Much of what is written in the media, including in this blog, about China is about its spectacular economic growth to catch up with the US, and its manufacturing dominance.

Rana Faroohar has a contrarian piece which makes the rare bearish case on China. She points to three facts about China in support.

First, despite new pledges to raise consumption, the mathematics and politics of doing so are as tricky as ever. Second, while global diplomacy is now Beijing’s game to lose, it has made many fewer gains than it should have so far, given the low-hanging fruit. And third, autocracy remains a hard sell globally, which will make it difficult for China to ever replace the US (or even Europe) in terms of soft power.

I had blogged here about post-peak China.

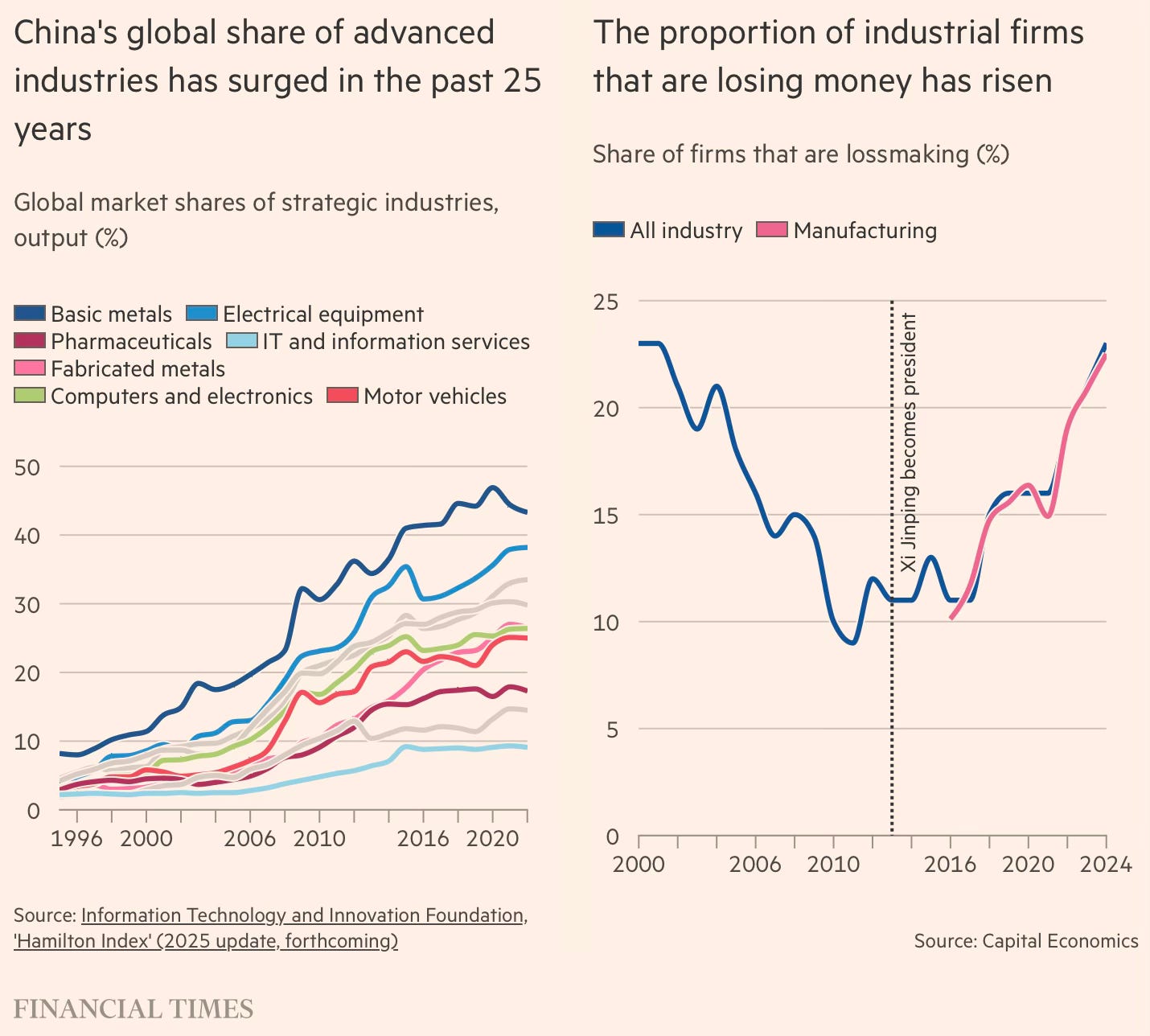

On this track, there’s an important paradox about China. Even as it has assumed leadership positions in innovations across sectors, its economic productivity growth has been slowing down. Tej Parikh has a set of excellent graphics that tell the story. This blog will explore this in greater detail and see how it could potentially constrain the country’s growth prospects.

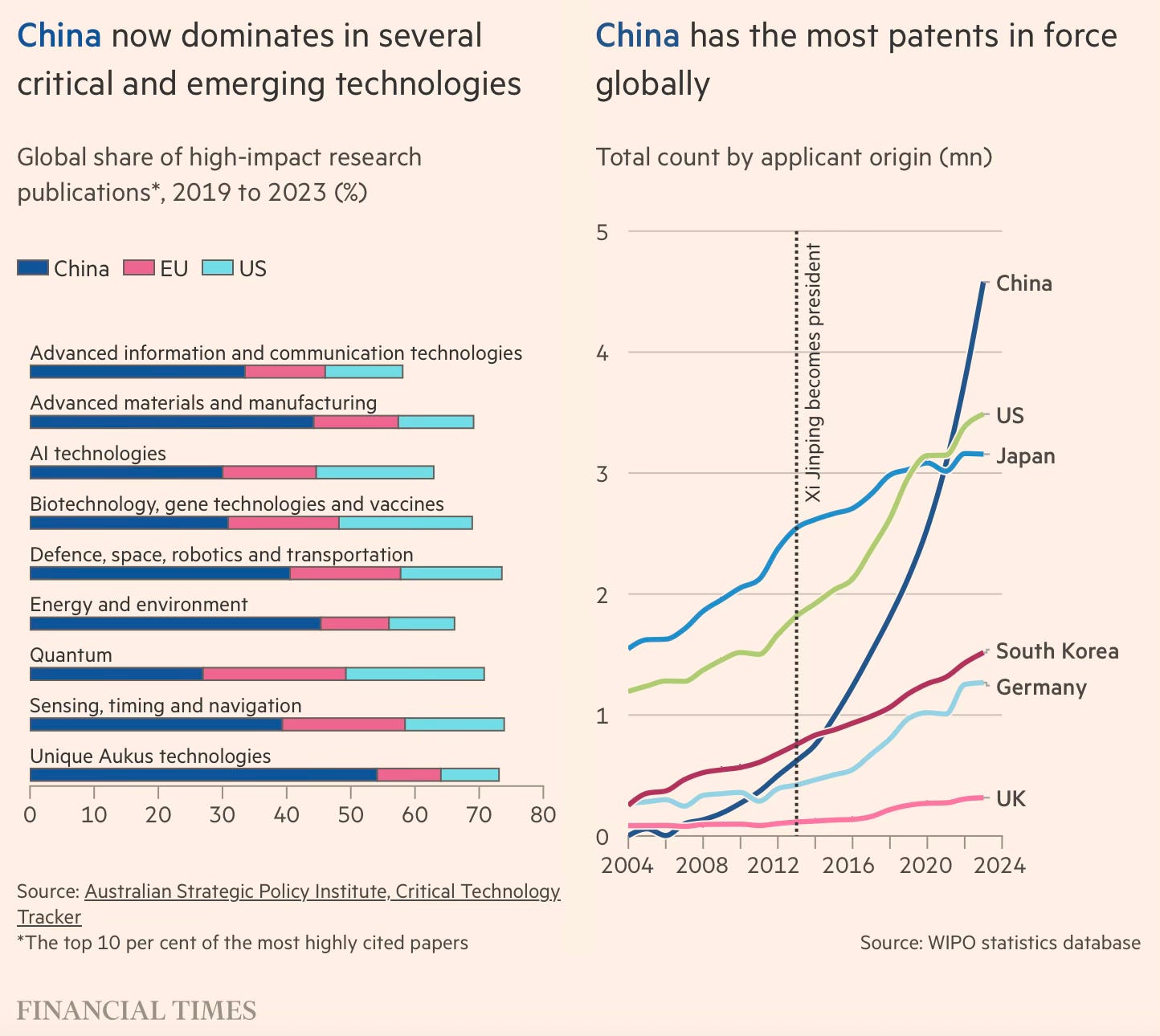

According to the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, China became the global leader in 57 out of 64 critical technologies between 2019-23, up from leadership in just 3 between 2003-07. It leads today not only in manufacturing EVs, batteries, renewables, etc., but has almost caught up with the West on AI, quantum technologies, and biotech.

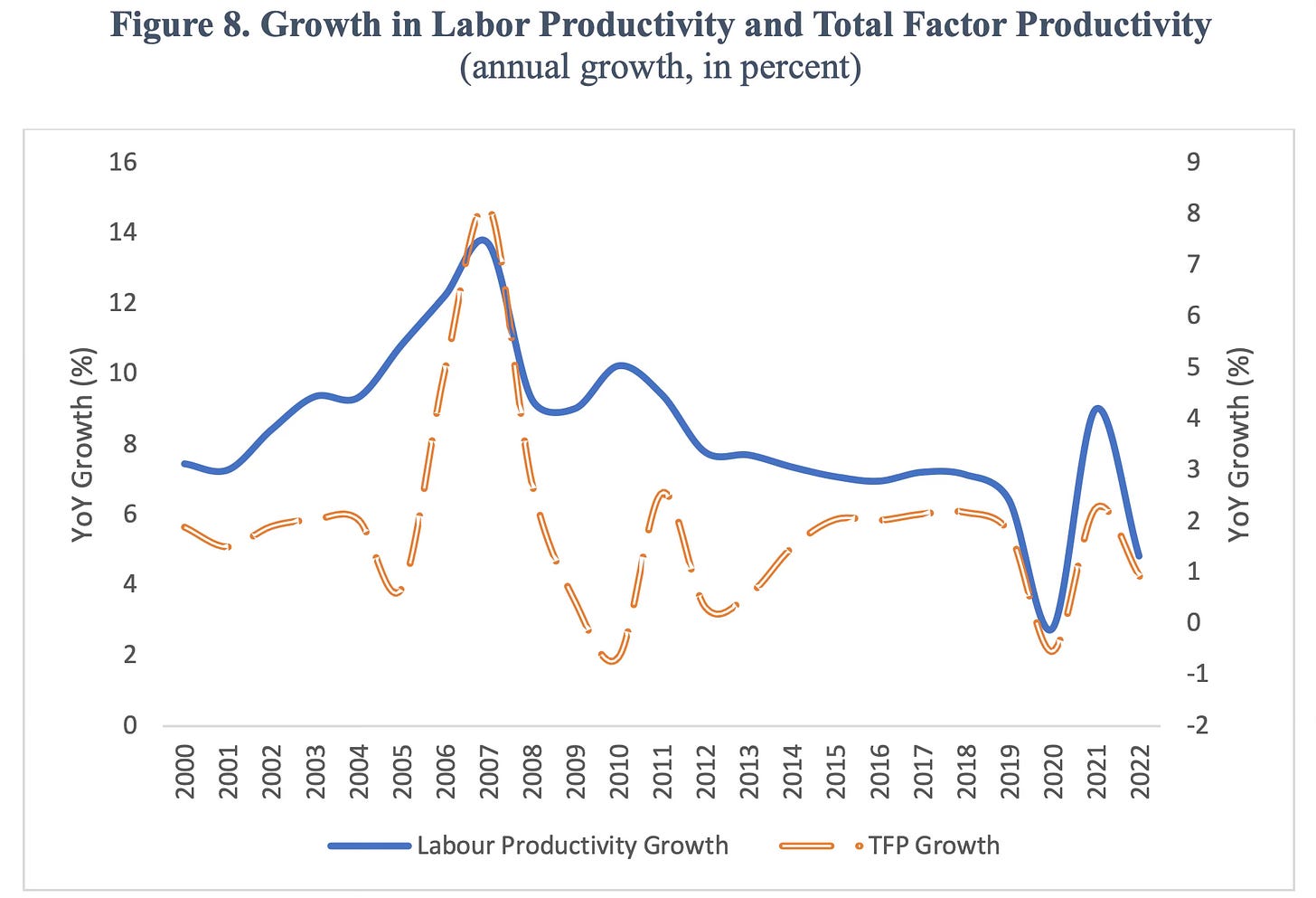

But this leadership in innovation and manufacturing has not translated into productivity growth, where its TFP has slowed down considerably and is now grossly underperforming the East Asian miracle economies.

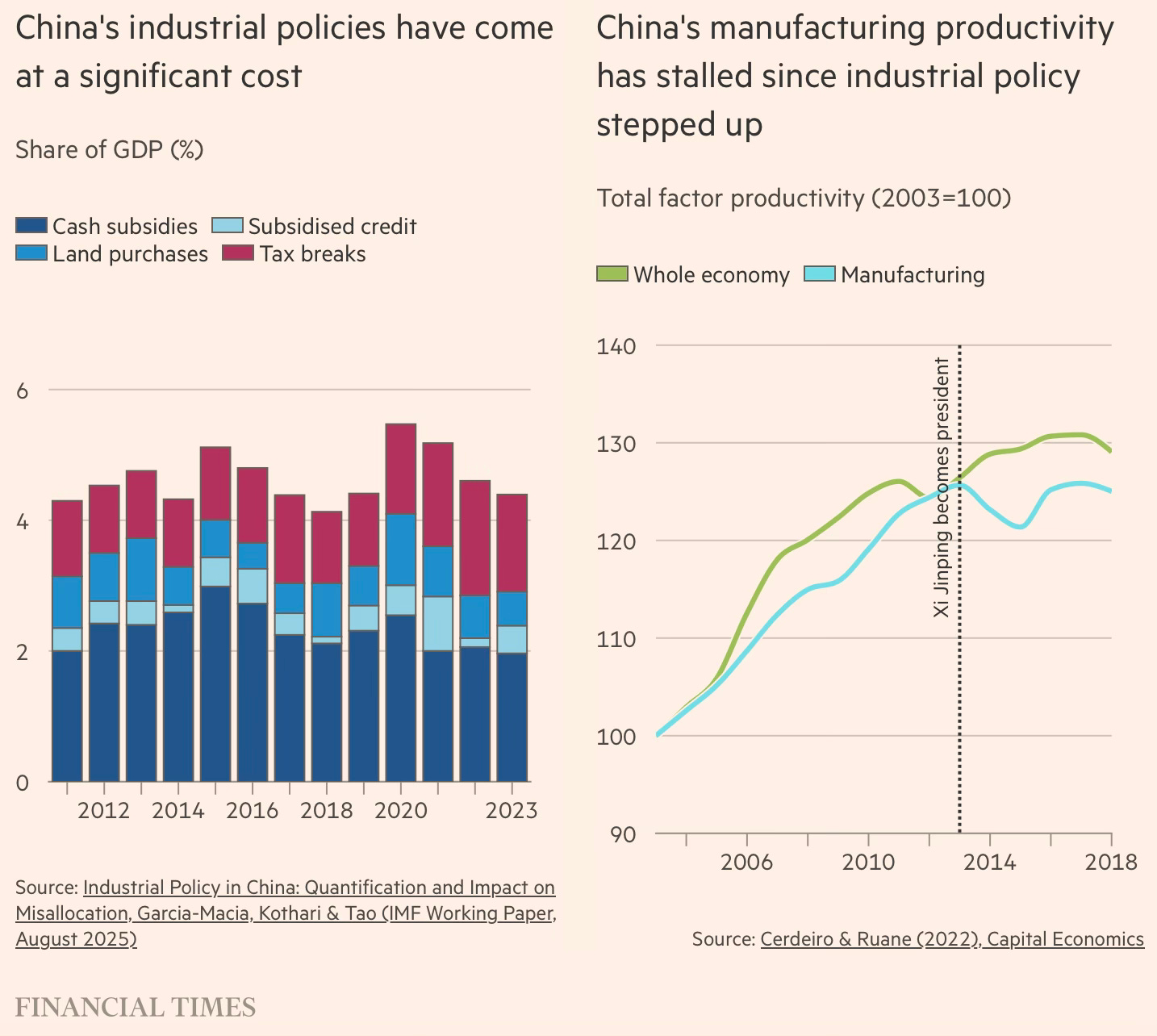

China’s industrial policies may have misallocated resources in a big way, thereby creating excess capacity, deflation, and keeping alive poor performers. IMF economists estimates that these subsidies, estimated at 4.4% of GDP in 2023, may have cut its TFP by 1.2% and GDP by 2%. They have tended to flow to better-connected firms, and raised entry barriers, thereby misallocating both talent and finance.

For each success story like BYD or Huawei, there are countless others who are bleeding subsidies, making losses, and will collapse. Analysis by ASR finds that over 25% of listed non-financial firms had earnings before interest and tax-to-interest coverage ratio below 1 in 2024, up from around 10% in 2018.

China’s paradox of the co-existence of excellence in manufacturing innovation with declining productivity growth is a reflection of the inefficiencies in its industrial policy. China’s much vaunted manufacturing dominance has come at a prohibitive cost in terms of misallocation of resources and talent.

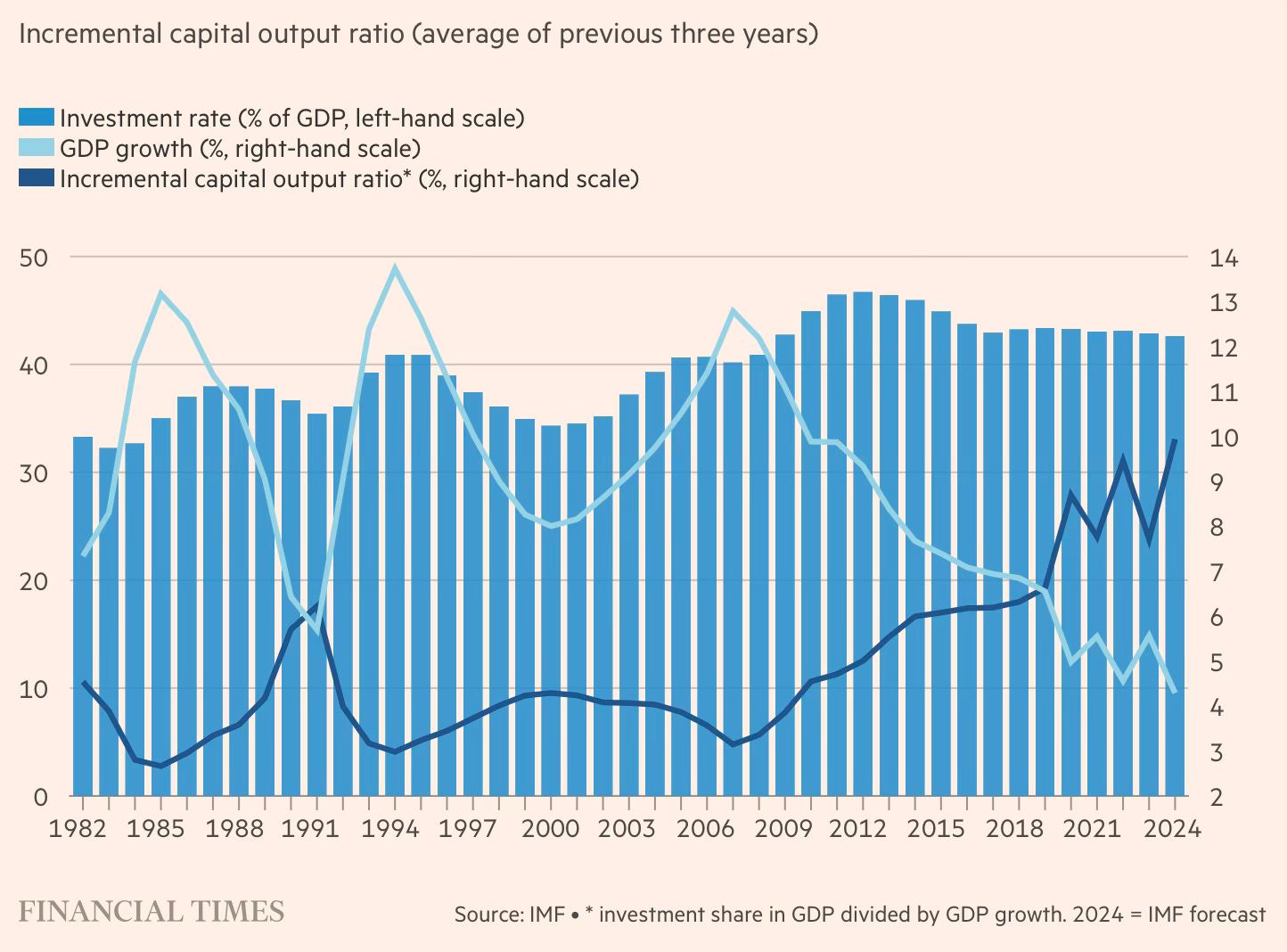

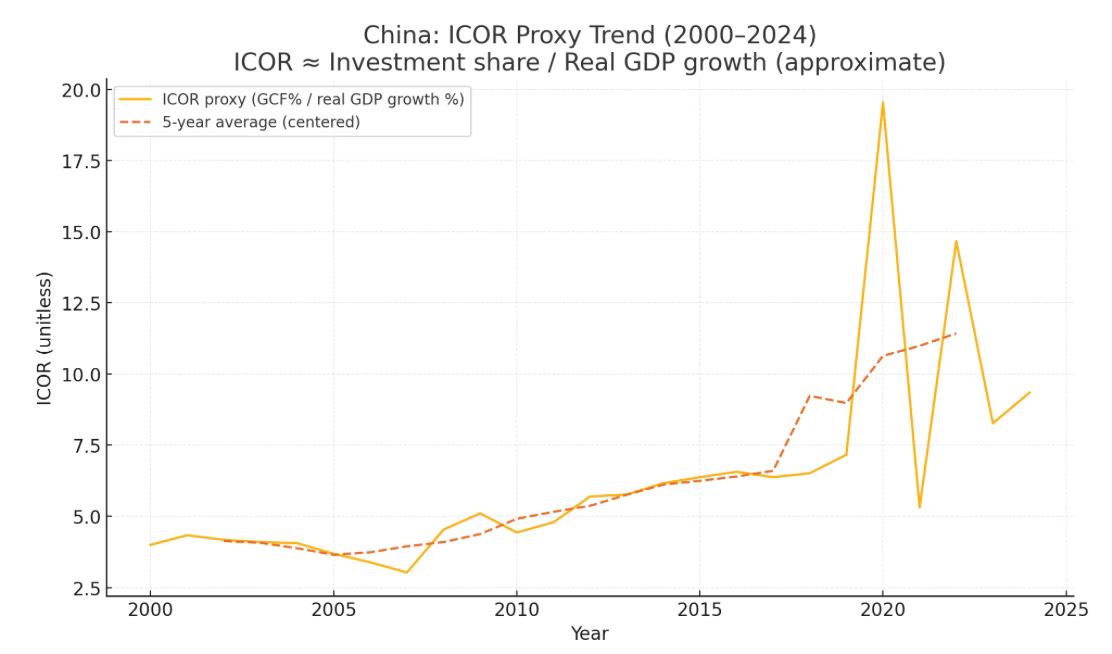

I have blogged here pointing to China’s sharply rising incremental capital output ratio (ICOR). Even as investment has been range-bound at 43-45% of GDP since before the global financial crisis, the ICOR has nearly tripled from below 3.5 to touch 10. This period has also coincided with economic growth declining precipitously from above 12% to just 4%. As the graphic shows, high investments rates brings ever less growth.

Here is an updated version of the ICOR trends generated from the WB WDI series for investments and GDP growth.

This misallocation has led to the perpetuation of inefficient firms, the accumulation of massive excess capacity, and the excessive leveraging of local governments and firms. In general, it has also created an economic system that is primed to maximise output with little regard for demand, continuously capture and expand export markets in a beggar-thy-neighbour dynamic, and is oblivious to policies required to boost domestic consumption. This trend is also encouraged by the country’s politico-bureaucratic system, where leadership at provinces, towns, and counties are evaluated on performance (and promotion up the party hierarchy) based on expanding economic output.

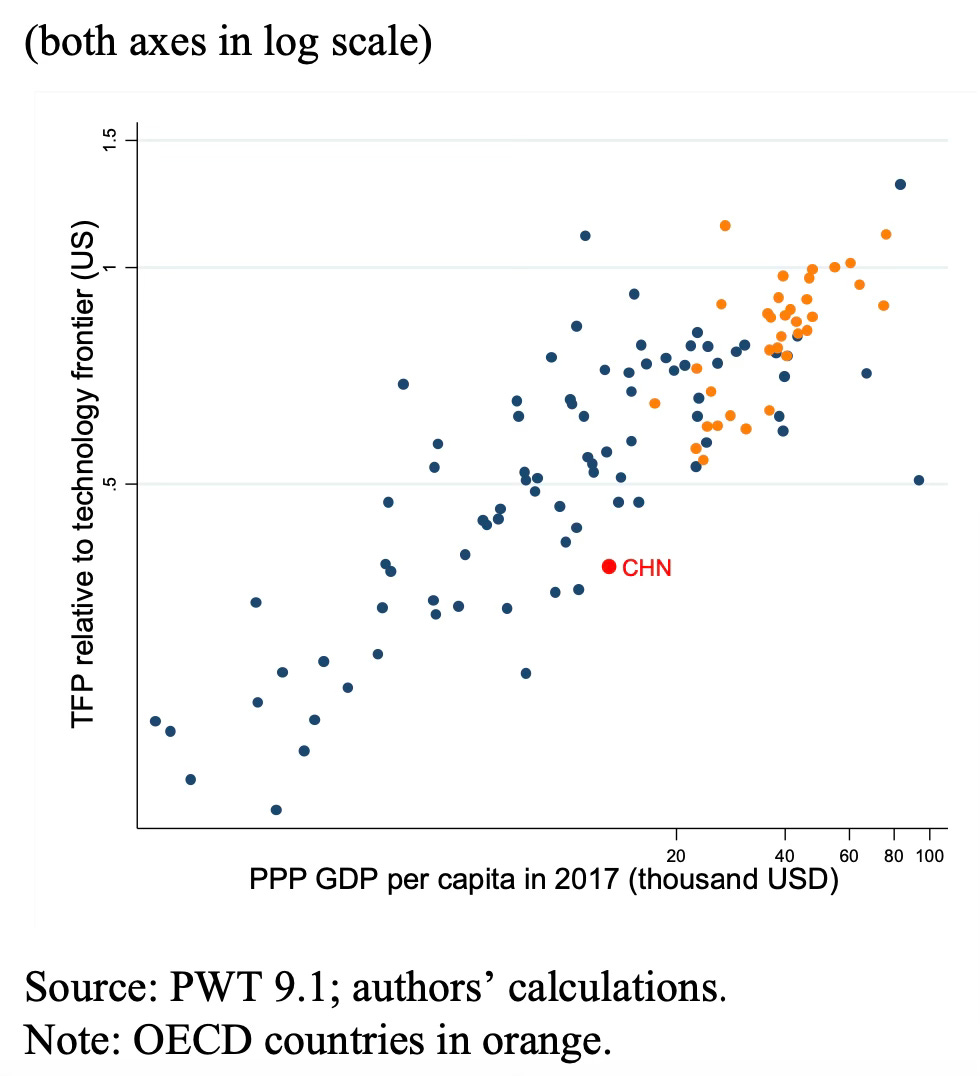

There are at least three hard stops to this model. One is the importance of productivity growth in maintaining reasonable GDP growth in an economy faced with a shrinking labour force, an increasing share of the services sector in the economy, and declining efficiency of investment. An IMF working paper shows that China TFP compared to the technology frontier (US=100) in 2017 lagged even middle-income countries.

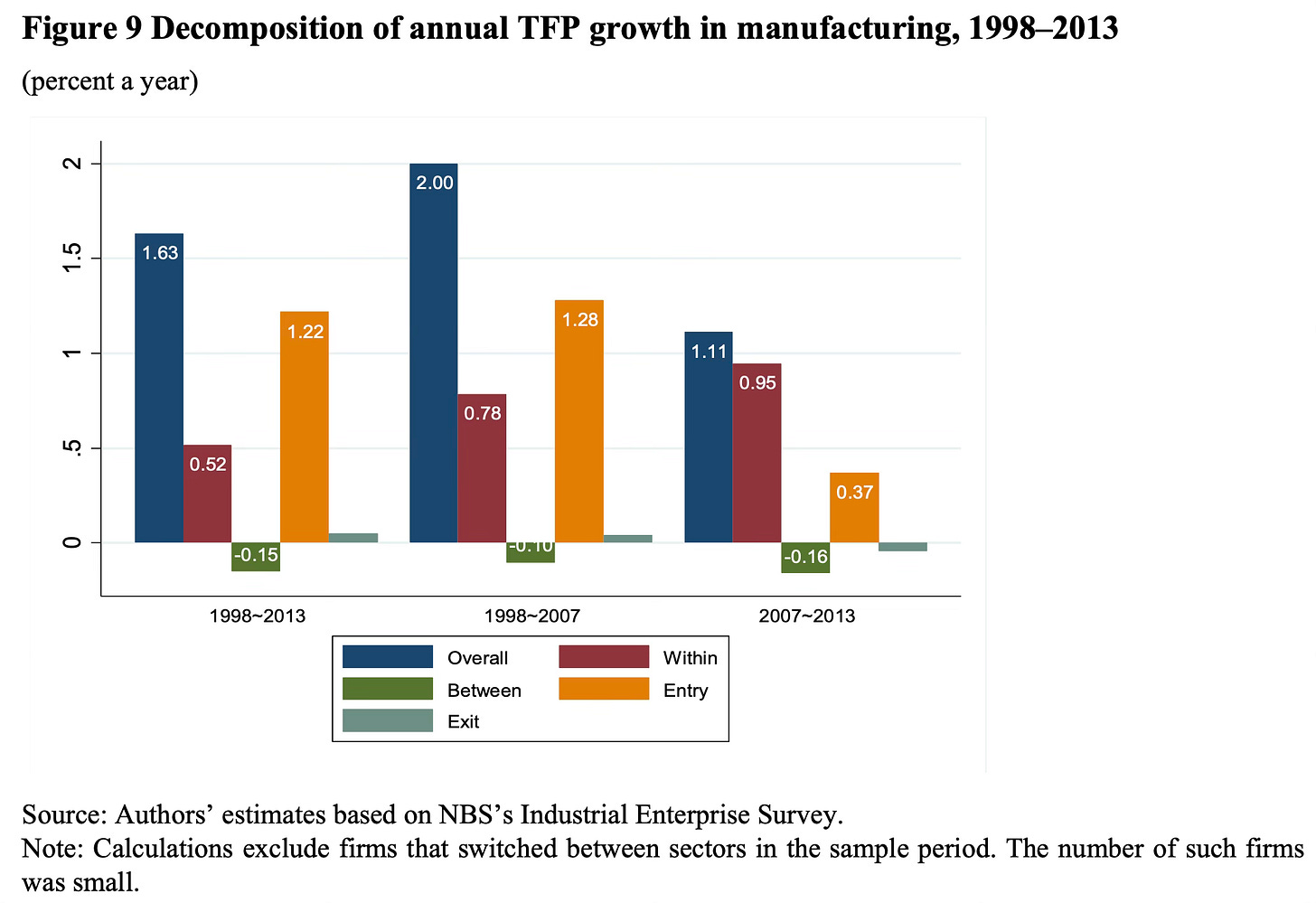

The paper points to a major problem of limited market entry and exit and lack of resource allocation to more productive firms in manufacturing.

Over 1998–2013, most of the increase in productivity—two-thirds—came from the entry of new firms… The other primary source of growth was improving productivity of incumbents, which contributed 40 percent. Over the entire period, firm exit contributed negligibly to manufacturing productivity growth, reflecting one of several possibilities. Poorly performing firms either did not exit or exited but accounted for only a small percentage of aggregate output. Or the productivity of some firms that exited was average or better. Similarly, there were no gains from reallocating resources (labor, capital, and intermediate inputs) to more productive firms, which would have increased aggregate productivity, all else equal. In fact, the contribution was slightly negative. In advanced countries, this is the most important source of productivity growth, and thus stands out as a possible major source of future productivity growth in China. After 2007, average manufacturing productivity growth in China decreased almost by half. The most important reason for the decline was that the contribution of better entrants disappeared. In some sectors, the contribution of new entrants was actually negative, implying that these firms entered the productivity distribution lower than the sector average.

As I have blogged in China Updates, there are reasons to argue that these trends on exit have worsened in recent years,

Eswar Prasad has highlighted China’s productivity problem. The country’s TFP growth (RHS) has been stagnant at about 1 per cent over the last decade.

He has explained why this is a big problem.

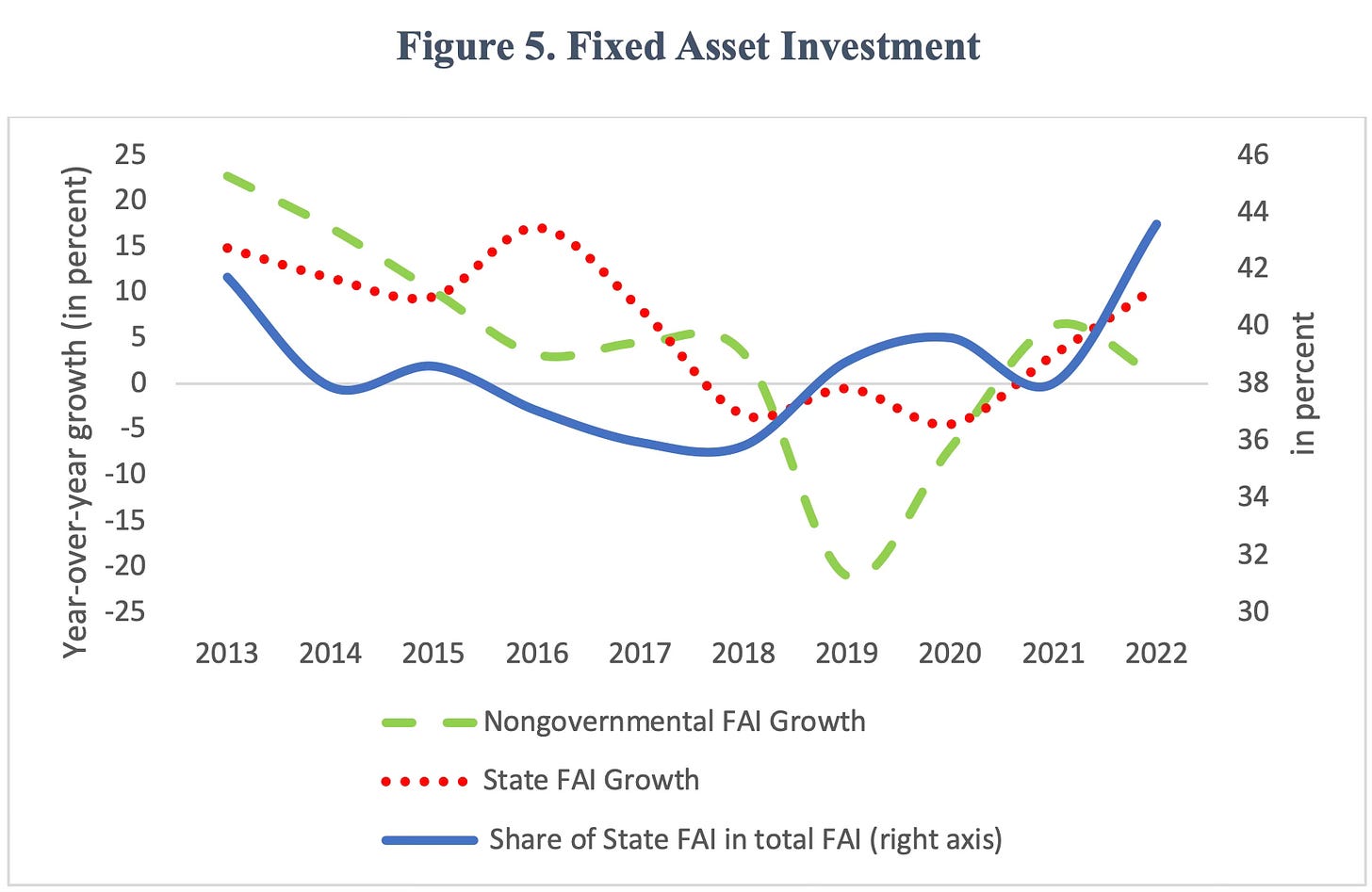

China’s capital to labor ratio is only about 28 percent that of the United States. However, recent investment has been driven by the public (state) sector rather than the nongovernmental sector. In 2022, for instance, state investment amounted to 44 percent of total fixed asset investment, a significant increase relative to the corresponding ratio of about 36 percent during 2017-2018… in China state-owned enterprises, which have collectively received a disproportionate share of bank credit, have typically not generated strong returns on those investments. The recent collapse in nongovernmental investment growth, with state investment accounting for nearly all of the growth in overall fixed asset investment in 2022, is a sign that private businesses might be wary of increasing investment when they see the economic and political environments as unfavourable. Moreover, China’s capital to output ratio is in fact about 50 per cent higher than that of the United States. This reflects lower levels of total factor productivity (TFP) and human capital in China relative to the United States. This implies that increasing investment might not be the optimal way to generate growth.

This is another useful paper on China’s productivity paradox.

Second is the ongoing backlash from export markets. Chinese exports to the US are already shrinking, and the same will be true for other advanced economies in the days ahead. As I have blogged on multiple occasions, and Arvind Subramanian and Shoumitro Chatterjee have written, China’s exports are now threatening to destroy the industrial bases of developing countries.

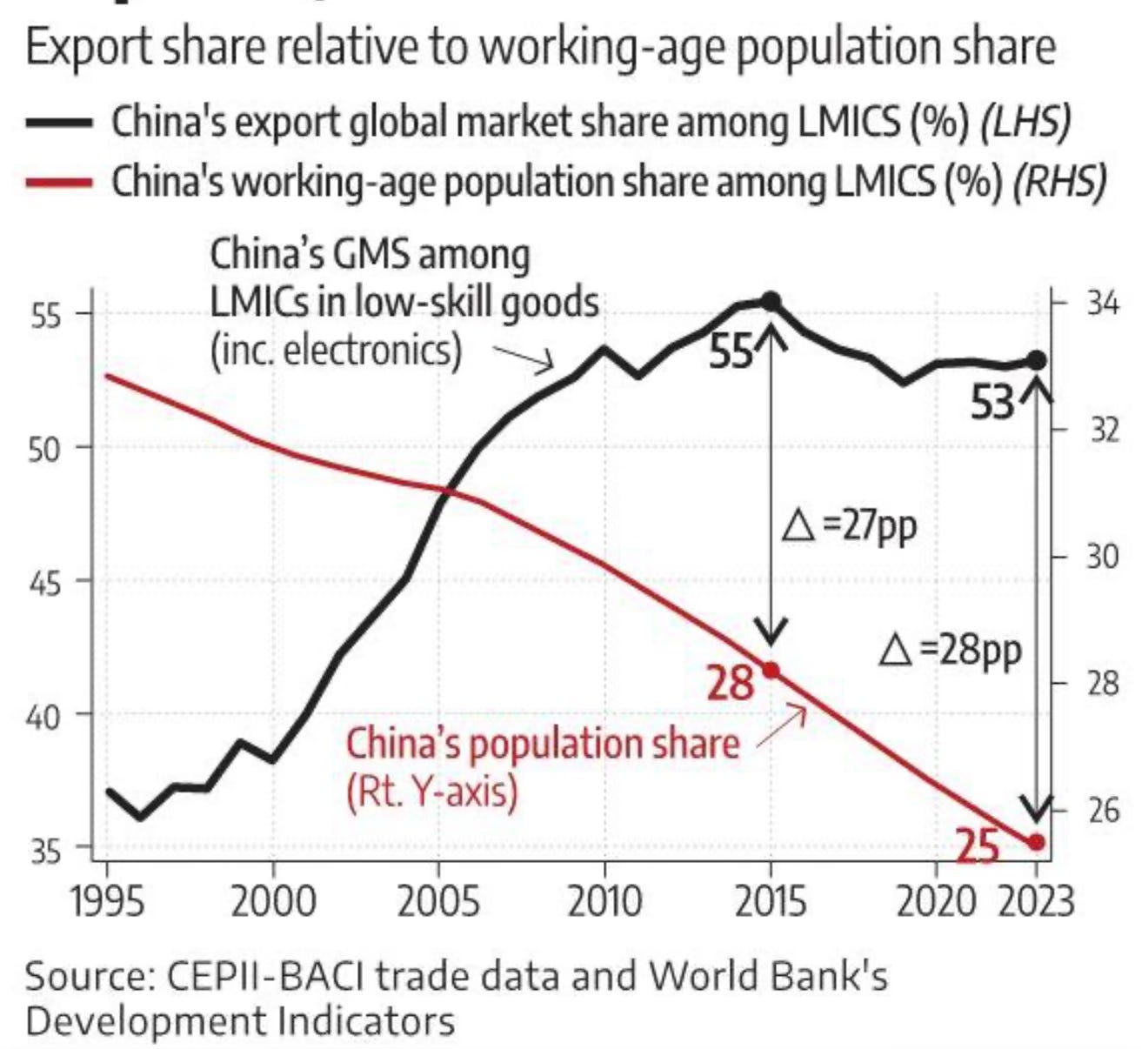

Today, China’s manufacturing trade surplus stands at roughly $2 trillion, about $1.4 trillion of which comes from low-skill goods… Chinese imports still account for about 1.5 per cent of the West’s gross domestic product (GDP)… Accounting for almost 4 per cent of LMICs’ combined GDP, the import shock from China represents a larger (and growing) share of their economies than imports of high-skill goods do in developed countries… compare China’s share of low-skill exports among LMICs to its share of the global workforce… The wedge between China’s export share and its labour-force share — roughly 28 percentage points — suggests that China continues to occupy “excess” export space that could otherwise support tens of millions of manufacturing jobs in poorer economies.

Finally, there is the investment model hitting the debt ceilings for corporates and local governments. Since 2010, government debt has risen from 34% of GDP to over 86% today, and this is most likely a gross underestimate given the large value of off-balance sheet debts of local governments in the form of local government financing vehicles (LGFVs).

Household debt has risen from 18% in 2009 to 62.5% in 2024, and more than doubled over just the last decade. This is amplified by the fact that property accounts for nearly 60% of household wealth in 2019. These, coupled with restrictive regulations like the hukou system and deficient social safety nets, mean that household consumption, which is already low in China’s share of national output but whose growth is the only way for China to reach a sustainable growth path, is likely to remain subdued.

The government somehow (perhaps more by luck and throwing the kitchen sink at the problem) managed to stave off a financial crisis from the popping of the real estate bubble in 2020-21. It has instead diverted the credit flows to manufacturing to build up capacity and capture foreign markets.

The fact that most major banks are state-owned adds one more layer of distortion by allowing the government to keep infusing credit to failing firms to prevent systemic crises. This happened in the aftermath of the real estate bubble bursting, especially when the Evergrande crisis threatened spillovers and a meltdown. This is likely to recur with the manufacturing firms in green technologies and the like.

It can be said with confidence that if we were talking about any other country, the macroeconomic indicators and their trends, and the dominant economic and political environments, would clearly point to an imminent economic slowdown or crash. The market would be full of shorts for the economy. As Eswar Prasad writes,

The underpinnings of China’s growth seem fragile from historical and analytical perspectives. Things that must end do often end suddenly and in unpredictable ways.

However, in the case of China, we need to take into account the government’s rich track record of adept handling of potential crises and vulnerabilities. But even expertise and luck have their limits.

No comments:

Post a Comment