I blogged here arguing, among other things, that collecting tax and non-tax arrears is a very challenging endeavour. Central and state tax agencies have large amounts locked up in such arrears, including litigation. Only a tiny proportion of these amounts is ever realised.

Arrears refer to any amount due from the taxpayer due to confirmation of demands due to original orders, appeals, and tribunal/court orders. They are in turn classified as recoverable and irrecoverable (those where there are court stay orders). Let’s take a look at the magnitude of these arrears of the central government’s direct and indirect tax departments.

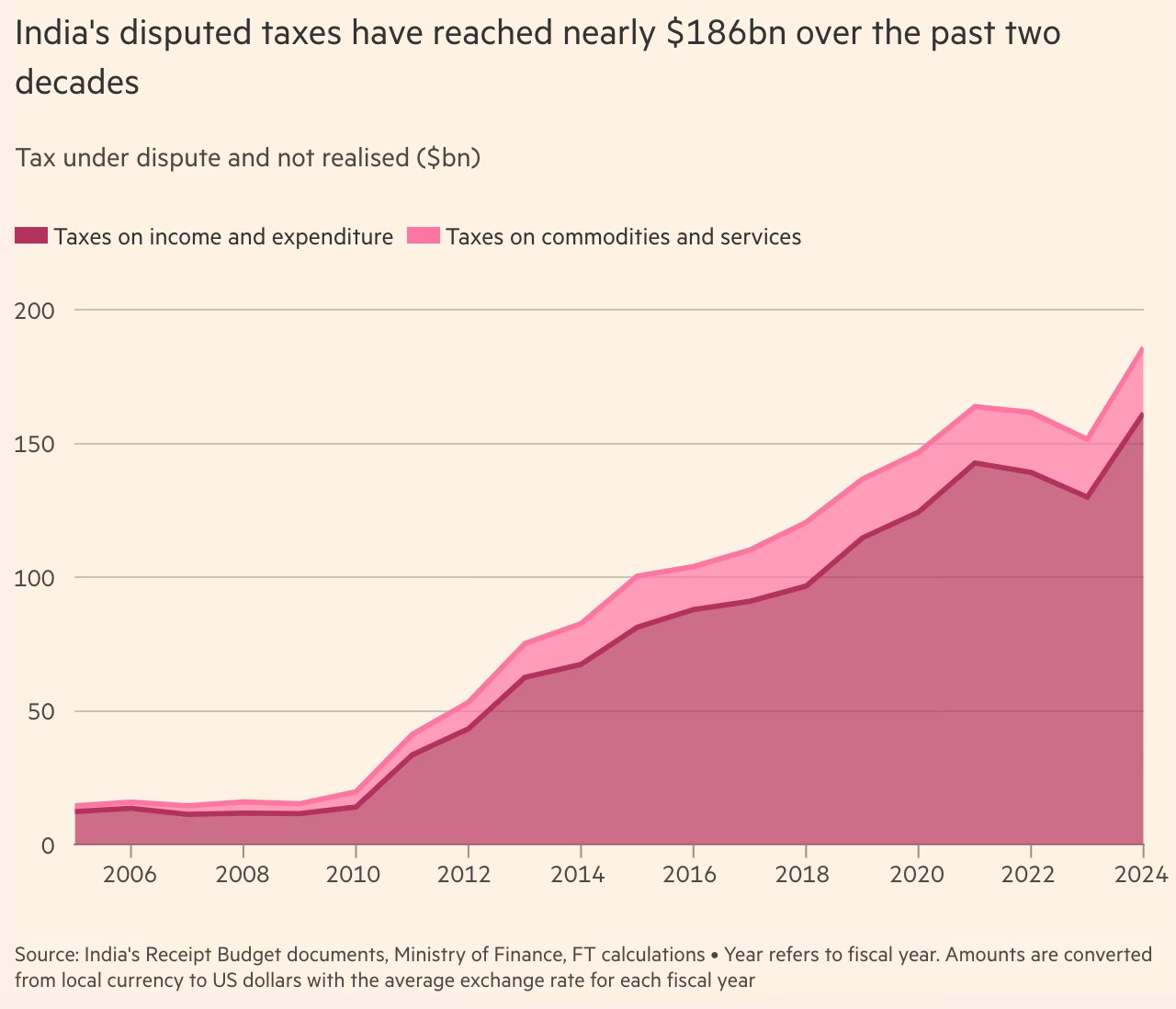

The FT has a good graphic that informs that disputed tax arrears amount to $186 bn, rising a staggering 1140% from $15 bn in 2010 to $186 bn in 2024.

This is the story of the $1.4 bn tax demand raised on Volkswagen in September 2024 on what appears to be a case of legitimate tax minimisation to skirt around a clear loophole in the tax structure.

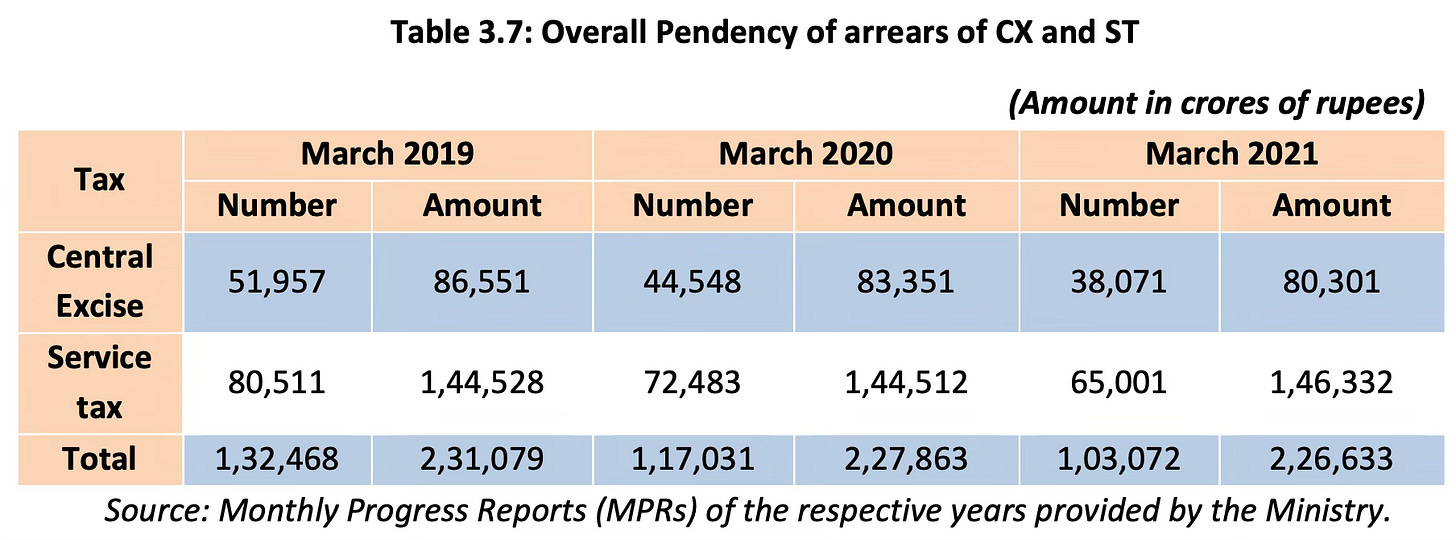

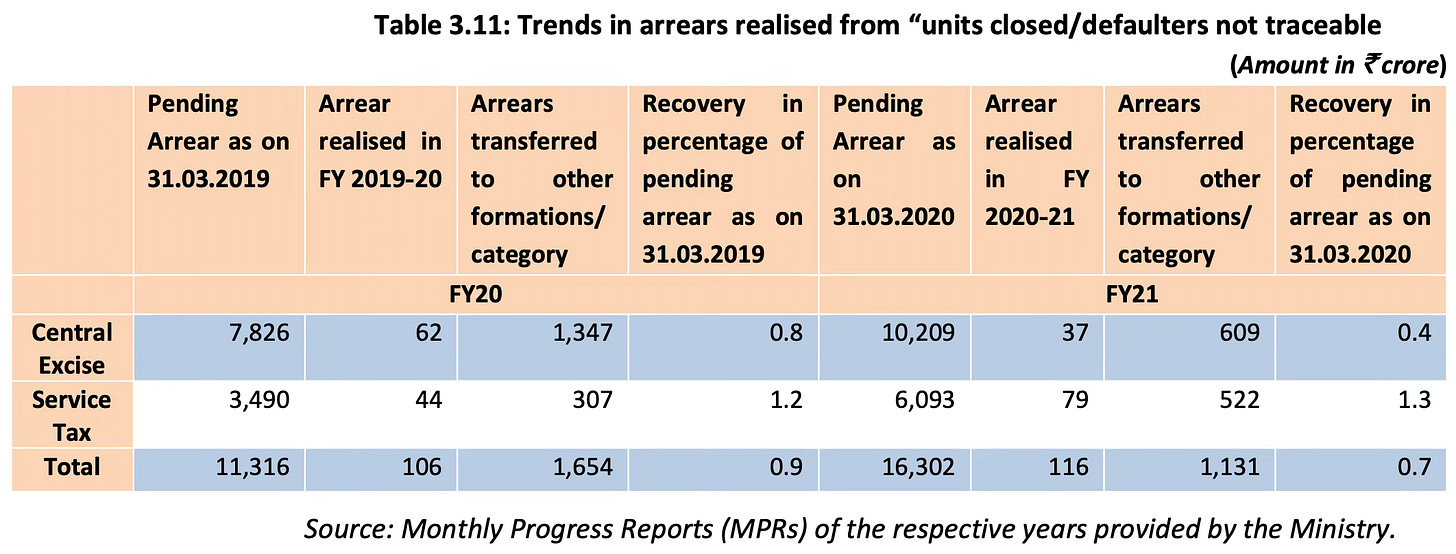

The CAG’s compliance audit report on GST for 2022 reveals some interesting insights on service and excise tax under the Central Excise Act 1944. The Table shows limited progress in recovery of arrears.

Realisation from closed units is negligible.

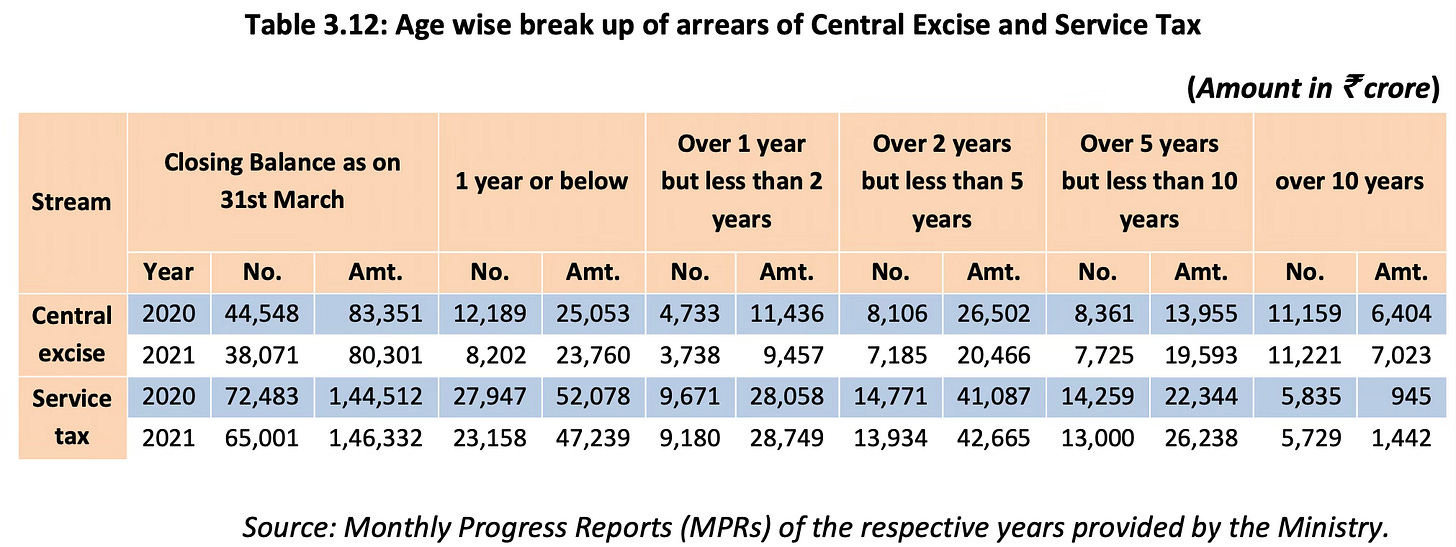

The age-wise break-up of pending arrears is in the table.

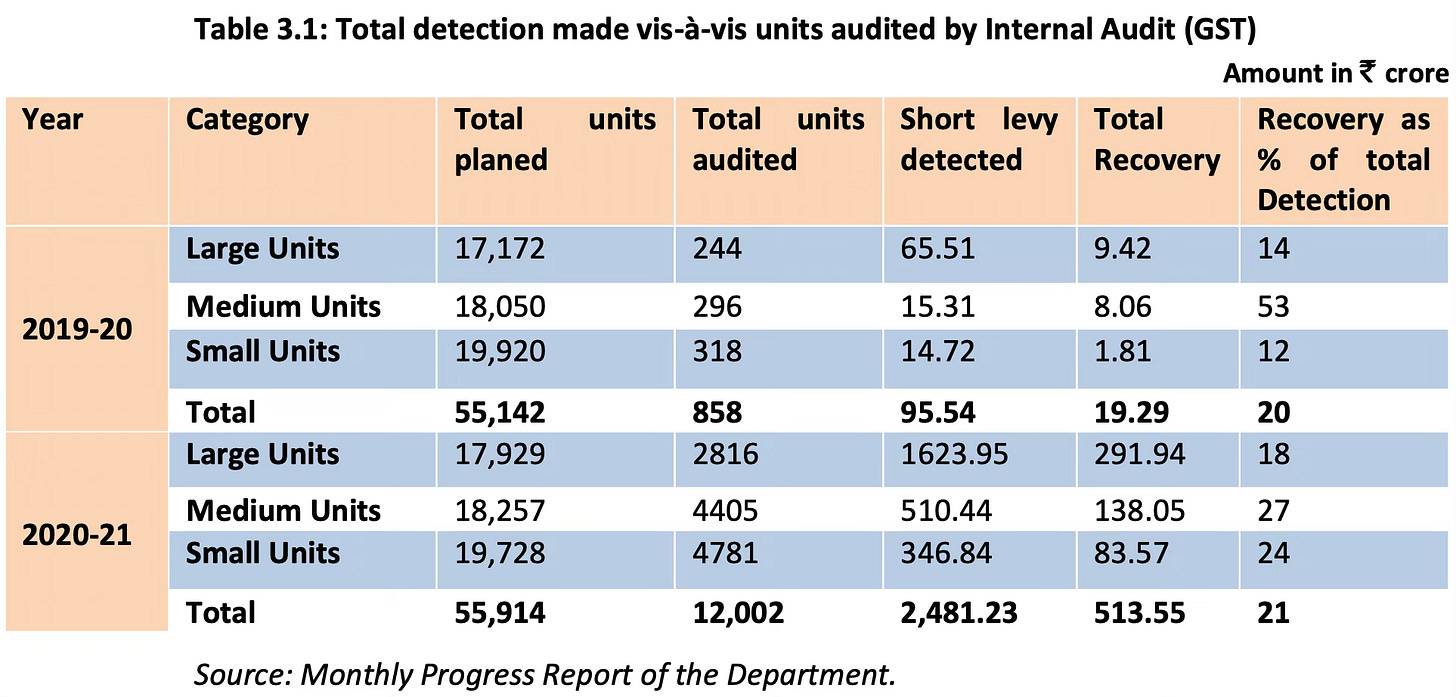

The two graphics below show the percentage of detections and recoveries in GST…

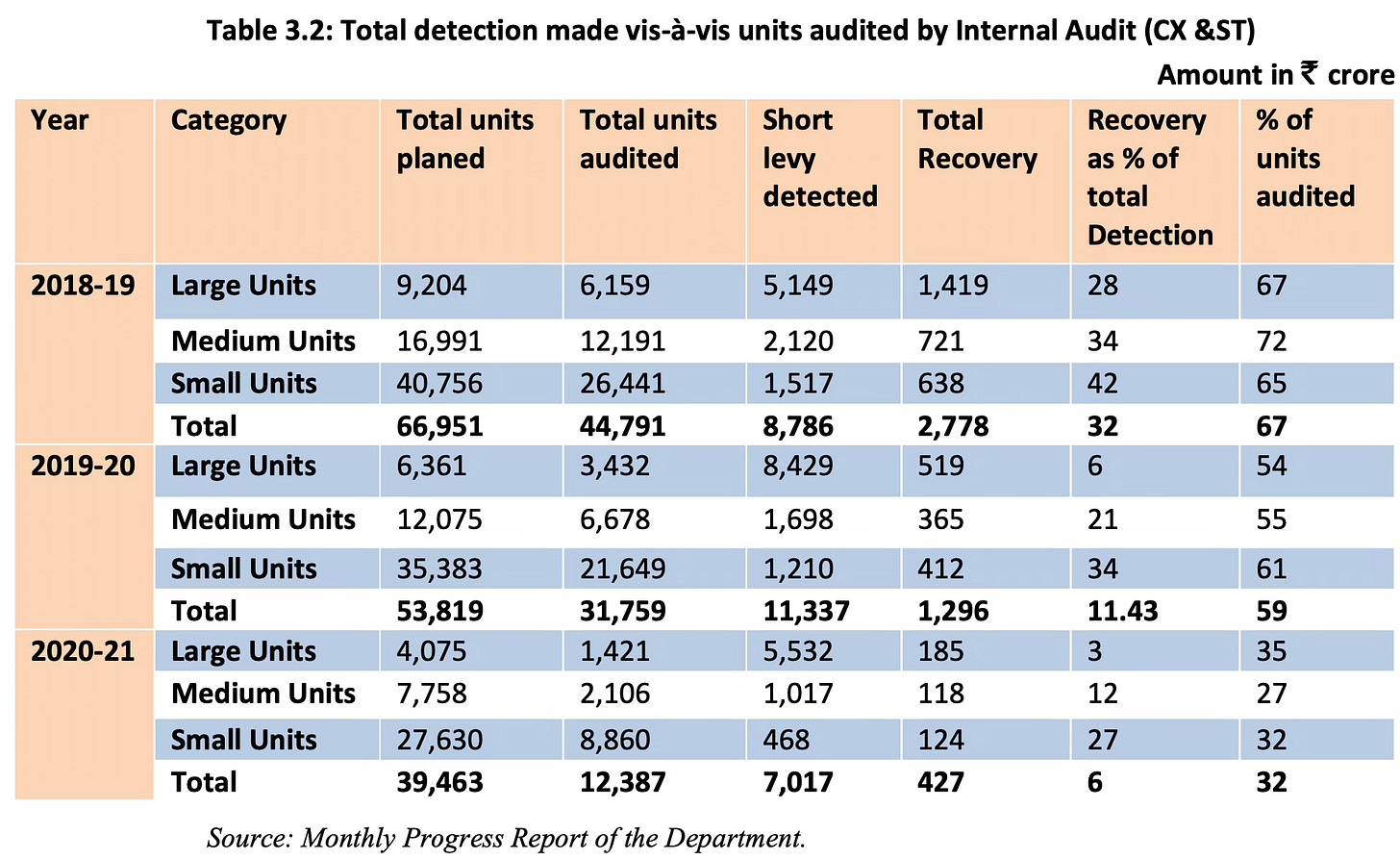

… and Excise and Service Tax.

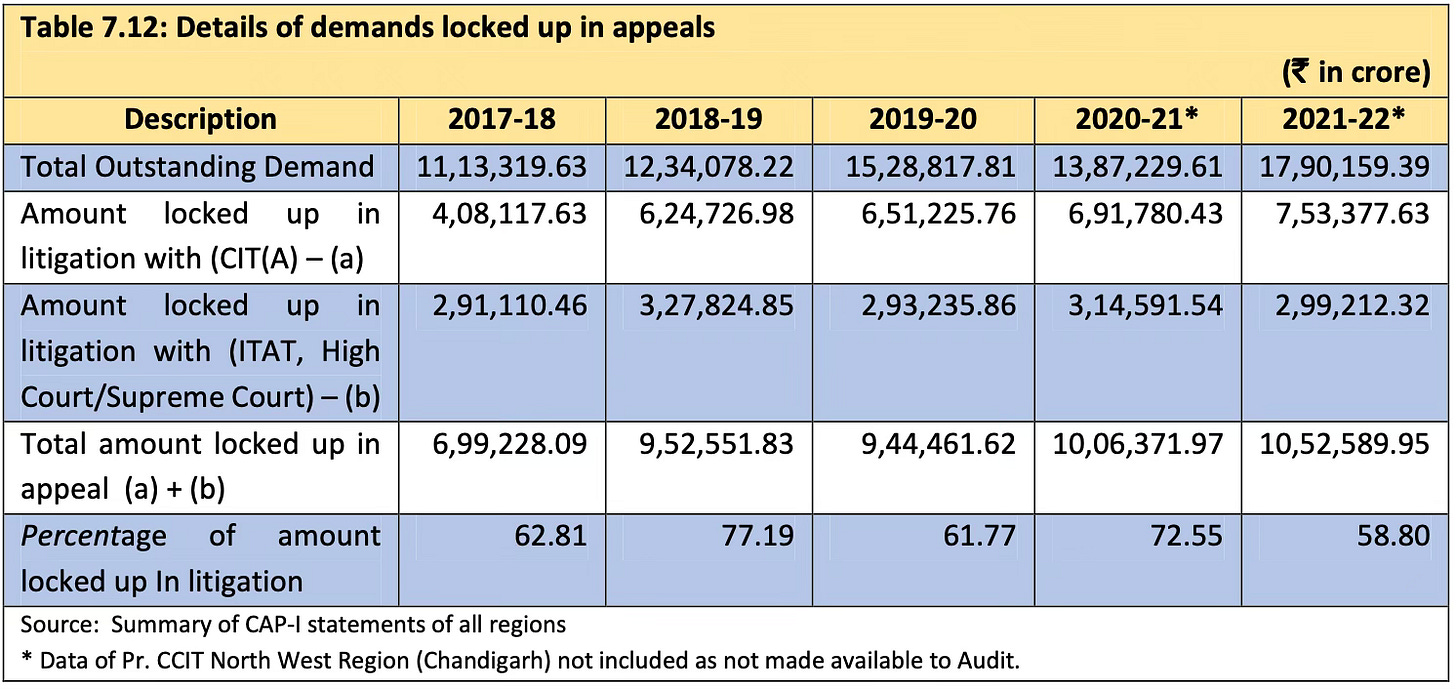

On the direct taxes side, the CAG’s compliance audit on the outstanding demand on income tax assessees for FY22 reveals the following table (HT: The Wire).

An analysis of ‘total outstanding demand’ and demand classified by the ITD as ‘difficult to recover’ vis-à-vis the ‘total direct tax collection’ for the financial years 2016-17, 2017-18, 2018-19 and 2019-20 showed that total outstanding demand had exceeded direct tax collections consistently. The demand classified by the ITD as 'difficult to recover' was more than 97 per cent of the total outstanding demand in all these years.

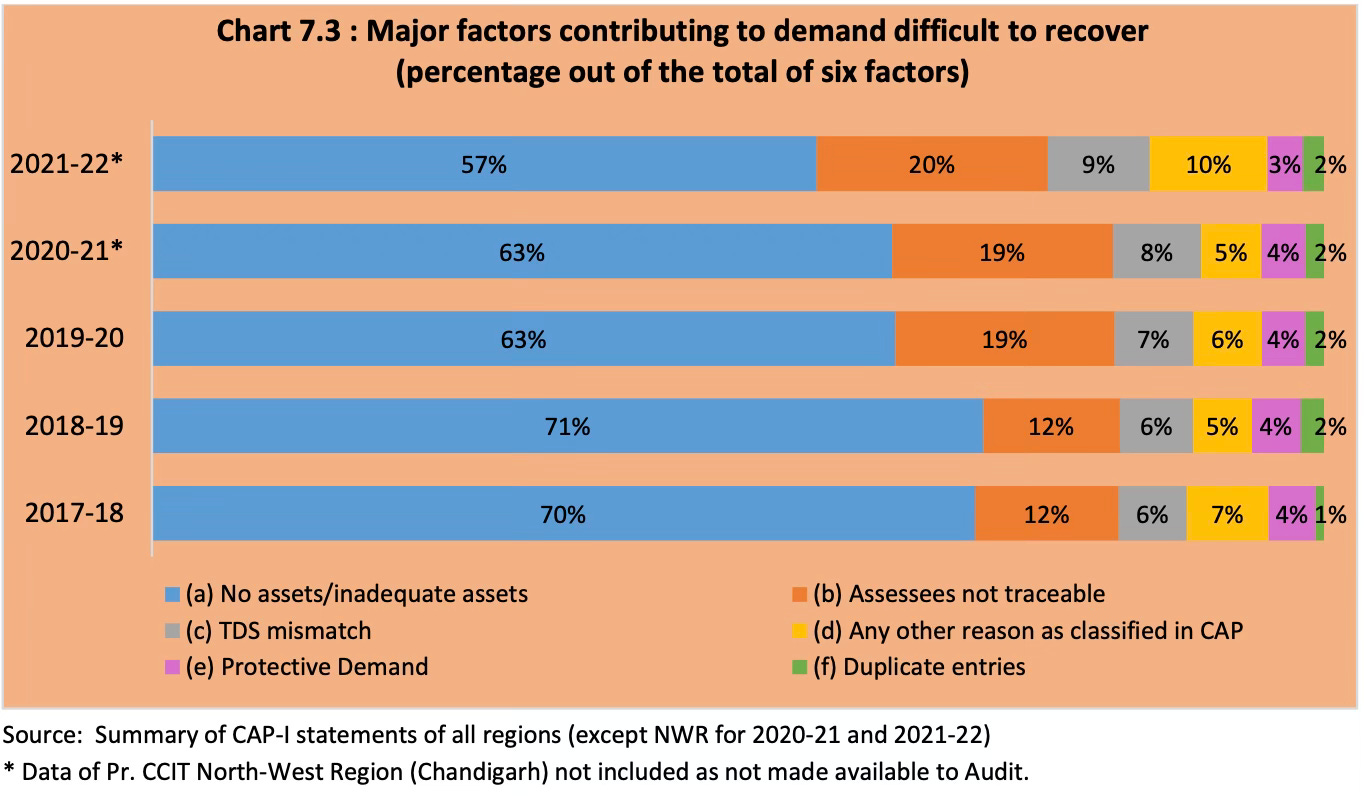

The Table captures the different reasons for the demand difficult to recover.

The amounts locked up in litigation range from 59% to 77%.

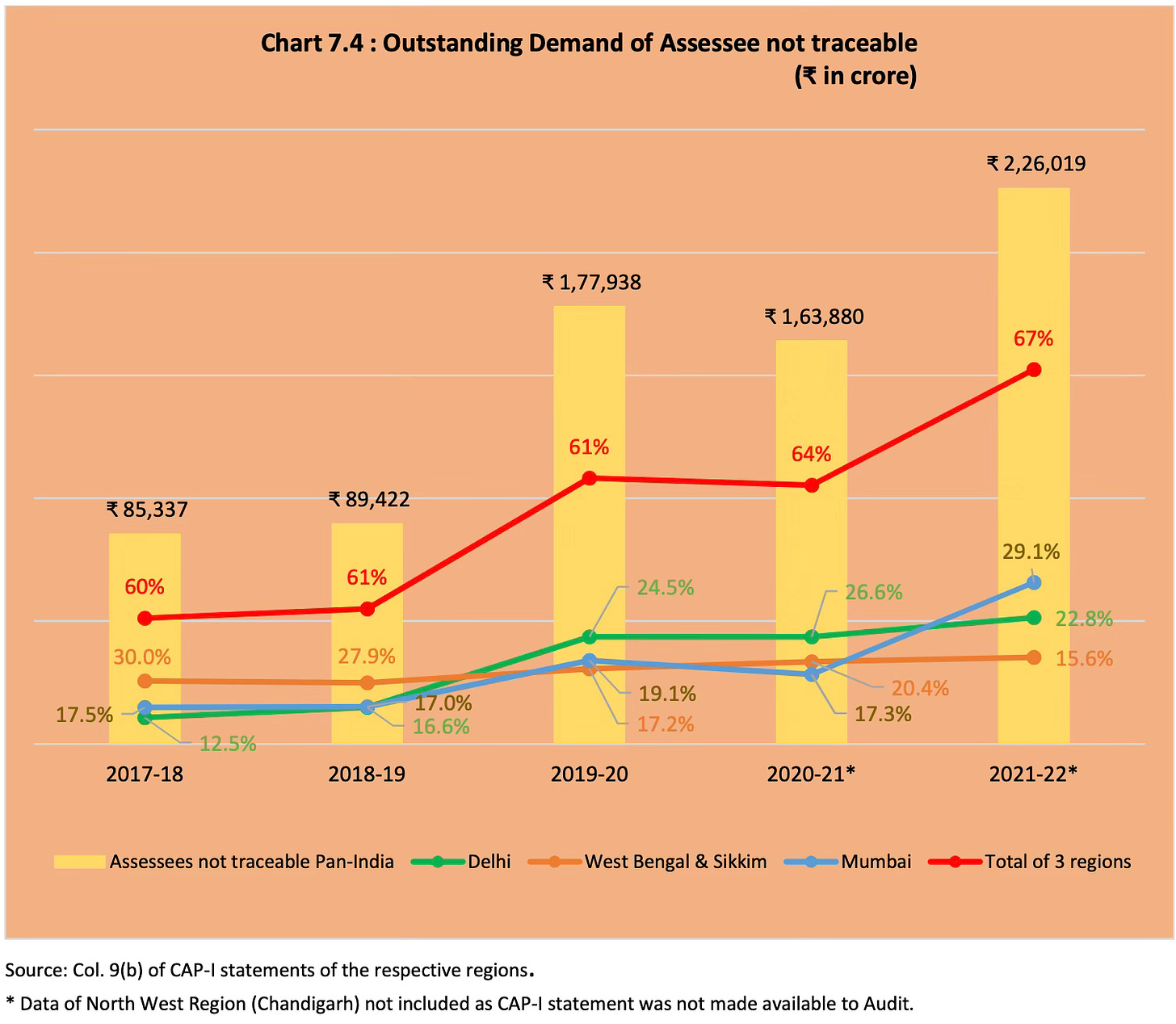

The figure of outstanding demand against the ‘assessees not traceable’ more than doubled in 2019-20 and tripled from 2017-18, despite linking PAN with Aadhaar being mandatory since July 2017.

All compliance audit reports of CAG can be found here.

A few observations.

1. Arrear collections are a dissipative endeavour. For a new officer or government, notwithstanding its persistence over the years, the large arrear pending provides an alluring attraction. A disproportionate amount of effort is expended on arrears with limited results. On a pure cost-benefit analysis, the realisations are often offset by the manpower costs involved, much less the opportunity costs from displaced efforts.

2. There’s an iron law of arrears - the difficulty of collection increases exponentially with its age. The best time to collect an arrear is in the first year. Once it exceeds the first year, it becomes extremely difficult to recover. Tax authorities should, therefore, focus efforts on collecting dues pending for less than a year.

3. Once a case goes into litigation, it’s inevitable that the assessee will litigate till the final court of appeal. This also means several years for which the amounts are locked in litigation. Finally, only a tiny share of those cases result in actual realisations. The amounts realised after the completion of litigation are likely to be rounding errors.

4. It’s not out of place here to say that the courts also play their role in the accumulation of cases in litigation. While inordinate delays are the common culprit, a less-discussed contributor is the propensity in many courts to admit cases at various stages of investigation, adjudication, and appeal. The taxpayers tend to prefer this route since it allows them to pay a small amount and delay the due process before the tax authorities. Collusion among all stakeholders ensures that the case gets delayed interminably.

In this context, I had blogged here with several actionable suggestions to address such excessive demands.

Apart from procedural reforms, there’s also the need for some form of performance management of officers in tax departments. Specifically, there should be a mechanism to rigorously monitor the quality of their assessment and enforcement work.

As a framework, allocation of cases for investigations should be based on signatures of high likelihood of evasion (also ideally high-value evasion for audits and inspections). Investigations should avoid false positives that harass innocent taxpayers with notices and procedural pain. Similarly, the quality of investigation and adjudication should strive to target deviations in the least invasive manner and should result in realisations that are close to the initial demand.

Accordingly, any investigation can be reduced to four stages - assignment of the case and issue of notice, detection of deviation and raising of preliminary demand, adjudication and issue of final demand, and collection. The detection rate (detected cases/total cases identified for issue of notice) is a measure of the quality of assignment or allocation. The ratio of final demand to initial demand is a measure of the quality of the investigation. The ratio of collection to the final demand raised is a measure of the quality of adjudication (and collection). Finally, there’s the average realisation per case, which is a measure of the combined quality of the tax enforcement work (this last metric will also ensure that officials don’t game the system by raising several small tax demands).

These metrics can be customised based on the specific sequence of processes associated with each tax agency.

Taken together, at a steady state and over the tenure of an officer, these four ratios should give a reliable assessment of the quality of the assignment, investigation, adjudication, and collection. It might, therefore, be useful for the tax authorities to devise benchmarks for each stage and have all tax officials performing these roles assessed for the duration of their tenures on these metrics. These performance metrics should inform the postings of officers and the assignment of cases.

In fact, if historical data on these metrics can be assessed for each senior officer (along the lines discussed here), then it might be a good basis for identifying officers who have the propensity for aggressive demand-raising. The CBDT and CBIC could invite academic researchers and offer them access to their databases and have them analyse and generate the reports as required (while also allowing them to publish on the headline findings).

No comments:

Post a Comment