This post will discuss the UK’s broadband penetration and highlight the takeaways, which are relevant not just to the telecommunications sector but more widely across utilities.

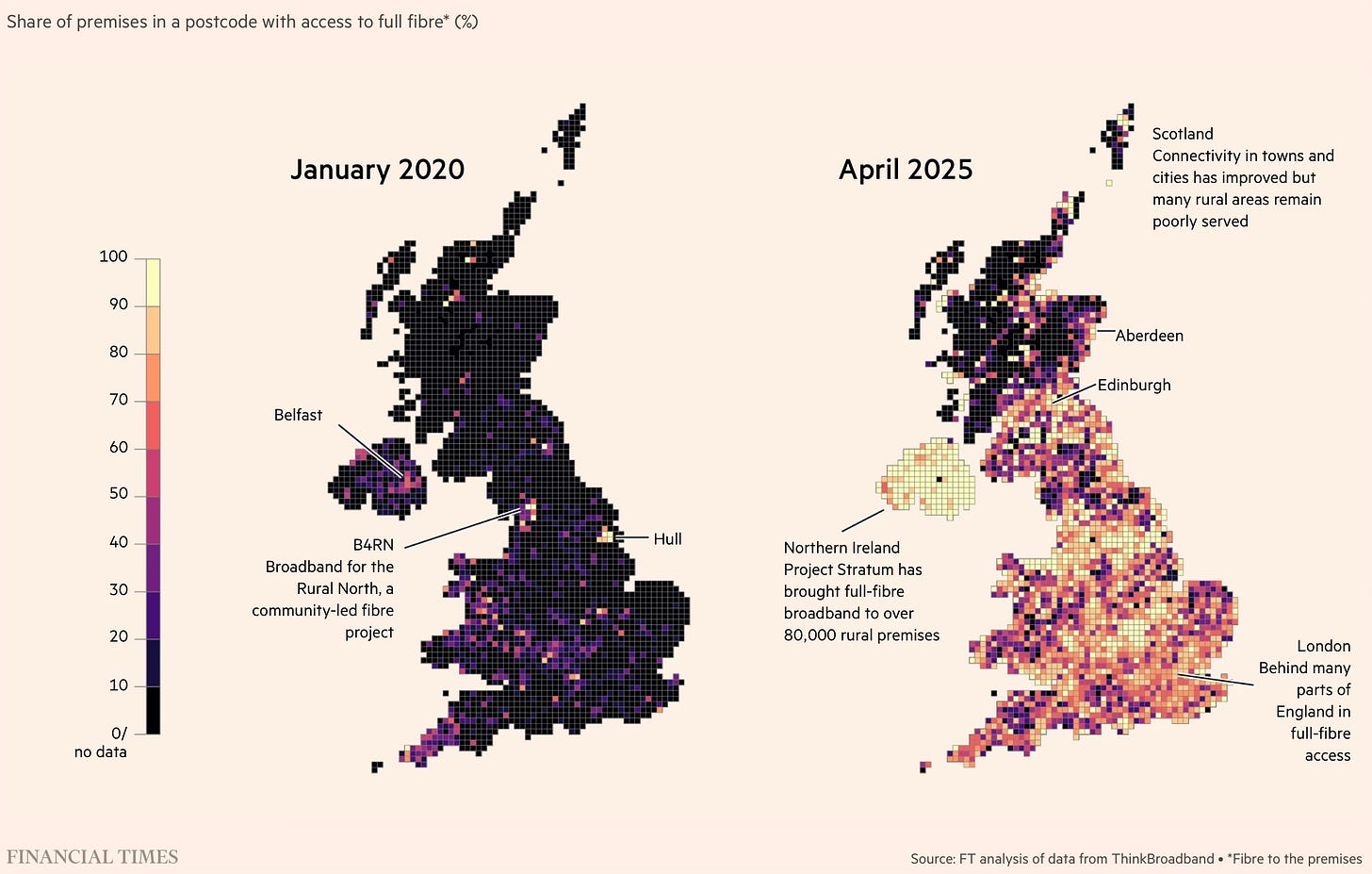

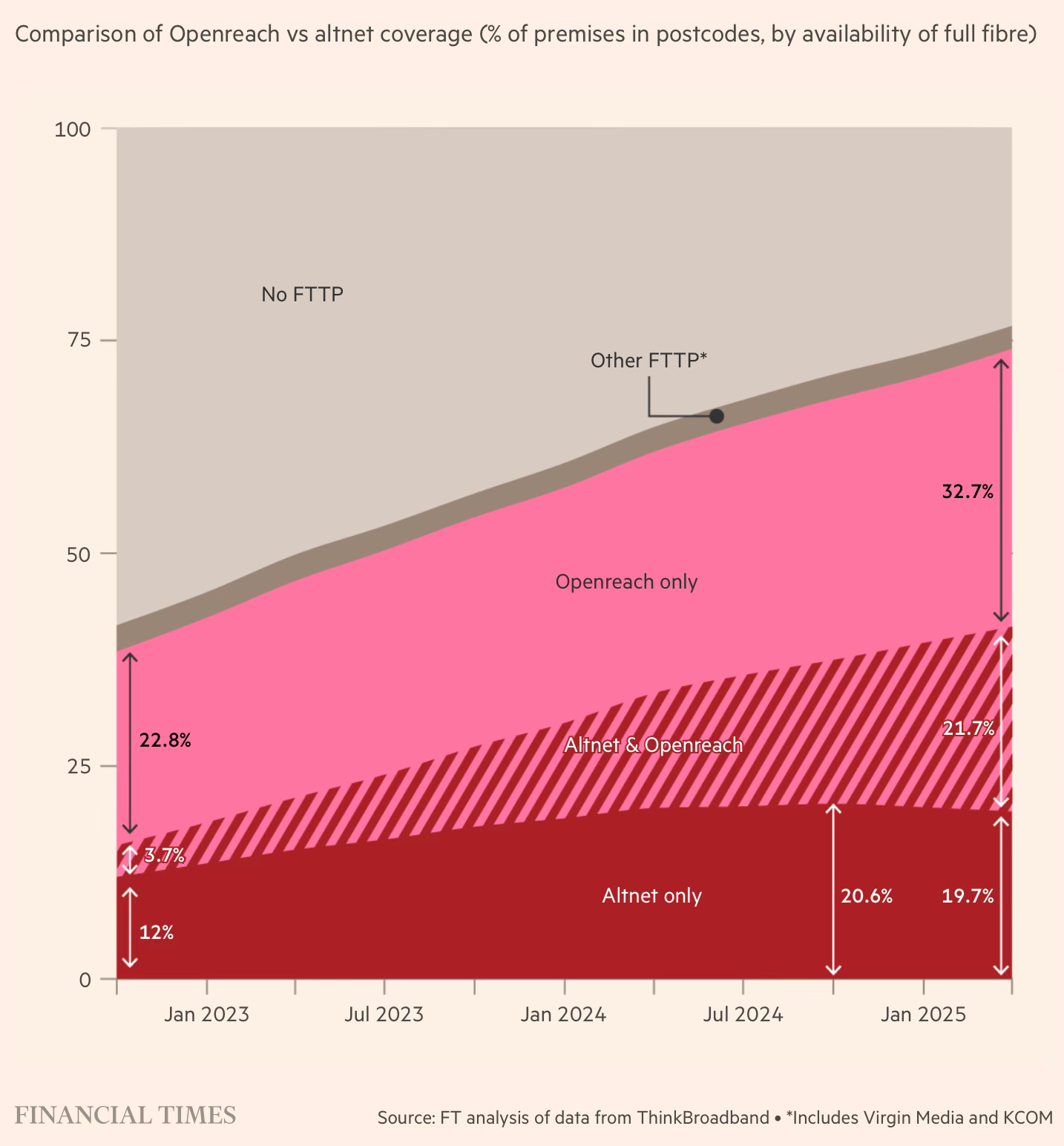

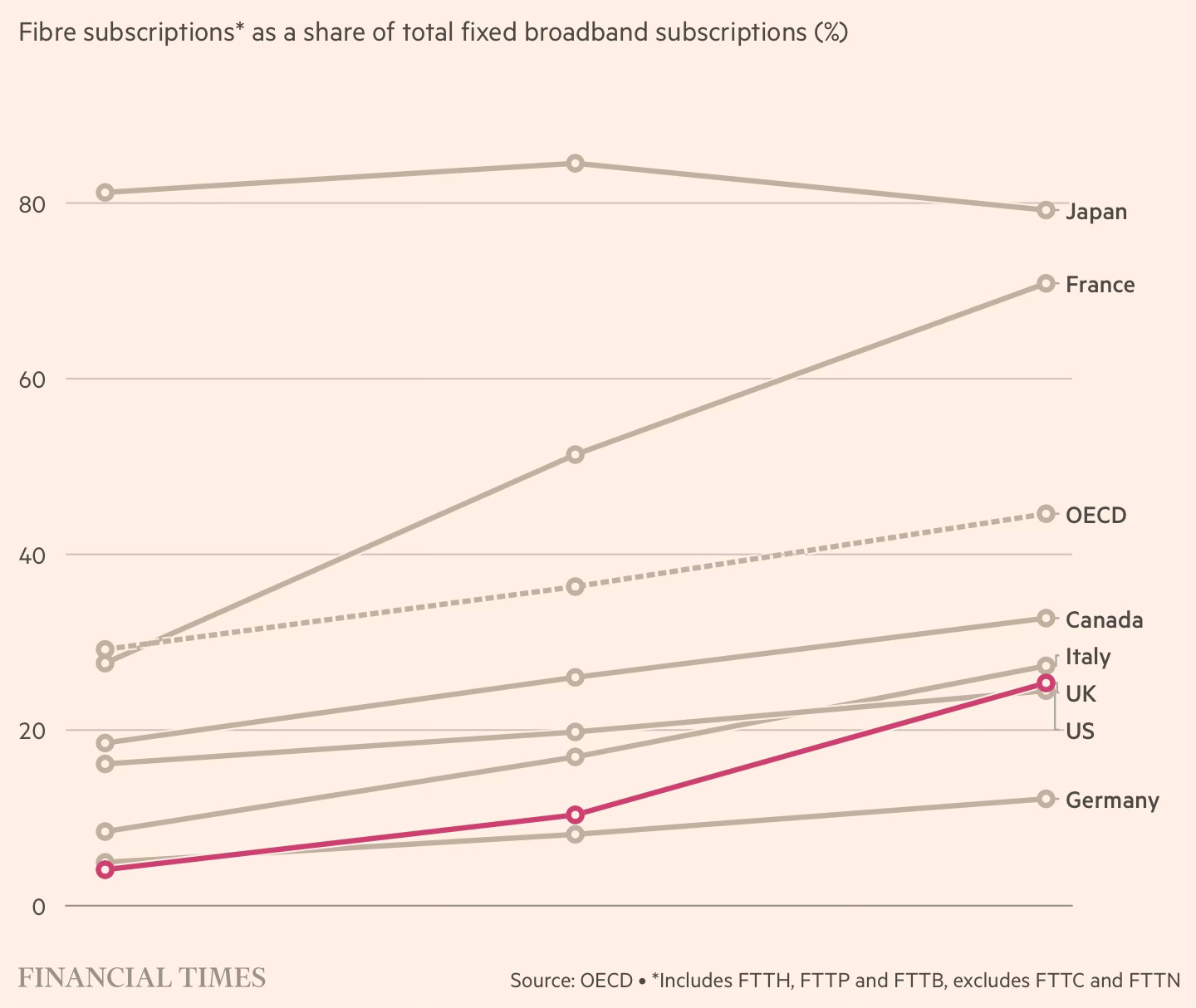

The rapid expansion of the UK’s wireline broadband penetration, from just 12% of households with access in January 2020 to 78% by mid-2025, is a spectacular success in rapid infrastructure expansion across sectors. In Northern Ireland, 96% of homes have access to full-fibre connections.

It has come on the back of some important measures taken by Ofcom to expand fibre rollout and coverage, which have aligned the incentives of incumbents and attracted large private investments. Specifically, it led to the emergence of smaller alternative networks (Altnets) that have led to the expansion of broadband penetration.

Ofcom introduced the Business Connectivity Market Review in 2016. This imposed restrictions on Openreach, including a requirement to give others access to its unlit strands of fibre… a strategic directive from the UK government in 2019, which asked Ofcom to set out a framework of “stable and long-term regulation that encourages network investment”. To meet that goal, Ofcom updated its regulatory framework for the fixed broadband market in 2021… The framework — known as Wholesale Fixed Telecoms Market Review — gave other providers access to Openreach’s ducts and poles. At the same time, Ofcom agreed not to introduce price caps on the company, in an effort to encourage investment through the promise of financial return, something known as the “fair bet”.

The result of the change was swift… “[Ofcom’s proposals] gave infrastructure investors — notably BT’s Openreach unit — the regulatory certainty to commit to large-scale fibre deployments . . . and ‘build like fury’,” adds CCS’s Mann. But Ofcom’s decision had another consequence: it opened the door to a new wave of so-called alternative networks, or altnets. These challengers — buoyed by the more favourable regulatory environment and the promise of up to £5bn in government funds to support rollout to “hard to reach” homes — began to court investors… the number of homes passed by altnet providers increased from 8.2mn in 2022 to more 16.4mn by 2025.

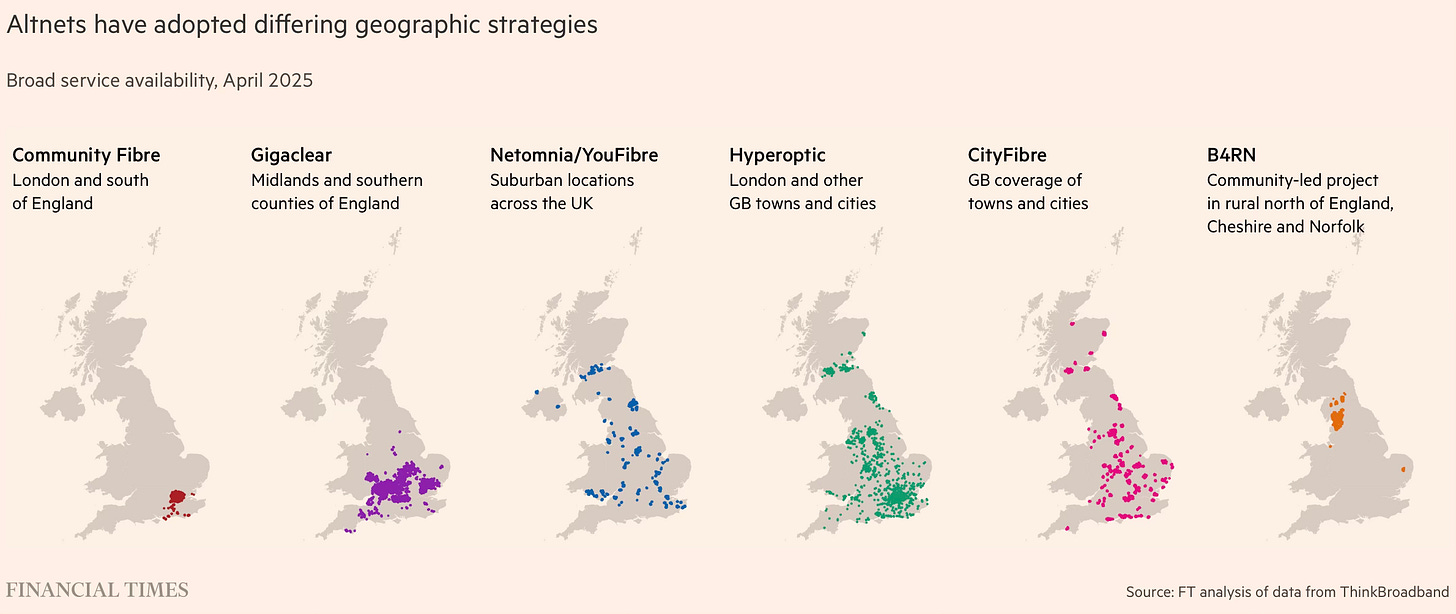

The Altnets have adopted a wide variety of geographic models in their expansion, though by-and-large preferring to avoid geographical overlap among each other, though not with Openreach.

The UK’s broadband expansion trajectory has useful learnings for other countries. In 2006, the UK created Openreach by separating BT’s network and ducts into a distinct entity to drive broadband penetration.

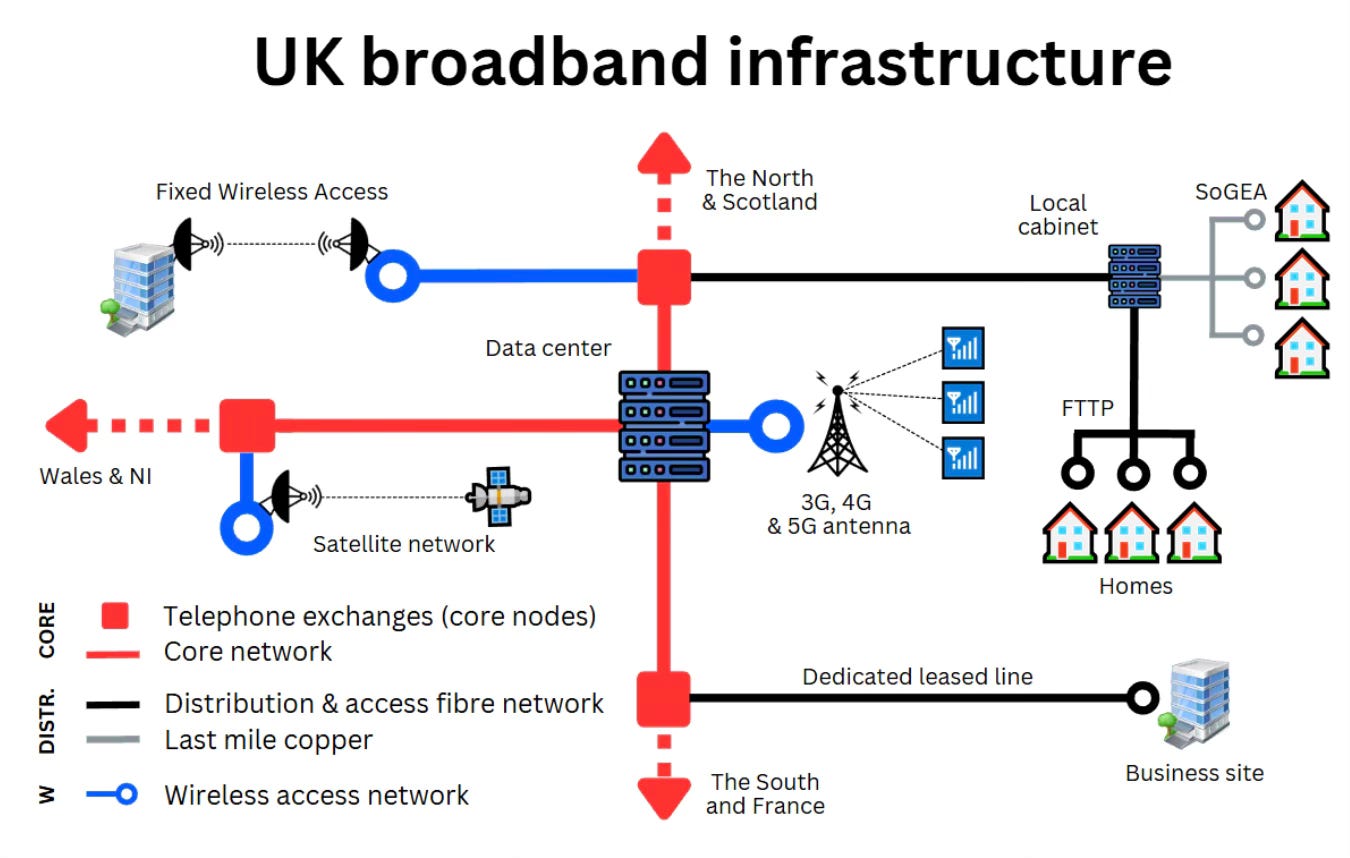

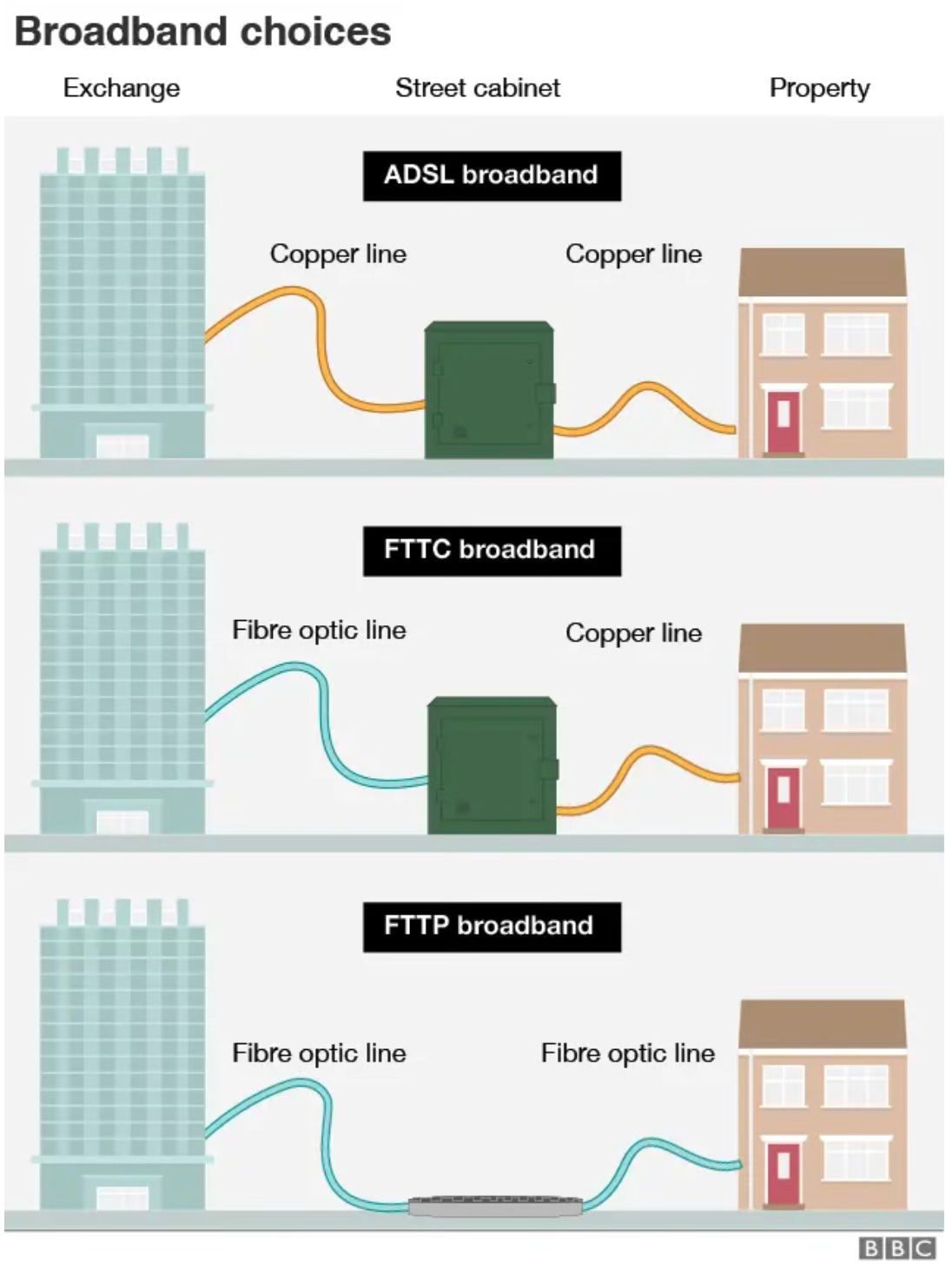

Openreach is the company that builds, maintains, and operates the UK’s largest “last mile” broadband network, used by most broadband providers. It manages the physical network of fibre cables, copper lines, and street cabinets that connect homes and businesses to major exchanges, where internet traffic passes into the provider’s core network for routing across the UK. Openreach runs as a separate, highly regulated division of BT… Openreach is regulated by Ofcom, the UK’s communications regulator. Ofcom oversees how Openreach operates to ensure it provides fair and equal access to its broadband network for all broadband service providers. Because Openreach is part of the BT Group, Ofcom introduced strict rules to keep it functionally separate from BT’s retail business. This independence helps maintain a level playing field, allowing other broadband providers such as Sky, TalkTalk, and Vodafone to use the Openreach network on the same terms as BT. Ofcom regularly reviews Openreach’s performance, pricing, and investment plans to make sure customers benefit from competitive broadband services and continued upgrades to the UK’s fibre network… A process called ‘Local Loop Unbundling’ (LLU) allows Openreach to open up parts of its telephone exchange to ISPs who have their own networks. Throughout the UK, most exchanges are now LLU. Those that aren’t have a more limited range of broadband providers.

In 2017, following criticism that Openreach was favouring BT over other broadband providers (e.g., their faults were not being attended to as fast as those of BT), Openreach was incorporated as a separate company, though a subsidiary of the BT Group. As of late 2025, its full fibre network has reached over 20 million homes and businesses, with a target of 30 million premises by the end of 2030.

This graphic captures the UK’s broadband configuration.

This is a good description of the broadband service provider landscape.

As a network operator, Openreach doesn’t sell broadband directly to businesses… Alongside Openreach, there are alternative network operators, or altnets… are independent broadband infrastructure operators that build and manage their own full fibre networks, separate from Openreach… in some cases, offer wholesale access to providers or sell directly through associated retail brands… Their purpose is to increase competition, speed up the UK’s fibre rollout, and connect areas that Openreach hasn’t yet reached. Altnets vary in scale and focus. Some, like CityFibre, build national networks and partner with broadband providers such as Vodafone Business, TalkTalk Business, and Zen. Others, including Hyperoptic, Community Fibre, Gigaclear, and Netomnia, focus on specific regions, business hubs, or rural communities.

Altnets are also regulated by Ofcom, but are not subject to the same structural separation rules that apply to Openreach because they operate entirely independently. Despite this independence, altnets often rely on Openreach infrastructure for physical access routes. Through Openreach’s Physical Infrastructure Access (PIA) system, they can use existing ducts and poles to install fibre more quickly and cost-effectively, reducing disruption and avoiding duplicate street works… Openreach and altnets often overlapping or complementing each other as the UK’s fibre rollout expands. Openreach has been replacing its copper wires with fibre by blowing optic fibre cables along its ducts with air compressors and stringing fibre from poles to houses.

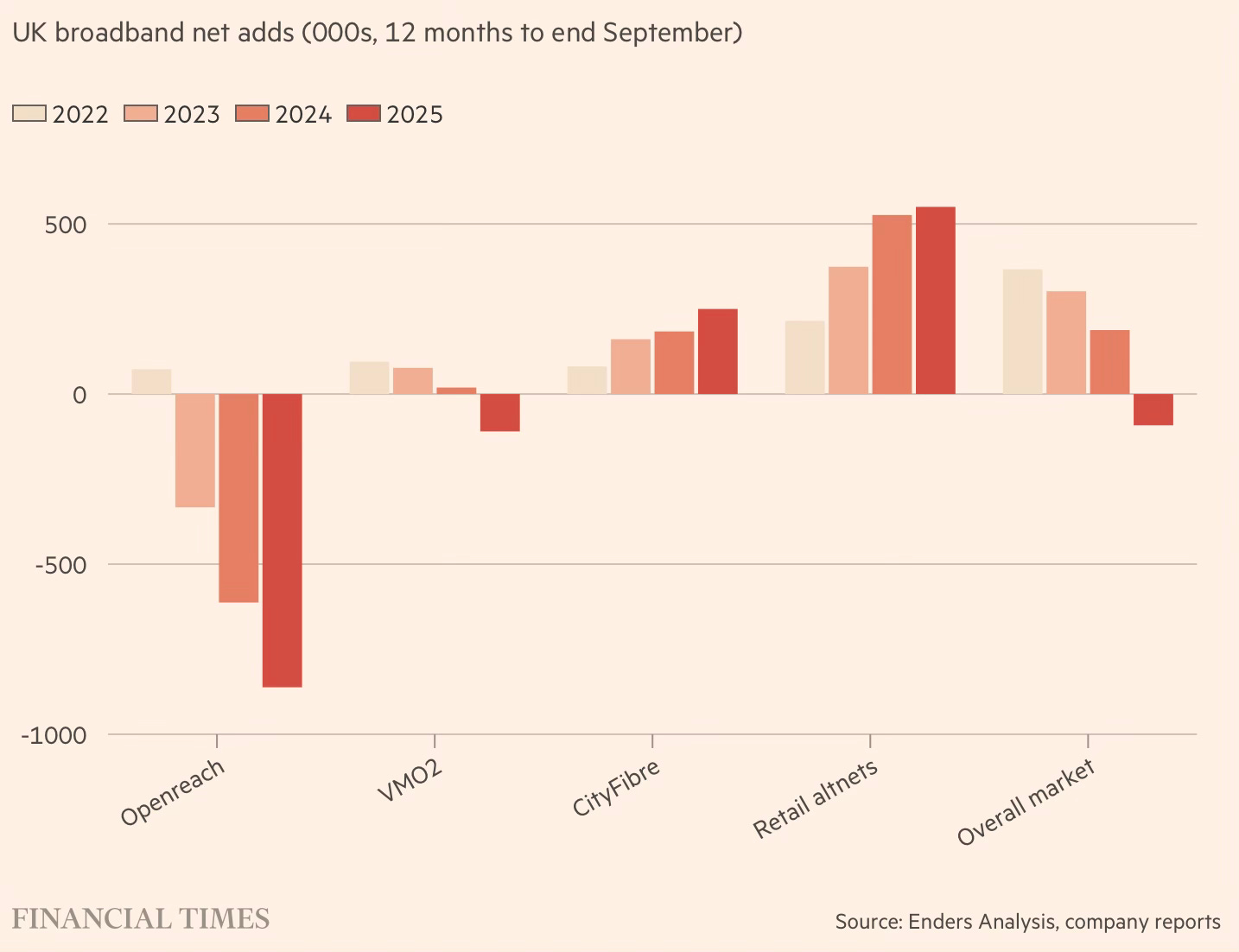

The altnets have attracted large funding, especially from private equity funds. In July 2025, CityFibre, the biggest altnet reaching 4.5 million premises, raised £2.3bn, taking the total fundraising by altnets since 2020 to £20bn. The 130-odd altnets cumulatively serve around 16.4 million premises. However, most of them are losing money, and there is an ongoing rush for consolidation through mergers.

To lower costs and thereby make subscriptions affordable, in March 2021 the British government initiated Project Gigabit, a £5 billion program designed to deliver lightning-fast, “gigabit-capable” broadband to homes and businesses, with a focus on rural and “hard-to-reach” areas. It is expected to reach 99% of UK premises by 2032.

The Gigabit Broadband Voucher Scheme (GBVS) is a government programme run by Building Digital UK (BDUK) to help bring full fibre broadband to homes, small businesses, and community buildings in areas with poor connectivity. It offers funding worth up to £4,500 for each eligible property that gets connected, and in some areas, local councils provide additional top-up funding, which can increase this to more than £7,500. The funding doesn’t go to the homes or businesses themselves. Instead, it goes to an approved broadband supplier to help cover the cost of building the new fibre network. To access the scheme, several nearby homes and businesses need to club together and approach a registered supplier. The supplier then pools their vouchers, applies to BDUK for funding on their behalf, and builds the connection. Once the new network is live and confirmed to deliver gigabit speeds, BDUK pays the voucher money directly to the supplier. This reduces or removes the upfront installation costs for the homes or businesses taking part.

Ofwat has initiated several measures in recent years to nudge broadband penetration across UK.

As part of the measures, Ofcom will effectively freeze the wholesale fees Openreach charges for providing "superfast" data speeds of up to 40 megabits per second, which rely on copper links via fibre to the cabinet (FTTC) or older technologies… The price Openreach charges for faster and more reliable FTTP connections will remain unregulated. There is, however, one new restriction. Openreach will not be allowed to offer geographic discounts on its full-fibre wholesale services. A similar limitation already existed on its provision of “superfast” links. And Ofcom has said it will review all long-term discount arrangements offered by Openreach to its clients, and will intervene if necessary to prevent the firm from stifling investment by rivals… The altnets’ ability to profit from building rival networks would have come under pressure if they had been required to match new full-fibre price caps imposed on Openreach…

If it set regulation too tight by capping wholesale prices at a low level, the risk was that BT and its fibre network rivals would be reluctant to invest the billions needed to roll out ultrafast broadband. If it loosened the reins it would be accused of going soft on BT, sparking anger from the likes of Sky, which use the Openreach network and would have to pass on the higher prices to their retail customers. By opting to impose no price controls on BT’s fibre product for a decade, Ofcom has chosen the second option, insisting that it is the only way to spark the frenzy of competitive network building needed to move the UK up into the broadband fast lane.

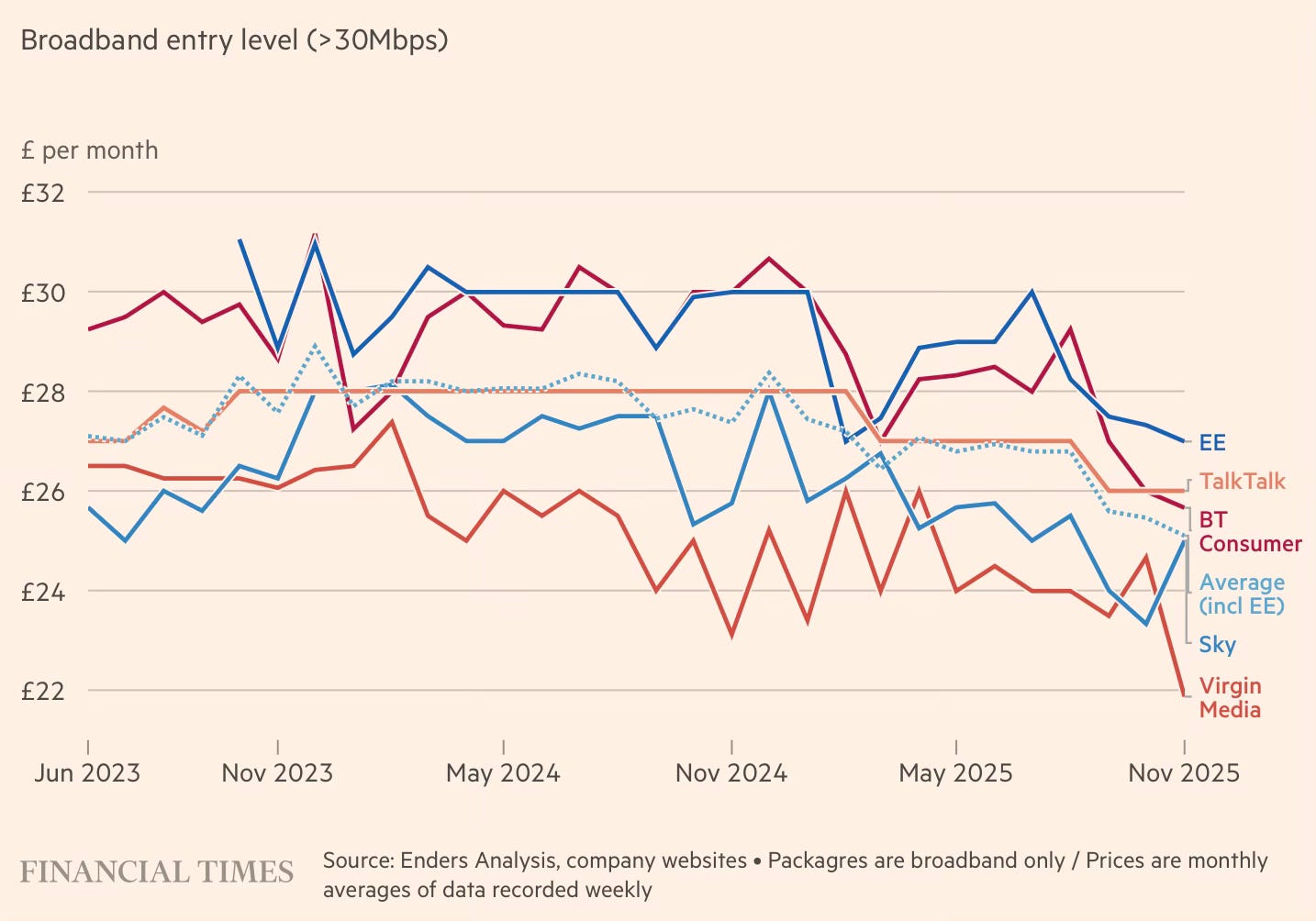

This has unleashed fierce competition involving the altnets.

The altnets suffered £1.5bn net losses in 2024, while Openreach lost a net 828,000 customers in that year. The rivalry was unleashed by the telecoms regulator Ofcom in 2021. It capped the wholesale price that Openreach could charge retail providers such as TalkTalk for services carried over copper for the final stretch from street cabinets, but let it charge more for full fibre connections. Altnets were encouraged to take on Openreach by using its ducts and poles. This has been good for consumers: prices have been squeezed by cut-price offers, especially in areas with several network operators. But it has taken a toll on the altnets, with G.Network being sold to a distressed debt firm this month. Openreach now wants greater freedom to cut its wholesale prices in the most competitive areas but keep them higher in others.

Openreach itself has been losing customers as the altnets have expanded theirs.

It is also important that, before the entry of the altnets and competition from them, the near monopoly of Openreach (80% of the market in 2016) was stalling fibre rollout in the UK.

Rather than updating its copper network to the most advanced fibre-to-the-premises (FTTP) infrastructure, Openreach had opted for a fibre-to-the-cabinet (FTTC) network model — a form of partial upgrade. Under this approach, copper lines across the country were replaced by fibre to small cabinets in neighbourhoods, where it then connected back to original copper lines that stretched to the home… The limitations of FTTC were evident. Not only was it a slower service, it was ultimately more expensive to maintain due to the copper element… Openreach continued to invest “in incremental upgrades to its existing copper network”, says Ben Harries, director of competition policy at Ofcom. “The rationale for that was that incumbents often prefer to sweat existing assets over investing in new ones”…

By the late 2010s, the UK’s lack of FTTP coverage was concerning the government and its regulator, which watched countries including Spain and Portugal rapidly adopt newer, faster, more reliable technology. The issue led to a series of fiery clashes between then BT chief Gavin Patterson and his counterpart at Ofcom, Sharon White, over Openreach’s slow rollout of FTTP. By 2016, things had escalated and the regulator ordered the telecoms company to legally separate Openreach from BT.

It is important to also note that while nearly 80% UK households have access to FTTH, just 38% of them have chosen to take connections as on July 2025. In general fibre subscriptions remain in the 15-40% households range across most developed countries.

The UK’s experience with broadband penetration has some general lessons for the infrastructure sector. Foremost, it highlights the importance of policy steering in guiding the course of sectoral growth. The UK government and Ofcom’s multiple interventions - the transfer of BT’s wire assets to Openreach, its incorporation as an arms-length subsidiary of BT, its non-discriminatory access to its unlit fibres to other service providers, removal of tariff ceilings on OFC network for a decade while retaining them on legacy wires, etc. - have been central to the UK’s success. All of these have been complemented by the UK government’s Project Gigabit scheme to facilitate broadband access in remote areas.

An important principle underlying these measures was highlighted in the UK government’s strategic directive of 2019 that demanded Ofcom create the framework for “stable and long-term regulation that encourages network investment”. These measures gave businesses the confidence to invest for the long term.

Each of these measures realigned distorted incentives, spurred entrepreneurship, and crowded in private capital. They have encouraged the entry of over a hundred altnets, who have shaken Openreach out of complacency (in the late 2010s, Ofcom clashed with BT over the slow pace of fibre rollout by Openreach), and the resultant competition has turbocharged broadband penetration in the country.

The altnets have been critical for enabling last-mile delivery, a critical bottleneck in ensuring access to households. Interestingly, this last-mile access is being delivered neither through micro-entrepreneurs nor the legacy national internet service providers, but mainly through localised mid-sized enterprises.

For sure, many of the altnets are unlikely to survive the consolidation wave that is sweeping the market, and many investors will lose their shirts. This is the dynamics of the market playing out, as it has historically from railways and power generation, to telecommunications now.

No comments:

Post a Comment