FT has an excellent interactive graphical feature on the growth of mega batteries that store electricity for grids. The growth in grid-scale batteries since 2021 has been spectacular.

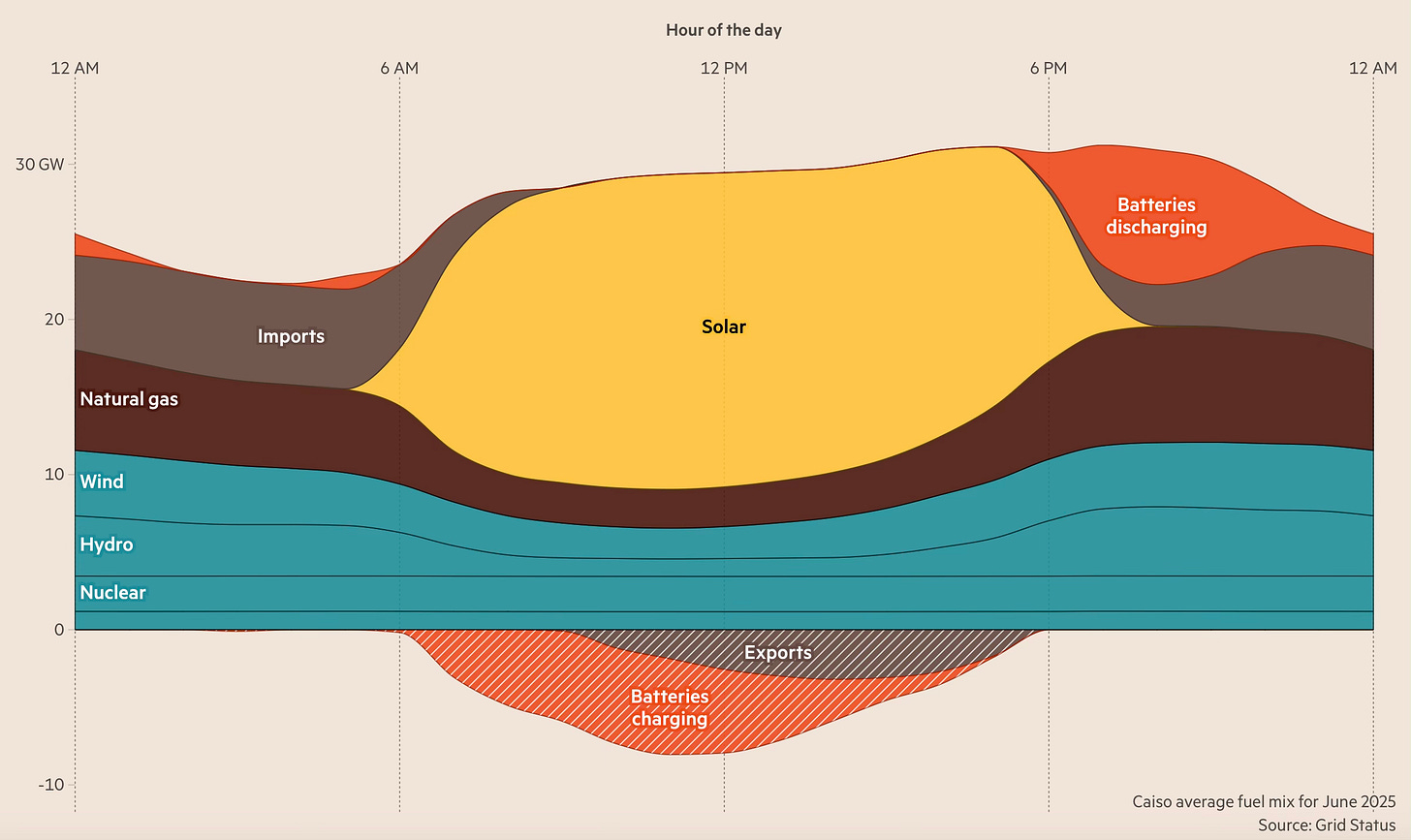

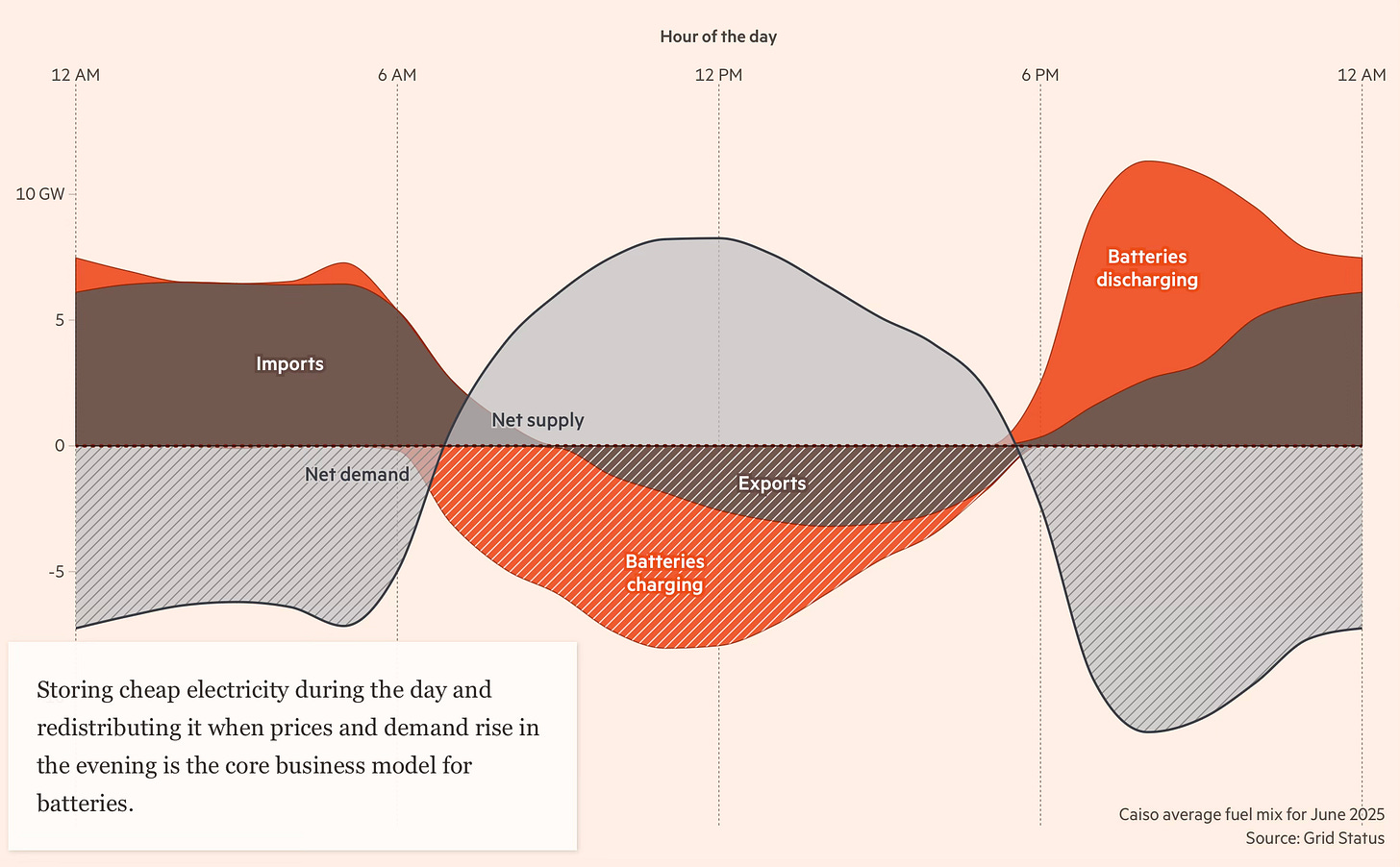

This graphic shows the load mix profile of California’s electricity grid on a typical summer day.

Enabled by state policies, California’s battery storage capacity has more than tripled to 13GW of power, with plans to add another 8.6GW by 2027. Now, as cheap, plentiful solar power floods the grid in the middle of the day, hundreds of battery installations bank the energy and discharge it in the evening when people return home from work and demand — as well as prices — spike. This has shored up the grid, extended the state’s use of renewable energy and reduced its reliance on fossil fuels.

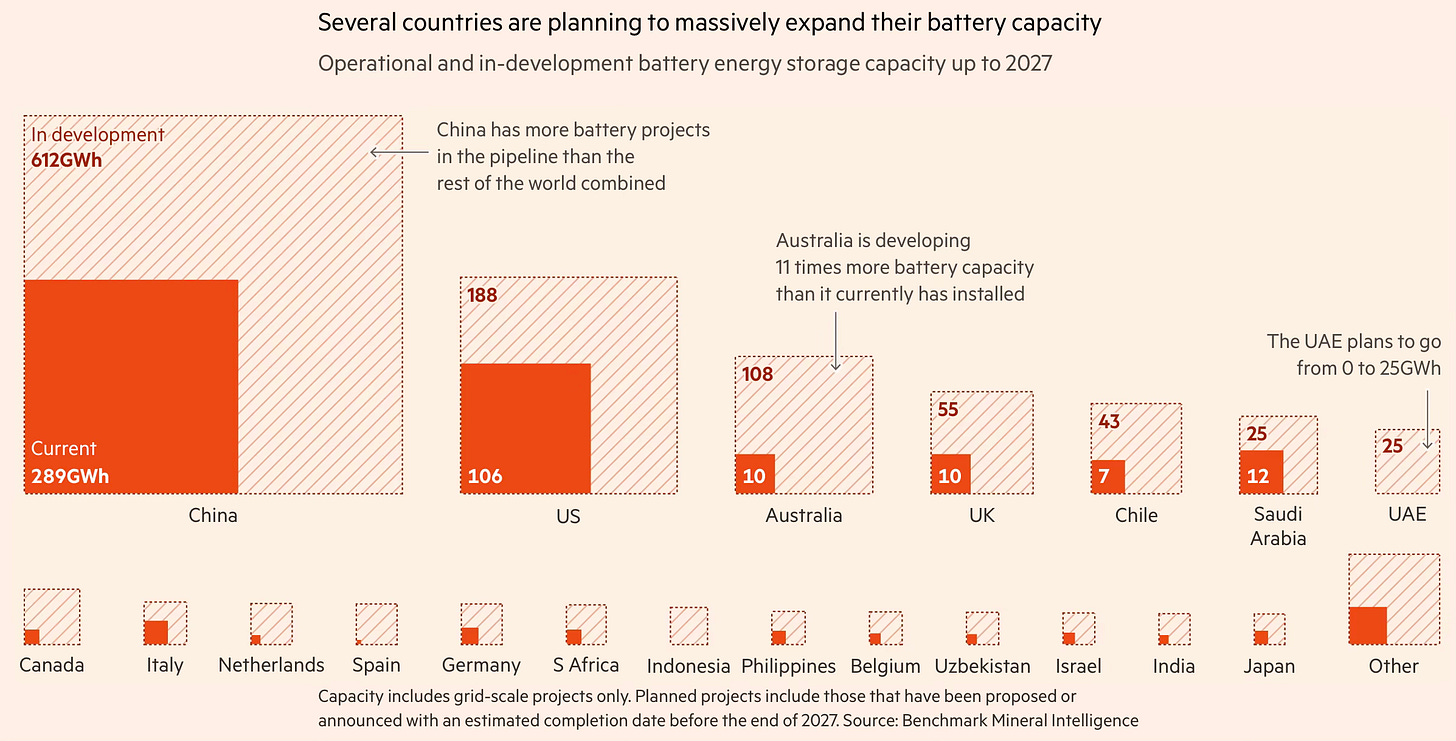

The global battery storage market is dominated by China and the US, with over 70% of the projects by capacity. Most batteries in use today can discharge power for 2-4 hours.

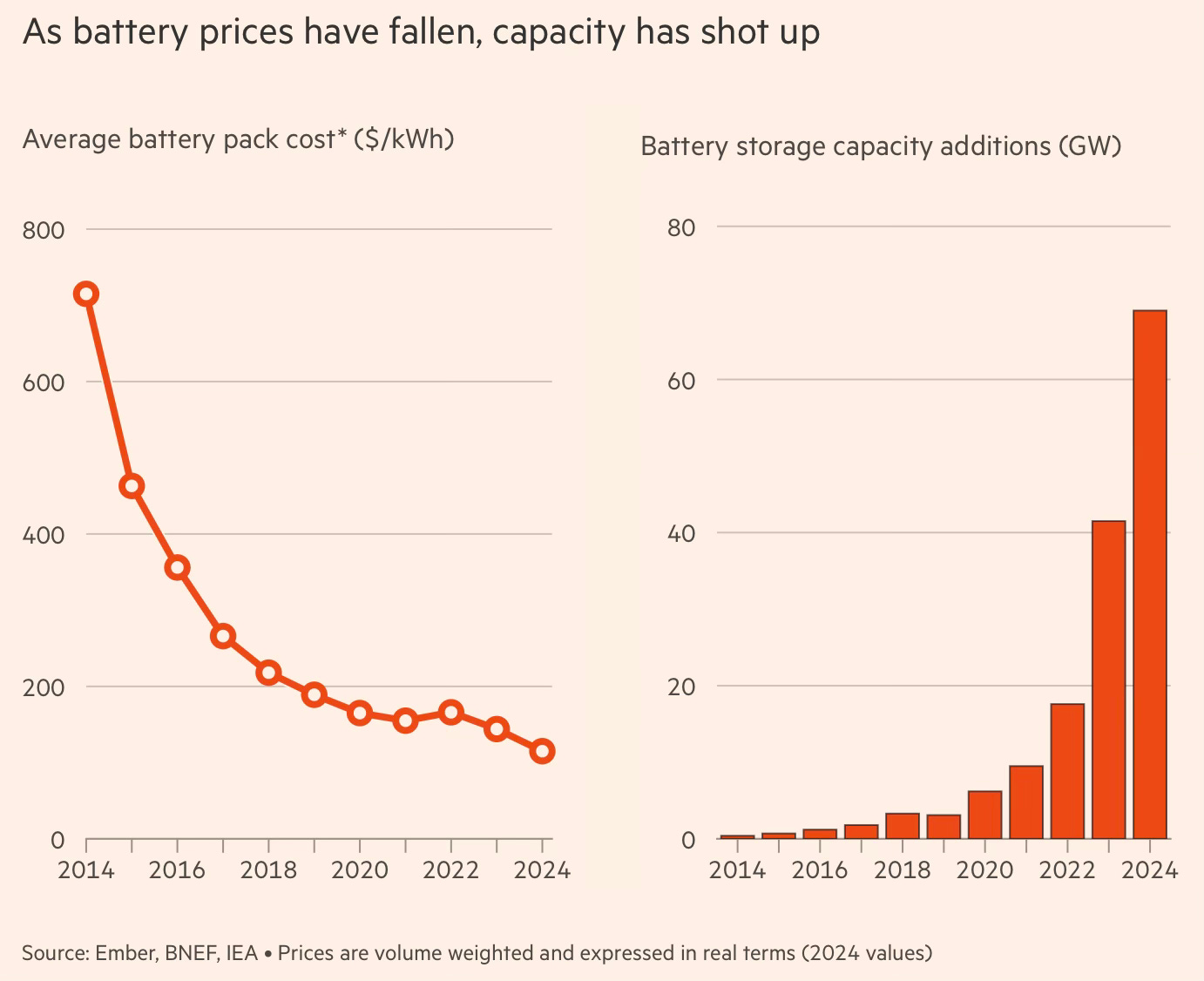

Global battery prices have fallen by more than half over the last two years.

Lithium-ion battery costs have also fallen — by 90 per cent since 2010 — a drop that Artem Abramov, deputy head of research at energy consultancy Rystad, says is likely to continue. Packed full of hundreds of powerful batteries, a standard 20-foot storage unit once provided 3-4 megawatt hours (MWh). Now they typically deliver 5-6MWh, with several suppliers developing 10MWh containers — enough to power around 30,000 UK homes for an hour.

There has been explosive growth in the number of 1 GW battery farms.

In 2022, there wasonly a single gigawatt-scale facility — defined as having a capacity of at least1GWh, able to supply roughly 3mn UK households for an hour — inoperation worldwide. Today there are 42 such sites. Five times as many giga-projects are set to come online in the next couple of years, including in the UK, the Netherlands, Chile and the Philippines.

As in other clean technology segments, China is the undisputed global leader.

China, which produces over three-quarters of batteries sold globally, has played a crucial role in the energy storage boom. Chinese companies, supported by state backing, have brought down costs through mass production. Domestic demand in China is also skyrocketing, with Bernstein predicting a 90 per cent year-on-year rise to 335GWh by the end of 2025… Driven by both strong power consumption growth — from data centres, electric vehicles and air conditioning — and the country’s long-term replacement of coal with renewable energy, battery storage demand in China is expected to reach 652GWh by 2030, at a compound annual growth rate of 14 per cent, according to Bernstein data… China’s battery makers, benefiting from sustained policy support and amid fierce market competition, are investing in options which can store more energy, such as solid-state batteries.

Mega batteries stabilise the grid by balancing supply and demand, restarting the system in emergencies, providing back-up capacity when required, etc.

“What grid operators and utilities value from batteries is flexibility,” says Mark Dyson, a managing director at the Colorado-based nonprofit RMI. “They can be a ‘swiss army knife’ and do whatever is needed on the grid, when and where that is required.”

But the volatile nature of the electricity demand profile makes for a great trading opportunity for battery owners.

Battery owners can buy low when supply exceeds demand, and sell high when demand kicks in.

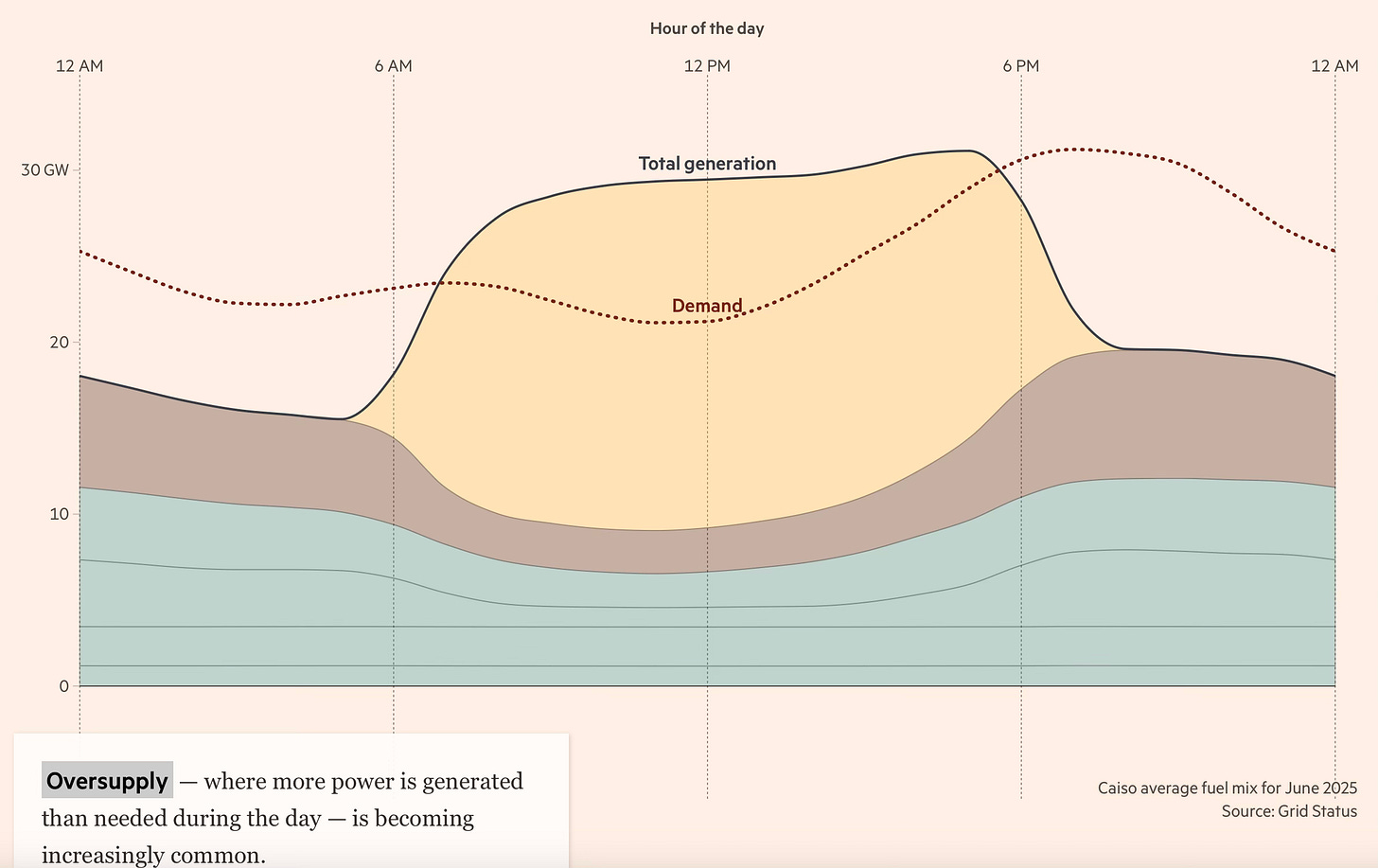

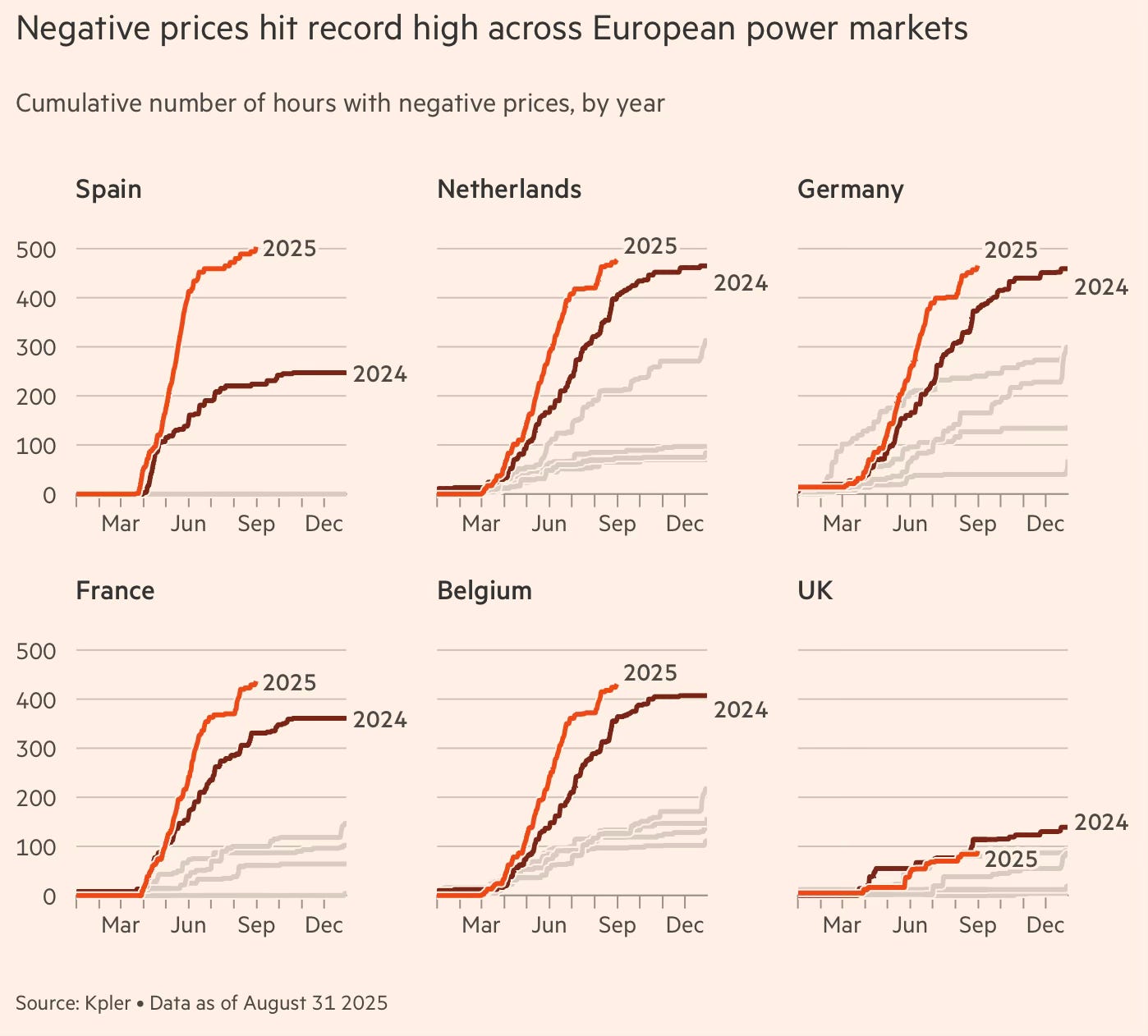

It is common for wholesale electricity spot market prices to fall below zero on especially sunny or windy days, forcing producers to either pay wholesale customers or storage operators to offtake the excess power, or switch off.

Spain, where nearly a third of summer supply came from solar power, logged more than 500 hours of prices below zero this year, having never experienced them before 2024.

Battery operators can capitalise on this price volatility.

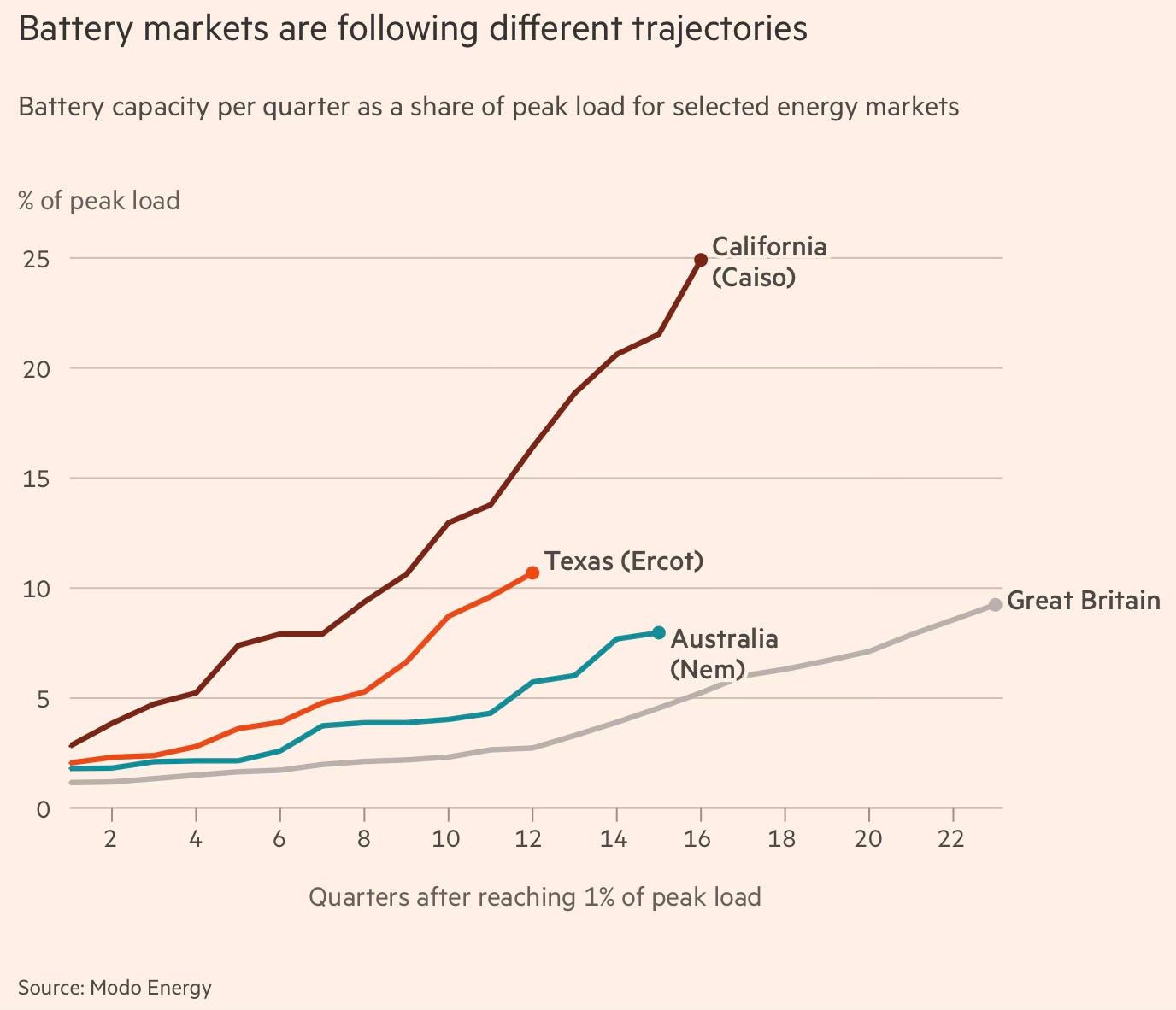

Outside of China, California has been at the forefront of battery storage.

In California, batteries consistently supplied more than a quarter of electricity during this year’s spring and summer peaks, data from energy analytics platform Grid Status shows. In the first eight months of 2025, gas generation was down 37 per cent from 2023, according to climate academic Mark Jacobson of Stanford University. In Australia, several battery farms are being installed at the sites of retired coal plants. The country’s grid-scale battery storage power capacity has more than tripled since the start of 2024 and in early May, batteries contributed more than 5 per cent of power in the evening peak for the first time.

Batteries are especially likely to be useful for countries with abundant solar power.

Research by the Energy Transitions Commission (ETC) shows that in “sunbelt” locations — countries from India to Mexico with ideal conditions for solar power — batteries could meet almost all power balancing needs. In these regions, solar follows a predictable daily pattern and is relatively consistent between seasons, enabling batteries to play a role on a daily basis. This presents a “huge economic opportunity”, says Elena Pravettoni, head of analysis at the ETC, a global coalition of companies working towards a net zero economy by 2050. “The combination of solar and batteries means clean power costs in sunbelt regions could be 50 per cent lower than today’s fossil-based systems.” In countries more reliant on wind power — such as the UK, Germany and Canada — batteries alone will not suffice, according to the ETC. Wind is less consistent, and current battery technology cannot fill the gap over multiple days.

The feature also talks about an important requirement for investments in batteries - policy certainty.

“These projects aim to be online for around 15 to 20 years, but if you only know the policy for the next one to five years then that causes a big issue,” he says. “This creates a lot of uncertainty for investors and developers.” In some countries, batteries are subject to double-charging, having to pay fees to draw power from the grid as well as when injecting energy back into it. This illustrates the complicated regulatory and policy frameworks developers must navigate. The US has seven wholesale power markets, each with their own rules, policies and price signals, while the EU’s patchwork of regulations poses its own challenges.

It points to emerging business models.

To manage risk and lock in a stable source of income, some developers are turning to tolling agreements, particularly popular in Germany’s burgeoning market. Under these contracts, the developer effectively hands over control of the battery to a third party — typically a large utility or energy company with a broad portfolio of assets — in exchange for a fixed price.

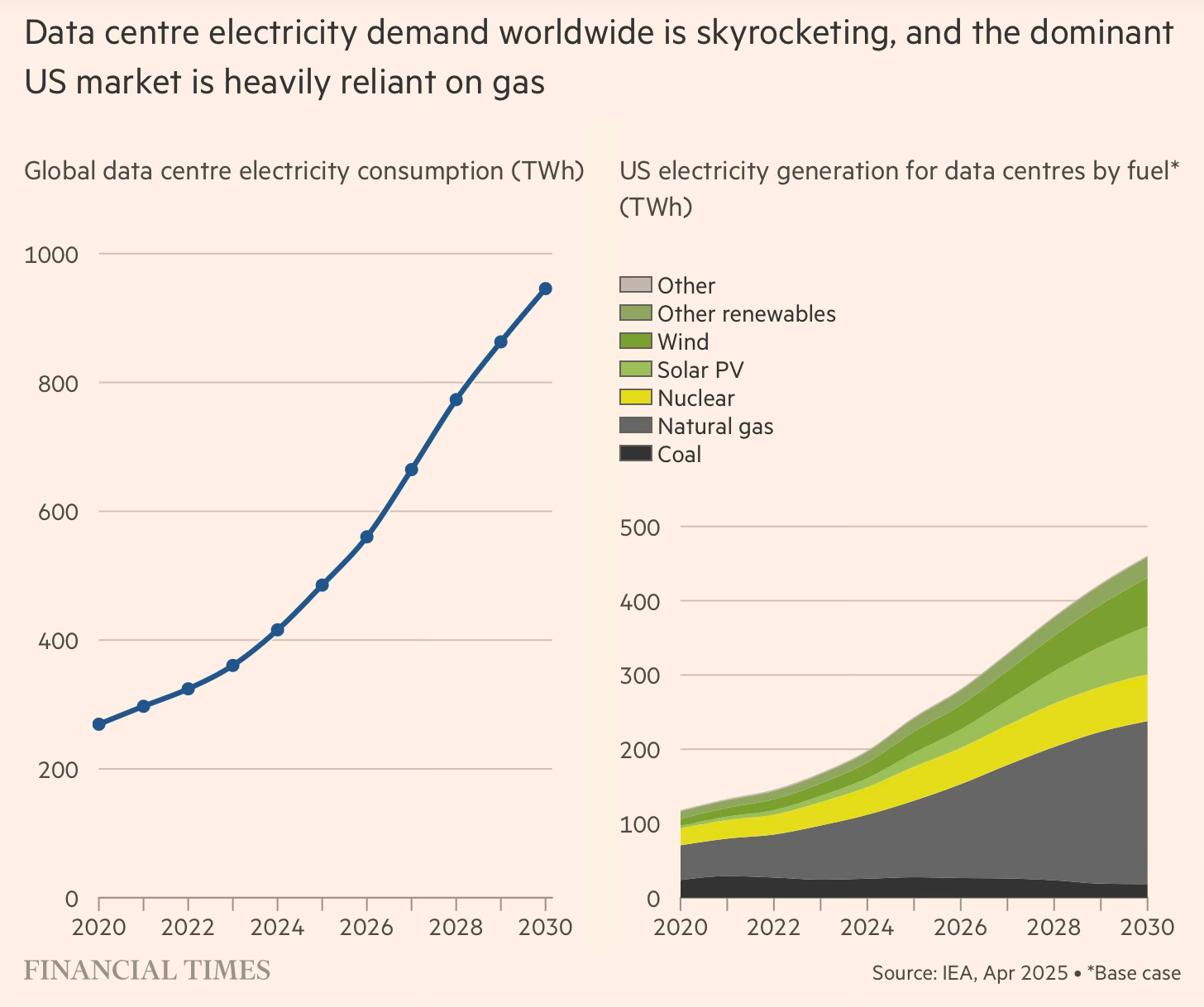

Battery storage assumes added importance given the explosive demand for energy-intensive data centres. As in the US, much of this new demand is being met with natural gas. The International Energy Agency estimates that globally, data centres’ electricity usage would double to 945 terrawatt hours by 2030.

In this context, some observations of relevance for India’s power sector.

I can think of four aspects of grid-scale battery adoption in any market: battery manufacturing, installation by developers, business models for developers, and financing by investors. It is important to shape public policy to promote these aspects.

India will need to depend on foreign battery manufacturers for some time. Also, given the dominance of China in the market, dependence on it is unavoidable. Like earlier with the BTG equipment for thermal plants, solar panels, and wind turbines, it will be prudent for India to rely on China in the early stages.

But there are lessons from those earlier examples that India must incorporate into its battery manufacturing engagements. India missed the big opportunity to leverage its massive solar demand to force wafer and cell manufacturing in the country (in a phased manner from module to cell to wafers/ingots to polysilicon), and allowed developers to import even modules. The result is that Indian manufacturers still do only module assembly using imported cells.

For a start, India must use the leverage of scale to negotiate with the likes of BYD and CATL to establish manufacturing facilities in India through joint ventures with Indian firms. These deals must include both a clearly defined trajectory of progressively increasing value addition in manufacturing, including battery R&D facilities, and the development of an ecosystem of Indian suppliers. These are matters of detail. The Indian JV partners should be supported to acquire the capabilities and strike out on their own gradually. Industrial policy incentives should be tailored accordingly, taking into account all these glide paths.

As an illustration, Brazil raised tariffs on all car imports to compel Chinese automakers like BYD and Great Wall Motors to set up plants inside Brazil. Indonesia’s policies on capturing value from Nickel extraction by banning exports of unprocessed nicket and forcing refiners and processors to establish factories locally is another example.

The Government of India must engage actively behind the scenes to ensure that the developers contract with Chinese and other battery manufacturers only on these conditions. In this regard, the large thermal and renewable energy generators like Adani Power, Tata Power, JSW Energy, Renew, Azure, Greenko, etc., should be encouraged to take the lead in this effort and develop partnerships with potential Indian manufacturers who can collaborate with the foreign battery suppliers.

Market dynamics and incentives on their own will not achieve the desired objectives. It will be required for the Ministry of Power to aggregate the battery demand on a continuing basis, bring together the foreign manufacturers and developers, and actively facilitate the negotiations.

Power sector policies should be formulated to both facilitate and make it attractive for battery developers to contract long-term with power generators and distribution companies, captive users, and also sell in the power exchanges. If not already done, the Central Electricity Authority could formulate model purchase agreements with multiple tenures for Gencos and discoms to contract with battery developers.

The industrial policy support should be tailored to achieve the manufacturing side objectives. Accordingly, it is important to target subsidies and other concessions in a manner that aligns the incentives of all sides. Given the need to progressively increase domestic value addition and build domestic manufacturing capabilities, the subsidies and concessions could be a combination of upfront (capex incentives) and recurring (supply-based) subsidies.

It is also one more opportunity for India’s private sector, especially the large companies, to step up and build a globally competitive grid-scale battery manufacturing ecosystem. The Adani Group, the standout leader in such large infrastructure projects, and with the advantages of a conglomerate spanning the entire market segment from manufacturing to generation, is best placed to show the way.

There are two other important policy requirements that governments must keep in mind. One is that of policy predictability. The commercial risks for manufacturers and developers from state and central government policies should be identified and mitigated.

For example, like renewables generation, battery costs will continue to decline in the years ahead, and there will also be technological obsolescence. This will create incentives among discoms and other contracting parties to resile from these contracts over time, as happened with solar and wind projects. Political considerations will always be around as governments change. It may therefore be useful for the Government of India to work out mechanisms to bind state governments and their contracting entities into these agreements. This will be a big risk mitigation measure for developers.

The second risk is of commercial expropriation. The infrastructure sector, apart from national highways, is dominated by a few corporate groups. India is too big a country to be able to meet its massive and rising requirements from just them. It needs the presence of several large manufacturers and developers in the infrastructure sectors. But the experiences of sectors like airports, ports, power, etc., disincentivise the mid-level infrastructure entrepreneurs to bite the bullet and assume risks to grow if they believe that the conditions allow the behemoth incumbents to swallow them up if they become successful. This must change.

No comments:

Post a Comment