Amidst all the turmoil from the Trump shock, two regions widely perceived as perpetual laggards and accused of free-riding on the US security blanket - Europe and Japan - deserve greater attention. For a long time, both have been overshadowed by the dynamism and growth of the US economy. That might be changing, both due to America’s self-inflicted problems and them getting their acts together.

Europe gets a lot of bad press, especially compared to the US. Its fractured political union and tortuous decision-making process are matters of constant ridicule among commentators and media. I have always thought that it’s an unfair characterisation.

As a counterfactual, imagine making the same decisions in a federal country where both political and economic union is deeply institutionalised. In the absence of the kind of institutional powers that the governments of these countries enjoy, they would have found it very difficult to mobilise consensus among the warring political parties and federal constituents.

Further, notwithstanding their squabbles, the strong unity of purpose and rapid mobilisation of resources in the aftermath of the Russian invasion of Ukraine shows that Europe tends to get its act together when it matters. Finally, the comparison with the US is unfair not only because the US is a sovereign country but also because of the US’s unmatched economic dynamism and exceptionalism.

True, there are aspects of European politics and economics that are matters of debate. The European economy could do with more dynamism and entrepreneurship. It could deregulate and prune down its excessively generous welfare state. It could invest more in its defence and project its soft and hard power to play an active role as a global hegemon. It could avoid free-riding on Russian energy sources and the Chinese market and their manufacturers while oblivious to and externalising their strategic costs. It could also calibrate towards a more balanced trajectory on immigration and climate change.

But these European trends also have had their merits. European governments have been the undoubted trendsetters on climate change mitigation, and at an ambitious pace at that. European regulators have taken the lead on competition and anti-trust with several bold and path-breaking decisions. The conservatism or perceived lack of dynamism among European firms and financial institutions also reflects a reluctance for the unqualified embrace of the short-sighted shareholder wealth and efficiency maximising American corporate culture. Europeans must retain all these desirable features while striving for a balance in their policies.

In any case, the important development is that, caught on the wrong foot from the decisions in Washington, Europe appears to be coming together and responding in one voice. President Trump has shocked and awed the Europeans with his whimsical tariffs, embrace of Russia, support for far-right parties, and withdrawal of the post-war security blanket.

America’s embrace of Russia has also led to a remarkable about-face between the UK and EU as they started talks to set up a Europe-wide shared defence funding structure. The new-found leadership of the British Prime Minister in rapproachment with Europe and standing up to Russia has been praised as Winston Starmer!

The external threat, perhaps even existential, appears to have been the right stimulus for Europeans to galvanise and bite the bullet on several long-delayed reforms. Gideon Rachman has even written that “Trump is making Europe great again”.

A poll last week showed that 78 per cent of British people regard Trump as a threat to the UK. Some 74 per cent of Germans and 69 per cent of the French agree. In another poll, France was rated as a “reliable partner” by 85 per cent of Germans and Britain scored 78 per cent — the US is down at 16 per cent… The Europeans can see how much trouble the Ukrainians are in after the Trump administration’s decision to cut off flows of intelligence and weaponry. So they are pursuing a two-track policy. They need to delay the severance of American military support to Europe for as long as possible, while preparing for that moment as fast as possible.

A landmark reform may be the dissolution of the last resistance to the issuance of common European debt. The first blow in this direction came in the aftermath of the pandemic to issue common debt to fund the post-pandemic recovery. But that was considered an exception in response to an extraordinary event. The latest decision to allow the European Commission to raise €150 bn to spend on the EU defence industry may be a more seminal shift. As Rachman writes, it has implications that go beyond raising money for defence.

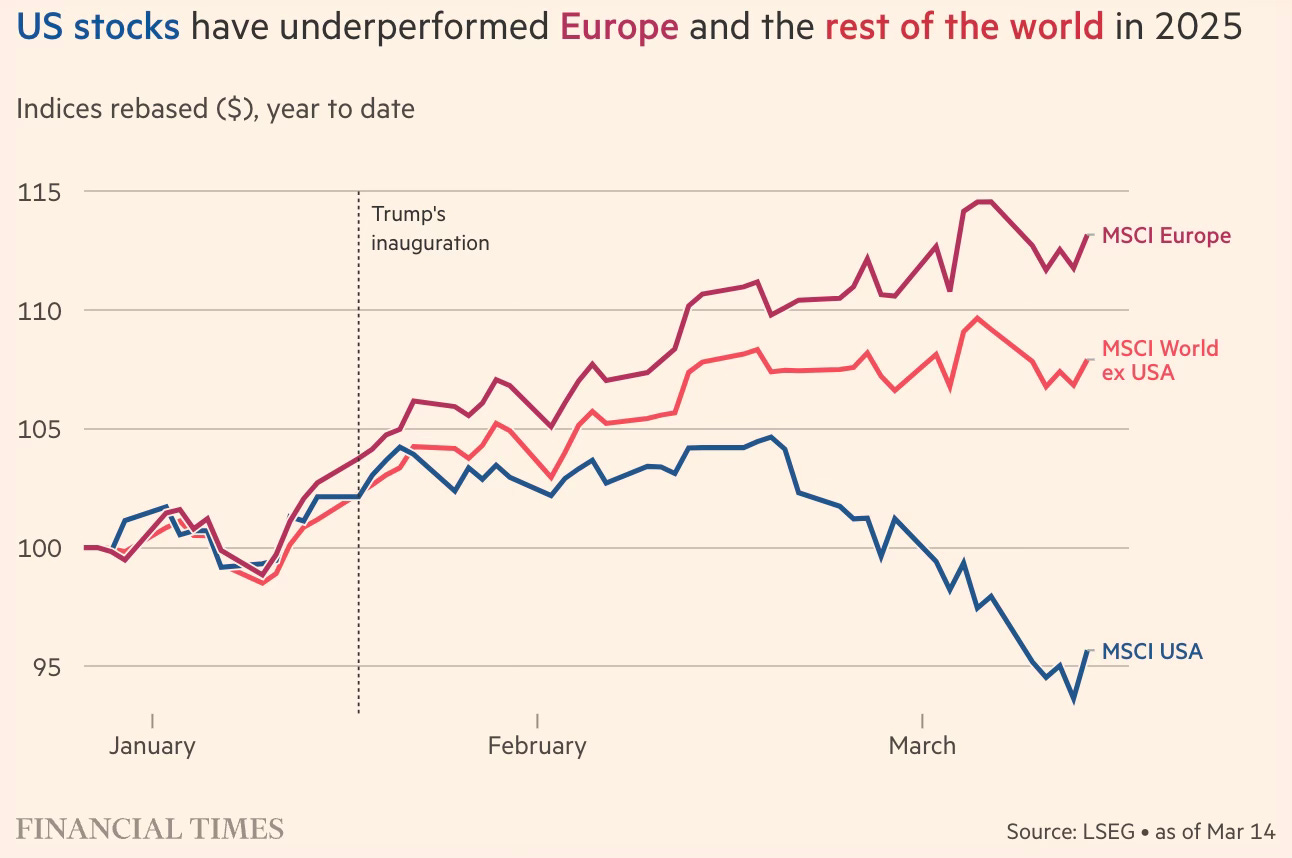

It also offers the chance to build up the euro as an alternative to the dollar as a global reserve currency. The capriciousness of the Trump administration means that there is a considerable global appetite for an alternative to US Treasuries as a safe asset…Trump’s final favour to Europe is to hasten the post-Brexit rapprochement between the EU and the UK. Sir Keir Starmer and Emmanuel Macron, the British and French leaders, have worked together closely on Ukraine. They could form a powerful triumvirate with Merz… The prospect of repairing some of the damage done by Brexit underlines that this is not just a moment of threat for Europe. It is also a moment of opportunity. Europe can now plausibly offer a more stable business environment than Trump’s America — which may already be reflected in the relative performance of stock markets in the US and Europe. As the Trump administration increases its assault on US universities, there is also a chance to attract leading researchers to Europe. The gap in salaries and research money between North America and Europe is large. But the overall sums of money involved are small, when compared with the amounts being thrown around for defence.

He also points to lessons from history about Europe’s resilience when faced with adversities.

There will be plenty of disagreements and setbacks on the way to greater European unity. France and Germany are already clashing over how the new EU defence fund will spend its money. Every clash like that will feed the scepticism of those who say that Europe will never get its act together. There were similar doubts and setbacks on the often bumpy road to setting up the original European coal and steel community in the 1950s and the single currency in the 1990s. But European leaders got there in the end because the political imperative to agree was so overwhelming. All of the great leaps forward for European unity have been caused by geopolitical shocks — first the end of the second world war; then the end of the cold war. Now, courtesy of Trump, we are looking at the end of the transatlantic alliance. Europe responded with strength and inventiveness to the last two great challenges. It can do so again.

Martin Wolf echoes Rachman

Since the 1970s the US has suffered a moral collapse from which it is unlikely to recover. We see this daily in what this administration is being allowed to do to US commitments, to allies, to the weak, to the press and to the law… Maga attitudes are close to those of today’s Russians: power will not be yielded easily. This is a truly historic catastrophe. But if the US is no longer a proponent and defender of liberal democracy, the only force potentially strong enough to fill the gap is Europe. If Europeans are to succeed with this heavy task, they must begin by securing their home. Their ability to do so will depend in turn on resources, time, will and cohesion.

Wolf also points to the challenge of a sharp and rapid break from the US in its security and defence strategies.

Its economic potential cannot be turned into strategic independence from the US overnight. As the London-based International Institute for Strategic Studies shows, European weaponry is too dependent on US products and technology for that to be possible. It will need a second and scarcer ingredient — time. This creates a vulnerability shown, most recently, by the feared impact of the cessation of US military support for Ukraine. Europe will struggle to supply what will be missing.

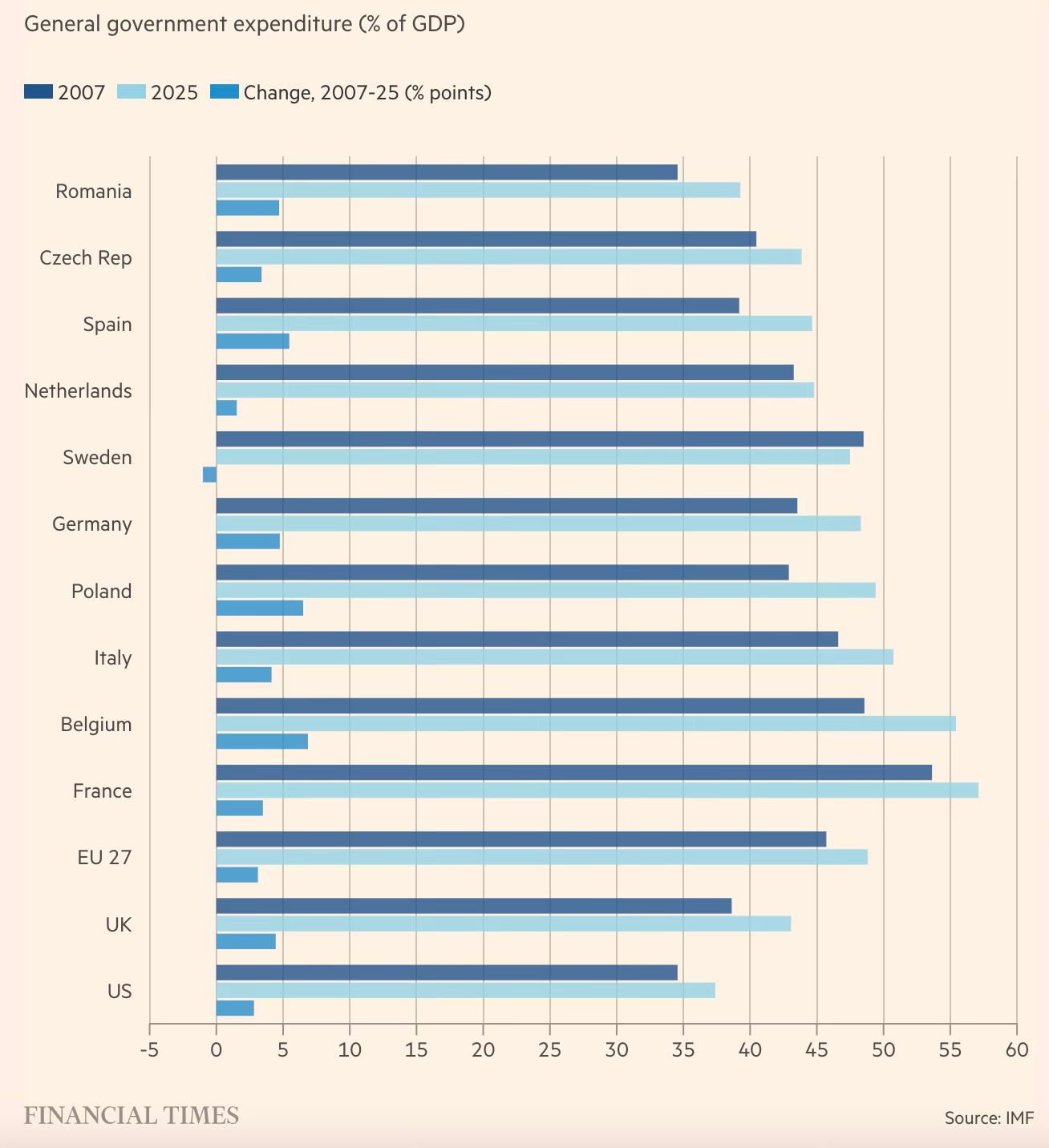

Europeans must scale down their excessive public spending and redirect some of it towards defence.

Fortunately, lower fiscal deficits and net debt-to-GDP ratios compared to the US mean that Europeans have the fiscal space to substantially increase their defence spending from its current low level of 1.9% of GDP.

Another example of the European shift is in climate change. There has been a subtle shift away from rapid decarbonization towards a more prudent strategy to prevent deindustrialisation. The clean industrial deal to support some of Europe’s biggest polluters while sticking to the EU’s green targets and the dilution of new emission rules for internal combustion engine cars are examples.

Scott Galloway has a very good blog where he argues passionately for Europeans to get their act together and take the lead in defending liberal democracy. Fortunately, the timely Draghi Report that looked at the challenges of competitiveness and dynamism faced by European companies has clear diagnosis and concrete recommendations on restoring Europe’s economic prospects.

Nowhere in Europe has the Trump shock found stronger introspection than in Germany. The incoming coalition there under Friedrich Merz has stressed “independence” from the US and signalled its resolve to move ahead economically and militarily without the US. He has sought a paradigm redefining shift from Germany’s traditionally tight fiscal conservatism and committed to do “whatever it takes” to invest in infrastructure and defence and stimulate the economy.

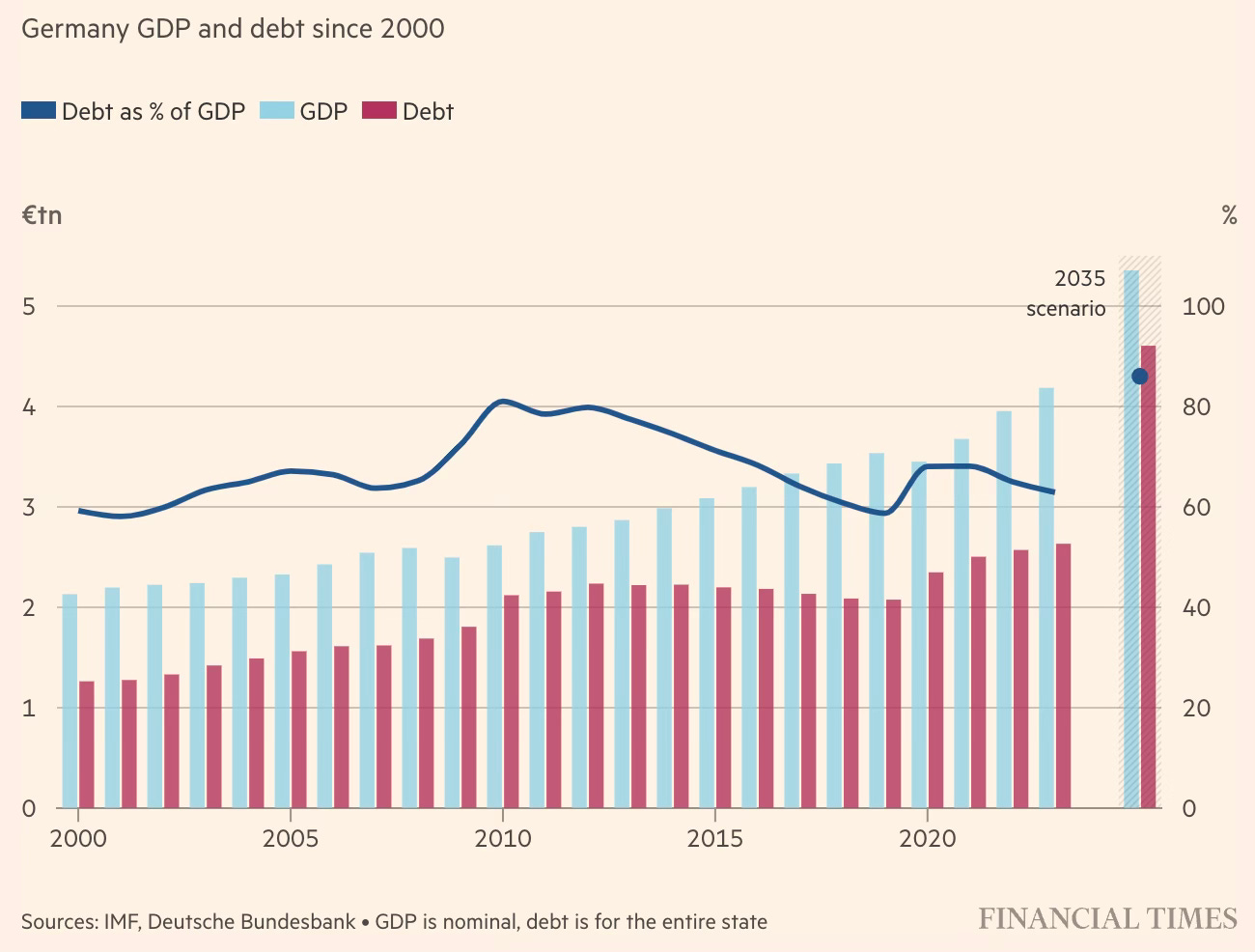

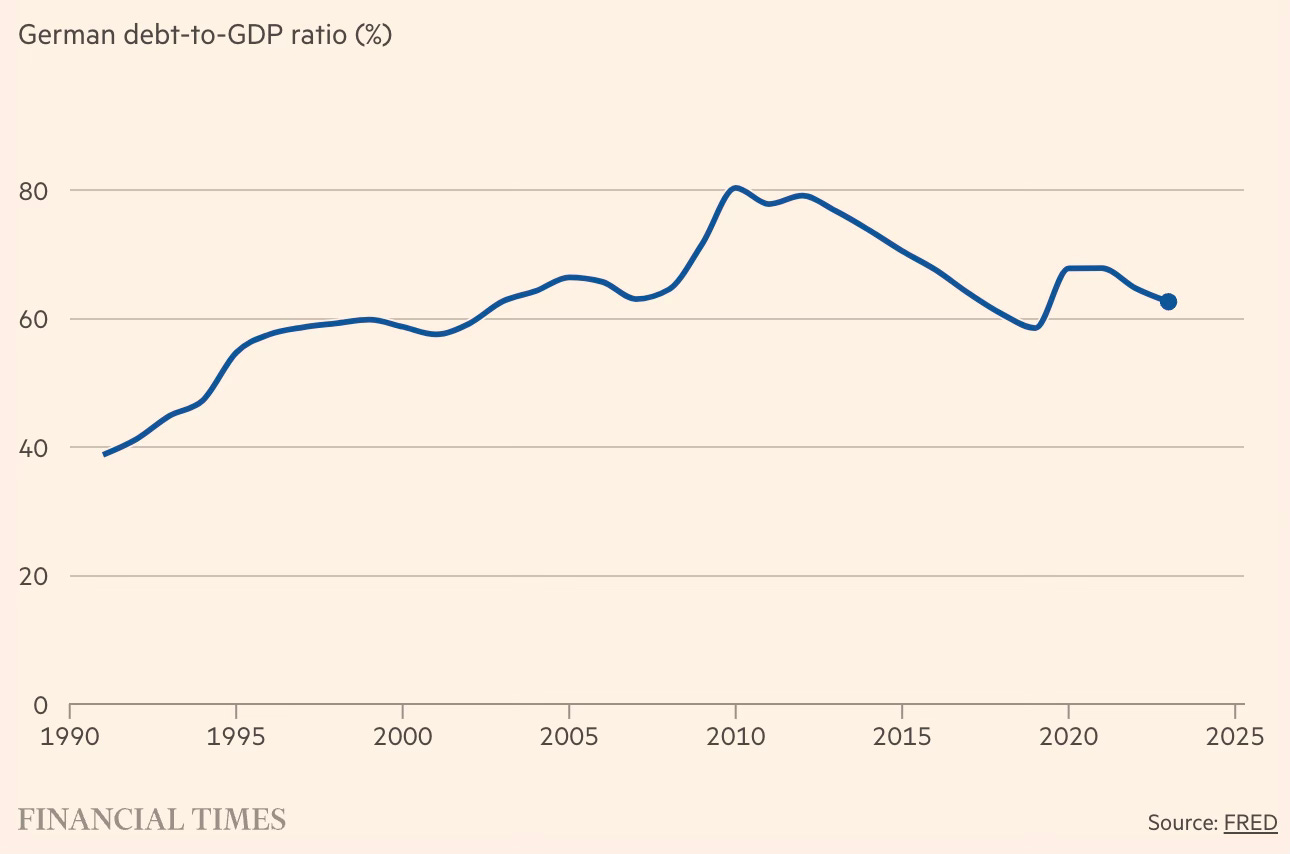

The proposed scheme is reminiscent of the efforts after reunification and allows for potentially unlimited borrowing for defence spending and the creation of a €500bn 10-year fund to drive infrastructure investments. The plan is expected to provide up to €1tn of additional borrowing over the next decade, more than a fifth of the country’s output. The plan requires a two-third supermajority support for the relaxation of the “debt brake” written into the German constitution in 2009 that limited the government’s incremental borrowing to a very stringent 0.35% of GDP. It would do this by enabling the exclusion of everything over 1% of GDP spent on defence.

Goldman Sachs anticipates that the plan could drive German defence spending to as much as 3.5 per cent of GDP by 2027 — up from 2.1 per cent in 2024 and a mere 1.5 per cent in earlier years, according to Nato numbers. The FT calculationsof the €1.9tn in fiscal space assume that German nominal GDP will increase by 2 per cent per year from €4.3tn to €5.4tn by 2035. This estimate is likely to be conservative, as it does not account for any real GDP growth, should inflation match the European Central Bank’s 2 per cent target. Others too have estimated an atleast 2 per cent growth trend with the stimulus spending.

The markets reacted to the announcement with the yield on the 10-year Bund surging 0.31 percentage points to 2.79 per cent, its biggest one-day move since 1997. Fortunately, instead of being alarmed, this should be seen as a strong signal of endorsement of the decision from the markets and a vote of confidence in Germany’s economic prospects. Accordingly, the Dax surged, and the shares of German defence and infrastructure companies have been rising.

The country’s debt-to-GDP is expected to rise from 63% to 84%, far lower than the levels in other major developed economies. Further, this mirrors the post-reunification rise in borrowing, when the debt share of GDP doubled in two decades, and from 41% to 60% in just five years.

Some infrastructure projects, such as a €53bn investment plan for Germany’s creaking railway infrastructure between 2025 and 2027 that was fleshed out late last year, are largely “shovel-ready”, providing the potential to more or less immediately lift growth.

Underlining the growing promise about Europe’s economy, its stock markets have been the standout performers in 2025. German Dax has led the way.

This brings us to the second region where things are looking up. The Japanese economy is often held out as a portend on many macroeconomic problems - stock market stagnation, zero interest rates, deflation, weak currency, high debt, declining workforce, zombie companies etc. There are signs that the country has managed to overcome all these and may be becoming a more normal economy.

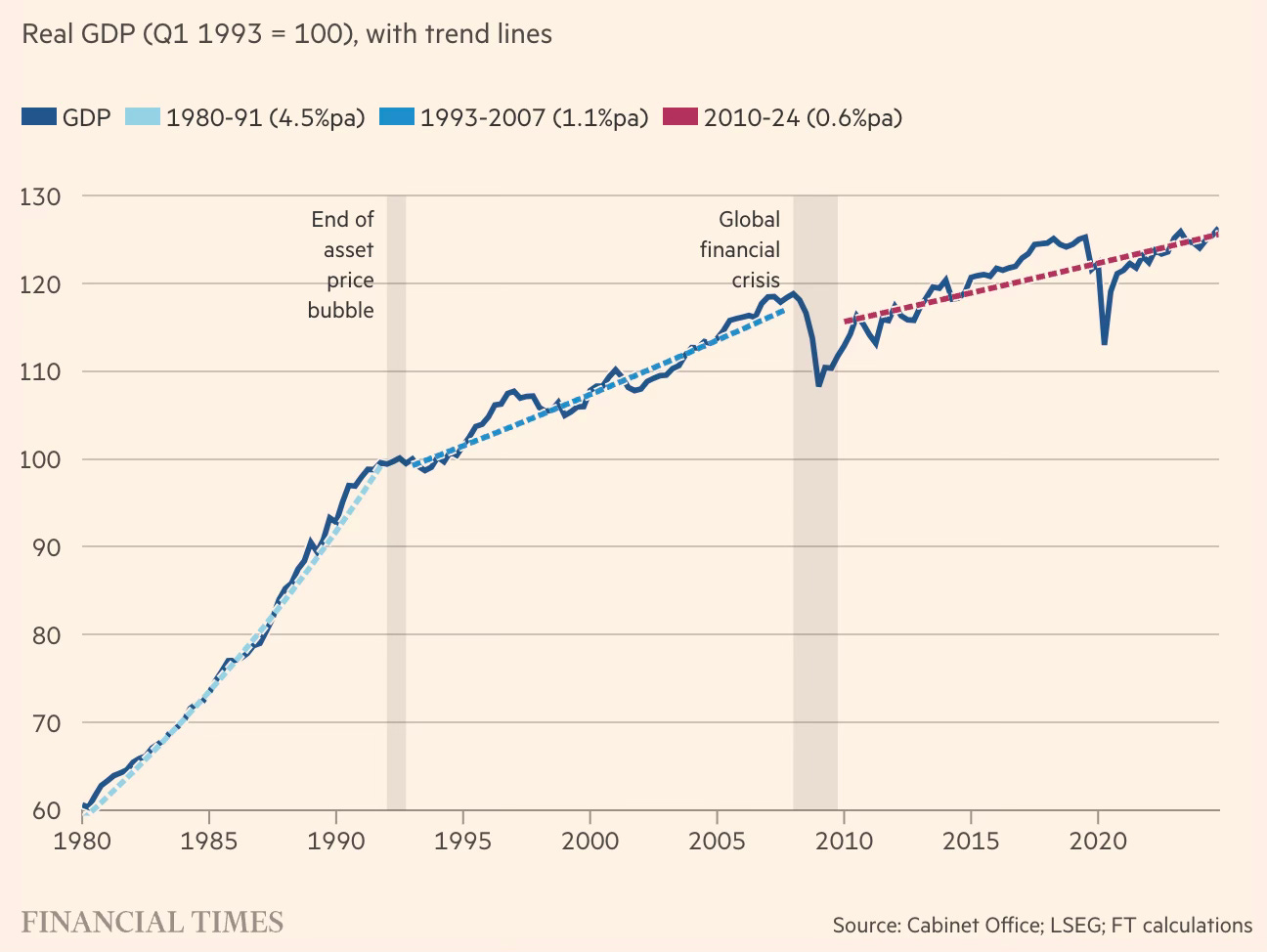

The FT has an excellent graphic that captures the country’s economic trajectory since 1980, in particular pointing to a possible “lost decade” since 2010.

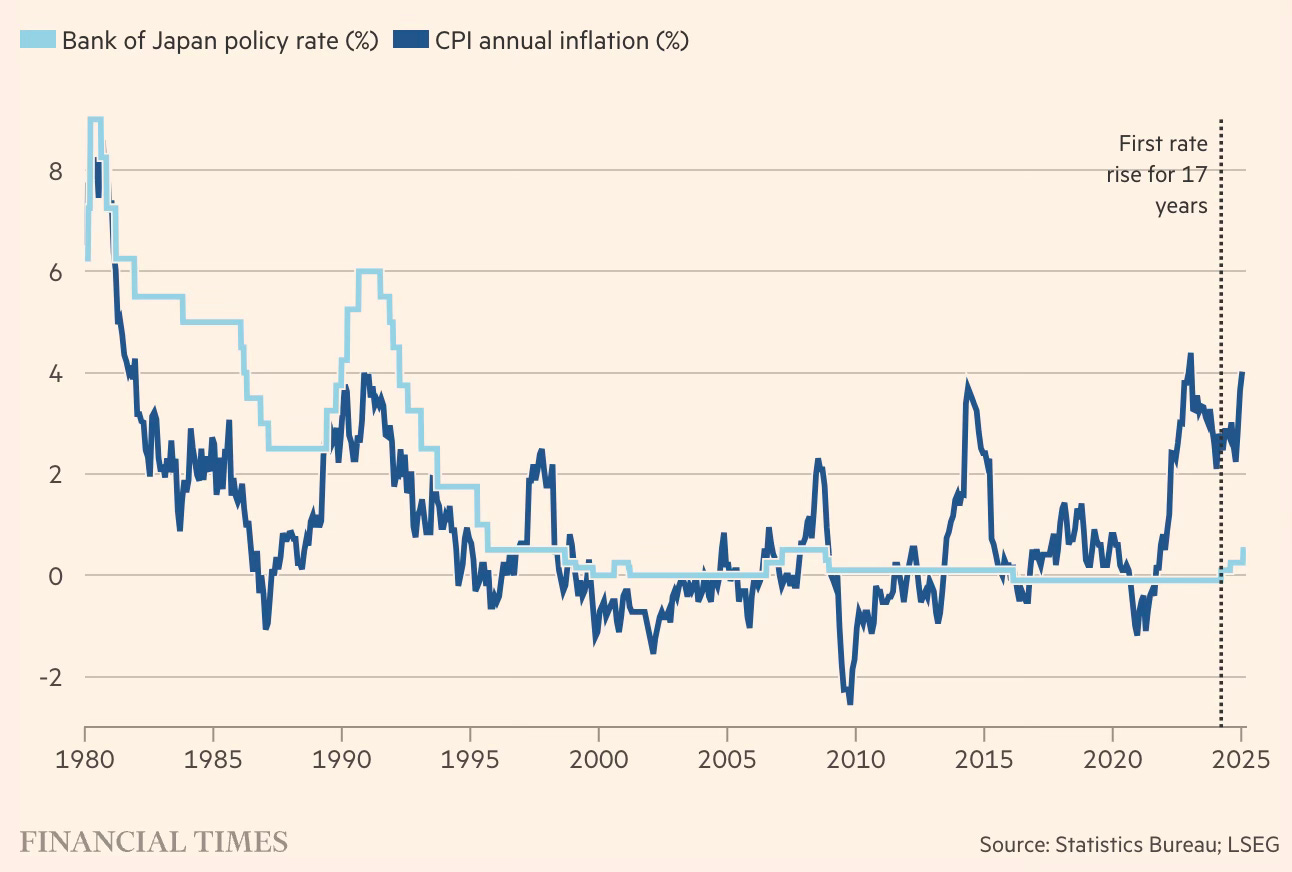

For a long time, Japan did everything possible, including an extended period of BoJ keeping rates below the zero bound, to bring back inflation. Finally, inflation is back. It's a different matter that while it has got inflation, its consumers don't appear to be liking it! BoJ's policy rate, which has never gone beyond 0.5%, looks set to rise.

In January, core inflation reached 3.2%, well past the BoJ's target rate of 2%, and nominal wages have been rising (also due to a shrinking workforce), and headline pay rise hit a multidecade high last year.

Japan’s great inflection is happening under an extraordinary confluence of pressures. Geopolitics have pushed up prices of energy as well as food, both of which Japan imports in abundance. The yen, partly because of the Japanese corporate and institutional tendency to invest abroad, has been weak for an extended period. And the rate of population shrinkage in the country is approaching an average of two people every minute, reordering the way business thinks long term about labour supply and a historic duty to keep unemployment low... More broadly, the consequences of a Trump-induced global tariff war, potential episodes of severe currency volatility and the threat of economic downturn in the US are adding uncertainty.

But amidst all these headwinds, the return of inflation offers tantalising possibilities for a country where massive amounts of household savings are sub-optimally kept in low-return fixed-income assets. In most contexts, rising inflation and interest rates come with concerns of weakening economic growth and recession. But in the case of Japan and Germany, they might be different and even welcome.

Even if late, the BoJ may have to be credited with a successful strategy to transition expectations from a deflationary era.

The impact on Japanese households is of keen concern to everyone, notably the government and central bank — and here again there are complexities... In preparing for normalisation... the BoJ purposefully positioned itself behind the curve. It allowed two full years for both headline and core inflation to approach its target before taking action, in the hope that households would have time to adjust. There are some indications that the policy has worked. Although price rises have forced many companies to raise wages, there was a delay during which households were unable to save as much as they did during deflation. And just as people realised they needed greater returns on their savings to survive, asset values — including domestic and US stocks — were rising. “That helped reintroduce the concept of a time value of money,” says Fink, highlighting not only the loss of purchasing power from holding zero-interest rate savings, but also the opportunity cost of failing to take advantage of positive yields. Online banks are vying to poach customers from traditional banks by plastering adverts for savings accounts with 0.4 per cent everywhere — tiny compared to many other countries, but a huge change for Japanese people.

Given the massive amounts of household savings sub-optimally kept in low return fixed-income assets, the rise of interest rates bodes well for the financial markets.

Meanwhile, the asset management industry is licking its lips at the prospect that at least some of Japan’s roughly $7.4tn stash of cash savings will be funnelled towards mutual funds and other investment products. In January 2024, with superbly judged timing, the Japanese government dramatically expanded the allowable limit of the Nisa tax-protected saving scheme, which is modelled on the UK’s individual savings account (Isa). Japan’s household asset weightings to equities and investment trusts now stand at 20 per cent, according to BoJ data. Though still distant from the 50 per cent in US and 30 per cent in Europe, this level is roughly double what it was a decade ago. Net purchases of Japanese equities by households and domestic investment trusts since the Nisa expansion have exceeded ¥1tn ($6.8bn), according to Nomura.

And there are promising signs that corporate Japan in general may be waking up from its long slumber and shedding its zombies.

After the Abenomics years, when companies were comfortable with their balance sheets and the corporate sector was a net saver, many companies are now in the process of jettisoning non-core assets such as huge real estate portfolios, businesses that have no real link with their main operations and vanity projects like art galleries. The government is clearly supportive of consolidation, and is not standing in the way of shareholder pressure for reform. After a spate of mergers, delistings and take-privates, 2024 was the first year that the number of listed companies on the main Tokyo exchange fell slightly — a modest contraction, but one that analysts predict will now unleash a much faster corporate metabolism. Bankruptcies are picking up; zombie companies are now more vulnerable to collapse. There is a genuine possibility, say analysts, that Japan’s squeamishness about creative destruction will become a thing of the past... In an attempt to deploy their capital more effectively, companies in the retail, hospitality and manufacturing industries are investing to raise productivity, particularly in long-overdue IT upgrades.

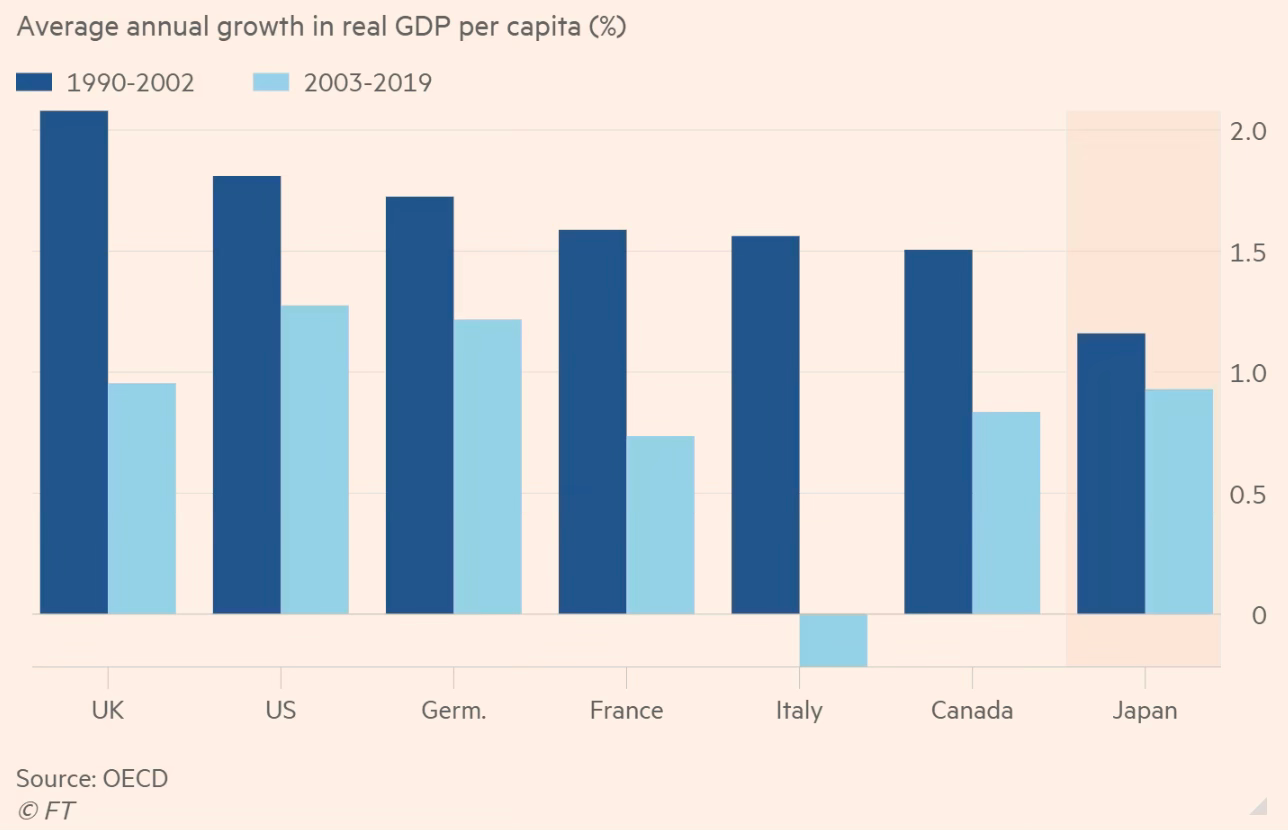

It may be a mistake to equate Japan’s three-decade-long period of low GDP growth rate with an erosion of economic competitiveness. As Adam Posen has written, while Japan had the lowest average per capita GDP growth rate among G7 economies in 1990-2002, in the period from 2003-19 it had the third highest per capita GDP growth rate and the second highest productivity growth rate.

Japan may well have the last laugh

Japan may in the end come out back on top in its economic peer group for the next decade, having done a better job on public health management than the EU or US, and having seen the smallest decline in its productivity growth rate since 2003.

No comments:

Post a Comment