There are two distinct stages to manufacturing: product assembly and localisation of components. Industrial policy measures tend to focus on product manufacturing. But countries generally start at the lower part of the manufacturing Smile Curve, with low-value-added activities like mounting components on the PCB (SMT), product assembly, testing, marking, and packaging (ATMP). Domestic value addition comes only with component manufacturing. Then countries move slowly up the value chain with research and development, product design, and branding.

Having boarded the manufacturing train through the production-linked incentives (PLI) scheme and contract manufacturers, the next step is to localise component manufacturing. But given the vice-like grip of the Chinese component manufacturers (arising from their massive volumes, low prices, and deep integration with the global value chains), even countries like Vietnam have struggled to make much headway in component manufacturing.

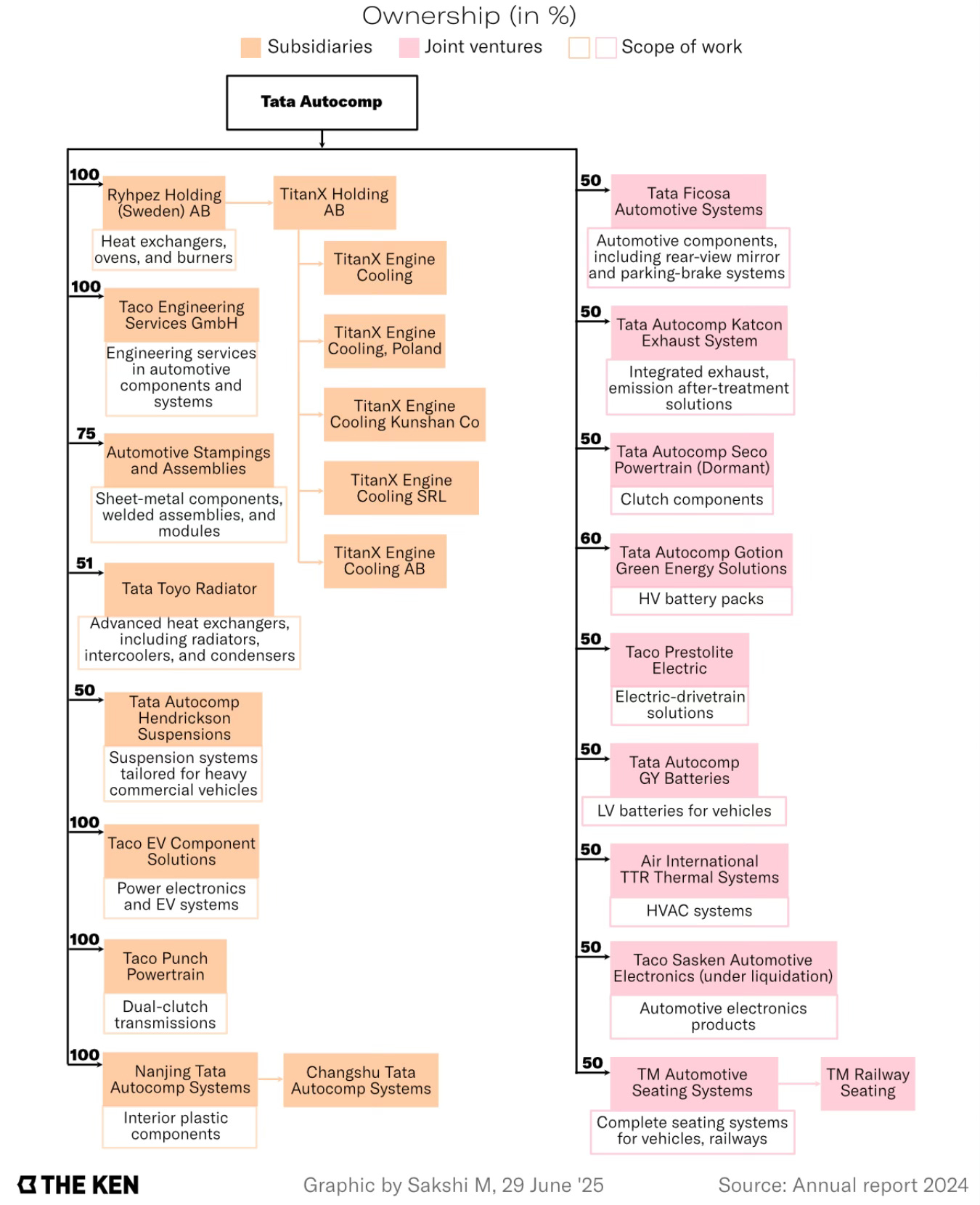

In this context, The Ken has an article on how Tata Motors is tackling the electric vehicle (EV) manufacturing challenge. Central to its EV ambitions is Tata Autocomp, an associate company of Tata Motors (its shareholding is 26%), established 30 years ago to meet the component needs of Tata’s commercial and passenger vehicles. Accordingly, Autocomp delivers EV components to Tata Motors. It had revenues of Rs 13,600 Cr in FY24. Autocomp does this through a “constellation of joint ventures” and subsidiaries.

With over 60 manufacturing facilities globally and a slew of strategic joint ventures, Pune-based Tata Autocomp claims to be one of India’s largest end-to-end EV-component suppliers. Be it battery packs, motors, seats, or even the body of Tata’s EVs, a significant share of it all flows through Tata Autocomp.

And this reflects in Autocomp’s revenue, about half of which comes from partnerships with overseas OEMs.

Tata Motors claims a very high degree of localisation in its Tata Harrier EV model’s drive trains, battery packs, motors, etc., though it’s more likely that many of the components themselves are subassemblies of imported subcomponents. It’s important to make the distinction between components made by Autocomp’s partners globally and in India. It must be critically scrutinised as to how much of the claim of domestic value addition is actual manufacturing and not an assembly subterfuge.

In this context another Ken article has the graphic below which shows how India’s top EV makers mostly rely on outsiders for critical motors (and most certainly battery).

The first article describes the strategy behind Autocomp’s business model.

Building every capability in-house for an EV delays the time to market, says Danish Faruqui, chief executive of Fab Economic, a US-based automotive and gigafactory consultancy, making it difficult to capitalise on evolving demand. “As a result, many auto companies across the globe, including Autocomp, are looking to get external capabilities and turning the EV business into something like an iPhone supply-chain delivery, where the best components are sourced from specific suppliers and the final product is delivered to the customer, bypassing the R&D cost.”

Further, joint ventures give more agility for companies in the short-term. “With technology changing so fast, and cell chemistries and the EV market still evolving, it wouldn’t have been right to invest and develop these in-house while starting from scratch,” Faruqui said. And the other best part of a partnership? The freedom to walk away. Tata Autocomp has already shut down multiple joint ventures, such as Taco Sasken Automotive Electronics (its partnership with Bengaluru-based product engineering firm Sasken Technologies to design and develop automotive electronic products) and Seco Powertrain (a collaboration with the Korean clutch maker Seco Seojin).

The Tata Group is uniquely placed to leverage synergies across the Group companies.

The Tata group’s many companies, spread across 10 sectors, give it an unmatched ability to cross-sell and co-develop. For instance, Tata Motors taps TCS for software; Tata Chemicals for cell chemistry; Tata Power for charging infrastructure; Tata Agratas for cell production; Tata Technologies and Tata Elxsi for design, development, and simulation; Tata Autocomp for hardware; and Tata Capital for loans.

But there are challenges arising from the corporate structure of the Tata Group that are limitations on realising synergies and efficiencies.

Tata Autocomp helped Tata Motors crack the EV code. But here’s the thing: the latter still can’t call the shots on when and how to scale. It’s forced to run at the pace of its other in-house entities… The group is trying to align its moving parts through the “One Tata” approach, a push for internal synergy across entities… But that’s easier realised on Powerpoint slides than on shop floors. “In-house agreements and tech-building often don’t turn out as desirable as designers and engineers want them to be for production,” he added. Essentially, there’s no option to penalise an in-house supplier for any delays… If four to five in-house entities are not performing at the same pace, the whole value chain gets hit.”

This challenge of internal misalignment isn’t unique to Tata Motors. The group’s own super-app experiment, Tata Neu, is a cautionary tale. Despite access to multiple retail brands, the app has failed to deliver a seamless consumer experience, largely due to poor cross-entity integration. Even within Tata Motors, the complexity of managing over 100 entities breeds both independence and inefficiency.

Tata Motors, through Tata Autocomp, may be doing to the creation of EV component manufacturing in India what Apple did with iPhone for mobile phone manufacturing in China, albeit in a completely different manner and at a much smaller degree and scale.

Apple pursued a model of an OEM actively engaging (including embedding its engineers and purchasing some of the equipment) with its contract manufacturers and component makers by building capabilities and handholding them to ensure very high quality. Tata Autocomp is following a vertical integration model of building in-house capabilities through joint ventures and buying up component makers, and then gradually moving their manufacturing (and hopefully design) into India.

This kind of engagement may be essential to develop a component manufacturing ecosystem. It may be necessary that either a large OEM or a vertically integrated corporation provide the de-risking required to attract component manufacturers. By financing and ensuring captive demand, it derisks and encourages component makers to relocate from China. A PLI top-up will be a bonus.

This highlights the importance of large companies in establishing a manufacturing base that is at scale, globally competitive, and strategically significant in key sectors. Apart from EVs, Tatas are now also spearheading India’s mobile phone manufacturing pursuit. Tata Technologies accounted for 26% of iPhones made in India in 2024 and is expanding rapidly.

There’s a strong case that India’s large corporate groups, Ambani, Adani, Mahindra, Birla, etc., could emulate the Tata Group’s EV strategy. The Ambani Group may be well placed to play an important role in petrochemicals, telecommunication equipment, and green energy technologies. Similarly, with the Adani Group in solar cell manufacturing, other green technologies, and smart meters; the Mahindra Group in automobile/EV manufacturing, and so on.

Only these groups have the heft to overcome the coordination problems, financing deep pockets, and risk-aversion to be able to manufacture at a scale that’s attractive enough to break away from the vice-like grip of Chinese manufacturers, and shift component manufacturing in India. Even with the most generous industrial policy and the favourable geopolitical tailwinds of diversifying out of China, there are hard limits to how much industrial policy and market dynamics on their own can go in relocating component makers from China. At the least, the engagement of deep-pocketed corporate groups like Tatas can expedite domestic-scale manufacturing in India.

For countries like India, without any large domestic OEM and without the unique circumstances behind Apple’s engagement with China, local corporate groups may be valuable assets to succeed with the objective of deepening and broadening their manufacturing base.

In this context, there’s always the risk of crony capitalism. Already, there are strong trends of business concentration across sectors in the Indian economy, driven by the large corporate Groups. But this risk cannot overlook the large body of evidence from across the world about the value of large domestic corporate groups in national economic growth. I have blogged on the emerging domestic monopolies in infrastructure and digital markets (also this), the role of family-owned businesses in driving commercial scale across East Asian economies, and the inevitability and need for monopolistic firms in certain sectors.

In this context, a new MGI report highlights the role of a few large firms in driving national economic productivity growth. It finds that a small number of firms contribute the lion’s share of productivity growth and that the most productive firms find new ways to create and scale new value. I’ll blog separately on this report.

No comments:

Post a Comment