In this post, I’ll summarise the issue of the structural imbalances facing the global economy, which manifest in the form of China’s dominance of manufacturing and America’s in consumption. I had previously blogged about these issues here.

Martin Wolf has an excellent article on structural imbalances in the world economy, where he has a graphic that captures the crux of the problem that Trump is trying to address with tariffs.

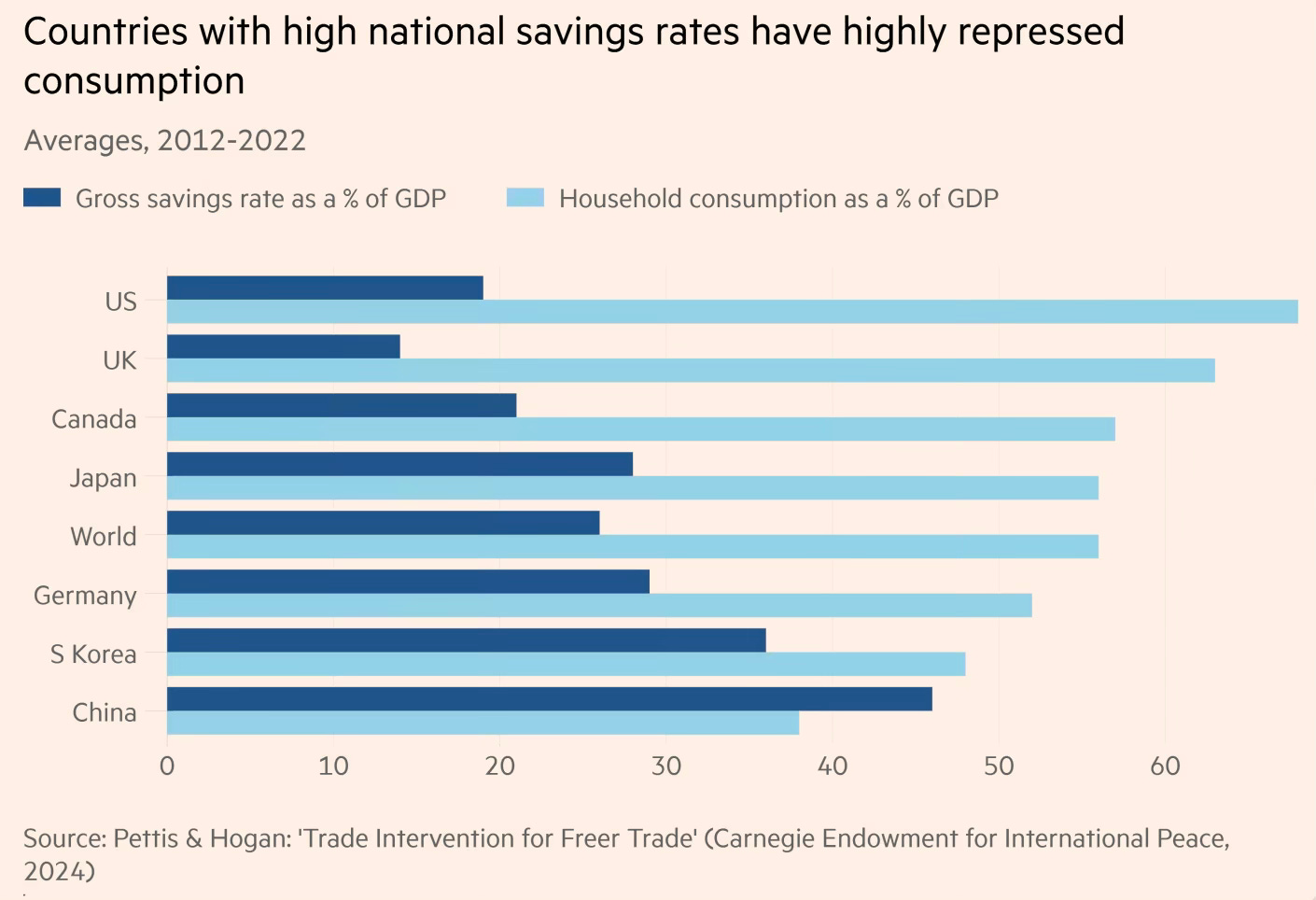

He also cites a paper by Michael Pettis and Erica Hogan to highlight two global macroeconomic correlations, centred around China. One, countries with high savings rates have highly repressed consumption.

Second, countries with low domestic consumption have larger manufacturing sectors.

On the structural imbalance in the US economy, The Economist has a very good description. It says that over-consumption, trade, and foreign borrowings are linked, and “is as if shipping containers arrive in America, unload goods, and then sail back filled with Treasury bills or shares in S&P 500 companies”. It writes,

America’s gross domestic savings are around 17% of GDP, compared with an average of 23% in high-income countries. America invests about 22% of GDP, roughly in line with the rich-world average. The difference between saving and investment is the capital the country must import, which last year amounted to $1.3trn. Meanwhile, America’s consumption as a share of GDP—81% once that by the government is included—is the highest in the G7 apart from Britain. Among the other five big rich economies, the consumption share is on average five percentage points lower.

Relying on net capital inflows has left America with deep financial obligations to foreigners. The difference between the assets that Americans own overseas and those foreigners own in America has fallen to -90% of GDP. This is the kind of “net international investment position” (NIIP) that would be hair-raising in almost any other country. For years America could take solace from the fact that its income statement was healthy. Even as its NIIP worsened, the country earned more on its overseas assets than it paid out to foreign investors. Foreigners own lots of low-yielding debt, including Treasuries; Americans own more stocks and FDI, which have higher yields. The stubborn positivity of the country’s net foreign income has been part of the “exorbitant privilege” that comes from issuing the world’s reserve currency. Yet as the NIIP has lurched into the red, this comfort has dissipated. In the third quarter of 2024 America paid more to owners of its assets than it earned on foreign investments for the first time this century, in part because of higher interest rates…

Mr Trump wants the trade deficit to close, meaning that the financial flows must slow, too. But he also wants America to enjoy an investment boom. The only way to make the equation add up is if America ponies up its own capital by saving more. In other words, it must cut its consumption.

The article underlines the importance of America’s credibility in ensuring it’s able to pull of a smooth landing on its massive structural imbalances.

The $62trn-worth of American capital owned by foreigners is distributed across tens of millions of balance-sheets belonging to firms and individuals. A third is debt instruments that cannot be marked down as seamlessly as equity prices or property values; of that debt, two-fifths is government-issued. Moreover, since America’s debt liabilities are mostly denominated in dollars, it should always be able to honour them, at least in nominal terms.

But a loss of faith in America’s ability to deliver the necessary real returns for foreign investors could cause a large depreciation in its asset prices, which have reached eye-watering highs. The country’s bonds, properties and stocks, as well as the dollar itself, would come under intense selling pressure. A much weaker dollar and lower prices for American bonds and stocks would force a rebalancing by reducing the size of America’s external liabilities relative to its external assets. Tighter financial conditions would discourage consumption, whipping the current account into line no matter how uncomfortable such a sudden adjustment would prove.

The question for America, and indeed the global economy, is whether it can defuse its external liabilities without paying such a steep price… Tariffs discourage consumption by raising prices and hurting living standards. Barriers to capital mobility, the first signs of which are buried in Mr Trump’s tax bill, force up domestic interest rates and encourage domestic saving… It makes Americans poorer, and by imperilling the returns earned by foreign investors, threatens to bring about the very crash rebalancing is supposed to prevent… A smoother adjustment—one that does not seek to make America a creditor nation overnight—should be possible. If faith in the country is maintained, its exorbitant privilege means it ought to be able to repay its foreign debts with smaller trade surpluses than other countries, says Menzie Chinn of the University of Wisconsin-Madison. If America avoids sullying its own assets, it can afford to be gradual in its transition towards a trade surplus.

Let me explain these structural imbalances in greater detail.

There exist two major structural imbalances in the world economy. The first concerns the imbalance between consumption and investment, and the second concerns that between savers and lenders. They are also linked to each other. While there are also contributors like globalization, trade liberalization, technological advances, and demographics, these imbalances have become excessive enough to spill over as trade wars due to the policies pursued by governments across the world. Reversing these policies is important to addressing these imbalances.

Let’s start with the first. A fundamental problem facing the world economy is the structural imbalance between consumption and investment among countries. The consumption share of national economic output is disproportionately low in some countries, while the investment share of output is similarly excessive. Similarly, some countries with the fiscal space for public investments underinvest in public goods despite having large investment requirements while pursuing economic growth through exports.

The most totemic example, of this consumption-investment imbalance is China. Since the beginning of its current growth phase, the country has maintained investment rates of over 35% of GDP, rising to touch 45% of GDP since the Global Financial Crisis. However, its consumption share of GDP has stayed at a remarkably low 35-40% of GDP, at least a third lower than that for other major developed and developing economies. All told, in 2024 while China accounted for 32% of global manufacturing, double that of the US, it represented only 12% of its consumption.

The percentage of Chinese households who had out-of-pocket health spending greater than 10% of total household consumption rose from 20.4% in 2007 to 21.7% in 2018, compared to the global average of 13.2% in 2017 and 7.7% and 1.5% respectively for Russia and Malaysia, two countries with similar per capita GDP as China. Compounding matters, the Chinese government spends only 6% of GDP on individual consumption (services ranging from healthcare to social security), an outlier among major economies and lower than even similarly placed economies. The low public spending forces precautionary savings.

This imbalance has also been sustained by financial repression that keeps interest rates low, the hukou system that restricts access to welfare benefits and reduces consumption, wage controls and other measures that help businesses access a huge class of cheap and mobile industrial workers, inadequate public health care and social safety nets that lead to forced savings, artificially inflated property markets that allows local governments access to plentiful credit, and a shadow banking system and off-balance sheet financing entities that compromises financial discipline and funnels credit. For all these reasons, China is often referred to as a country with a rich government and poor citizens!

This imbalance has reduced domestic demand and channeled manufacturing towards an excessive reliance on exports. It has resulted in China consistently running large trade surpluses, which recently hit an astronomical trillion dollars in 2024.

The imbalance on investment has also been turbocharged by China’s search for alternative engines of economic growth after the real estate crisis that erupted in 2021 with the default of the Evergande Group, the country’s second-largest property firm. Beijing re-directed the large volumes of credit away from real estate towards manufacturing, especially solar, batteries, automobiles, and electric vehicles. Chinese companies rapidly built massive over-capacity which they started exporting at discounted prices, thereby further tilting the playing field towards them and against their competitors in their domestic markets.

China is not alone here. Germany, the largest economy in Europe and for long the engine of European economic growth, has pursued rigid and excessively conservative balanced budget policies. These policies have meant that successive governments have avoided the much-needed public investments in replacing ageing infrastructure facilities and expanding them to meet emerging requirements. This, in turn, has depressed consumption and, like with China, channeled an increasing share of the output of the highly competitive German manufacturing firms towards exports. Germany’s domestic consumption share of the economy at slightly below 50% of GDP in 2023 was the lowest among all G-7 economies and has been continuously declining in the last four decades. The result has been a consistent trade surplus for decades, if only on a smaller scale than China.

The consumption-investment imbalance in countries like China and Germany has been complemented by a similar imbalance in the opposite direction in the US. The cheap imports from China allowed American consumers in particular and their Western counterparts in general, to enjoy and gradually get addicted to good-quality products at very low prices. Their businesses similarly maximized profits by using cheap Chinese inputs and products. It allowed central banks and governments to take disproportionate credit for low inflation and high economic growth rates driven by consumption (and debt, which we discuss next).

This imbalance is also a reflection of the skew in the economic structure of countries like the US, where the non-tradeable services sector has taken a disproportionately high share of the output. A consumption culture that prioritises services tends to squeeze resources from going into tradable manufacturing. This imbalance can also arise when aggregate demand exceeds output, like with a US economy that has been operating close to full employment for a few years.

This imbalance is closely linked to the second imbalance between savers and lenders. China’s Gross Domestic Savings as a percentage of GDP has been in the range of 40% since the eighties and rose above 50% of GDP in the aftermath of the GFC and has remained above 45% since. Financial repression meant that Chinese households have limited avenues to savings outside of the banking system that pays low returns. The hukou system, inadequate welfare and social safety benefits, and high property prices have amplified savings while also depressing consumption. Meanwhile, in countries like Japan, worsening demographics led to reduced investment opportunities and lower returns.

The trade surpluses retained in the country add to their central bank reserves. These reserves, in turn, had to find investment opportunities outside the country. Their safety and liquidity made the US Treasury Bonds the most common and convenient investment opportunity for global central bank reserves. All of this has resulted in what Ben Bernanke famously described as a “global savings glut”. The global financial market integration promoted by institutions like the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has amplified the global cross-border financial flows. The extended period of outperformance of US equity markets and the strong performance of the US economy have made it the most attractive global investment destination.

These inflows have also allowed the US government to borrow at very low rates despite running up large deficits. They have led to a surge in the US debt-to-GDP ratio from 67.5% in 2008 to just below 125% in 2024. Fiscal deficits in the US have risen sharply in recent years, and was over 6% in 2024. A similar trend of rising debt-to-GDP ratios is observed across many developed economies, with the trend having become especially pronounced since the global financial crisis. This also coincided with the period of rising trade surpluses of China and Germany.

In simple terms, the US’s roles as the largest import market, a form of global buyer of last resort, and as the largest borrower, a haven for lenders, are two sides of the same coin. It borrows to buy. Its exorbitant privilege from the ownership of the global default reserve currency coupled with the global savings glut, allows the US government to continually borrow in its currency at cheap rates. The apparently never-ending rise of its equity markets, coupled with the depth of its financial markets, make it the standout investment destination for foreign portfolio investors. At the same time, the strength and dynamism of its economy make it the most attractive destination for foreign direct investments and private equity investors.

The underlying trade and financial transactions reflect an accounting reality that links the two imbalances. The total amount of money coming into a country must necessarily be balanced by that leaving the country. In other words, the current and capital accounts must be equal, or the balance of payment must be zero. This means that if a country runs a large trade surplus, it must necessarily be exporting capital, and similarly, trade deficits go alongside capital inflows.

Underlying these structural imbalances is a more fundamental imbalance, one that manifests across several problems faced by modern society. It’s that of a global economic system that has become unhinged in the pursuit of efficiency and profit maximization and has traded off resilience and equitable distribution of returns to capital. It manifests in the worrying trends of business concentration across industries, widening inequality, and the emergence of a small group of staggeringly wealthy plutocrats.

The most important trends of the global economy since the turn of the nineties have been the globalization of value chains, offshoring and outsourcing, trade liberalization, financial market integration, financialization, and increased immigration. While these trends have contributed to the unprecedented period of global economic growth and prosperity, they have also triggered self-reinforcing dynamics that have taken each of them too far down the road with disturbing consequences and incentive distortions. As the cliché goes, too much of a good thing is a bad thing!

No comments:

Post a Comment