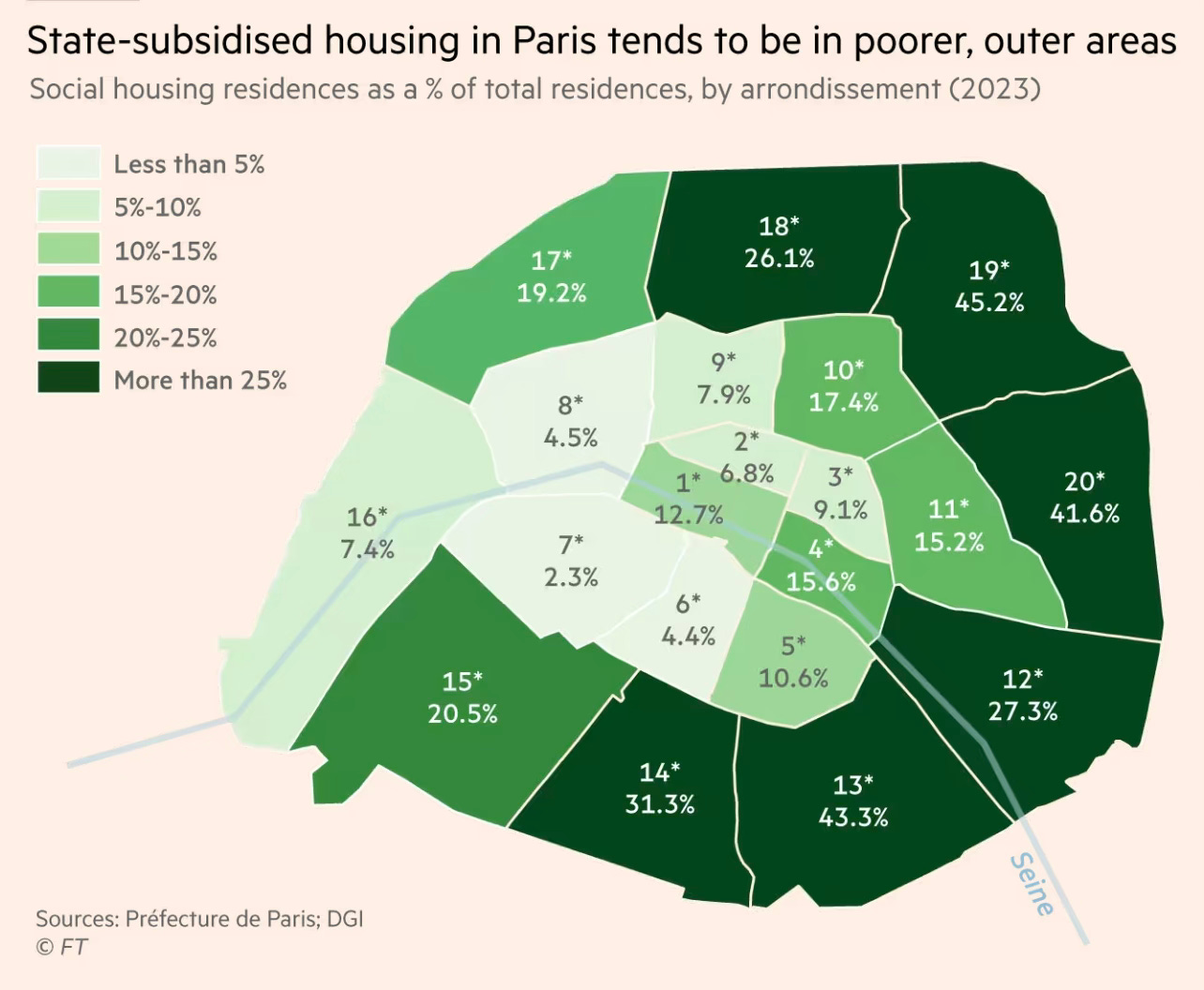

Closer home, state governments in India are rolling out incentives to attract companies to invest in solar power generation and data centres. Given the country’s macroeconomic stability and the maturity of its regulatory and political environment, foreign investors naturally find these stable and long-term return assets very attractive. But some issues must be kept in mind as we pursue data centre investments.

Apart from requiring vast amounts of power, data centres are water-intensive too (one data centre in Iowa consumed 1 billion gallons of water in 2024, enough to supply all Iowa residents for five days). See also this. Further, data centres create very few jobs (this WSJ article reports that OpenAI’s 1 million sq ft facility in Abilene, Texas, is projected to employ 100 people full time, one-fifth the number of people who will be working in a nearby cheese packing plant that is a fraction of the size). Another estimate informs that a typical data centre will employ just 40-50 full-time employees.

In the circumstances, any discussion on data centres must be linked to water and energy sources powering them. The hydel energy sources in the Himalayan frontier may not be a good choice given the security concerns of concentrating such critical infrastructure in vulnerable border areas. Wind and solar are, therefore, the obvious choices for a country like India. They require large land extents.

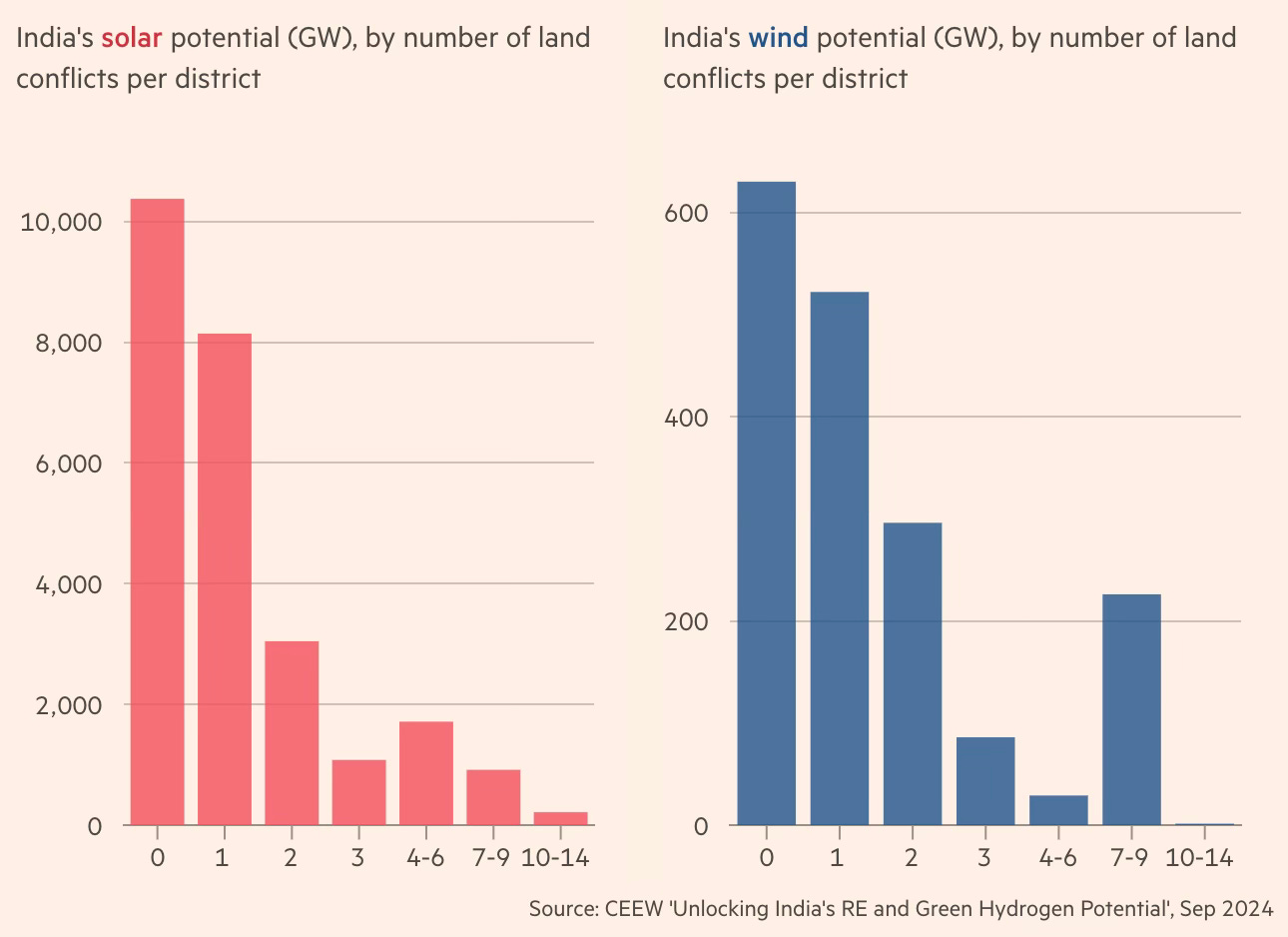

A recent FT article pointed to a CEEW study that estimates that only 35% of onshore wind and 41% of solar real estate potential in India is located in areas without historical contest over land.

About 60 per cent of India’s land is farmed, compared with the 37 per cent world average, according to the World Bank, and agriculture is the main means of livelihood for the country’s majority. The Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis estimates India’s net zero goal may require up to 75,000 square kilometres of land for solar energy alone — equivalent to the size of the Republic of Ireland or about 2 per cent of India’s total area. The Ministry of New and Renewable Energy has also calculated that a single megawatt of solar power requires on average four acres of land.

However, this side of the equation must be balanced with the critical importance of data (and therefore data centres) in the emerging digital and AI economy. Besides, there’s the strategically important issue of local storage of data. All this raises several questions and necessitates balancing both sides and moving with caution on data centres.

Since the data centre industry is in its initial stages in India, it may not be advisable to undertake deep regulation on its location choices for now. But it is important to keep an eye out and guide its emergence in an appropriately geographically diversified and environmentally sustainable manner. The recent experience of excessive concentration of solar renewables in Rajasthan, with its numerous evacuation and other policy problems, is a reminder.