A feature of China’s industrial policy has been its flexibility and innovativeness, even entrepreneurship. An example is the use of funds targeted to invest in identified sectors, targeting both industrial policy outcomes and financial returns. It also channels subsidies while neatly skirting around any WTO compliance concerns.

In his excellent book, The Rise of China’s Industrial Policy (1978-2020), Barry Naughton has written about how China has channelled massive amounts of funds to targeted strategic sectors through several Technology Guidance Funds (or Government Guidance Funds, GGFs). These funds, established since 2014, aim to establish China’s dominance in technology sectors like semiconductor chips, AI, cloud computing, robotics, clean technologies, biotech, and advanced manufacturing. They are backed by the Ministry of Finance, state banks, policy banks and state-owned enterprises.

The central, provincial, and city governments establish these GGFs with direct budget support of 20-30% and the rest is mobilised from state-owned corporations, financial institutions, and local government entities. They sometimes invest directly in innovation ventures, or indirectly as LPs in partnerships with VC/PE funds (GPs, sometimes with state-linkage), or as Fund of Funds (FoF) in sub-funds managed by the VCs/PEs and with aligned sectoral mandates.

Professional investment management firms, typically VCs, identify opportunities in the target sectors, undertake due diligence to screen and propose investments in private and public startups and firms. They also do all the portfolio management and exit planning. In all these funds, the government retains approval authority through representation in the investment committees of these funds. The investment is usually via minority equity stakes (often 5–20%) or through participation in private rounds/IPO allocations.

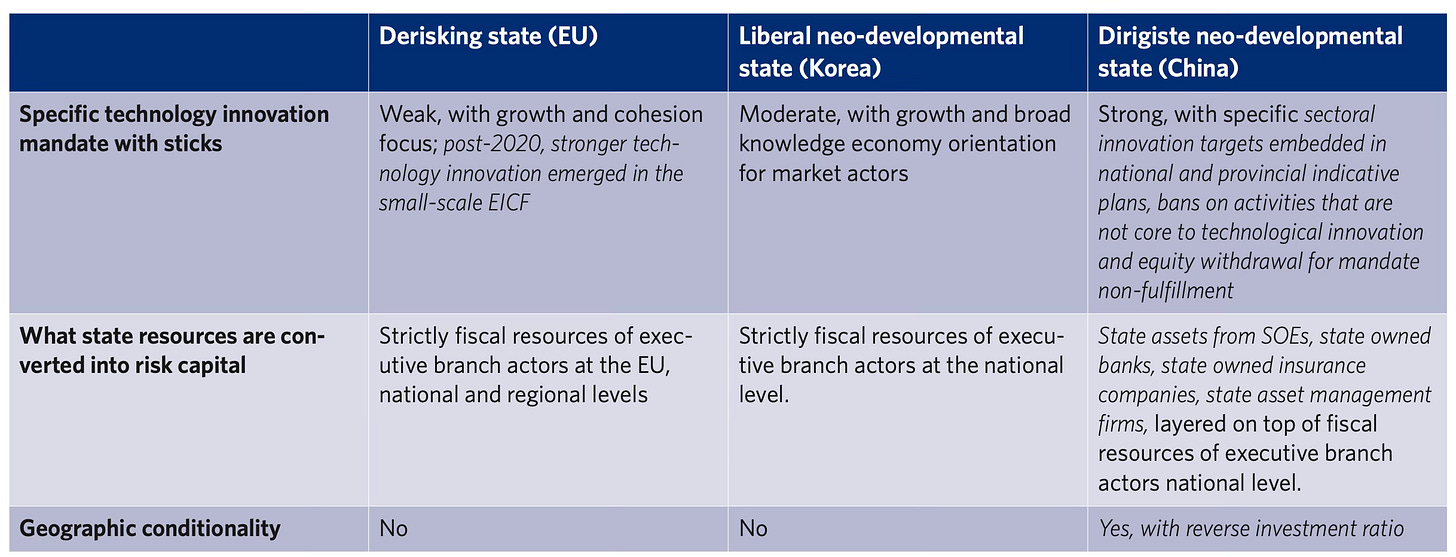

This is a good article on the topic, with the linked paper here. The paper has a table that summarises China’s approach compared with those of others pursuing industrial policy.

It finds three defining characteristics of China’s GGFs.

First, only the Chinese state remains in the driving seat, ensuring an adaptive alignment with national priorities, steering profit motives towards strategic sectoral innovation priorities integrated into the planning mechanism and disciplining sub-funds with bans on non-core innovation activities and threats of central level FoF equity withdrawal for mandate non-fulfillment… Second, when doing VC investing, only Chinese GGFs mobilize state assets from SOEs, state-owned insurance companies or state asset management firms on top of the fiscal resources of executive branch actors at national level. In this way, only China converts “stale” state assets into patient finance for productivity-enhancing technological innovations, an option available but not exercised in both Europe and Korea, where the state still owns large parts of critical sectors like energy and insurance.

Third, only GGFs have a strict geographical diversification mandate, fostering local innovation eco-systems while maintaining central oversight… the reverse investment ratio (RIR) is a mandate whereby the sub-funds invest locally at the value of between 100 to 200 percent of the equity commitment of central FoFs in the sub-funds… Another localizing requirement is “the FoF to sub-fund investment ratio,” stipulating that FoFs should contribute no more than 20 to 30 percent of the target capital for each sub-fund in which they are incorporated… The RIR increasing localization effects in both innovation and the formation of a GGF management technocracy appears to be a particularly innovative and distinctive feature of Chinese GGFs. This feature addresses regional disparities, enabling less developed areas to develop innovation hubs while fostering hypergrowth in already developed ones.

An illustrative example is the National Manufacturing Industry Transformation and Upgrading Fund.

The Economist has an article which describes this remarkable world of public-private equity in China.

More than 1,000 government-guided funds have cropped up across China since 2015. By late 2020 they managed some 9.4trn yuan, according to China Venture, a research firm. A national fund focused on upgrading manufacturing technology held 147bn yuan at the last count. One specialising in microchips exceeded 200bn yuan in 2019. Almost every city of note across China operates its own fund. A municipal fund in Shenzhen says it has more than 400bn yuan in assets under management, making it the largest city-level manager of its kind. In the northern city of Tianjin, the Haihe River Industry Fund is putting to work 100bn yuan along with another 400bn yuan from other investors... Owing to a lack of in-house investment talent, most of them have acted as limited partners (LPs) in private-sector funds... As a result, PE in China is now flush with state financing. In 2015 private-sector money made up at least 70% of limited-partner funds pouring into the industry. By the end of 2019, state-backed funds accounted for at least that much. Their dominance has only increased since then; by some counts they hold more than 90% of the money in Chinese funds of funds (ie, those that invest in other funds).

While there are no official figures, an estimate of the amounts channelled into GGFs stands in the range of $0.9-1.1 trillion, with $95-100 billion going into semiconductors (Big Funds) alone.

Noughton and others have documented the enormous wastage and failings associated with China’s trillion-dollar innovation funding programs. It appears to be a choice that the Xi Jinping administration has made in its single-minded quest to dominate strategically important sectors through its Make in China 2025 campaign.

In this context, T Surender in Livemint has a very good long read about the success of Maharashtra Defence and Aerospace Fund (MDAF). The MDAF is registered with SEBI as an AIF, and was launched in 2018 with an initial corpus of Rs 366 Cr pooled from Maharashtra Industrial Development Corporation (MIDC) (Rs 300 Cr), other government funds, and IDBI Capital (Rs 30 Cr). Its outcomes have been impressive.

Though the fund’s rollout was delayed by the pandemic, it began investing in late 2020. Over the next five years, it deployed more than ₹450 crore across 28 companies, thanks to recycling returns from early exits. By September 2025, 11 investments had been fully exited, three partially, and four firms had gone public. Together, those four companies commanded a market valuation of over ₹7,000 crore as of 22 September. An investee company executive, who did not wish to be named, said that IDBI Capital works on an internal rate of return (IRR), which represents the expected annual return on an investment, at 20-25% for its investments and offers the first right of refusal to promoters in case of an exit... What made the fund distinctive was not just where it invested, but how. IDBI Capital’s team, led by banker Amey Belorkar, knew conventional loans were a non-starter for SMEs already struggling with debt-to-equity ratios. So his team designed a quasi-equity instrument: optionally convertible preference shares (OCPS). These gave companies immediate access to cash without interest payments, while giving the fund the option to convert into equity later. Promoters could also buy back the shares at an agreed internal rate of return. The structure was flexible, patient, and crucially, non-predatory—a rarity in Indian finance...

The fund would qualify as an AIF under Sebi laws, but only companies with confirmed defence orders and at least 80% of their revenue from defence could apply. Vetting was done by Belorkar’s team, while the final investment had to be ratified by a board headed by a state bureaucrat—a structure that offered legitimacy, but also a potential chokepoint if political priorities shifted... Unlike private venture funds that chase exponential returns, the Maharashtra fund was content with steady outcomes. Its mandate was not just financial but developmental: to broaden the state’s manufacturing footprint. For SME promoters, this mattered enormously. They no longer had to fear losing control of their companies to aggressive investors... The fund also played a role beyond money. As a state-backed entity, it had access to policymakers and institutional buyers. It introduced SMEs to potential customers, advised them on governance, and guided some toward IPO readiness.

The success of Maharashtra has found resonance elsewhere to replicate.

In February, the union finance minister announced an outlay of ₹10,000 crore for startups to be funded through the Small Industries Development Bank of India (Sidbi). The money would go into a fund of funds floated by Sidbi, and would then be distributed to various venture capital funds. Sidbi Venture Capital, a fully owned arm of the bank, has a few funds that were sponsored by state governments but most focussed on social development goals such as employment and skills. Sidbi also had a fund in collaboration with the West Bengal government to invest in small enterprises but a report by the state government listed only four investments worth ₹25 crore made by the fund. In addition, the venture capital arm has startup funds for Assam and Tripura, but they are in the early stages of their investment cycles... What differed in the Maharashtra fund was that they were willing to cut large cheque sizes—up to ₹30 crore. That set apart the defence and aerospace fund… IDBI’s Belorkar says states such as Uttar Pradesh and Tamil Nadu regularly ask his team how to replicate the model. Whether they can do so without Maharashtra’s mix of timing, political backing, and institutional luck remains to be seen. Both states have already prioritized defence manufacturing, demarcating land corridors to establish new factories.

The challenge with such successes is their replication

As the tenure of the Defence and Aerospace Fund comes to a close (in October 2025), IDBI Capital will continue to manage exits. But the state has already signalled its intent to go further. A new Emerging Technologies Trust, seeded with ₹300 crore, has been registered to support companies in areas such as artificial intelligence. Once a co-investor is identified, the trust, too, will be converted into an AIF... Shortly after the Defence Fund was created, the state announced another AIF—the Maharashtra Technology and Innovation Fund—in August 2022. This was supposed to be a ₹200 crore vehicle, with the Maharashtra State Innovation Society (MSIS) contributing ₹100 crore, IDBI Capital investing ₹10 crore, and other institutions putting in the rest. Two years on, the fund has not taken off, because MSIS never brought in its share, said people involved in the vehicle...

The challenge for Maharashtra, and other states rushing to emulate it, will be to prove this is not a one-off success dependent on a handful of visionary bureaucrats and unusually patient financiers. Indeed, the real test will come when the political leadership changes, when global capital cycles turn, and when the next batch of SMEs demand their chance at the table. Will the state still back them, or will these experiments fade into the long list of well-meaning but short-lived interventions?

China’s GGFs and Maharashtra’s MDAF have important lessons for India as it embarks on industrial policy funding of innovations and indigenisation in frontier technology sectors.

I had blogged here with some suggestions on industrial policy to fund startup innovation.

Traditionally, the Government of India (GoI), through its scientific ministries, has channelled funds into innovation and R&D primarily into public institutions. In recent years, this funding has expanded in scope to include startups, but mainly in partnerships with public research and academic institutions. Direct funding to startups has remained confined to strategic sectors like Defence and Space. The rapidly emerging technological landscape and changes in the geopolitical landscape have necessitated the expansion of industrial policy to funding startups and innovators in the technology frontier and strategically important sectors.

Accordingly, the GoI has recently announced the Research, Development, and Innovation (RDI) Fund, with a Rs 1 trillion investment. It is designed as a FoF and invests through VCs and other fund managers into certain predefined sectors.

While I have not seen its investment guidelines, I’m inclined to think that the RDI will face challenges in deploying capital. For a start, the domestic VCs and AIFs investing in these frontier and strategically important sectors are tiny. Besides the domestically registered startups engaging in these areas and at Technology Readiness Level (TRL) of 7-9 (which are close to commercial deployment) are also very few. Given its size, the RDI can, therefore, be a big opportunity to catalyse the emergence of firms engaged in these important sectors.

In the early stages of this innovation funding journey, funds like RDI may have to be open to partnering with foreign funds and startups with foreign registration (for example, Indians in the US setting up companies but registering patents in the US), but all structured in a manner that maximises domestic appropriation of value and technology and knowledge spillovers. These are matters of detail.

Then there’s the issue of investment guidance. Over-constraining the investment committees with restrictions on which startups would be eligible to access these funds is a recipe for failure. Similar restrictions on investment size, co-investors and exits too are likely to come in the way of the Fund taking off.

The level of government involvement in these Committees should be dealt with caution. This is important not only on professional considerations (the public nominees are likely to skew the Committees away from risky investments) but also because many of these investments, especially in the early years, are likely to fail given the sparse domestic innovation landscape, thereby inviting post-facto scrutiny, especially if there’s close government involvement.

In this context, while frontier innovation will remain challenging and risky, a prudent investment promotion opportunity is that of indigenous design and development of important components and products that are all currently imported. Efforts at indigenisation are an essential requirement to develop the industrial base and ecosystem to support frontier innovation. Such investments can be a good feed-in to the Production Linked Incentive (PLI) scheme (and its variants), which promotes indigenous manufacturing.

State governments should proceed with caution on such funds. These funds require a strong institutional basis, and the political economy of state governments is not conducive to forming such foundations. Politically driven investments and corruption are never far away in such environments, thereby leaving them vulnerable to controversies and scandals.

No comments:

Post a Comment