This post will continue the exploration of China’s economic and political vulnerabilities as geopolitical tensions rise with the US and the West.

A narrative has taken hold that China’s manufacturing dominance is a source of vulnerability for the rest of the world and an instrument that the country can weaponise to promote its strategic interests. This weaponisation of product manufacturing overlooks the economic dependence of the exporting country on global markets, especially for an economy where domestic consumption is subdued, exports are a major share of manufacturing capacity, and the manufacturing supply chain is localised in product clusters.

The last part is especially important insofar as it means that any reduction in exports can immediately inflict locally concentrated pain in terms of assembly lines idling, factory shutdowns, and job losses. Discontent arising from this is more salient and politically troubling than those pains that are diffused economy-wide.

The political economy sting of the China shock that David Autor and Co. have documented owes primarily to the concentrated nature of its impact on certain industrial towns due to factory closures and job losses due to imports from China of those specific products. In the aggregate sense, at 2-2.4 million job losses in the 1990-2007 period, its impact on the US economy would be marginal.

Manufacturing supply chains are mostly concentrated in clusters. Typically, most of the manufacturing of a product will come from a few clusters. This means that the manufacturing capabilities and base are heavily localised, sometimes in just one or two locations. This leaves the manufacturing base deeply vulnerable to being eliminated when faced with export competition, like that coming from China. Instead of an incoming missile physically destroying the main weapons arsenal, the incoming exports are closing down the main centre of manufacturing of that product and forcing the product ecosystem to disintegrate.

The converse of this phenomenon is China’s vulnerability. China is especially known for the cluster nature of its manufacturing ecosystems, where entire towns are monocultures of specific products. There are more than 500 such specialised towns, with some being responsible for 63% of world’s shoes, 70% of its spectacles, and 90% of its energy saving lamps.

This approach is like that of a country that has concentrated its weapons systems into specific locations, thereby leaving them vulnerable to single air strikes that can take down entire locations.

Sample this about coffin-making,

The coffin-makers of Zhuangzhai, a leafy township of 100,000 people in the eastern province of Shandong, are a case in point. Between them, Zhuangzhai’s three main manufacturers export 740,000 coffins annually, almost all of them to Japan. With just under 1.4m deaths in Japan last year, that gives one Chinese township something around half the Japanese coffin market.

This is a source of immense strength. It creates an unmatchable manufacturing eco-system. So production is not easily replaced, even if Japan wants to diversify away from China,

The largest local firm is Yunlong Woodcarving, which ships 20,000 coffins to Japan each month. Its 56-year-old founder, Li Ruqi, has coffin-making in the blood... In 1995 his firm began supplying a Japanese coffin-maker with panels decorated with phoenixes and lotus flowers. Most were carved from the wood of the paotong, which grows all around Zhuangzhai... Some Japanese clients did try sourcing coffins in Vietnam and Indonesia, he concedes. But they found that workers in South-East Asia lacked “discipline”, so returned to Shandong. His corner of China has paotong trees, skilled labour and trusted suppliers. “Price-wise, talent-wise, this place is pretty far ahead,” he says.

However, it is also a source of risk, as seen by the plight of the bra-making town of Gurao. How many Guraos would it take to trigger domestic discontent?

This manufacturing strategy has consequences that go far beyond the domestic polity. An illustrative example is that of tomato paste, whose exports to the main customer, Italy, and Western Europe, have collapsed this year after allegations of using forced labour and misleading origin labelling by companies. The Italian farming association led a high-profile campaign against the Chinese paste costing less than half of that made domestically, and the adulteration of premium Italian-made paste with imported paste.

Tomato News, which tracks the global processing industry and trade, estimates China has a stockpile of 600,000 to 700,000 tonnes of tomato paste — equivalent to roughly six months of its exports… While China’s total tomato paste exports by volume fell 9 per cent year-on-year in the third quarter of 2025, sales to western EU countries dropped 67 per cent, and Italy’s purchases were down 76 per cent, Tomato News said…Chinese customs data shows the value of processed tomato exports to Italy plunged to less than $13mn in the first nine months of 2025 from more than $75mn in the same period of last year… China processed 11mn tonnes of fresh tomatoes into paste in 2024, up from 4.8mn tonnes in 2021, according to Tomato News. With European demand collapsing, the Asian nation has more than halved the volume of the fruit processed to an expected 3.7mn tonnes this year.

The western Chinese region of Xinjiang, populated by the minority Uyghur community, has become a major centre for tomato cultivation and processing in recent years.

The article is a great illustration of how parts of the Chinese economy have emerged primarily to serve export markets.

Tomatoes, which were introduced to China after European colonisation of the Americas, play a relatively minor role in Chinese cuisine. One of the Chinese names for the fruit can be translated as “foreign aubergine”, while the other means “western red persimmon”. But China has turned Xinjiang, home to the mainly-Muslim Uyghur minority, into a low-cost, export-oriented tomato paste production hub spearheaded by large state companies, one of which is a subsidiary of the paramilitary Production and Construction Corps that helps run the region… Xinjiang’s tomato industry has been dogged by allegations of use of forced Uyghur labour. In 2021, the US banned tomato paste imports from Xinjiang, citing such concerns… A BBC documentary last year alleged some Uyghur prisoners and detainees were forced to harvest tomatoes that may have wound up, via Italy, on UK supermarket shelves. The report prompted retailers fearful of a scandal to put pressure on Italian processors not to use Chinese paste.

Such purely export-focused manufacturing development will be deeply strained as the backlash against cheap Chinese exports spreads from the US and Europe to developing countries. China is certain to face a reverse China shock arising from the squeeze on exports to the rest of the world.

This dynamic comes on top of an investment boom that is clearly flagging slumping. Fixed asset investment shrank a record 1.7% in the first 10 months of the year, with Bloomberg Economics estimating investment dropping by as much as 12% in October, the fifth successive monthly decline.

This is on top of stagnant infrastructure investments, declining property investment, and slowing growth and outlays in manufacturing. Infrastructure investments have slowed as local governments have been left with declining property market revenues and have focused on deleveraging.

The property market crisis has been a major drag. The property market has a disproportionate impact on the economy, contributing directly and indirectly to between 20-25% of the GDP, being the primary financing source for local governments, and the main source of household wealth. The negative wealth effect from the property market slump has been a dampener on consumption. Worryingly, the property market has been on a continuous downward trend since the beginning of 2021.

The hostile external environment has squeezed manufacturing investments. The manufacturing sector has been experiencing the phenomenon of “involution,” characterised by price declines resulting from intense competition and excess capacity. Noah Smith has a good description of the associated problems.

This so-called “involution” results in misallocation of capital, reducing productivity growth and ultimately slowing GDP growth. By destroying profit margins for even the best-run Chinese companies, involution damages their ability to invest for the future. The excessive corporate competition from involution contributes to China’s overwork problem, because it gives companies an incentive to work their employees to the bone in order to get a competitive edge. And worst of all, involution drives down prices, causing deflation that exacerbates the value of the debt left over from the property bubble.

While sectors like electric equipment and machinery, solar panels, and batteries have seen declines in investments, they continue to stay elevated in the EV industry. In fact, the EV industry looks set to be ground zero for a manufacturing implosion arising from intense competition, massive excess capacity, and low margins.

Bloated by excessive investment, distorted by government intervention, and plagued by heavy losses, China’s EV industry appears destined for a crash. EV companies are locked in a cutthroat struggle for survival… Dunne Insights, a California-based consulting firm focused on the EV industry, counts 46 domestic and international automakers producing EVs in China, far too many for even the world’s second-largest economy to sustain…To woo customers in this crowded market, China’s EV companies have been slashing their prices, making profits slim. In most economies, the market would sort out this mess by culling the weakest players…In China, state support or ownership of automakers extends the life of struggling businesses. Local governments are also reluctant to lose the jobs they bring, so officials prop up unprofitable companies. The city of Wenzhou recently helped arrange financing for an EV maker called WM Motor, to get the company’s local factory humming again. The city of Hefei rescued the EV start-up Nio in 2020, but the publicly listed company continues to lose money—$1.6 billion in the first half of this year.

Despite these losses, the government has so far been unwilling to pull the plug on EV investments since it sees EVs as a great opportunity to fortify China’s global manufacturing dominance.

China’s state-led EV program, by design, has been predatory. By subsidising these companies, China sought to edge out more established automakers in the U.S., Europe, and elsewhere. Beijing’s economic planners are willing to sacrifice something as frivolous as profitability to fulfill their dreams of building an internationally competitive car industry. China “sustains a lot of inefficiency at home in order to dominate industries and markets globally,” Dunne told me.

This is one more illustration of Beijing’s resolve to use its manufacturing dominance to expand its global power.

As I blogged here, illustrating the capital efficiency and productivity problems, there are hard limits to such inputs and an investment-driven growth model. Even China can’t sustain direct subsidies to manufacturing, which makes up 15-35% of the profits of companies. Any pathway for sustainable economic growth must involve raising the remarkably low consumption share of economic output.

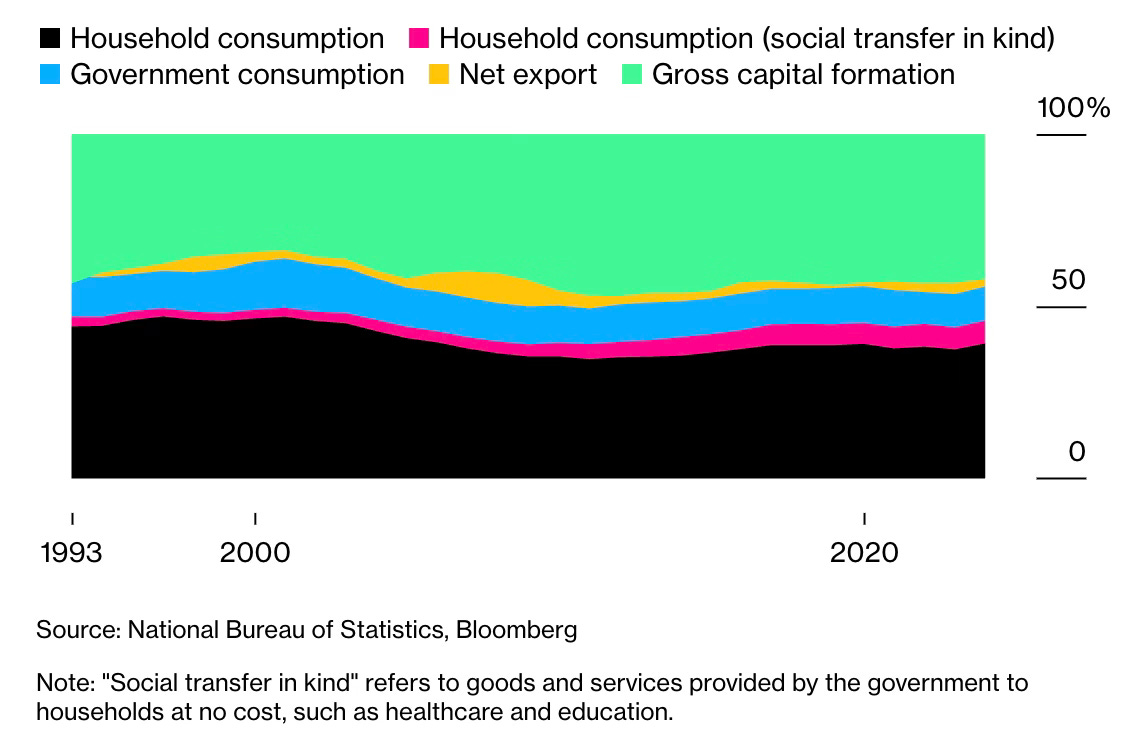

The disproportionately low share of domestic consumption, at less than half the economic output, has been a persistent distortion in the Chinese economy.

Rebalancing the economy away from investment towards consumption is the only way for an economy as large as China to build the foundations for sustainable economic growth. But the Chinese government has consistently avoided treading into policies to boost domestic consumption. This is all the more surprising now, given that consumer confidence has remained stuck at the lows it plummeted in the aftermath of the COVID-19 lockdowns in early 2022.

This time too, Beijing has predictably stepped in with supply-side stimulus measures of various kinds. As the Bloomberg article writes, “A total of 1 trillion yuan in stimulus has been approved since the end of September to spur capital expenditure and replenish local coffers, with the effects likely to become more evident in the coming weeks.”

Finally, all these problems must invariably collide with the domestic political economy and strain the social contract between the Communist Party and the Chinese people. In a recent article, Helen Gao has a nice description of the contract.

China has long thrived under an unspoken social contract: The Communist Party granted the people more freedom to improve their livelihoods in return for political obedience. To many Chinese, the government is no longer holding up its end of the bargain.

She describes the internal situation in China.

Internationally, China looks strong. It is America’s only rival in terms of the power to shape the world… That muscular facade is punctured here in China, where despair about dimming economic and personal prospects is pervasive. This contrast between a confident state and its weary population is captured in a phrase Chinese people are using to describe their country: “wai qiang, zhong gan,” roughly translated as “outwardly strong, inwardly brittle.” Many now feel that the very state policies that have made China appear strong overseas are hurting them. They see a government more concerned with building global influence and dominating export markets than in addressing the challenges of their households…

Youth unemployment is so high that last year the government changed its calculation methodology in a way that produced a lower number. Even the new figure remains alarmingly high. An estimated 200 million people get by in precarious careers in a gig economy. Consumers, many of whom have seen their net worth shrink in an intractable housing market crash, are cutting back on spending, trapping the economy in a deflationary spiral. The sense of economic insecurity is leading people to forgo marriage and starting families, worsening a national decline in population. Popular frustration also is sharpening the divide between the haves and the have-nots — hardening public resentment against those who are perceived as parlaying economic or political connections into opportunity while most people face dwindling prospects. And mental health problems are believed to be rising, as evidenced by a spate of indiscriminate stabbing sprees and other violent attacks in the past couple of years.

Noah Smith points to similar findings from a PBoC survey.

Chinese households became more pessimistic last quarter and their view of the jobs market fell to the worst ever, according to a survey by the central bank…Consumers turned increasingly negative about income, employment, and prices in April-June, the poll showed… The data also revealed that people’s willingness to consume dropped to the weakest since the outbreak of the pandemic, with almost two-thirds of respondents saying they want to save more, while an employment index fell to a record low…The data also showed a shrinking percentage of respondents expecting consumer and housing prices to rise.

In this context, when history is written, the Xi-Trump trade deal of October 2025 that postponed tariff escalation by a year may well come to be counted as a gift to China, a massive Trumpian self-goal. While the dominant narrative in the US and elsewhere was of a victory for Chinese strategy and diplomacy, the real story may well be one of the US blinking first and failing to call the Chinese bluff. It was an opportunity lost for the US to tighten the screws on China at a time when its economic and political faultlines were clearly visible.

No comments:

Post a Comment