In the context of the debate on deregulation, internal trade barriers are a significant but less discussed cost.

This blog post by Luis Garciano (HT: Marginal Revolution) points to an IMF report that looked at internal barriers to trade within the European Union (EU) and found them to be equivalent to tariffs at 45% for goods and 110% for services.

The IMF report finds that while trade costs for goods dropped 16% for EU imports, they fell only 11% for internal EU trade. It finds that internal trade among EU countries is less than half that between US states.

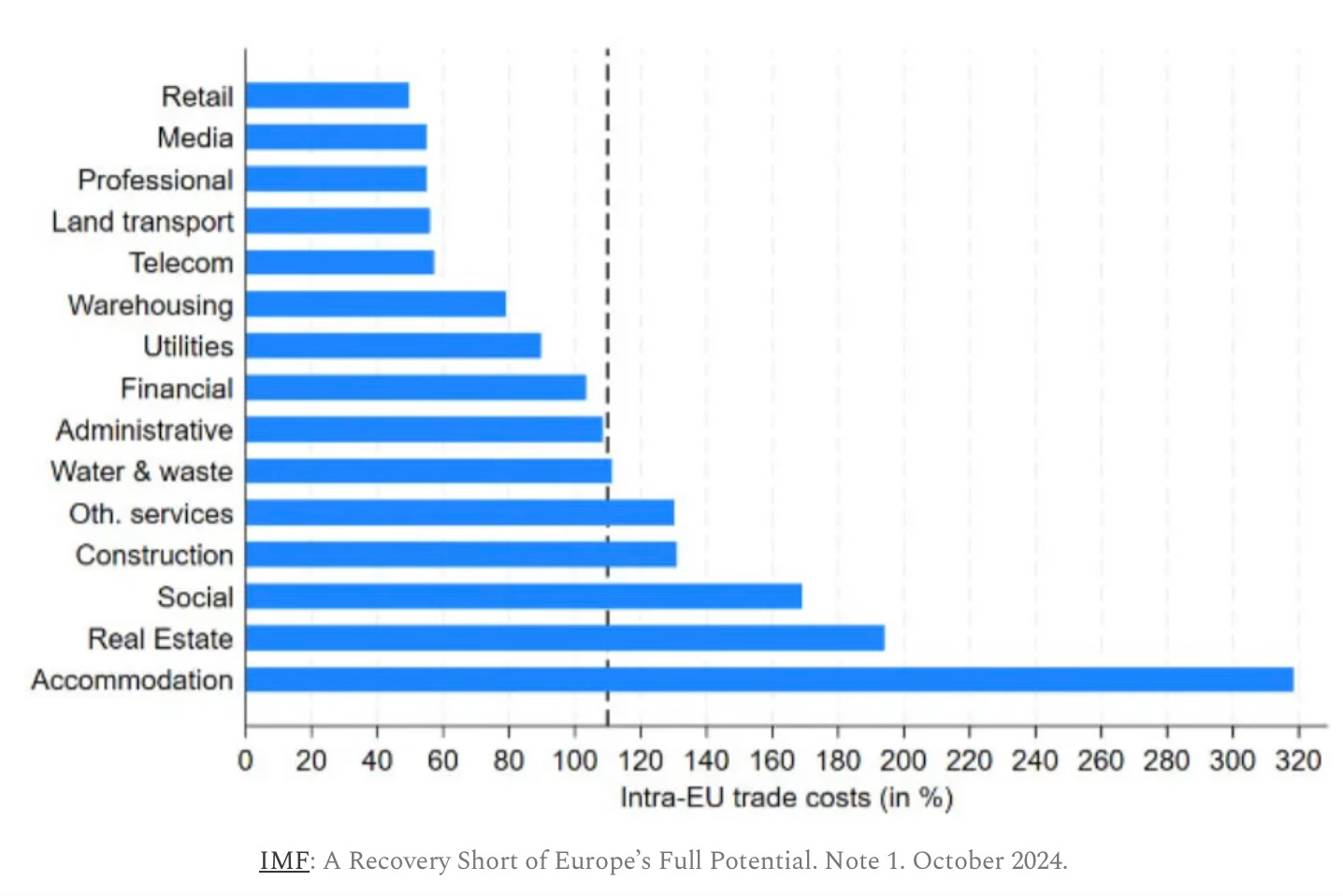

It also highlights the various types of non-tariff and other barriers affecting different goods and services sectors. The graphic below is the total tariff equivalent for various service sector segments.

Garciano points to the lack of harmonisation among EU member countries’ rules across sectors and the failure to adopt mutual recognition as a means to such harmonisation.

Tej Parikh has a good graphical summary of the importance of internal barriers as an economic friction.

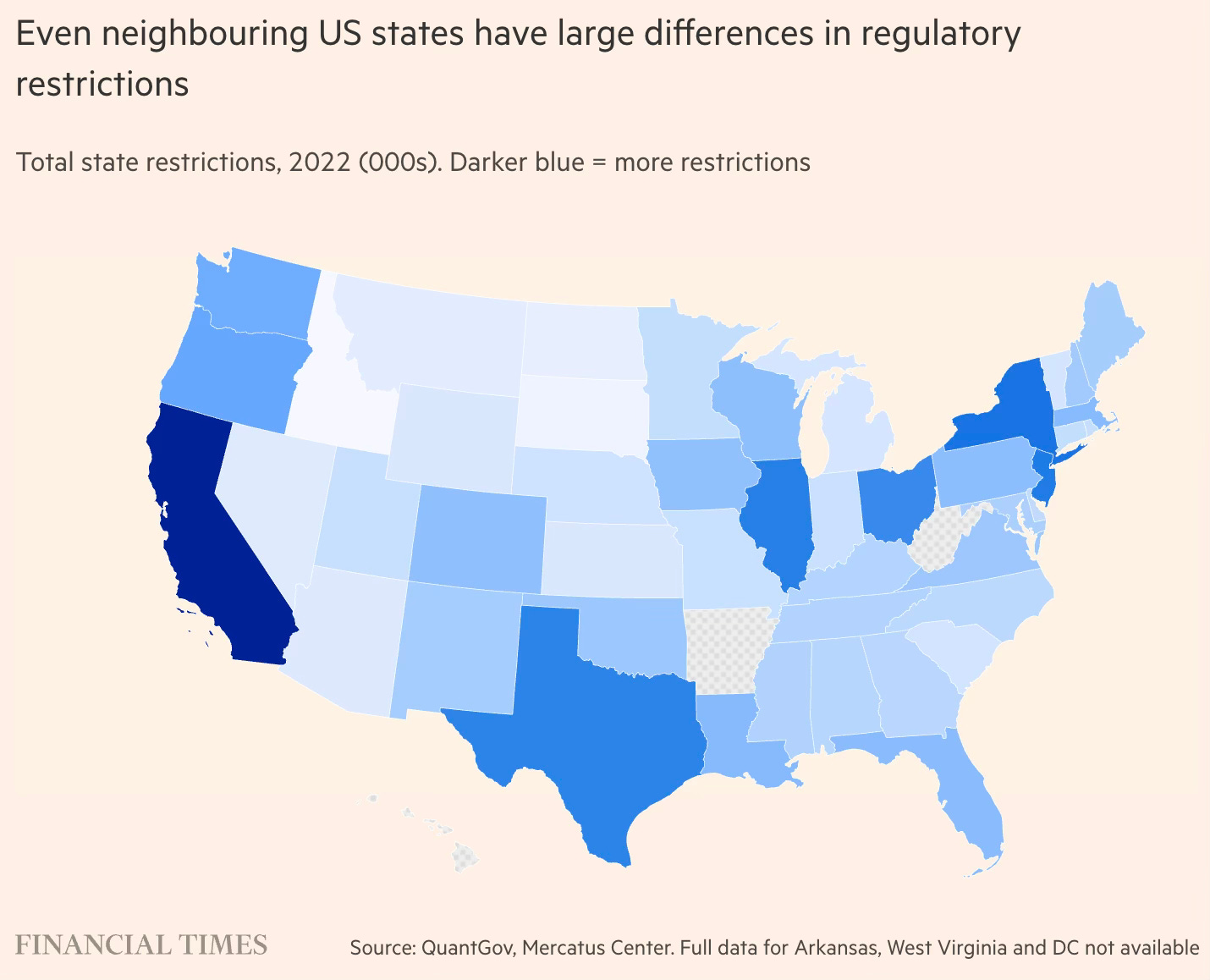

He points to a graphic from QuantGov that highlights the wide variations in regulatory restrictions across US states, arising especially in occupational licensing, tax disparities, and zoning laws.

Since the volume of internal freight flows in the US is about $20 trillion annually, even small improvements can have significant effects.

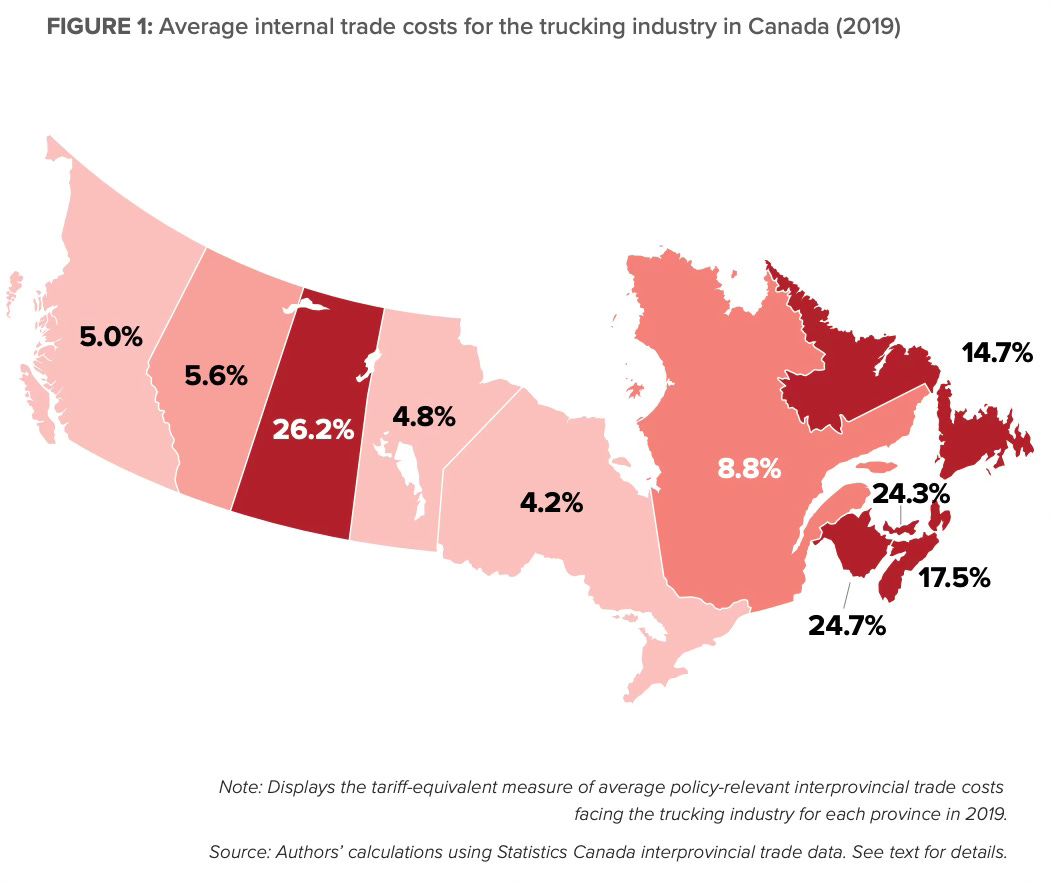

A striking reflection of internal barriers is that Canada trades more with the US than among its provinces!

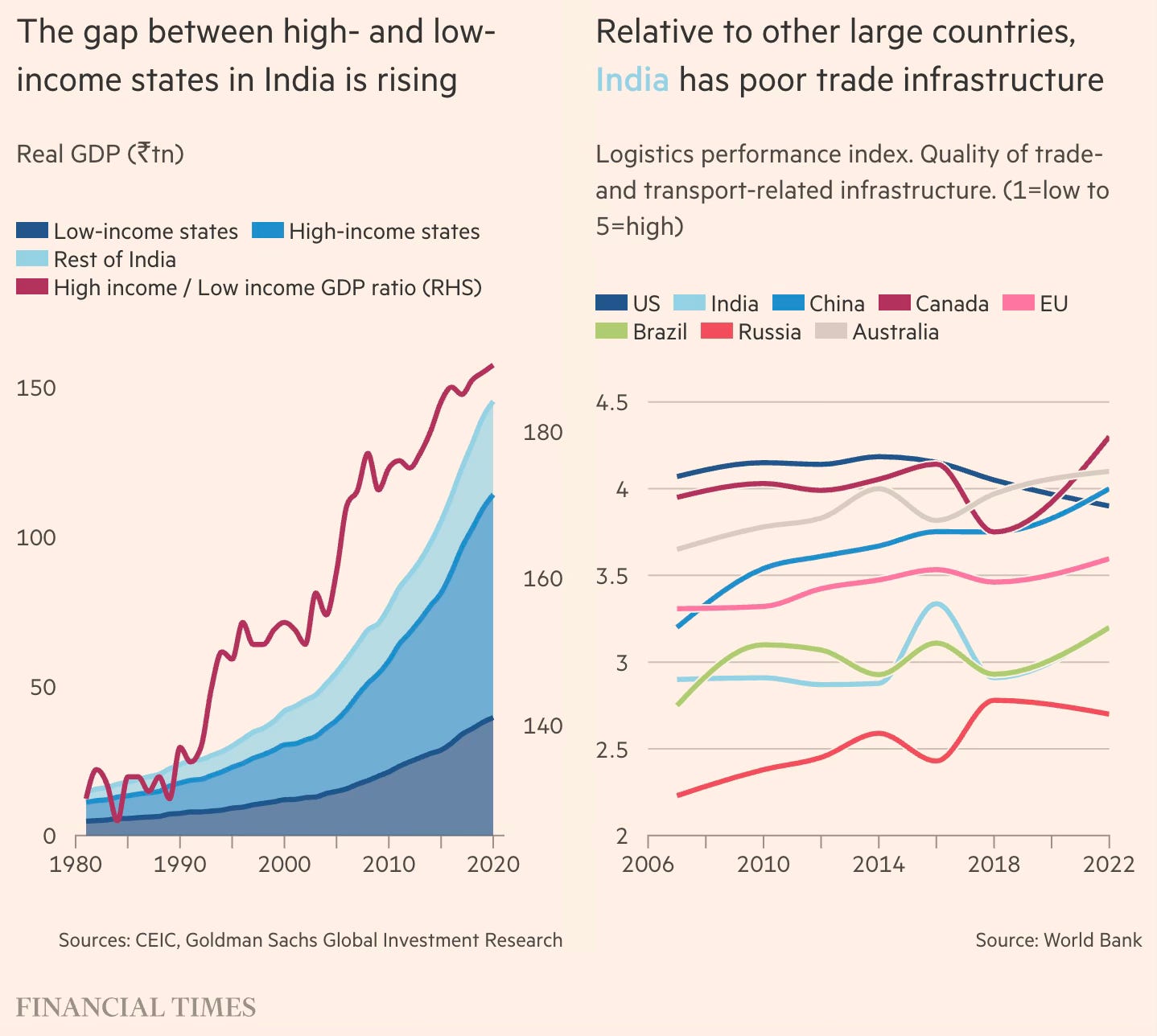

Such barriers contribute significantly to regional disparities, as in India.

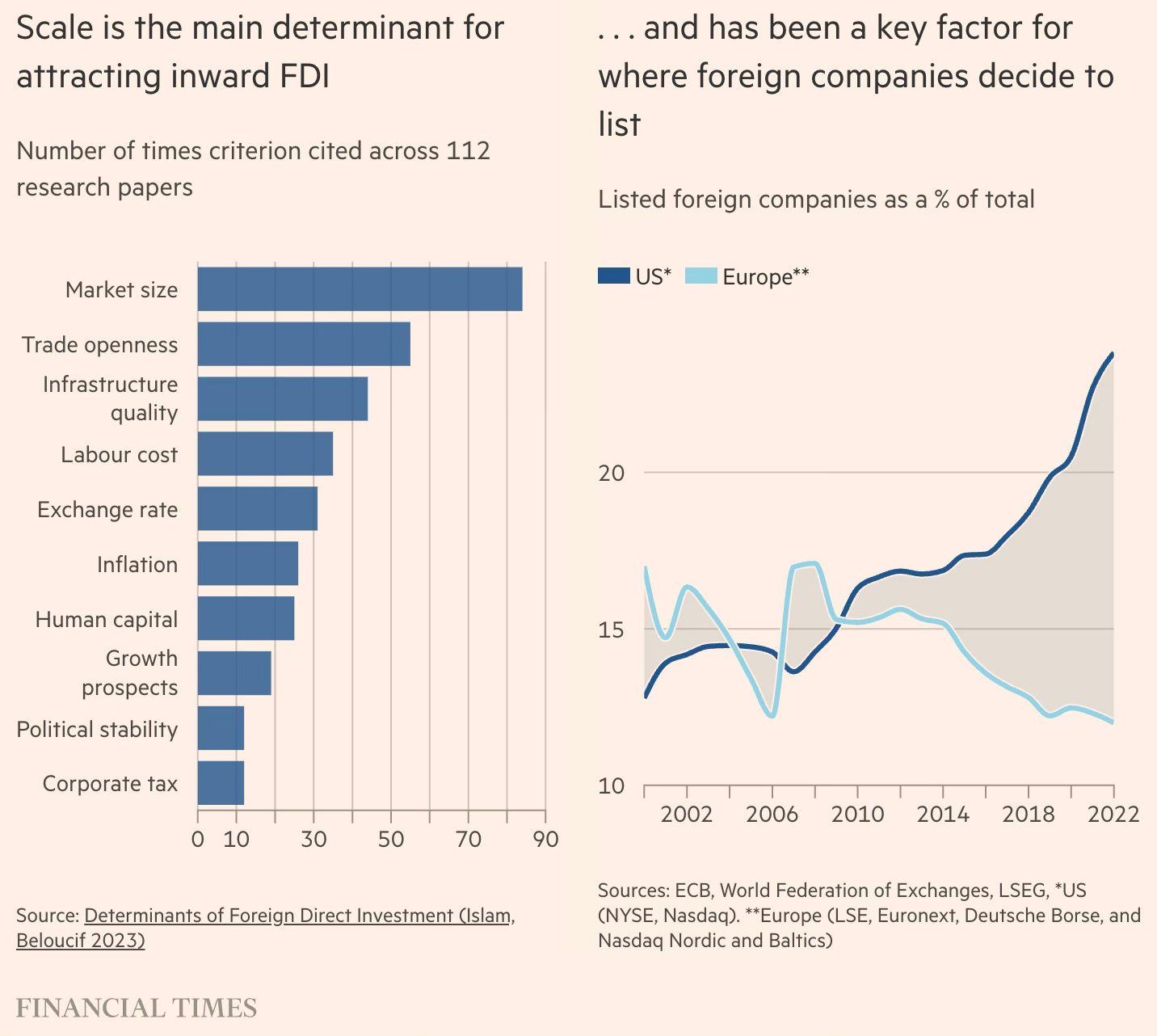

And they come in the way of integrating markets and realising scale, the major attractor for foreign investors.

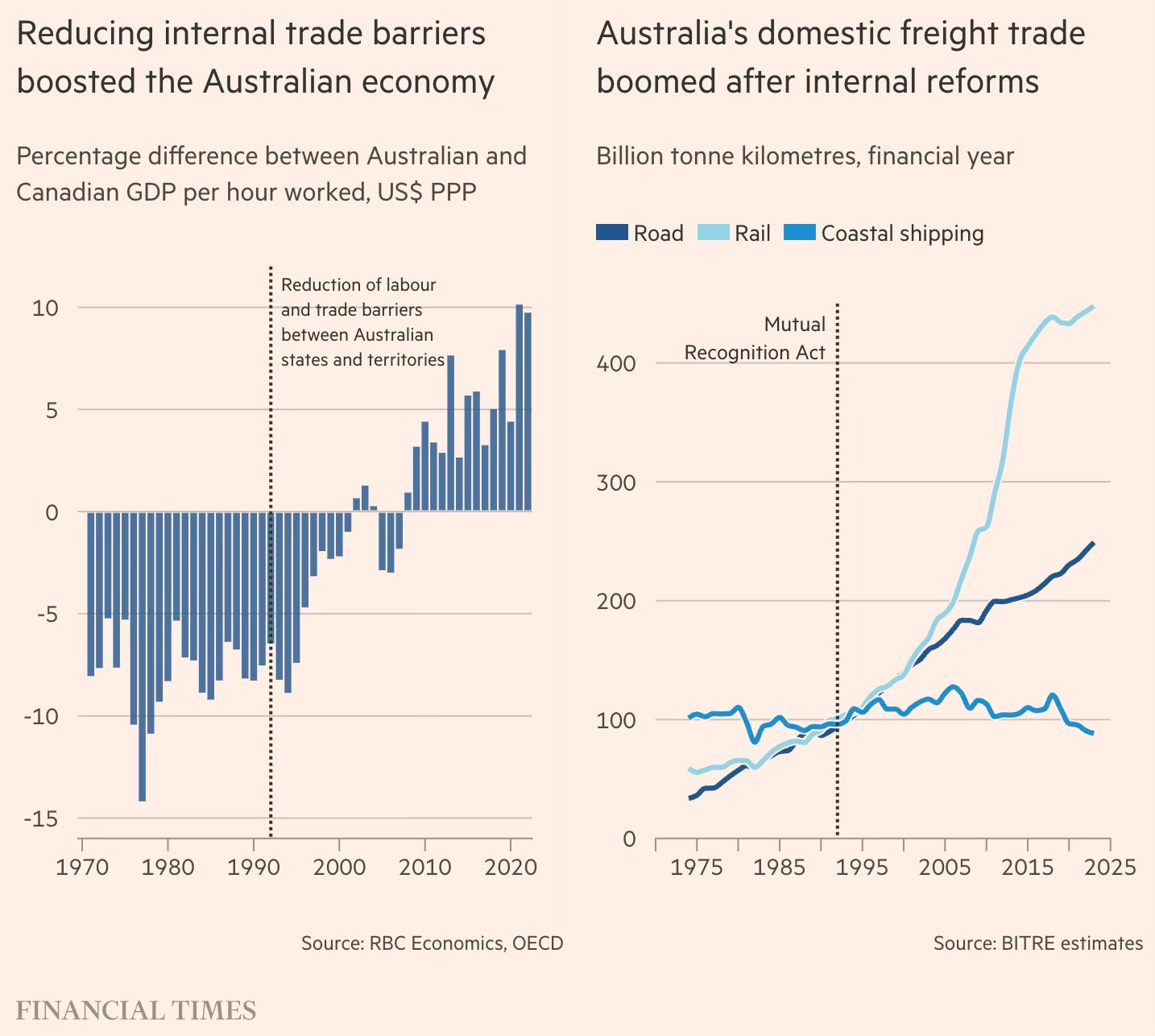

Fortunately, there are several examples from across the world on the impact of reforms to ease internal barriers. Australia’s Mutual Recognition Act in 1992 enabled goods sold in one state or territory to be sold in another without needing to meet further requirements, and also established equivalence in occupations. This contributed to increased domestic freight movement and productivity growth.

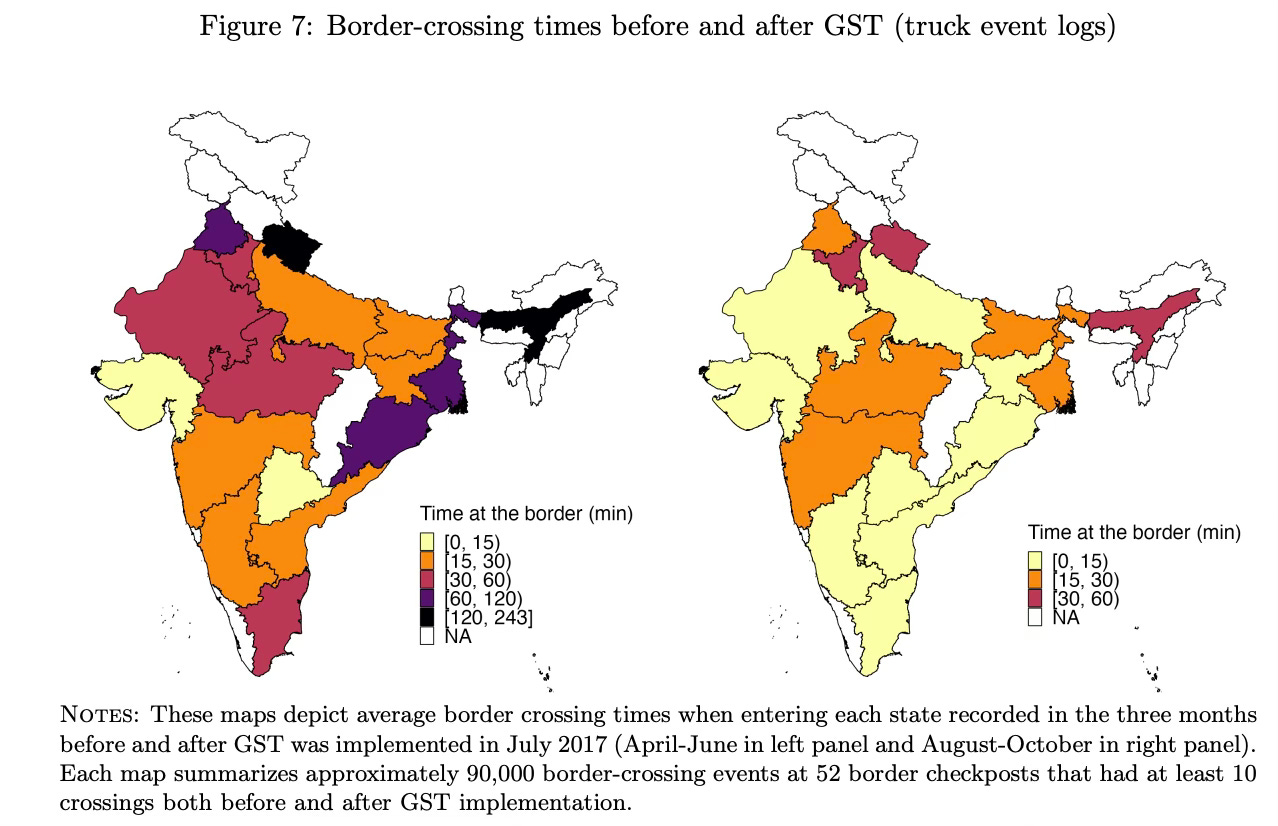

India’s GST led to the dismantling of border checkposts and dramatic reductions in border-crossing times across state borders.

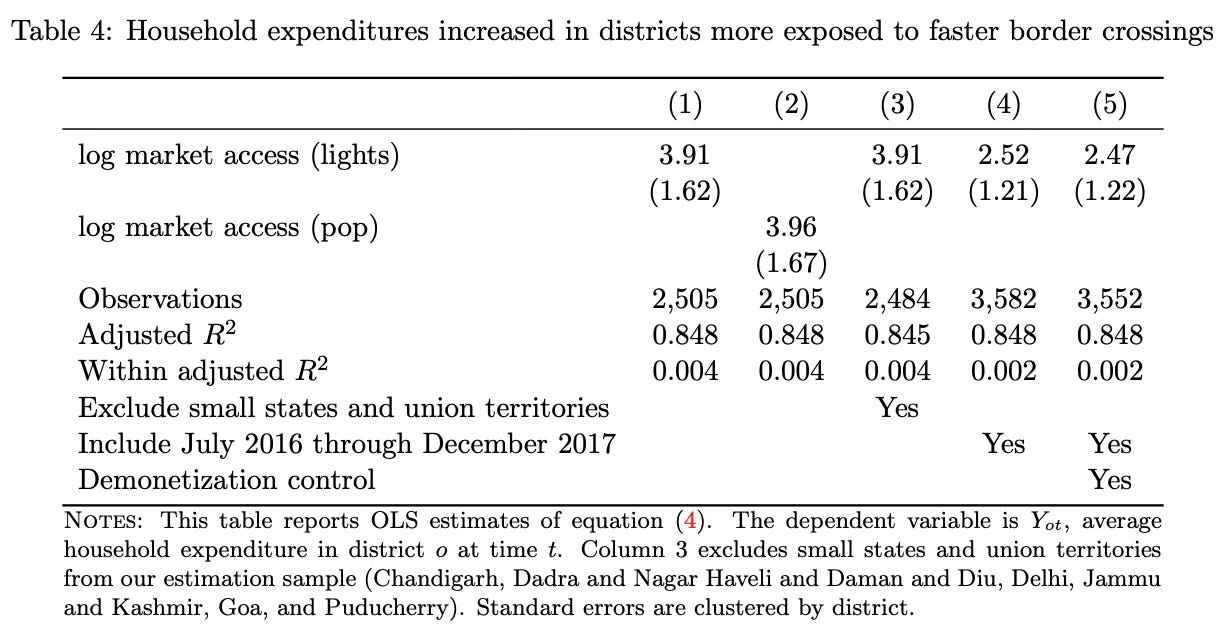

It also translated into increased household expenditures in districts more exposed to the faster border crossings. In fact, faster border crossings increased household expenditures by 2% to 23% across districts.

A Canadian study found that varying regulations faced by the truck transportation sector in the country added approximately 8.3% to freight rates.

Finally, in the context of removing internal barriers, Luis Garciano echoes the critical point that I blogged here, that deregulation in general should not be seen as a stroke-of-pen reform but as one that requires sustained engagement. He points to examples of how the implementation of deregulation often seriously detracts from achieving its objectives.

There are two problems: first, rather than replacing national regulations, EU rules pile on top of them. Second, member states often engage in ‘gold plating’ – adding extra national requirements when implementing EU directives. The result is that even when the EU does create common rules (directives or regulations aiming to harmonize), the outcome is often not a truly single market. New EU rules often don't replace old national ones. Instead, they create additional layers of regulation. A toy manufacturer might need to obey an EU toy safety directive while simultaneously navigating older national rules about specific materials… In a paper on capital market regulations in a top finance journal, Christiansen, Hail and Leuz (2016) find that, in fact, countries' rules diverge more (!) after harmonizing regulations…

In other words, the new rules often only serve to add new layers of legislation. For instance, the Single Supervisory Mechanism supervises the banks, but so do the national central banks who impose their own requirements of capital or liquidity on all banks operating in their territory. If a French bank operates in Belgium, it has to satisfy French, Belgian and European regulators. This reduces the synergies of operating across borders, and is the main reason our banking systems are, even today, mostly national. Or consider General Data Protection Regulation, which (in spite of being a regulation) still means we have regulators at EU, national and regional level…A publisher that trades across the EU must now keep separate analytics setups for Austria, France, and Italy, while the same tool remains legal elsewhere. The Draghi report notes that there are around 90 tech-focused laws and more than 270 regulators active in digital networks across all EU countries…

Despite EU directives aimed at facilitating the free movement of professionals, a specialized engineering company based in, say, Portugal, that wins a contract for a major infrastructure project in Germany might find that German authorities require their engineers to undergo a lengthy ‘equivalence check’ despite holding qualifications recognized under EU frameworks. For smaller firms or individual professionals, these hurdles can be prohibitive.

These problems echo across countries.

No comments:

Post a Comment