A feature of the efficiency-maximising (American version) capitalism is the trend of business concentration at the extensive and intensive margins. The former involves horizontal integration, whereby a handful of firms make up an increasingly major market share in their respective industries. It’s a phenomenon that spans industries and countries in varying degrees. The latter refers to the trend of vertical integration, where the dominant firm tends to capture an increasing share of value addition within the industry. This feature is pervasive in certain sectors like IT, healthcare, infrastructure, etc.

The Ken has a story on the rapid changes in business models in the airport services industry due to the increasing dominance of the Adani Group. The predominantly outsourced model of services in the airport industry in India is giving way to a more vertically integrated model.

Traditionally, the various non-aeronautical services in the airport, like lounges, food and beverages (F&B), retail, etc., were outsourced to specialised service providers who in turn contracted with aggregators who brought together brands (like banks for lounges, retail brands for F&B and retail space, etc.). This is now giving way to a strategy where the real-estate concessionaire (Adani Group) is seeking to maximise value capture from airport services by creating its own service companies and squeezing out the outsourced service providers.

The article narrates the story of Dreamfolks Services.

Dreamfolks Services, a publicly traded company that has quietly built a 90% monopoly in the lucrative business of getting Indian credit-card holders into airport lounges. It sits in the middle of a four-way handshake among banks, card networks, lounge operators, and travellers… TFS and Encalm ran the physical lounge spaces. But it was aggregators like Dreamfolks that unlocked access by bundling lounge networks and partnering with banks and credit-card issuers. If a lounge visit costs Rs 100, the aggregator might charge Rs 115, pass Rs 5 back to the operator, and keep the rest. Banks liked the convenience. Aggregators liked the margins… Around them, a cottage industry of brands and partners grew…

Liberatha Peter Kallat, the company’s founder and chairperson, appeared on CNBC TV-18 and accused Adani Airport and the second-largest airport operator, GMR Airports—without naming them directly—of pressuring banks like ICICI and Axis to abandon aggregators like hers in favour of themselves… Travel Food Services (TFS) and Encalm Hospitality, both prominent lounge operators, have since cut out Dreamfolks and signed directly with Adani. Banks are following suit… As tech infrastructure improved, there was no longer a strong reason to maintain the middle layer… every airport and lounge operator is now building its own backend.

It describes how in-sourcing is happening across service verticals.

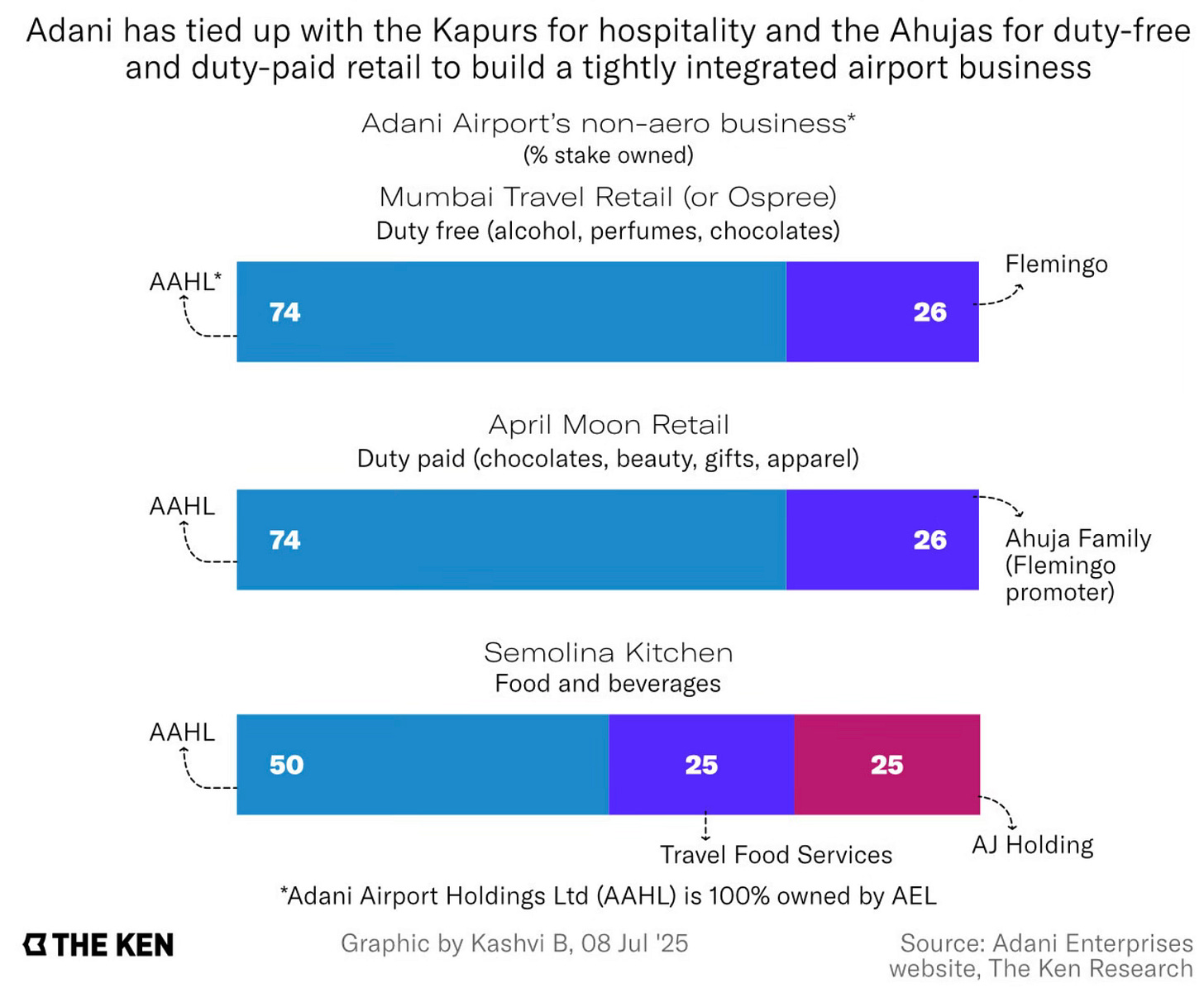

Unlike Adani’s other airports, where retail concessions are often managed by third parties, in the Mumbai airport, Adani directly runs the non-aero business… Adani Airport has moved to a franchisee model—a shift from the earlier system, where brands paid rent (fixed or revenue-linked) to concessionaires who had won competitive bids for spaces. Now, instead of paying rent, they are licensing their brand to the airport and letting it run the show…

In Mumbai, three large players—TFS, Lite Bite Foods, and Devyani International—used to dominate F&B. That has changed. Last March, Adani acquired a majority stake in Semolina Kitchens, a TFS subsidiary. TFS, now aligned with Adani, is emerging as the primary F&B operator at the airport. Lite Bite’s share has reportedly fallen from 50% to under 20%, said F&B operators in the know. Both it and Devyani are expected to exit entirely once their contracts expire later this year…

Of the eight lounges at the Mumbai airport, at least five are now managed by TFS. Through Semolina, TFS has lounge and Quick Service Restaurant (QSR) concession rights at six Adani-operated airports, as well as Goa (operated by GMR), according to its pre-IPO documents. The roles are consolidating. The partners are getting fewer. The integration is getting tighter… So if a brand is trying to operate at the airport, they can’t be surprised if the space goes to TFS’s in-house brands like Caffecino, Curry Kitchen, or Dilli Streat instead…

Over the past 18–24 months, categories like watches, apparel, cosmetics, salons, and even convenience stores have seen a shift in how business is done at Adani-run airports. The model is familiar by now: migrate the old setup into a new one, run by a close partner. In this case, that partner is April Moon Retail, claimed multiple brand owners. Stores at these airports still carry their logos and branding, but the backend has moved, they said. Employees are now on April Moon’s payroll. Bills carry the brand’s name, but the GST number belongs to April Moon…

April Moon has begun launching in-house formats across categories. Stores like Bon Voyage, which sell everything from snacks and books to travel accessories, now operate across multiple Adani Airports… What’s really taking off is the retail-cloning strategy. When something sells well at the airport, it doesn’t take long for a lookalike to show up—all run by April Moon. A luxury watch counter resembling Ethos or Helios? That’s Meridiem. A beauty and cosmetics outlet that looks like Nykaa? Meet Amara Luxe. Something that feels like Lenskart or Titan Eye+? It’s probably Vue De Luxe. Handicrafts à la Rare Planet? That’d be Pravasi. There’s even talk of a Hamleys knockoff said to be in the works.

This trend, in turn, creates several disturbing concerns.

TFS, whose IPO opens on 7 July, was founded by the Kapur family—the same folks behind Copper Chimney, Bombay Brasserie, and The Irish House… TFS could eventually be replaced, too. Adani is reportedly talking to Plaza Premium, the global lounge operator, for future airport lounge ops…

April Moon began appearing around 2021. Its role was to take over the duty-paid retail at airports. That September, Adani acquired a 74% stake in Flemingo Travel Retail—a global duty-free operator founded by Atul Ahuja—for just Rs 2.8 crore. This, for a company that had clocked nearly Rs 900 crore in revenue in FY19. The deal, struck mid-pandemic when travel retailers were reeling, came at a throwaway price. And it gave Adani near-total control over both duty-free and duty-paid retail. For brands, that left little room to negotiate: either go through April Moon, or lose access to airport shelves… “If we made Rs 15 lakh in monthly sales at a store, we’d only be allowed to record Rs 5–6 lakh,” said one retailer. After costs, they say, the effective take-home margin is 5–6%. “Retailers who spent decades building these brands are now effectively just vendors.”

Strong financial incentives are driving these trends

At AAI airports, non-aeronautical revenue makes up maybe 10% of the pie. At private airports like Mumbai or Delhi, that jumps to 62%, per data cited by Crisil in TFS’s IPO documents. And within that, F&B alone account for as much as 40%. For instance, the top five Starbucks outlets in India by revenue are all located at airports, according to an F&B operator. A single store can bring in Rs 1.5 crore a month; that’s 3–4X more than a high-street outlet. And margins are nothing to sneeze at. A Rs 400 latte at an airport (Rs 350 at other outlets) contains roughly Rs 20 worth of ingredients.

Business concentration through horizontal and vertical integration may be inherent to the dynamic of capitalism with its profit-maximising firms. And there are doubtless efficiencies to be realised from both these trends.

But the case of the airport sector in India, representative of trends across several sectors, raises questions about the stifling of entrepreneurship and innovation, and business dynamism in general.

For example, what’s the incentive for entrepreneurs to start something like Dreamfolks Services, or April Moon Retail, or TFS, if there’s an imminent threat of being squeezed out of the market or being taken over by the dominant airport operator? Wouldn’t such trends deter investors from putting their money behind entrepreneurs whom they would otherwise have supported? More generally, is business concentration at the extensive and intensive margins likely to scare risk capital away from these sectors?

In addition, there’s a compelling argument that vertical integration under a corporate behemoth would lower innovation, service quality, and sector-wide dynamism. There’s a strong likelihood that once these services are taken in-house, like with all monopolies, the airport operator will have diminished incentives to pursue innovation and service quality and instead will have increased incentives to maximise profits.

In any case, it’s unlikely that large infrastructure groups or their subsidiaries will be as innovative or driven to improve service quality (say, cater to all market segments), expand service portfolios (including interoperability with similar services globally), explore adjacent market synergies, and so on. This has been the global experience from across sectors, especially but not only in the infrastructure sector, over time.

It’ll be easy for the airport industry in India to become entrapped in a sub-optimal equilibrium of a horizontally and vertically integrated market dominated by a couple of operators. Given the inevitable growth in traffic due to economic growth starting from a low baseline, the associated inefficiencies can be papered over for a long time. But its opportunity cost can be considerable.

Vertical integration also creates problems with the transparency of accounting for all those involved. Being part of the same corporate group means that there will be incentives to indulge in manipulation of accounts to minimise statutory payments and taxes, besides also maximising leverage. The operator can show lower revenues by over-invoicing and shifting profits to subsidiaries. Entities within a corporate group can do tax arbitrage by shifting profits among themselves.

There’s also the case that horizontal integration creates the incentives for vertical integration. Adani Airport will have the incentive to in-source hitherto outsourced airport services only if it enjoys the economies of scope and scale from operating multiple airports. This underlines the importance of controlling market shares in such technically monopolistic markets (which also include those in IT, which benefit from network effects).

However, concerns about business concentration must be balanced with the need for large capital, a high risk appetite, and business ambition, especially if the objective is to scale big and rapidly. The country’s rapid and high growth ambitions require massive investments. The government is expanding airports at a rapid pace, and the airline industry is expected to grow fast for several years. Given their long gestation and deep exposure to the business cycle, only businesses with a high risk appetite and access to patient capital will invest in these sectors.

Take the example of smart meters. The Government of India wants to install bi-directional smart meters in all 250 million households by the end of 2026. Even at a very conservative Rs 10,000 per smart meter (and its allied components), this would require a staggering investment of Rs 2500 billion (or about $28 bn). Given that regulatory conditions would restrict the discoms from recovering the cost of these new meters from existing metered customers, this cost must be borne by the government or the discoms.

Since mobilising upfront capex of this scale would have been impossible, a totex model was adopted where the major share of capex would be borne by the concessionaires who would recover it over the eight years of the contract. This also means that the concessionaires would have to bear the significant risks (technology obsolescence, political economy of electricity tariffs, policy shifts, and local politics) involved and carry them in their balance sheets over the contract period. Only a few firms with the deepest pockets and highest risk appetites can assume such risks and make money from these contracts.

In conclusion, business concentration poses a dilemma for policy-making in many sectors. Its harms are well-known and often salient in a bad way, but its benefits are less known. When it unleashes a dynamic that confines an increasing and dominant share of the benefits in the hands of a few corporate groups, then there will be problems.

Econ 101 would have it that such monopolistic trends should be formally regulated. But regulation is fraught with problems, given its inefficiencies and the political economy. Besides, there are limits to the extent of regulation required to control these business dynamics.

From another perspective, the reliance on large corporate groups to drive high-growth aspirations is essentially a legitimate political economy choice that many countries, including those in the West, have made in their growth trajectories. Therefore, it’s only natural that a recognition of the problems that accompany the pervasiveness of large corporate groups be met with a similar political economy choice to force some form of restraints on their overreach.

No comments:

Post a Comment