The primary international trade challenge facing countries in manufacturing is that they must compete with China. To achieve this, they must bridge a significant competitiveness gap. Econ 101 points to increasing productivity (through the likes of improving worker skills and using the latest technologies), investing in infrastructure, lowering the cost of capital, and easing regulations.

This overlooks an important aspect. A critical requirement to compete with China is to maximise economies of scale. In most sectors, this, in turn, cannot be achieved without being export-focused. This, in turn, draws attention to export promotion policies, especially important to bridge the competitiveness gap arising in particular from China’s massive economy-wide indirect subsidies.

This is especially important with component manufacturing, the next stage of value addition in India’s manufacturing strategy. The low domestic market volumes and the need to maximise economies of scale mean that Indian manufacturers must aim to Make in India for the World.

India does not have anywhere near the fiscal resources to match China in providing economy-wide subsidies. It must rely on direct and targeted export subsidies. But, despite the near complete paralysis of WTO and egregious violation of its provisions by the major economies (read US and China), India has been surprisingly reluctant to support industrial policies that support the promotion of exports.

The WTO’s Subsidies and Countervailing Measures (SCM) Agreement categorises two kinds of “prohibited” subsidies - those “contingent on export performance” (Article 3(1)(a)), and those “contingent on the use of domestic over imported goods” (Article 3(1)(b)). It allows for subsidies that are specific to enterprises, industries, and regions. When the SCM and other WTO Agreements were being negotiated in the nineties, it was thought that only the subsidies contingent on export performance would be trade-distorting in any significant manner. It was also thought that the subsidies specific to enterprises, industries, and regions (or the economy as a whole) could not be sustained at the scale required to distort trade in particular products, much less global trade in general.

China has proved otherwise. This necessitates a wholesale revisit of the WTO itself.

In this context, it’s useful to place the issue of trade-related (or export promotion) subsidies in perspective.

For a start, as Lorenzo Rotunno and Michele Ruta show, there has been a sharp rise in the use of domestic subsidies in industrial policy, especially aimed at manufacturing, and by developed and emerging economies. They categorize subsidies into four groups - production subsidies, direct transfers (including state aid and grants), policies resulting in a loss of government revenues (tax breaks), and policies wherein the government assumes risk related to the beneficiaries’ actions (loans).

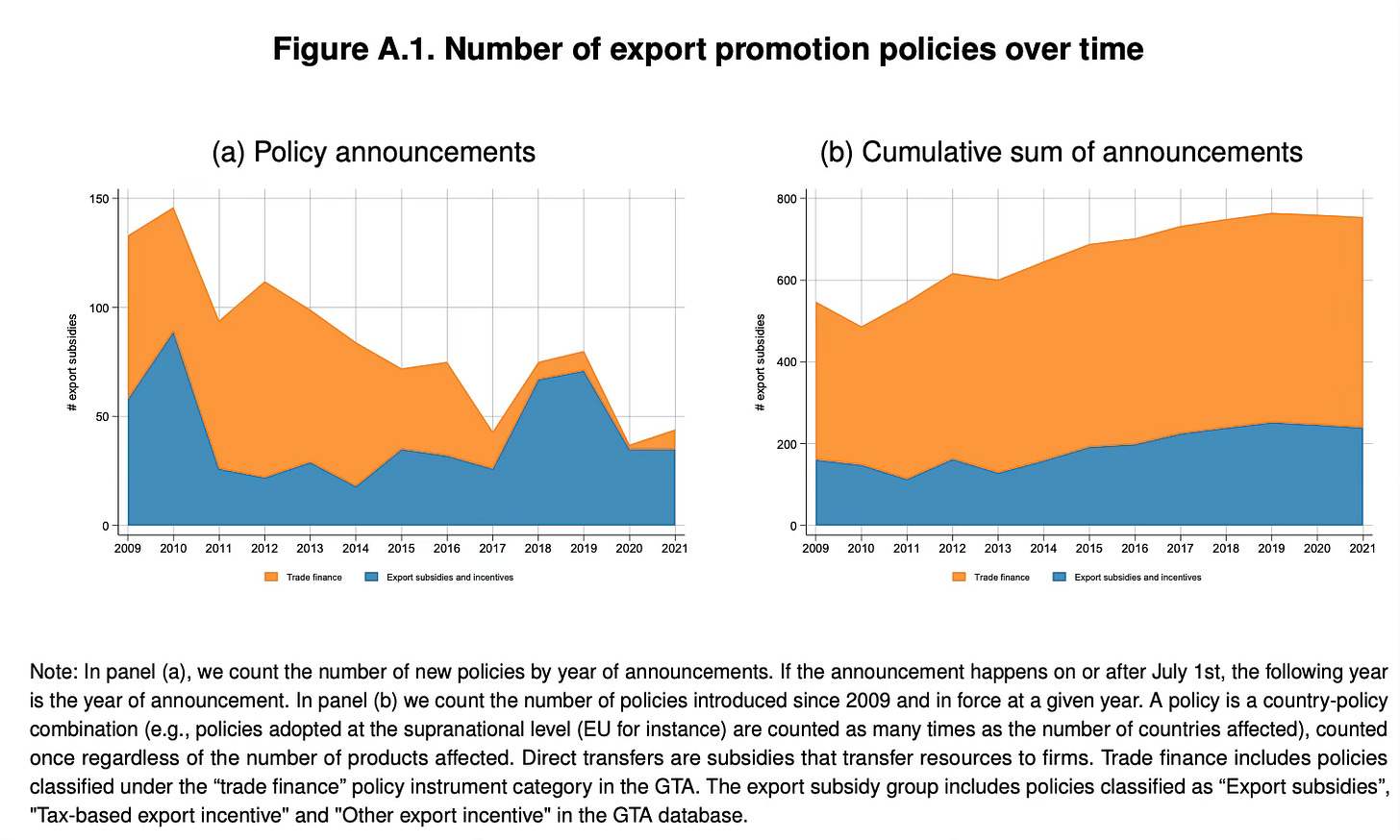

They show that trade finance and export subsidies and incentives are the two main types of export promotion policies. While both have declined over time, the latter now dominates and is still employed by several countries.

They analyse the impact of domestic subsidies on international trade flows.

Exports of subsidized products from G20 emerging markets increase 8 percent more than exports of other products, with no evidence of selection. The gravity estimates confirm that subsidies promote international relative to domestic trade. These spillover effects are concentrated in some industries, such as electrical machinery, and are stronger when subsidies are given through tax breaks than other policy instruments.

Reka Juhasz and co-authors have a new paper that uses supervised machine learning tools on data from policy announcements in the Global Trade Alert (GTA) database to analyse policy language (instead of policy instruments) to categorise industrial policies (IPs) across the world over the 2010-22 period. They define industrial policy as deliberate government action aimed at altering the composition of the domestic economy to achieve a public goal. Their findings:

The new data on IP suggest that i) IP is on the rise; ii) modern IP tends to use subsidies and export promotion measures as opposed to tariffs; iii) rich countries heavily dominate IP use; iv) IP tends to target sectors with an established comparative advantage, particularly in high-income countries.

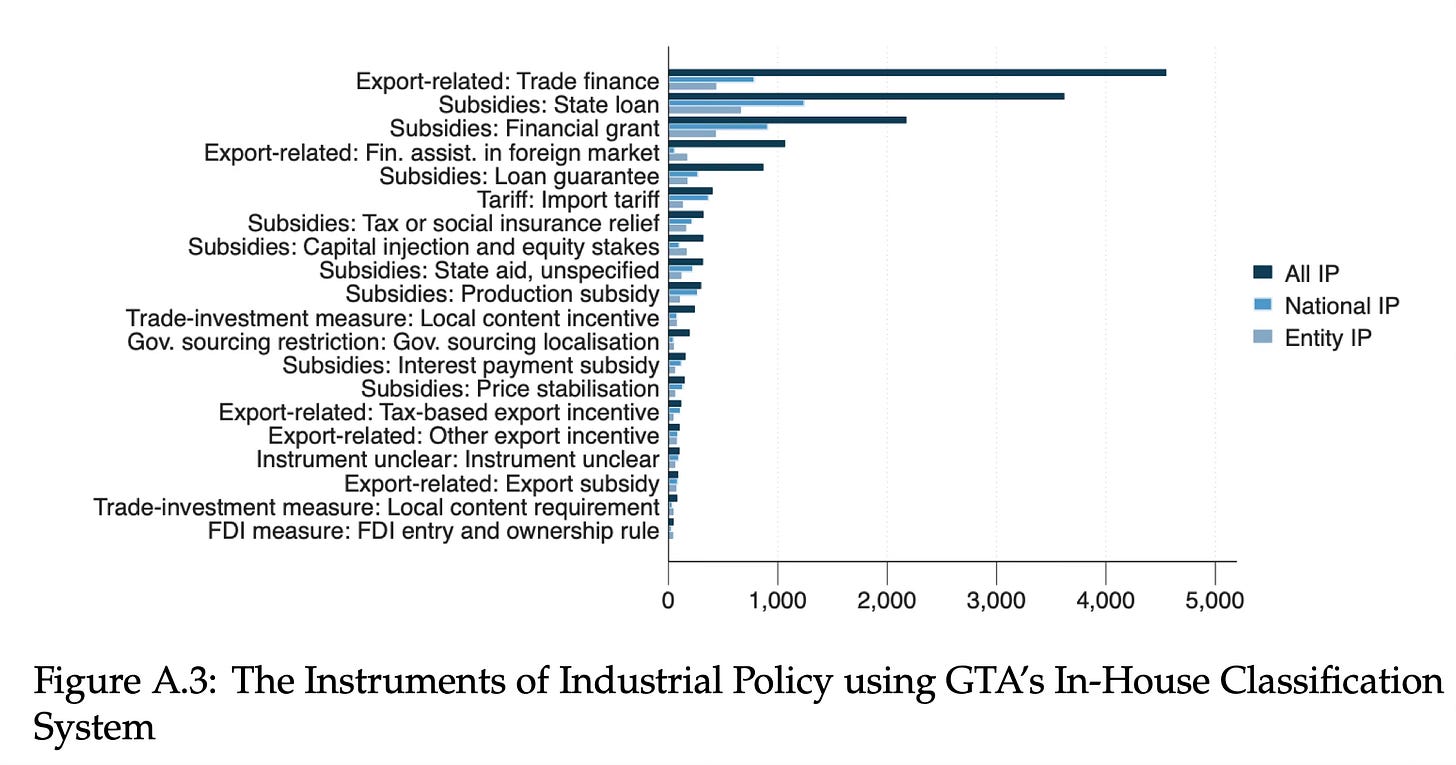

The graphic below points to the eight most commonly used industrial policy instruments, which highlights that export-related measures (mainly trade financing) are the second largest category of IP interventions. In fact, export-related measures run a close second to non-export subsidies among IP interventions.

This figure reveals that most export-related IP measures are deployed via trade-financing, and, to a lesser extent, financial assistance in foreign markets… export-related IP measures tend to operate by providing financing as opposed to directly incentivising exporting… much industrial policy seems designed to facilitate participation in export markets... Finally, this finding highlights that modern industrial policy requires fiscal resources and high administrative capacity. Specifically, states need sufficient fiscal revenue to subsidize firms and promote exports, as well as the administrative capacity to identify which firms to support.

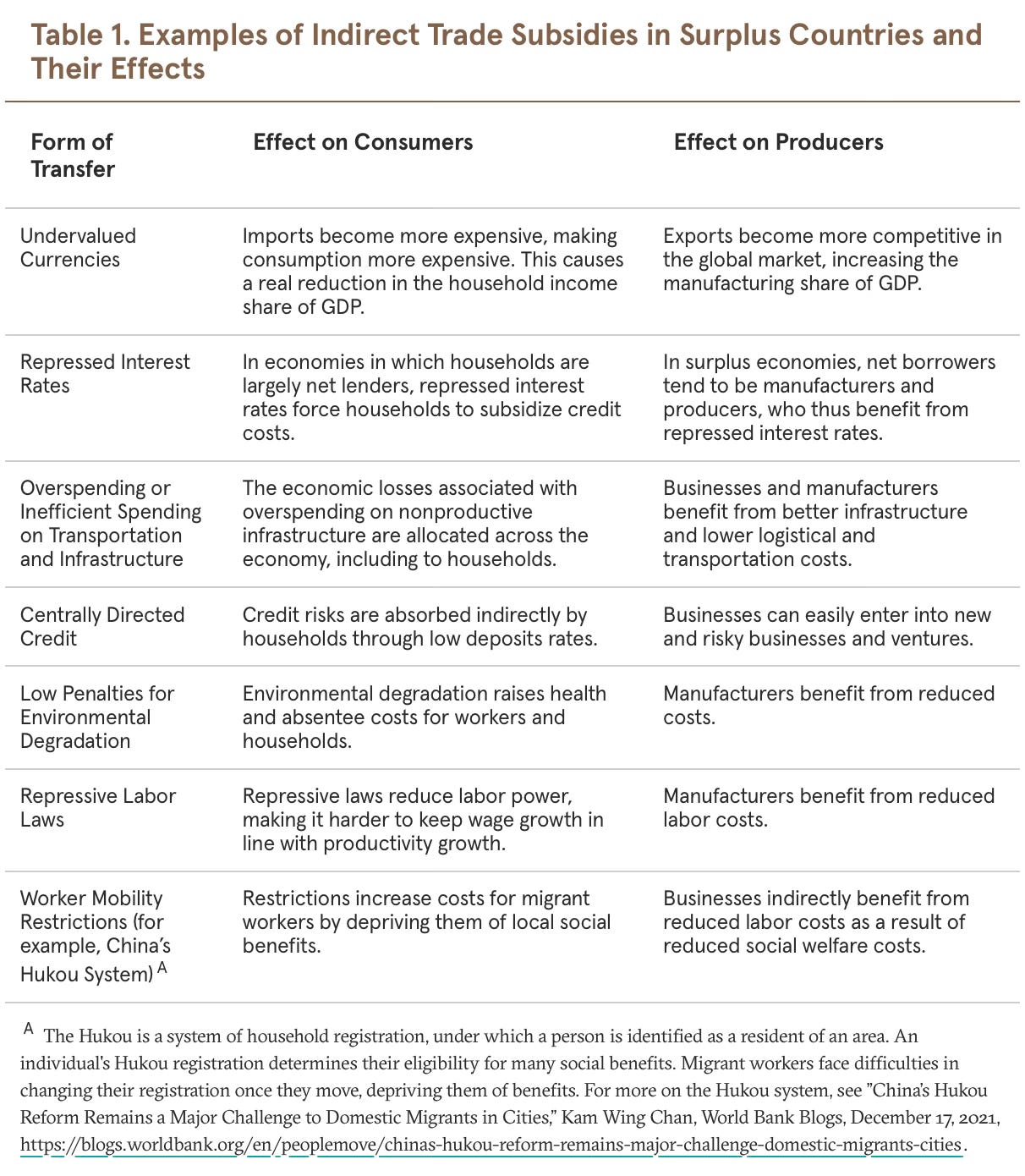

Michael Pettis and Erica Hogan point out that focusing on direct subsidies conceals the true extent of trade-distorting subsidies. Instead, they show that indirect subsidies have become the main instruments of export promotion. The table below captures commonly used indirect trade subsidies.

For example, surplus economies typically have undervalued currencies as part of their trade strategies. Having an undervalued currency subsidizes manufacturing at the expense of households because households are all net importers—as they do not produce for the purpose of exporting—while net exporters are mostly manufacturers. An undervalued currency makes the manufacturing sector in that country more competitive, while reducing households’ consumption capacity… repression of interest rates below the neutral real interest rate has also been a powerful cause of financial transfers from household savers to manufacturers, as seen in Japan in the 1980s and China in the 2000. Further, overspending on transportation and infrastructure serves as an especially significant transfer from households to manufacturers in China today. Other transfers include centrally directed systems of credit, low penalties for environmental degradation, repressive labor laws, and restrictions on worker mobility.

They argue that such indirect subsidies constitute a transfer of wealth from households to manufacturers. They write

Economies that heavily subsidize manufacturers at the expense of households will typically have: larger manufacturing shares of GDP than their trade partners, since manufacturers must migrate to jurisdictions where workers are paid the lowest relative to their productivity to remain globally competitive in a hyper-globalized world; lower consumption shares of GDP than their trade partners, reflecting the cost of the subsidies on consumers; and large, persistent trade surpluses, as the repressed household income used to pay for manufacturing subsidies makes it impossible for domestic household consumption to balance trade. When all three conditions hold, it is almost certain that repressed household demand is subsidizing manufacturing. And, indeed, we see this reduction of household consumption and increase in trade reflected in economic data for surplus countries (and the opposite trend for deficit countries).

Yet another instrument used by China to distort trade is its State Owned Enterprises (SOEs), which systematically cut back on imports during trade wars. Chinese SOEs make up a fifth of Chinese imports from the US, providing the country with a valuable trade policy instrument that others don’t have.

Felipe Benguria and Felipe Saffie examined the period from early 2018 when the first Trump administration initiated a trade war with China, and found that US exports fell relatively more during the trade war in products with a high Chinese import share by SOEs. It found that while tariffs account for an 8% reduction in trade, SOEs account for another 4% decline. They also find that the period of decline in US exports to China in sectors with a higher SOE share also saw an increase in Chinese imports from the rest of the world, pointing to further evidence in favour of the SOE effect.

They write also about how China may have used its SOEs as a retaliatory weapon against the US tariffs.

We have also found evidence that the SOE effect was stronger among industries located in Republican–voting US counties, suggesting a political motivation just like the literature has found for tariffs. Our work is the first to provide evidence on the use of state–owned enterprises as tools of trade policy, in any context… We have shown that while US exports facing Chi- nese tariffs were gradually rerouted toward other markets, this was not the case for exports facing the reduced demand by Chinese SOEs.

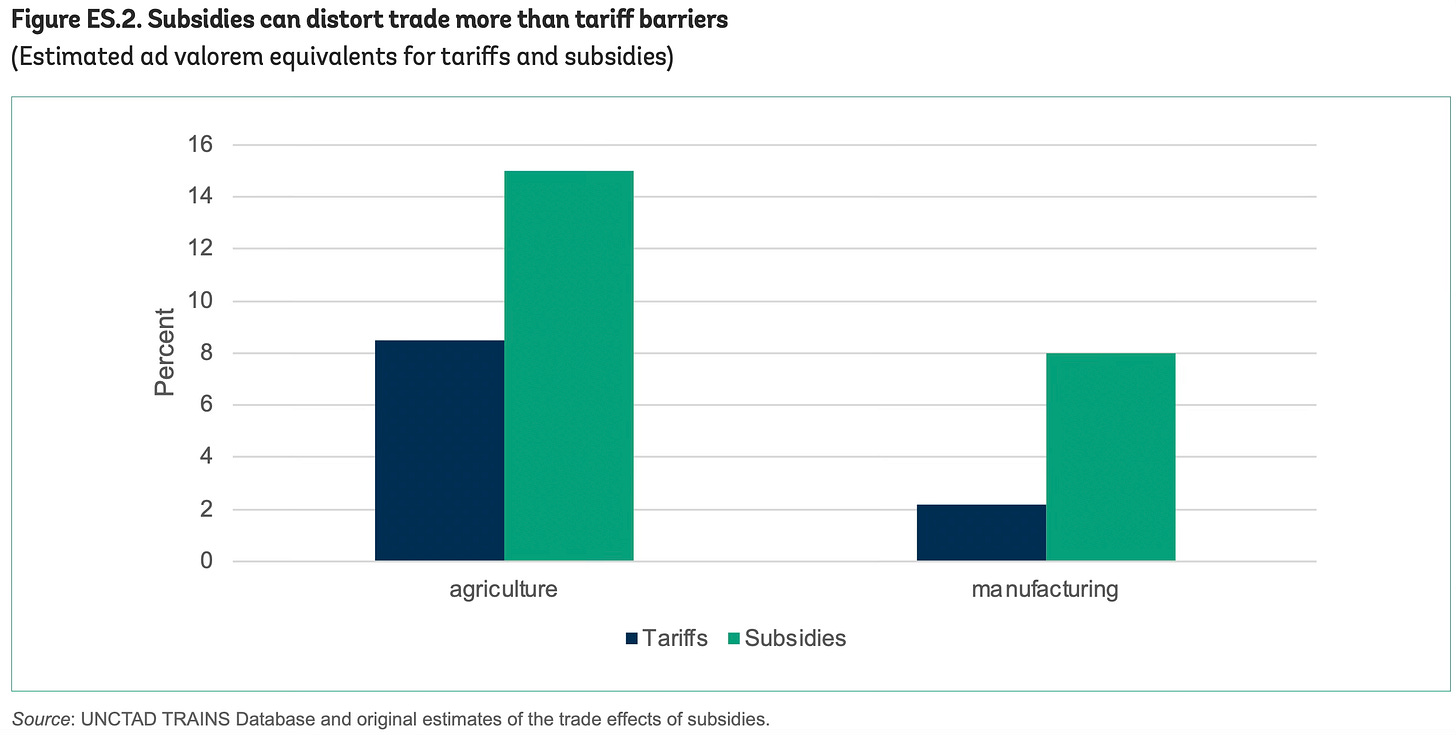

A World Bank report finds that subsidies have larger trade-distorting effects than even tariffs.

Subsidies create trade-distorting effects for both agriculture and manufacturing exports... Subsidies can be more distortive to trade flow than existing tariffs barriers. The distortionary effect of subsidies on trade, expressed in ad valorem equivalents, is estimated at 15 percent for agriculture and 8 percent for manufacturing… Trade-distorting subsidies can displace trade and production in other trading partners, with important repercussions for developing countries… A disproportionally large number of programs are implemented by major trading countries that have the economic heft to distort global markets for goods and services.

It also finds that the prevailing global trade rules are ill-equipped to deal with subsidies. As indirect subsidies have become the main distorting factors in international trade, and also given its own current dysfunctional state, it’s time to revisit the WTO’s provisions.

In any case, since 2019, after the US refused to allow appointment of members to the Dispute Settlement Body that hears appeals from members, the WTO has become a toothless organization. This has also encouraged a revival of bilateral and multilateral associations, and countries have come together to also settle their disputes through negotiations. This trend will only be accentuated as the US under President Trump becomes more and more unilateral in its trade engagements. In fact, the reciprocal tariffs announced by the US signals a clear regime shift back to the pre-WTO era.

No comments:

Post a Comment