A feature of the housing markets is that they are rife with market failures. Specifically, as I had blogged earlier on multiple occasions, left to itself, the market will not be able to meet the affordable housing demand.

In this context, one influential argument is that increasing the supply of housing stock of any kind will invariably translate to reducing affordable housing prices. Supply trickles down market segments and puts downward pressure across them. I’m not sure.

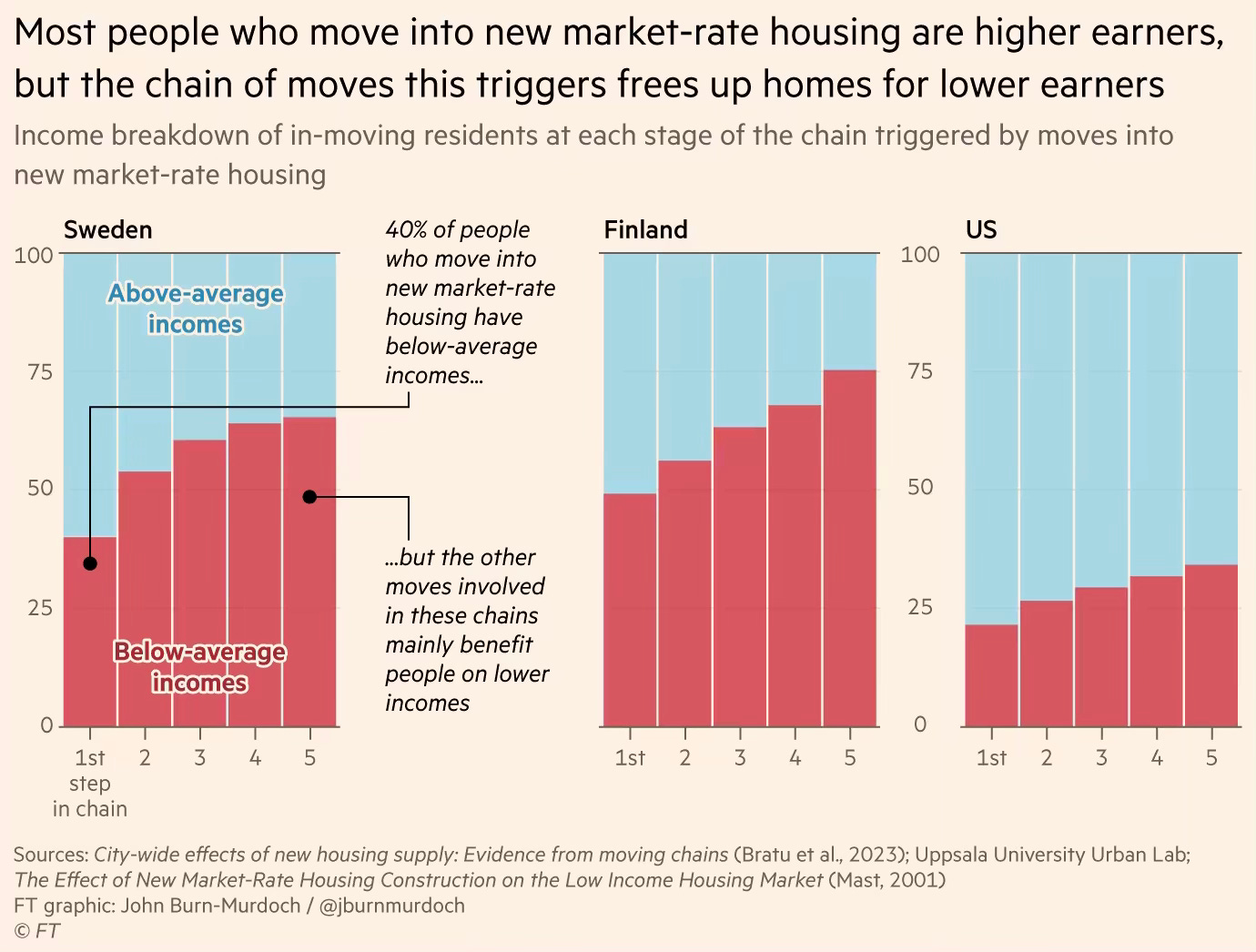

John Burn-Murdoch points to two important features of the housing market and writes that increased housing supply of any kind generally contributes to containing the rise of affordable housing prices.

The first is about the cascading effect of the supply of market-rate housing on the affordable housing market.

Market-rate dwellings will simply go to people on higher incomes, leaving lower earners high and dry. But recent studies from the US, Sweden and Finland all demonstrate that although most people who move directly into new unsubsidised housing may come from the top half of earners, the chain of moves triggered by their purchase frees up housing in the same cities for people on lower incomes. The US study found that building 100 new market-rate dwellings ultimately leads to up to 70 people moving out of below-median income neighbourhoods, and up to 40 moving out of the poorest fifth. Those numbers don’t budge even if the new housing is priced towards the top end of the market.

The second is that gentrification does not generate the disturbing displacement of lower-income residents from the areas they have lived and worked for long.

Another argument is that building market-rate housing in a lower-income area leads to gentrification, with higher earners moving into a lower-income area and displacing the incumbents. But the latest research from Britain and the US shows that there is typically little, if any, outward displacement of incumbents. It is the incomers who have been displaced, priced out of wealthier areas by supply constraints. In other words, even if you think it’s inherently bad if high earners move into poorer neighbourhoods, the answer is to build more market-rate housing for those higher earners.

In this context, the example of Milan is instructive. There have been stories across news outlets in recent days about Milan’s real estate boom and the corruption scandal that has broken out involving local officials, politicians, and real estate developers. It involved developers bribing local officials and politicians to fast-track permissions in violation of the city’s planning regulations and obtain illegal building permits.

Over the last decade, there has been a spectacular surge in the demand for high-end residential property, which has been reinforced by tax concessions.

In 2015 Milan hosted the Universal Exposition, seizing the chance to demonstrate that the once provincial and austere financial capital of Italy was morphing into a vibrant global city, thanks in large part to the 340,000-square-metre urban regeneration plan. Since the Expo… the city’s property market has attracted €30bn in investment and thousands of wealthy international residents, lured to Italy by generous tax breaks. Since 2016 Italy has offered new residents a flat-tax charge on unlimited overseas income, a fee that rose from an annual €100,000 to €200,000 last year. The country has enticed wealthy expats who deserted the UK after its Labour government last year scrapped the popular “non-dom” regime, which offered residents whose permanent home was abroad up to 15 years without paying tax on money held overseas.

The result of the supply boom has been gentrification, with large parts of the city itself being gentrified.

Two decades ago the drab suburban district north-east of central Milan — once characterised by railway yards and factories making Pirelli tyres and Breda steel — was so desolate and plagued with crime that regular Milanese would never think to visit. Today it is the city’s most exclusive neighbourhood, home to global bankers and billionaires. Its curved and gleaming UniCredit tower was designed by the late architect César Pelli, renowned for Kuala Lumpur’s Petronas towers. Nearby is the Bosco Verticale, a pair of skyscrapers where apartments sell for up to €25mn to private equity executives, footballers and Middle Eastern investors. The glitzy Porta Nuova district was masterminded in large part by one man: Manfredi Catella, who led the Italian arm of US property asset manager Hines, then acquired the former Hines division through his family’s real estate vehicle Coima in 2015, building up the district with backing from Qatar’s sovereign wealth fund…

Complaints about the multiple high-rise developments that sprang up, mainly in working-class districts, triggered a series of investigations into alleged fast-tracking of building permits and bending of the rules by local authorities. Since the beginning of last year more than 100 building sites, in which several Italian and foreign developers had invested close to a cumulative €12bn, were seized by authorities, stalling construction. Most of the seized developments had been sold off-plan, leaving 13,500 would-be homeowners in limbo.

However, the supply boom has not triggered the type of cascade that the studies cited by Burn-Murdoch highlight, and instead has spawned a housing affordability crisis.

The boom… made housing less affordable for average Milanese families. Residential real estate prices in Milan have risen by 50 per cent since 2016, reaching an average of €5,500 per square metre, 2.5 times the national average, even as real wages declined. The rising costs have drawn criticism from right-wing and populist parties who have accused the mayor, a popular figure among Milan’s elite, of favouring “real estate speculators” and foreign investors over average households.

See also this

The number of foreigners who made Milan their home after a flat tax on foreign earnings was approved in 2017 are in the thousands, but their ranks are set to increase this year after the UK scrapped its so-called non-dom regime that exempted tax on foreign earnings. For a city of only 1.4 million inhabitants, with a dearth of high-end properties on the market, this influx of affluent foreigners — and Italians returning from abroad, also attracted by a favorable tax treatment — has sent valuations soaring, pricing out locals… The average price to purchase a residential property in Milan was €5,532 per square meter at the end of June, a 52.5% increase since 2016, according to data from Immobiliare.it, a real estate online platform. In Rome, prices rose 3.4% to €3,607 in the same period, the data show.

In general, I’m inclined to believe in trends similar to those in Milan in developing countries like India. The main reason is that the pent-up demand for higher-end housing, both for living and as speculative investment, is much greater in Indian cities. This means that the incremental supply will only go on to keep meeting the pent-up demand and will struggle to trickle down to the affordable housing market.

Another reason is that the gap between market housing and affordable housing is so wide that they get segregated into distinct geographical locations, with the latter relegated to the suburbs. Gentrification further accentuates this segregation. Besides, private housing developers find the margins of affordable housing so low as to be unattractive as a commercial proposition. In any case, from the developer’s perspective, the demand for market-rate housing is so high that it’s foolish to overlook it and venture into affordable housing.

The Business Standard has a good article that shows why market dynamics are unlikely to be able to provide an adequate supply of affordable housing in India.

While demand for sub ₹50-lakh affordable housing prevails, market players cite increased land rates, escalated construction costs and low margins as key prohibiting factors. Some like Mahindra Lifespaces are moving out of the segment, while others are reducing their share of the housing portfolio dedicated to affordable housing… Developers are, however, keen on luxury housing supply where higher costs are mitigated by higher end-user charges and hence better margins, on the Ebitda level. Compared to 10-15 per cent margins in affordable housing - which can easily erode if projects get delayed - high-end residential projects offer Ebitda margins of 25-30 per cent, said industry insiders.

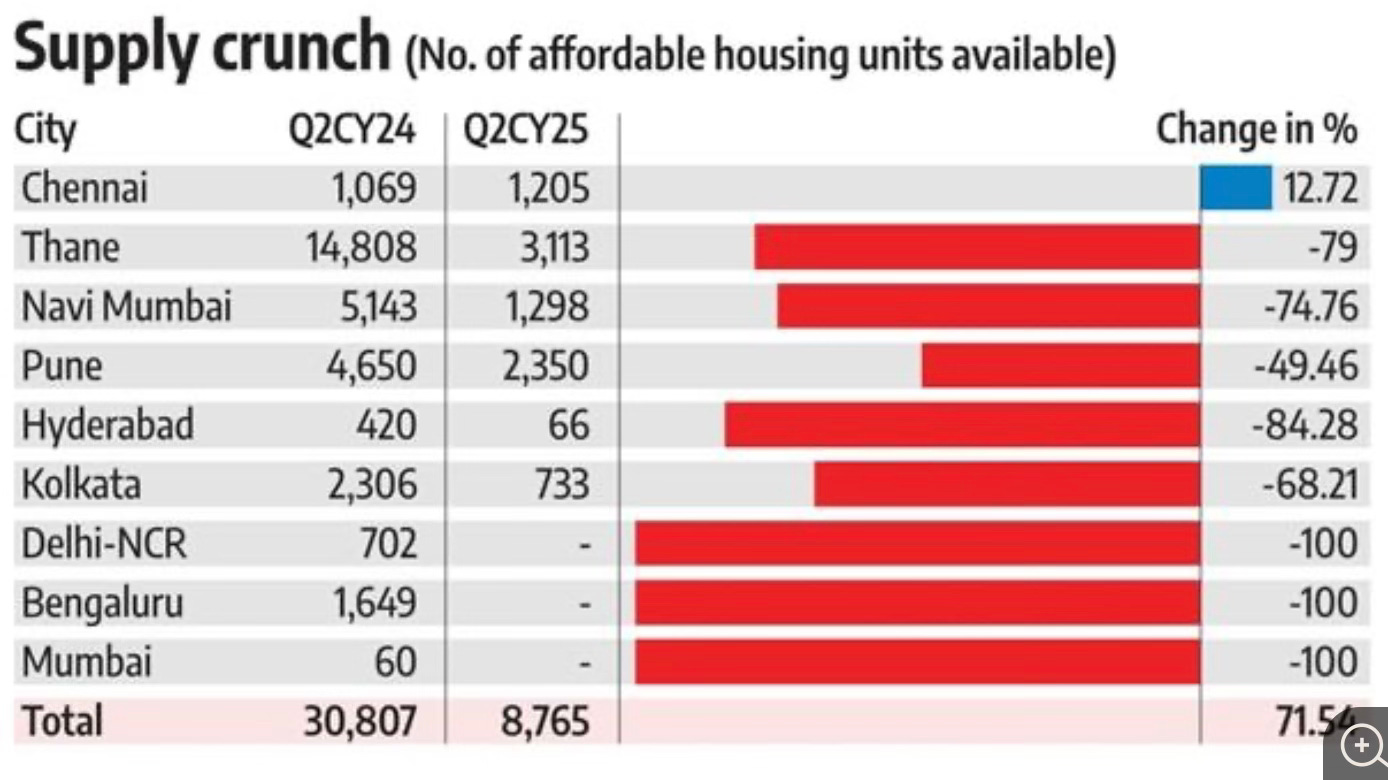

Recently, Mumbai-based Mahindra Lifespace Developers announced its exit from the affordable housing segment by FY28-29… Gurugram-based Signature Global, which started with affordable housing, pivoted to mid-income stock premium housing — ranging between ₹2 crore and ₹4 crore — in the last couple of years, due to rising land prices… According to PropEquity, a listed real estate data analytics firm, in Q2 CY25, there was no affordable housing supply in cities like Mumbai, Delhi NCR, and Bengaluru compared to Q2 CY24. In cities like Navi Mumbai, Thane, Hyderabad, and Kolkata, the supply declined significantly. The affordable supply across the top cities declined by 71.54 per cent year-on-year (Y-o-Y) in Q2 CY25.

“The surge in land acquisition costs, inflated ready reckoner rates resulting in higher stamp duty and registration charges, and steep development premiums make affordable housing financially unfeasible in urban cores. Over 50 per cent of a project’s cost structure is absorbed by direct and indirect taxes, including GST,” Hiranandani added. According to Crisil Intelligence, only 18 per cent of the upcoming residential supply across the top seven cities is estimated to fall in the affordable segment, compared to 45 per cent in the luxury segment… The developers believe that the affordable supply may come, but from smaller developers and in the outskirts of top metropolitan cities… Additionally, the industry experts believe that government intervention is needed in terms of fast-track approvals, land subsidies, credit support, tax benefits, etc., to boost the affordable supply.

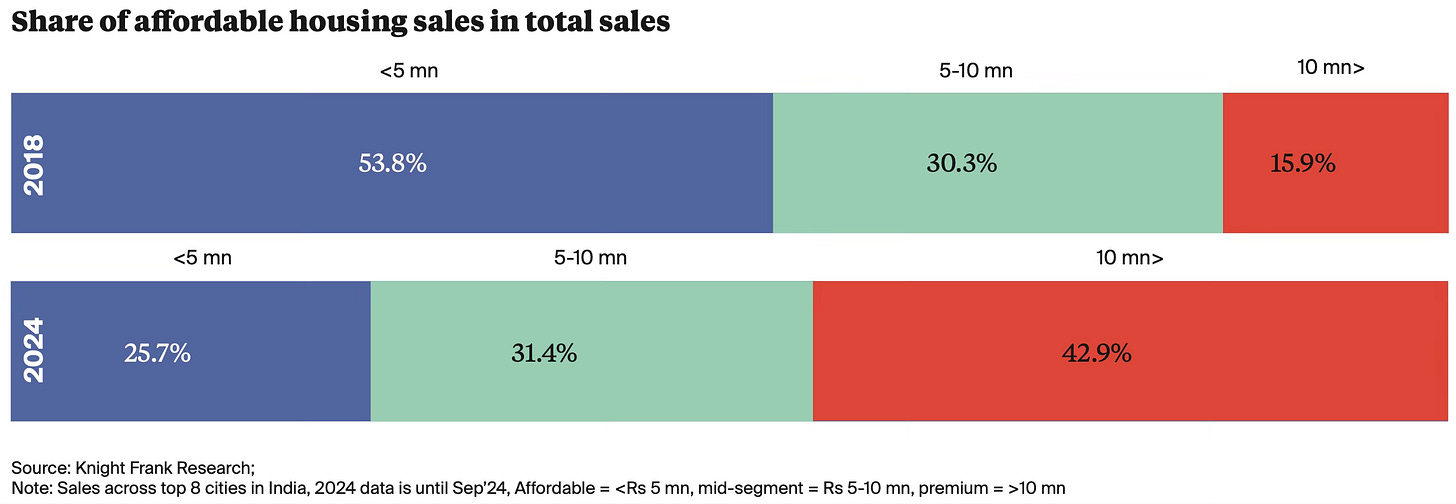

A Knight Frank report finds a sharply declining share of affordable housing in the total housing supply in India, even with affordable housing units defined as those up to Rs 5 million.

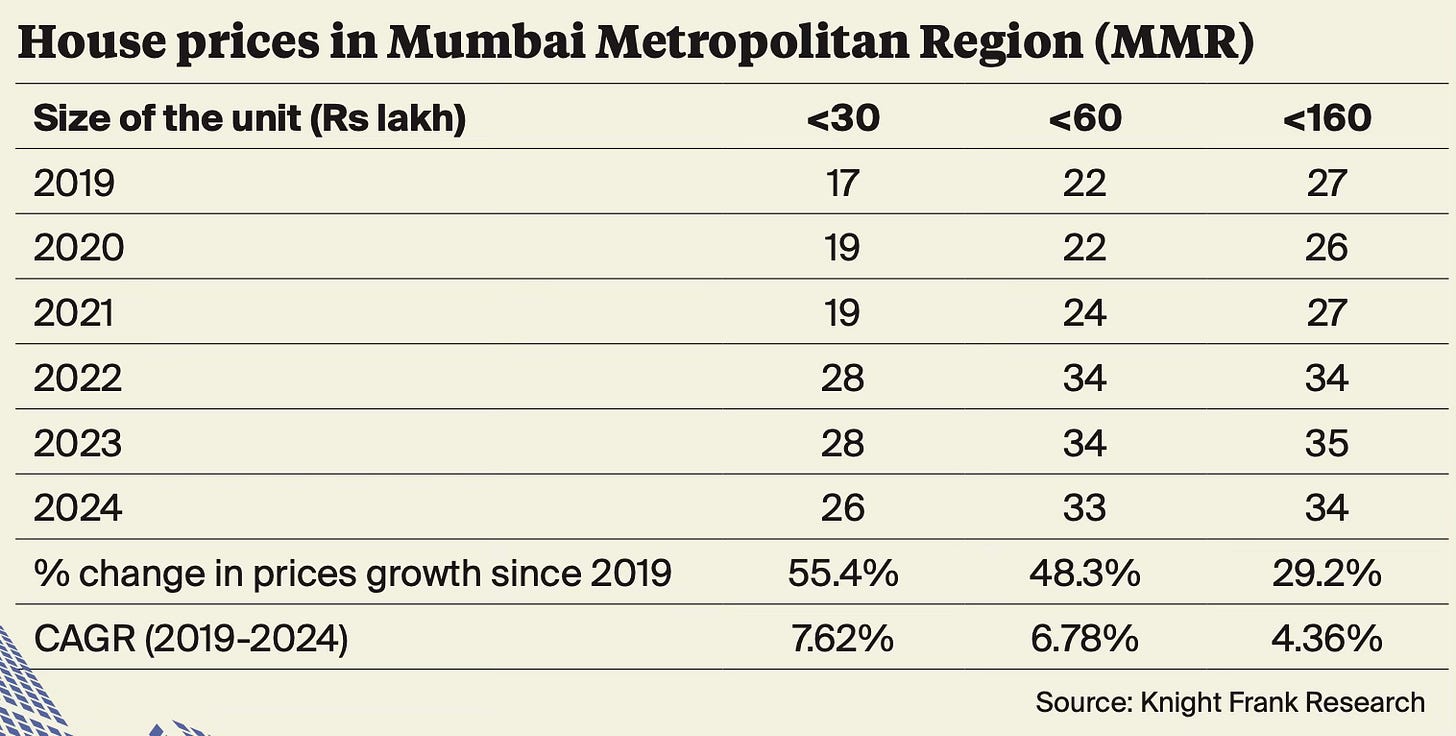

Further, the same report also shows that housing prices have risen much faster in the affordable income segment compared to the highest tiers. While this is for MMR, the situation is unlikely to be any different elsewhere.

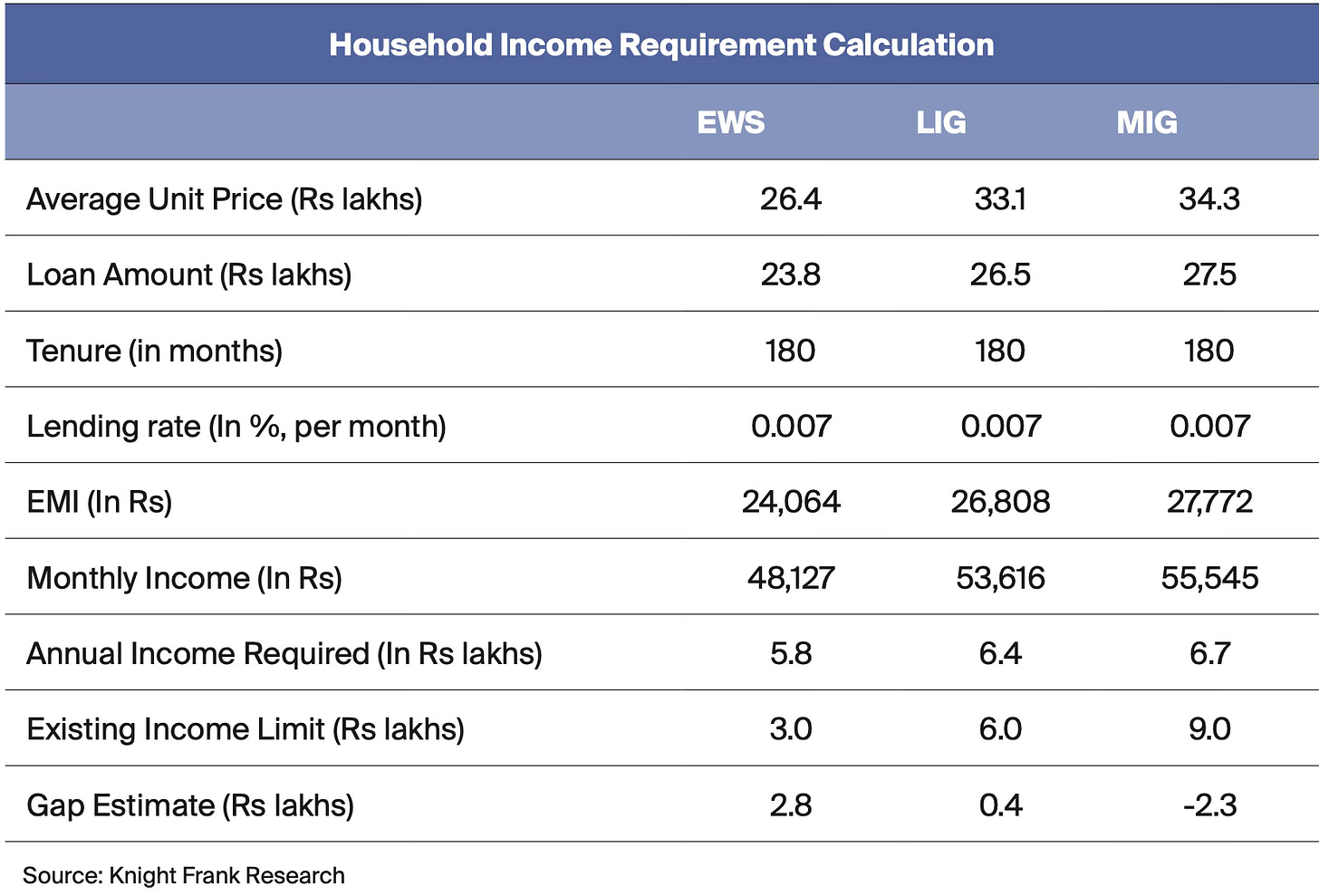

It also shows points to a significant affordability gap in the MMR, even with lower unit costs. If the unit cost is Rs 5 million, the gap will become unbridgeable.

In this context, another article points to how policy changes have contributed to cooling down London’s luxury property market.

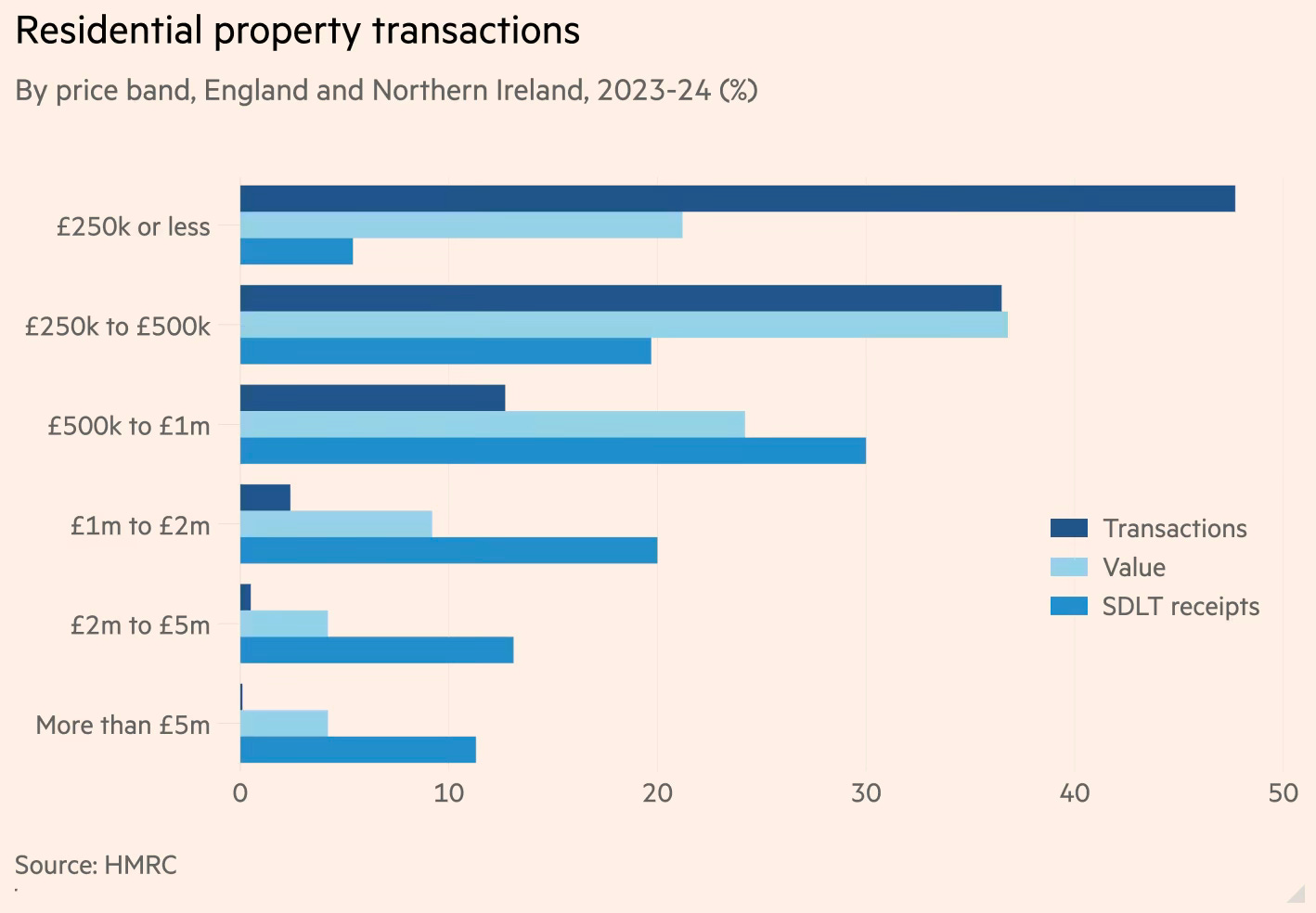

Switching from the “slab” system (where a single rate is paid on the whole purchase price) to a “slice” (where successive bands of the purchase price are taxed at increasing rates) in 2014 may have lowered stamp duty costs for the majority of buyers. But for the sale of multimillion pound properties — which naturally are concentrated in a few postcodes in central London — it increased the stamp duty payable, from 7 to 10.3 per cent of the purchase price for a £10mn home… in 2016… George Osborne introduced the higher rate of additional duty on second and investment homes.

It also shows that while homes priced at £5mn or more might only make up 0.1 per cent of total residential transactions across the country, they account for a far higher proportion of the value of properties transacted (4.2 per cent) and also make up a chunk of the stamp duty collected (11.3 per cent).

This has relevance for India. Housing in India, including the affordable variety, is subject to several taxes and fees - GST of 1-5%, stamp duty ranging from 5-10%, land development charges of 2-5%, premiums and building approval fees of 3-6%, and other municipal fees of 1-2%. In addition, there is the individual/corporate income tax paid by the builders. Currently, affordable housing gets preferential treatment only with a GST of 1%.

Given the experience of the UK, there may be a case for differential application of these duties and fees for affordable housing here, too, to lower its cost. It could be kept very low to limit the fees and taxes on affordable housing to no more than 5-6%. This concession can be restricted to housing below a certain carpet area and value. Property taxes in India, which are extremely low, could also be increased significantly for larger housing units to offset net revenue loss, if any.

The lack or limited impact of housing supply on affordability raises important questions about the housing market itself. If high-end housing supply does not necessarily trickle down the market, and can cause gentrification and also widen the affordability gap, it poses a serious public policy challenge.

It highlights an important aspect of housing. It should not be seen as a typical market-traded good. A home is a vital necessity, and shelter is a fundamental human right. The residential real estate market must first serve its primary purpose of providing housing for all, and only then should it serve investment purposes. If market dynamics have driven property prices sky high, pricing out the middle class and those below, then it’s a market failure that must be corrected through public policy.

While it may today sound retrograde, even stupid, I think that we may not be too far from regulating the housing market to achieve its primary objective. This is especially likely in developing countries, where property markets in the larger cities are already unaffordable to all but the upper-income class. This could involve imposing significant costs and restrictions on very large and opulent housing, and penalising the use of housing as a pure investment (in terms of owning multiple houses) with higher taxes and duties. The differential rates, as in the UK for stamp duty, could be useful strategy in this regard.

No comments:

Post a Comment