Amidst all the concerns about China’s weaponisation of its manufacturing dominance, we tend to overlook the critical role played by Western multinational corporations in helping China develop those capabilities.

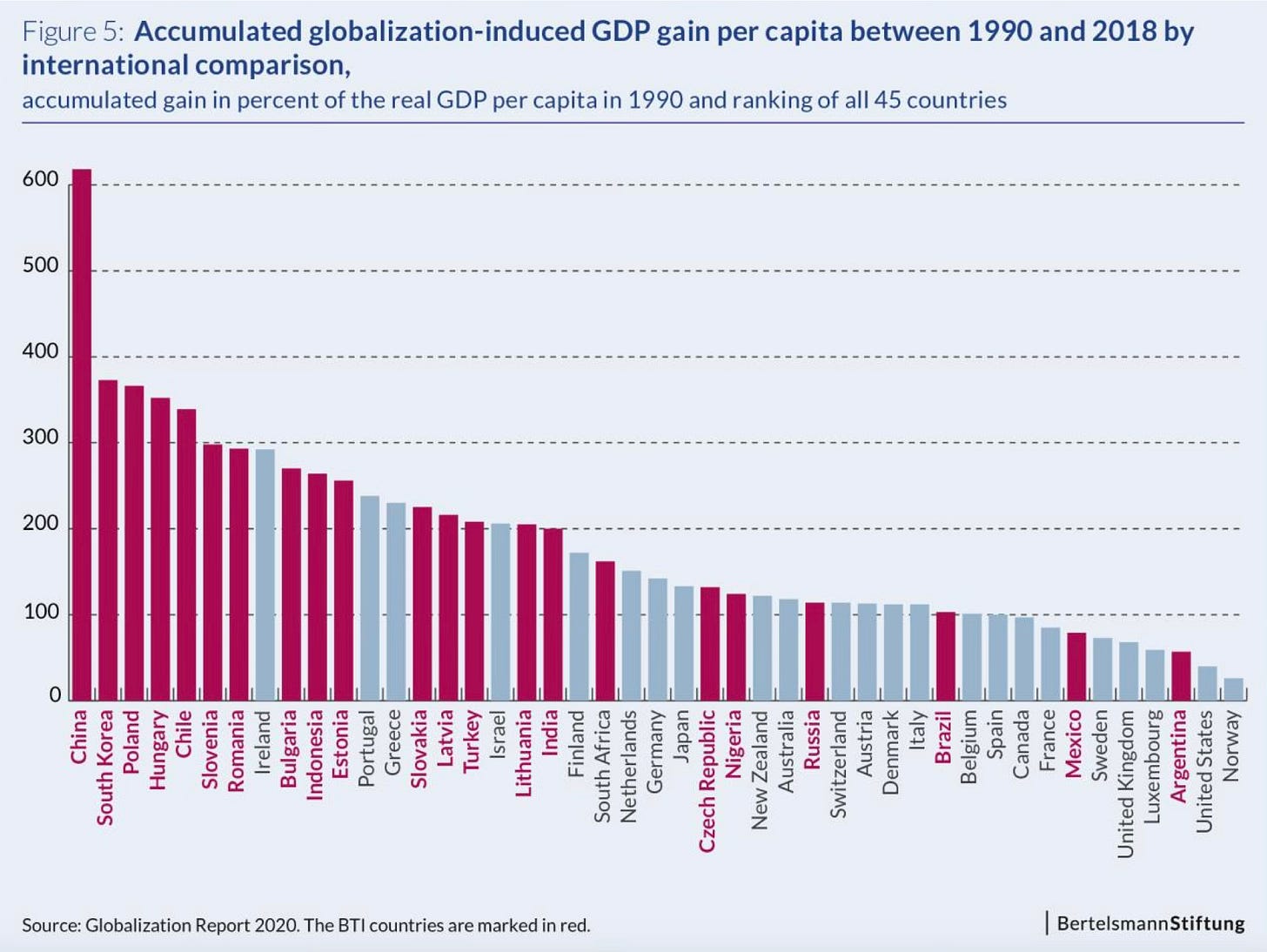

I had blogged earlier about how Apple and the iPhone made China. As this Bertelsmann Institute report shows, China has been the standout beneficiary of the era of globalisation spanning the last three decades.

In this backdrop and as US companies shift their operations away from China, a new paper by Jaedo Choi, George Cui, Younghun Shim, and Yongseok Shin reveals how joint ventures by US companies in China have strengthened Chinese firms, reduced US welfare, and benefited large US firms at the expense of small firms and the real wages of workers.

They show that, notwithstanding the risks of technology leakages, the US companies, by and large, voluntarily complied with the Chinese policy that explicitly or implicitly mandated technology transfer by MNCs through JVs. This ultimately led to over-investment in the JVs and excessive technology transfer to China, resulting in profit losses for other US firms due to intensified competition from China.

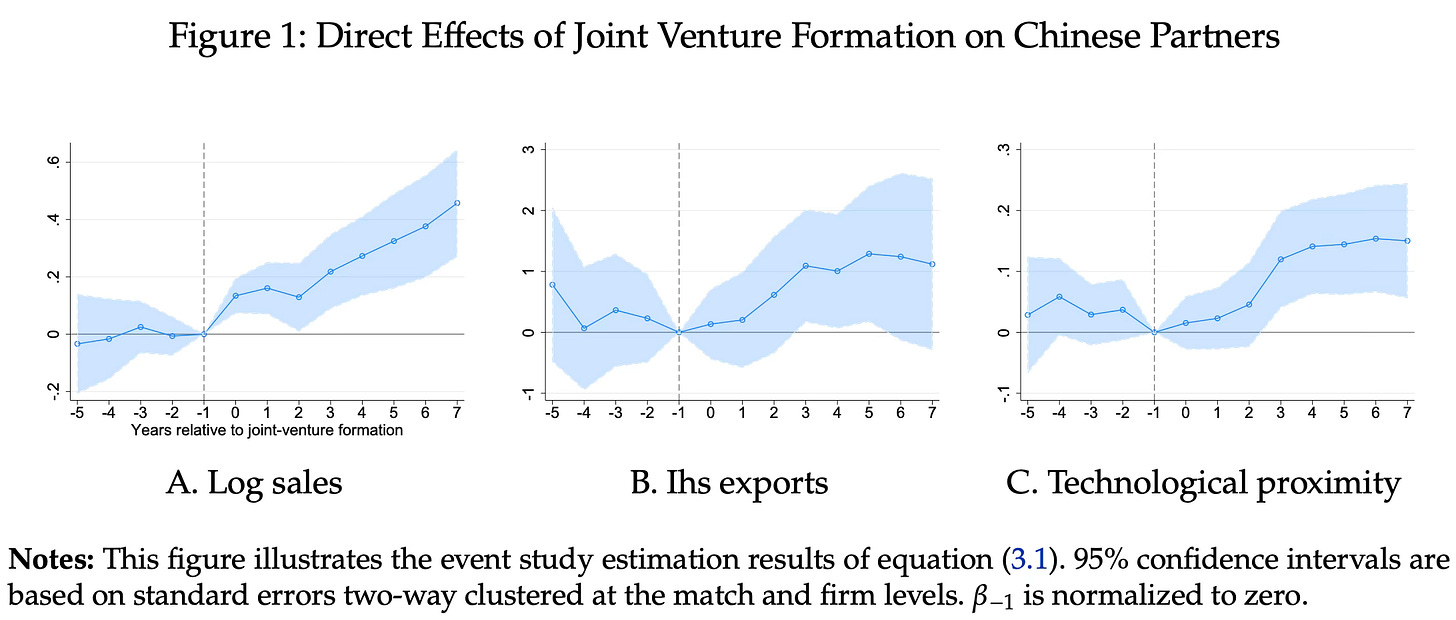

One novel finding is that US firms experienced more negative outcomes in industries with more joint ventures in China… Our quantitative analysis shows that there are indeed too many joint ventures in equilibrium relative to the social optimum for the US… we find direct positive spillovers from MNEs to Chinese parent firms (or partners) of joint ventures… Following the formation of joint ventures, Chinese parent firms experienced significant growth in sales, capital, and exports. Furthermore, their patenting activities became more similar to those of their MNE partners, indicating a direct diffusion of technology between partners through joint ventures… we find evidence of indirect spillovers to other Chinese firms. In industries with more FDIs (joint ventures and wholly foreign-owned enterprises), even the Chinese firms that were not a party to a joint venture grew faster and more technologically advanced… we find that in industries with more FDIs into China, US firms experienced more negative outcomes in terms of sales, employment, investment and innovation.

They use a two-country growth model to estimate the impact of such joint ventures.

Once a joint venture is established in China, the probability of technology diffusion from the US leader firm to the Chinese leader firm increases, consistent with our empirical finding of direct spillovers. As a result, the surplus from a joint venture includes not only the flow profit of the joint venture firm but also the value of the higher probability of technology diffusion to the Chinese leader firm. Additionally, Chinese fringe firms, which do not participate in any joint venture by construction, benefit indirectly. This is because there is an additional source of technology diffusion—the joint venture firm itself—within the industry, and the Chinese leader firm is likely to have higher productivity after forming the joint venture…

The entry of a new joint venture firm immediately intensifies competition in the industry. The stochastic technology diffusion to the Chinese leader and the fringe firm further intensifies competition over time. The US leader takes all these competition effects into account when making the joint venture decision. It also partially captures the profit flow of the joint venture and the spillover benefits to the Chinese leader through bargaining. However, it ignores the negative effects of heightened competition on the profits of its domestic competitor, the US fringe firm…

US leaders benefit from joint ventures in the short run through lower trade costs for serving the Chinese market and lower wages in China. They also partly capture the value of technology transfer to Chinese leader firms through bargaining. Over time, however, Chinese firms catch up faster due to the technology diffusion facilitated by these joint ventures, and the heightened competition negatively affects US leaders. Nevertheless, the present discounted value of US leaders’ profits is higher with joint ventures—otherwise, they would not invest in them. For US fringe firms, leader firms’ joint ventures have only a negative effect on their profits, through intensified competition from China. Because US leader firms ignore this negative effect on US fringe firms, there may be too many joint ventures relative to the US social optimum.

They point to important impacts of JVs on innovation and comparative advantage.

On the one hand, the increased probability of technology diffusion to China means that profits from successful innovations are smaller and shorter-lived, which may reduce innovation efforts. On the other hand, the option to form a joint venture makes US leaders innovate more, because their innovation increases profits from the joint ventures and the fees they receive from Chinese leaders through bargaining. In our quantitative analysis, the former dominates in the medium to long run, so US leaders innovate less with joint ventures. For Chinese leaders, technology diffusion serves as a substitute for their own innovation efforts, and they innovate less with joint ventures.

Furthermore, in the model, the value and hence the likelihood of forming joint ventures for US leaders are higher when the US-China technology gap is larger, which we confirm in the data. Since joint ventures reduce the technology gap between the US and Chinese firms through technology diffusion, they have the effect of eroding the US comparative advantage and terms of trade, reducing the gains from trade for the US.

The authors use their model to calculate the short and medium-term impacts of a ban on JVs from 1999.

We find that prohibiting joint ventures increases US welfare by 1.2 percent in units of permanent consumption. For the US, leaders’ profits fall by 22 percent in present value terms, while fringe firms’ profits increase by 4.9 percent. The total profit of the corporate sector declines. Yet, the real wage increases by 2.9 percent due to higher labor demand in the US, leading to the overall welfare gain. The ban has a transitory negative effect, because US firms cannot immediately benefit from lower wages in China and reduced trade costs via joint ventures. However, this effect is outweighed by medium-run benefits, as the US maintains its technological advantage over China for longer, driven by higher innovation efforts and less technology leakage to China.

As for China, when the US bans joint ventures, Chinese leader firms compensate for reduced technology diffusion by increasing their own innovation efforts. However, China’s productivity growth is substantially delayed, and the absence of joint ventures reduces China’s welfare by 10.3 percent in units of permanent consumption. In China, the profits of both leaders and fringe firms, as well as the real wage, are lower without joint ventures from the US.

The role of the JV model of technology transfer is an under-appreciated aspect of China’s economic growth. More the technology gap, the greater the economic benefits to the host country for the investment through the JV strategy.

A JV mode of technology transfer, especially in the scale and manner that China has achieved (the iPhone is the best illustration), is not replicable. No other country has the political system and economic advantages that enable its firms to undertake the kind of hard bargaining required to extract JVs that involve technology transfer. There are at least two aspects.

Only an authoritarian one-party system like China can summon the level of coordination and discipline required to force such JVs on foreign multinational corporations. Complementing this, the Chinese firms, too, (with the guidance of the Government) have shown an unmatchable level of commitment and enterprise to use the JV as a springboard to vault them into global leadership in their industry. It’s this combination of the two, government and private sector, working together, that made these JVs succeed in technology transfers and quickly move Chinese firms up the value chain. This is Public Private Partnership (PPP) with Chinese characteristics.

On the face of such evidence, it is not tenable for the US (and European) firms to continue with such JVs even as China tightens its dominance in manufacturing and the Cold War intensifies. The restrictions imposed by the US on multinational corporations’ activities in China in strategically important sectors must be viewed in this context. This should also be another reminder to all remaining supporters of continuing normal trade and investment activity with China (academic scholars who promote free trade, and corporate interests intent on maximising their private gains from such trade).

The normal rules of the game on the economy and trade do not apply when faced with a political and economic system like that in China. Even those arguing that China will gradually vacate the lower-value-added manufacturing and move up the value chain are most likely wrong, since, given the continental size and diversity (in terms of stages of development) of the economy and its unparalleled competitive advantages, China is unlikely to vacate them in any meaningful manner for a long time.

The other takeaway from this is that while it may not be possible for other countries to emulate China’s approach to JVs with foreign companies in full, it’s useful to make them an important instrument of their industrial policies. No country is closer to China in this respect than India. It has many of the economic advantages that China offers to foreign MNCs, which make it acceptable enough to agree to such JVs.

In areas like defence equipment, aeroplanes, renewable energy generation, metro railways, smart meters, telecom equipment, surveillance cameras, and so on, the Indian market is among the largest for foreign firms. It provides the government sufficient bargaining power to single-mindedly pursue the objective of maximising technology transfers through JVs. It should show the coordination, discipline, and persistent pursuit required to achieve the objectives.

No comments:

Post a Comment