I have blogged on multiple occasions, pointing to the perils of excessive reliance on experts.

Central banks are considered the epitome of technocracy in economic policymaking. Much has been written about how independent central banks manned by technical experts and using technical rules like the Taylor Rule and inflation targeting have tamed inflation and ensured macroeconomic stability. Never mind the several questions and disputes surrounding this narrative. I have blogged here, here, here, and here, trying to place central bank independence and competence in perspective.

Since the global financial crisis, there has been an extraordinary expansion of the toolkits used by central bankers. Policies like quantitative easing, yield curve control, purchases of corporate bonds, forward guidance, and so on, all emerged anew into the monetary policy basket under the leadership and technical expertise of academic scholars and experts like Ben Bernanke and Janet Yellen. These policies have been hailed for rescuing and restoring the economy and financial markets, both during the GFC and after the COVID-19 pandemic.

However, it is now apparent that the long period of monetary accommodation engendered by these policies, under the watch of esteemed experts, has contributed to an addiction to cheap money, perpetuated zombie companies, turbocharged financial models like private equity, and inflated financial market bubbles. It’s a legitimate and very compelling argument that these policies have prevented the small recessions necessary to clean up excesses and realign incentives.

Instead of technocracy binding politicians to the mast and restraining them from the pursuit of excessively loose monetary policy, the expert central bankers appear to have shown the politicians the way with new toolkits to perpetuate cheap money policies. The most egregious expression of this reshaping of expectations is Donald Trump’s demands from the US Federal Reserve.

This fetish with technocracy is not confined to central banking. Based on the successes attributed to technocratic central banking, economists have argued in favour of fiscal councils to independently evaluate and monitor the expenditure and tax policies of governments. They say that fiscal councils, with their independent role, can counter the deficit bias of governments and prevent fiscal dominance. Accordingly, many Western countries have some form of fiscal councils.

In this context, Andrew Haldane, former Chief Economist of the Bank of England and one of the most respected economic commentators, has set the cat among the pigeons by questioning the role played by the UK’s Office of Budget Responsibility (OBR) in the country’s fiscal management. The OBR was established in 2010 to provide an independent assessment of the country’s public finances and thereby depoliticise fiscal policy analysis. It mimics the independent fiscal policy councils operating in some countries, which provide an independent view on the Government’s macroeconomic forecasts and fiscal decisions.

However, the OBR’s role goes beyond mere assessment of fiscal policy to playing the central role in making macroeconomic forecasts and assessing the impact of fiscal measures. It had, as Haldane writes, “monopoly rights over judgments on debt sustainability.” In other words, the Treasury outsourced its role in this to the OBR, including transferring much of its in-house expertise to do this role. This was a pure form of technocracy.

Haldane says this outsourcing to a technical entity has contributed significantly to the UK’s current economic stress by subordinating economic growth to excessive fiscal discipline, with its inevitable political consequences.

Since 2010, fiscal policy has involved delicately balancing measures to stimulate growth with maintaining fiscal discipline. The OBR’s mandate covers only the second. Its scoring of fiscal measures decisively tips the institutional balance towards conservatism over growth. Or rather, it has reinforced the Treasury’s long-standing fiscal-first instincts… After years of under-investment, the UK’s public sector capital stock is estimated to be around £2tn lower than its international counterparts in 2019, a gap almost certainly larger now. Not coincidentally, growth has stalled. An unedifying sequence of gossamer-thin growth plans has been accompanied by mounting political disquiet at OBR conservatism.

This culminated in Liz Truss’s decision to sideline the OBR in preparations for the fateful 2022 “mini” Budget. The resulting bond market meltdown led present chancellor Rachel Reeves to hardwire OBR assessments into fiscal events, making the de facto monopoly de jure. Buyer’s remorse has been rapid. With a weakening outlook and far too little fiscal wriggle room, Reeves finds herself impaled on the OBR’s horns. On its educated guesses — and that inevitably is what they are — now hang the fortunes of the chancellor, the economy and tens of millions of taxpayers… Nigel Farage, whose Reform UK party leads comfortably in opinion polls, suggests that weak growth is the OBR’s fault.

As Haldane writes, the OBR appears to have done its job all too well, only to the extent of squeezing hard on economic growth itself. In this backdrop, Haldane’s suggestion is to limit OBR’s role to auditing the Treasury’s assessments.

One way of freeing the government’s fiscal hands is by partially taking back control of fiscal assessments. Outsourcing your brain is rarely wise. As with the Bank of England for monetary policy, the Treasury should produce and publish its own economic projections and assessments of fiscal choices. The OBR’s role, as in other countries, would then be to audit these assessments. With the Treasury no longer as tightly bound by OBR conservatism, the institutional balance would be tipped towards growth while preserving independent scrutiny. Increasing transparency around fiscal choices improves public debate.

In the context of the debate about the superiority of independent technocratic entities like central banks or fiscal councils, especially given the fiscal bind in the UK, India’s post-pandemic experience is instructive.

The country’s fiscal framework, enshrined in the Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management (FRBM) Act, mandated governments to keep their gross budget deficits under 3% of the GDP, a benchmark that has no objective basis but was straight borrowed from the EU (where, too, it was forced without any objective basis). While it was never strictly followed (except for state governments), it nudged successive central governments not to stray too far from this number.

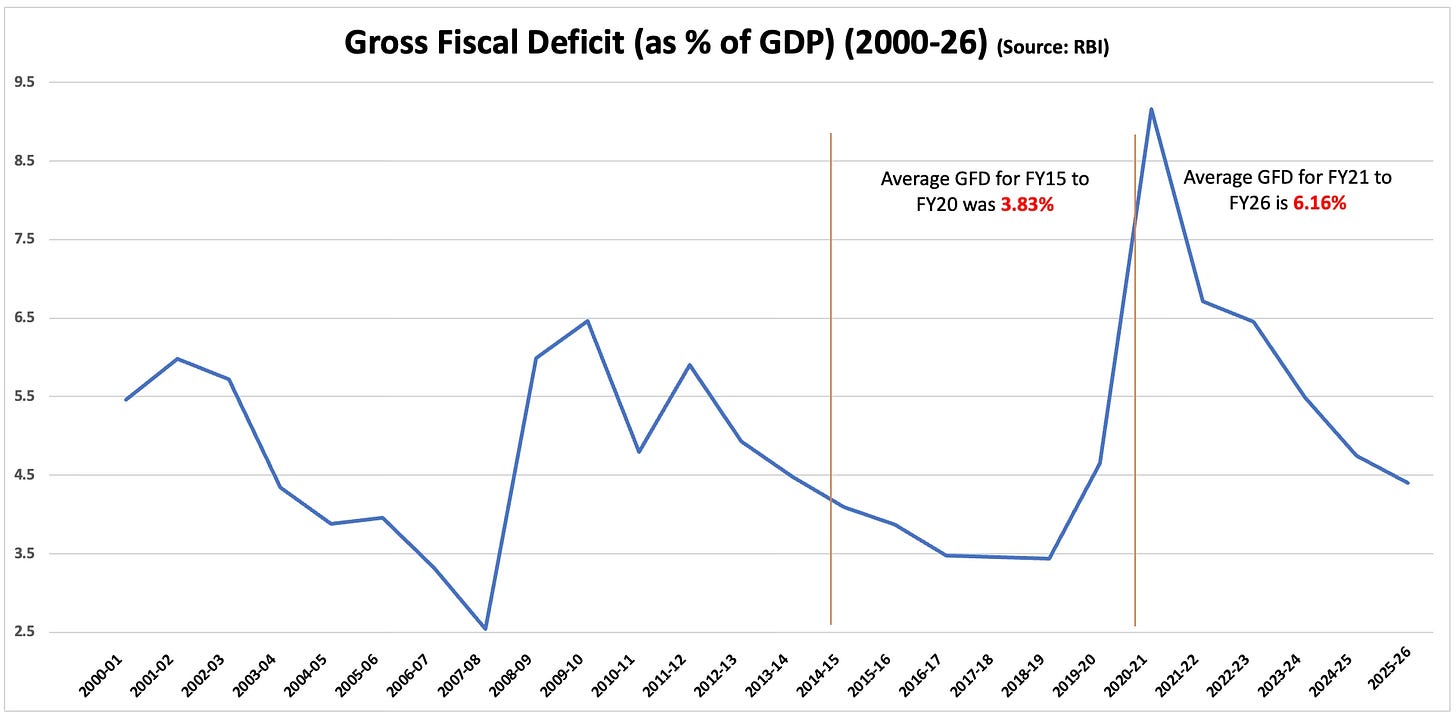

The pandemic helped break away from this constraint and allowed the central government to find an average of nearly 2.5 percentage points of GDP of additional fiscal space (comparing the six years immediately before the pandemic with those immediately after). This additional fiscal space has been critical, almost single-handedly responsible, in sustaining and boosting economic growth. It is to the government’s credit (a surprisingly less acknowledged thing) that it used this additional fiscal space not to dole out subsidies and other revenue expenditures, but on good-quality capital expenditures that created durable assets, and also to clean up its budget books.

The big post-pandemic fiscal deficit and the failure to reverse course quickly to the FRBM benchmark raised criticism from experts and opinion makers. They warned of macroeconomic instability, a surge in public debt, capital flight, growth squeeze, and a knock-on effect on the equity markets. None of these has materialised, and, despite the headwinds from global uncertainties and weaknesses, the Indian economy remains in reasonably good shape.

Inflation has been low and growth high, especially when compared to peers and advanced economies. In fact, while it will be a matter of debate, there may now be a case to even revisit the fiscal framework to anchor the benchmark at about 4% of GDP.

The point here is not to reject technical expertise and technocracy in macroeconomic policymaking and public policy in general, but to caution against excessive reliance on them. Public narratives tend to endow them with expertise and prescience far in excess of what they possess, especially in complex areas like macroeconomic decision-making. Given the deeply political nature of these decisions, it’s more appropriate if they are taken within governments, by drawing on the inputs and expertise of technical experts.

No comments:

Post a Comment