It is a reality of life that narratives that are grounded in stories trump sophisticated theories grounded in logic and reason.

The booming hype cycle on AI is only the latest example. References to AI and ML have become de rigueur in any sales pitch about innovative solutions, regardless of the context. Everything from food delivery to manufacturing in the private sector is being claimed to be dramatically improved with some underlying AI engine. Notwithstanding the lack of any meaningful commercial success, the AI bubble continues to inflate at a rapid pace.

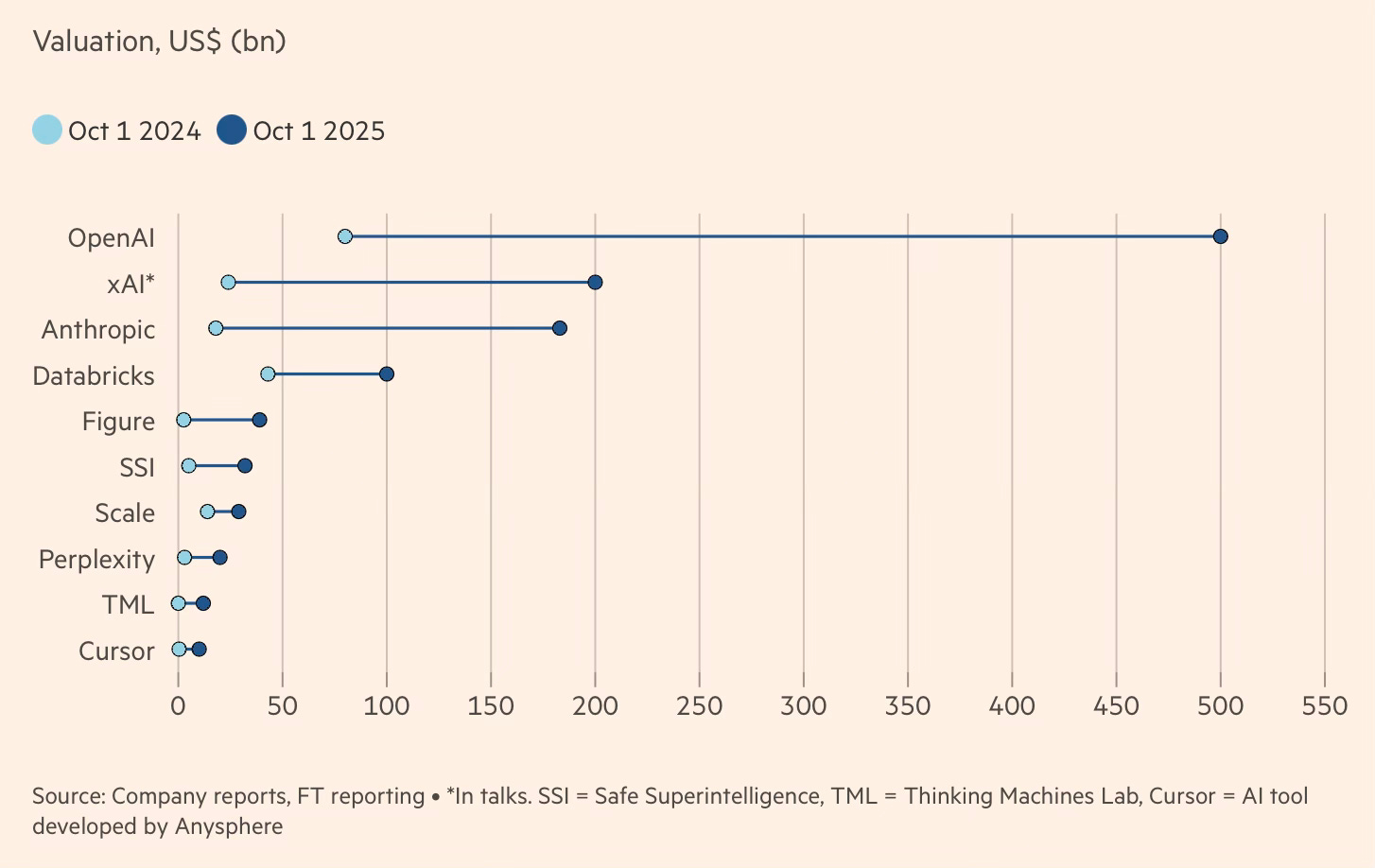

As an illustration, over just the last 12 months, the top ten AI startups, all loss-making, have attracted $161 billion in VC capital (two-thirds of all US VC spend) and gained close to $1 trillion in valuation.

The AI mania is not confined to areas of high technology and finance. Even within the more prosaic environments of public systems, it has become a norm to fit AI/ML into any new public policy idea or program or project for virtue signalling. Never mind its relevance and value, proponents put forth claims of using an AI/ML layer to embellish their ideas. Even simple data analytics solutions that are basically data description, without even basic analysis, are presented as having a layer of AI/ML.

FT’s Gillian Tett points to the practice of “cargo cults” used to describe the phenomenon observed among the native inhabitants of the Melanesian islands that were invaded by Westerners in the 19th century and flooded with previously unseen consumer goods. Dimitris Xygalatas writes

When Indigenous communities throughout the area had their first encounters with colonial forces, they marveled at the material abundance the foreigners brought with them. During World War II, when many Melanesians worked for U.S. and Australian military forces, they observed soldiers who never seemed to engage in any productive activities, such as fishing, hunting, working the land, or crafting anything. All they did was march up and down, raise flags, chant anthems, and signal toward the sky. And when they did that, metal birds appeared and dropped all kinds of goods for them. The Indigenous observers concluded that the strange rituals were causing the cargo to arrive.

With the end of the war, the military bases were abandoned and the goods ceased to arrive. To get the cargo to return, local chiefs began organizing ceremonies that mimicked the rituals of the troops. Soon, elaborate myths and theologies developed around those rituals. Surely, the cargo must have been a gift from the gods—their own ancestors. After all, who else could be capable of producing such wealth? The foreigners had merely discovered the rituals that unlocked these treasures…

But the only airplane present is a full-size wooden replica of a light aircraft. On one side of the strip lies a control tower made of bamboo. On the other sits a satellite dish built of mud and straw. Undeterred by the apparent lack of any actual aviation technology, some of the men light torches and place them alongside the runway. Others use flags to wave landing signals. Everyone raises their gaze to the sky in anticipation.

Tett extends the cargo-cult phenomenon to the current AI mania.

Physicist Richard Feynman borrowed this metaphor to decry “cargo cult science”, cases where researchers “follow all the apparent precepts and forms of scientific investigation, but they’re missing something essential, because the planes don’t land”. The same analogy now applies to AI. Almost every business executive today is eager to tell investors about their AI strategy (even though 95 per cent of companies have not (yet) seen revenue gains) and every VC group is keen to show AI plays. Similarly every Big Tech executive is investing in massive data centres, even though Bain reckons some $2tn of revenue will be needed to fund this by 2030. And charismatic figures like Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, keep promising fresh magic. Or as Stephan Eberle, a software engineer, laments: “Watching the industry’s behaviour around AI, I can’t shake this feeling that we’re all building bamboo aeroplanes [like cargo cults] and expecting them to fly.”

In the case of investors, the cargo-cult phenomenon works through fear of missing out (FOMO).

The iconic example of our times of the narrative transcending all logic is how Tesla’s equity market valuation has become tied to the Elon Musk phenomenon. In substantive terms, Tesla has been falling behind in all its major markets and may now be technologically behind its Chinese competitor, BYD. The latter has a superior battery technology, is vertically integrated, and has not only caught up on automatic driver assistance systems (ADAS) but may even have pulled ahead.

With more than 95% of its global deliveries coming from Model 3 and Model Y, and that too for nearly a decade, Tesla is now a two-trick pony. In contrast, BYD has a dozen models globally and is releasing new models each year. Tesla’s growth has been primarily driven by lowering the prices of its existing models, hoping to offset margin declines with volumes. Its gross margin, excluding regulatory credits, has declined sharply from nearly 30% in the fourth quarter of 2021 to around 17% in the second quarter of 2025.

But in an inversion of all logic, this decline has been accompanied by an increase in its market valuation to $1.4 trillion, more than ten times that of BYD. Such valuations are built on the premises of high margins, and runaway hits like robotaxis and AI-powered robots. These premises are, in turn, built on the narrative of the cult of Elon Musk and the miraculous powers endowed on him. Tesla is one mega-giant bet on Musk, perhaps the biggest financial market bet on one individual in history, by some distance.

In each of these cases, once the irrationality has taken hold thanks to the narratives, it tends to find rational explanations. A commonly cited one is that such bubbles may have become the only way to mobilise resources at the scale required to push the technology frontiers. Sample this.

“There will be casualties. Just like there always will be, just like there always is in the tech industry,” said Marc Benioff, co-founder and chief executive of Salesforce, which has invested heavily in AI. He estimates $1tn of investment on AI might be wasted, but that the technology will ultimately yield 10 times that in new value. “The only way we know how to build great technology is to throw as much against the wall as possible, see what sticks, and then focus on the winners,” he added.

This explanation also syncs with the dominant VC model of financial intermediation and allows them, in turn, to raise the massive amounts of capital required to fund the bubble.

In the case of the AI bubble, there’s also a powerful strategic imperative. As Gillian Tett has pointed out, given the threat to America’s technological superiority posed by China’s state capitalism, such bubbles may well be “the only way American capitalism can ever amass the scale of investment needed to create this type of ambitious infrastructure”.

While it may sound heretical, the AI bubble also highlights the unique nature of American capitalism, which has shown an unmatched appetite to assume excessive risk in the expectation of windfall returns. It is only the latest, albeit far bigger, in the line of irrational exuberance and risk assumption that has distinguished the US economy even in the last five years - WeWork, GameStop, NFTs, cryptocurrency assets, SPACs, etc. As Andrew Ross Sorkin has pointed out, “there is no innovation without speculation” and “speculation built America”. So he writes,

“Speculation isn’t a bug in America’s economic code, but a crucial component part of the engine… Speculation is often caricatured as gambling. But at its core, it is belief plus risk. It is the act of investing capital in a highly uncertain outcome, hoping for reward.”

In Tesla’s case, too, the irrationality gets justified in terms of Musk’s superhuman talent. This is nicely captured in Tesla’s battles with courts and shareholders to get approval for Musk’s astronomical $1 trillion pay package.

Tesla management has sold it in terms of binding Musk to remain sufficiently committed to the company, amidst his other multiple business interests. In fact, Board Chair, Robyn Denholm, has justified it, calling Musk a generational talent who would have to expend “time, energy, and effort beyond what most humans can do.” She said, ‘There’s just not anybody, either inside or outside the organisation, that is Elon today.” In what is effectively a blackmail/bluff, Musk himself has said he’ll leave Tesla if he does not get the pay package and gain greater control over the company to protect it from hostile takeovers that can detract from its efforts to develop AI technology and humanoid robots.

The Musk compensation issue would be unimaginable in any other country. In the US, as Denholm suggests, astronomical compensation packages have become part of an entrenched narrative that those CEOs deserve these amounts. There’s no logic, both in terms of substance (the expertise brought in by the CEO) or market demand (the scarcity of such executives), that can justify even remotely close to these amounts. Numerous studies have consistently shown no correlation between executive compensation and shareholder returns.

Instead, the phenomenon of such excessive CEO pay is fuelled by narratives (and the market structures and incentives) that have become part of the US corporate culture. Narratives shape cultures.

In this context, it is important to remember that the central role of narratives in shaping the biggest mainstream economic trends is a big gap in economic thinking. These narratives, which stand in complete opposition to orthodoxy and logic, must be an essential component of any college or university economics curriculum.

To some extent, the mainstream economists have grudgingly accommodated parts of it in the guise of behavioural economics and finance. In this reading, while rational economic agents continue to dominate the economic decision-making, human cognitive failures and idiosyncrasies result in some occasional deviations.

Given how pervasive these deviations are in the real world, this reading must be revised to provide a more central role for narratives that deviate sharply from logic and orthodoxy. Economic decisions, both in corporations and by governments, are also cultural and political choices, and these preferences often dominate. While those choices are grounded in logic and orthodoxy, other considerations also inform them. These considerations are shaped by the specific narratives surrounding them.

Interestingly, many economic orthodoxies themselves have become narratives sans any empirical basis. I have blogged here about 25 such orthodoxies that dominate the discourse without any empirical basis.

No comments:

Post a Comment