The RBI has just published a report on municipal government finances. It lays bare one of the biggest concerns in India’s urban development agenda, one that I feel does not get its due attention.

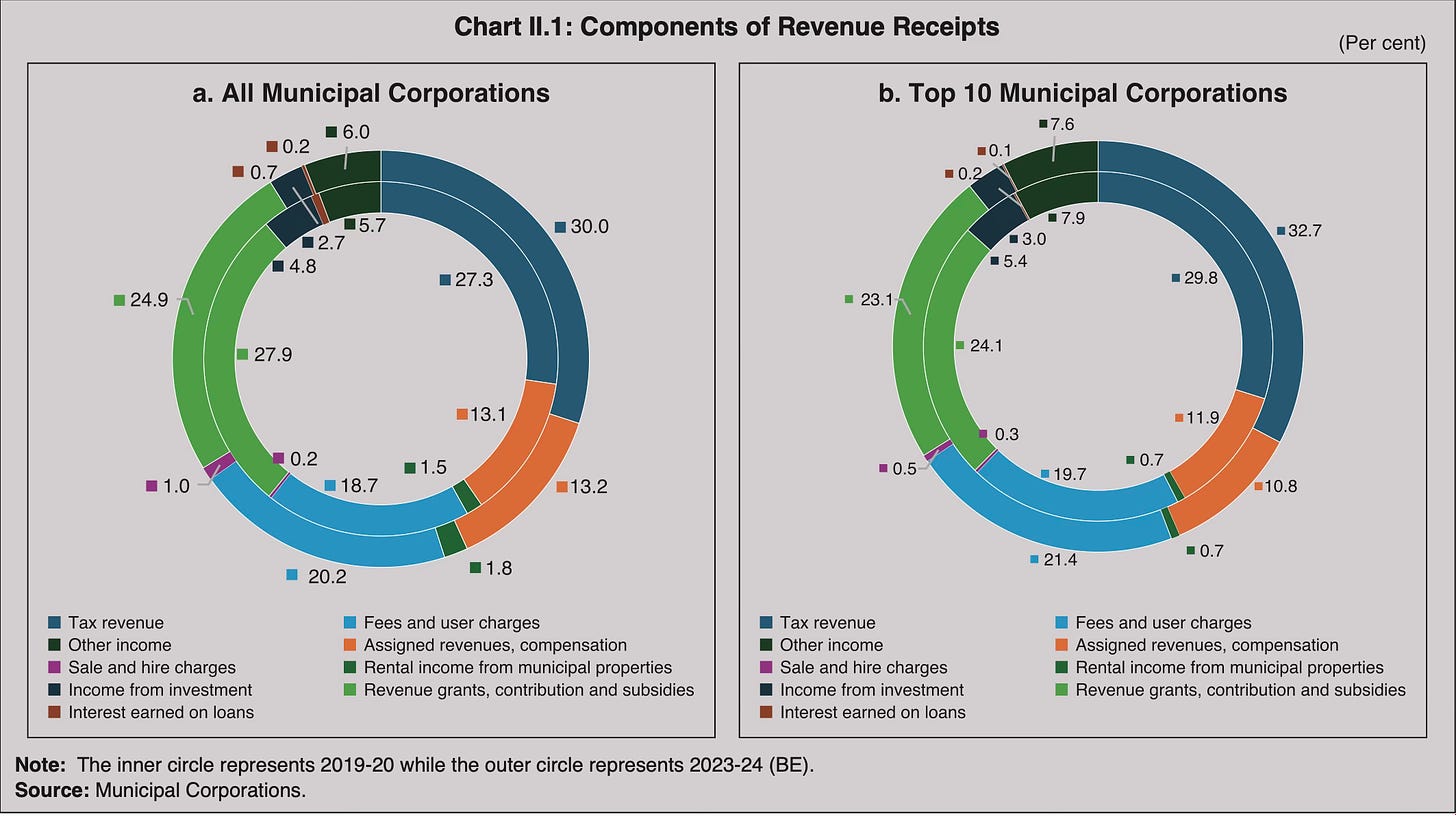

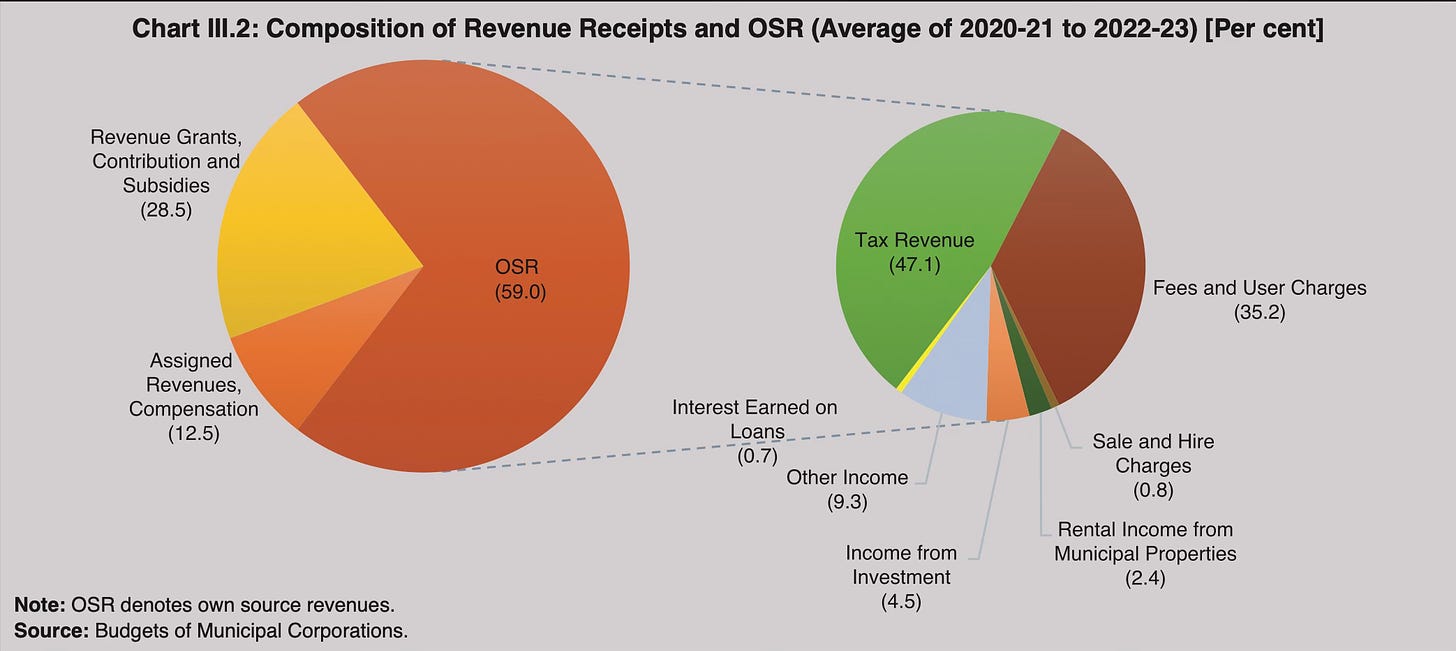

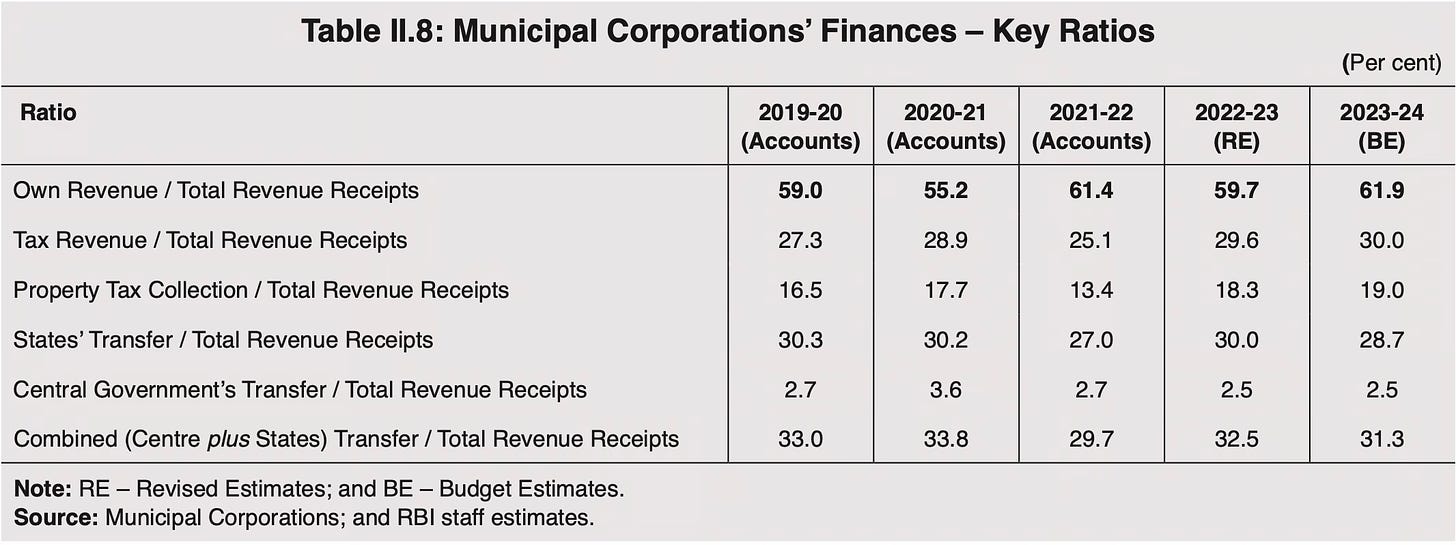

The total revenue receipts (RRs) of 232 municipal corporations studied was Rs 1.7 trillion (~$20 billion) in 2023-24 BE (compared to Rs 1.42 trillion in 2022-23). This amounts to 0.6% of GDP, the same as in 2019-20 and consistently the same throughout the period. Property tax revenues of these corporations was just Rs 32,450 Cr (~$3.9 billion)! In other words, property tax revenues formed just 0.12% of GDP (add the remaining municipalities, and it’ll come to no more than 0.15%)! Tax revenues made up 30% of total RRs, followed by revenue grants and transfers at 24.9%, and fees and user charges at 20.2%.

The top 10 municipal corporations account for 58% of all RRs at Rs 98,508 Cr (less than $12 billion). Their property tax revenues were just Rs 20,595 Cr (~$2.5 bn). In other words, the 222 other corporations are estimated to raise just $1.4 billion as property tax in 2023-24.

The RRs of MCs look really miniscule when compared to their state government RRs. It’s estimated to be 4% in 2023-24, up from 3.6% in 2022-23 but down from 4.2% in 2019-20. This conceals a wide variation, from the 30-35% range of Delhi to 14-16% range of Maharashtra to 6-8% range of Gujarat to the 1-3% range for most other states. While own tax revenues (OTR) made up 30% of total RRs, property taxes are the major source of OTR of the MCs, making more than 16% of revenue receipts and more than 60% of their OTR. It’s disturbing that these ratios have hardly changed over the years.

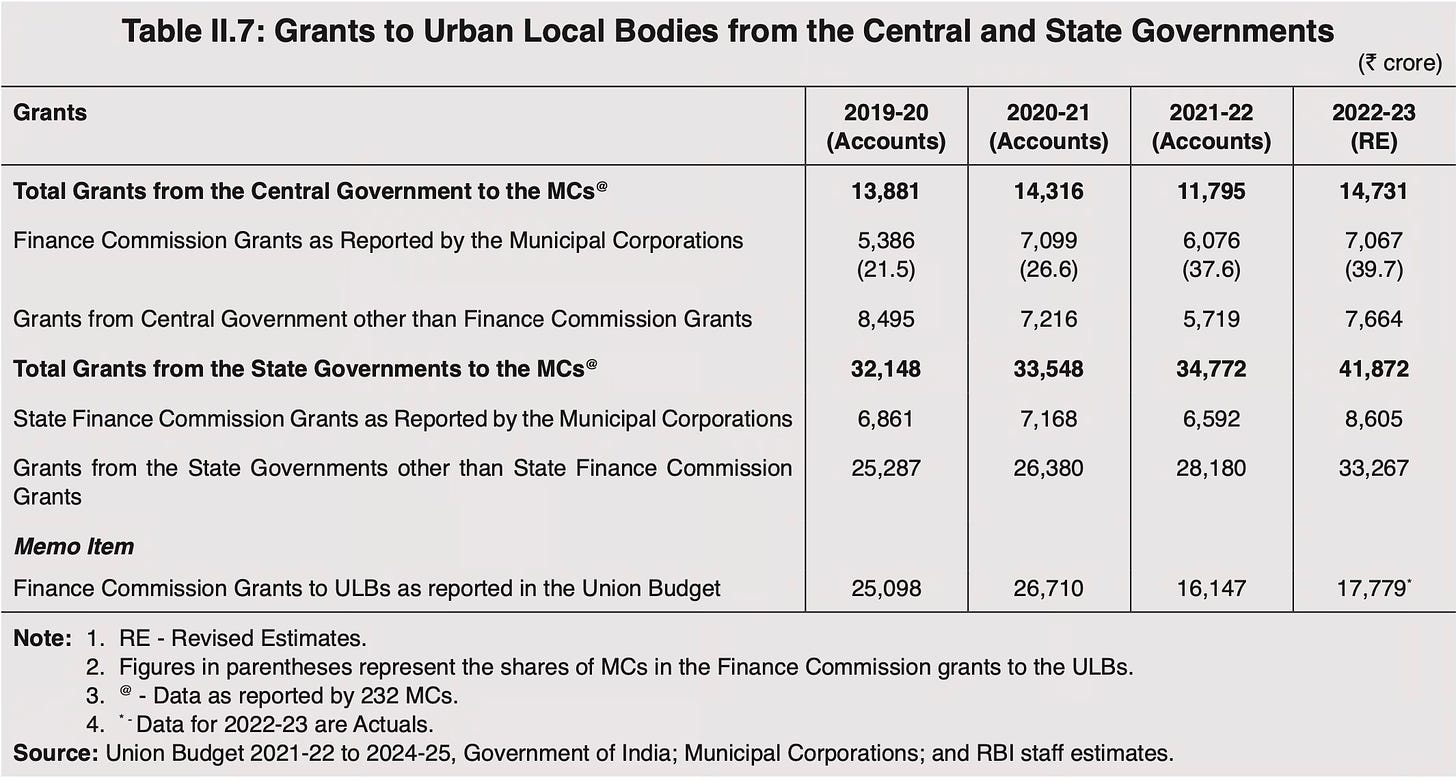

The grants from state and central governments amounted to just Rs 41,872 Cr (~$ 5 bn) and Rs 14,731 Cr (~$ 1.8 bn) respectively in 2022-23.

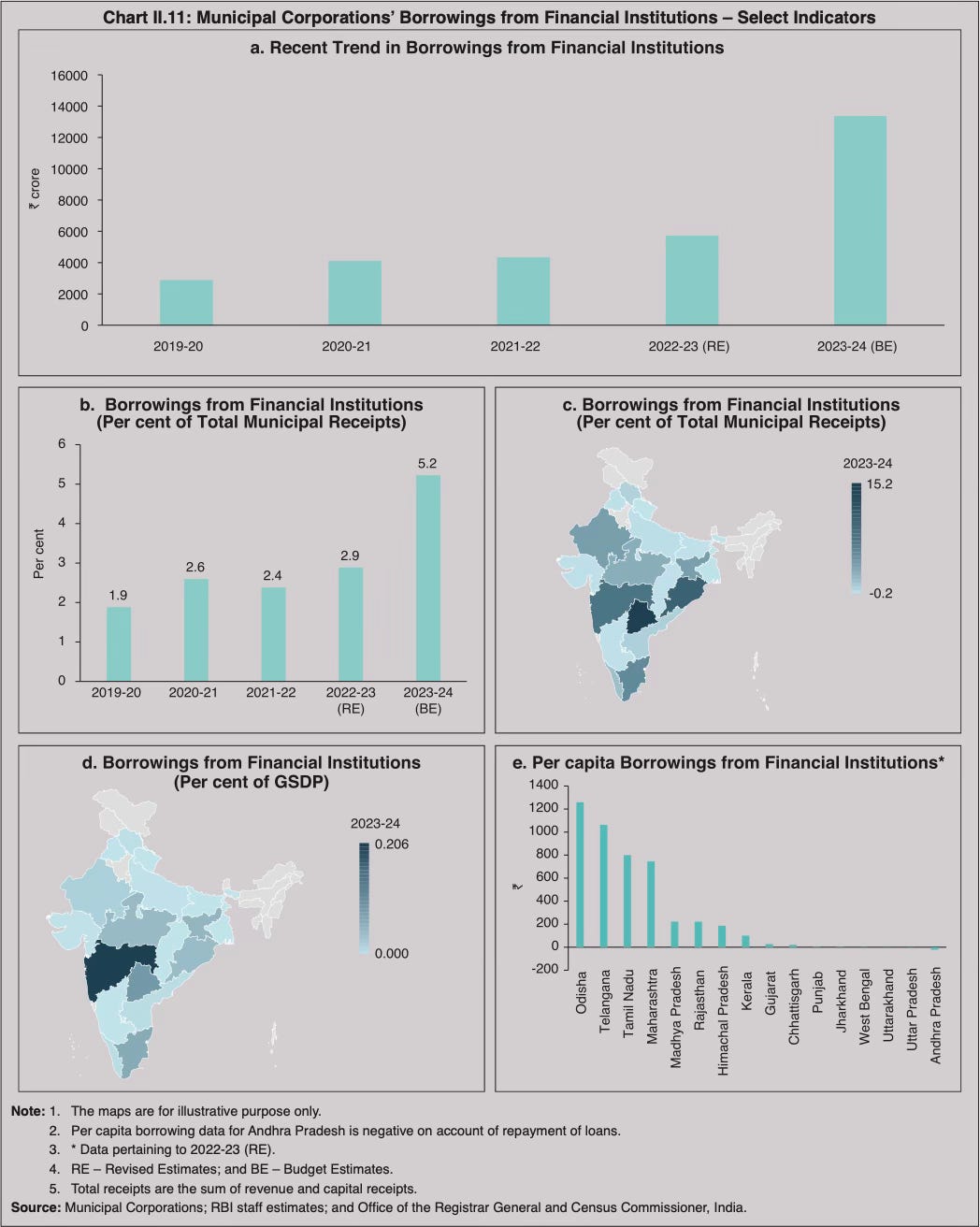

MCs in India have generally had low borrowings, rising from just Rs 2886 Cr in 2019-20 to an estimated Rs 13,364 Cr in 2023-24 BE, accounting for just 5.2% of total RRs. Municipal borrowings formed a negligible 0.05% of GDP for all MCs. Interest payments made up just Rs 5675 Cr in 2023-24BE. Municipal bonds have not taken off, with a few hundred crores issued each year and just Rs 4204 Cr outstanding on 31.03.2024.

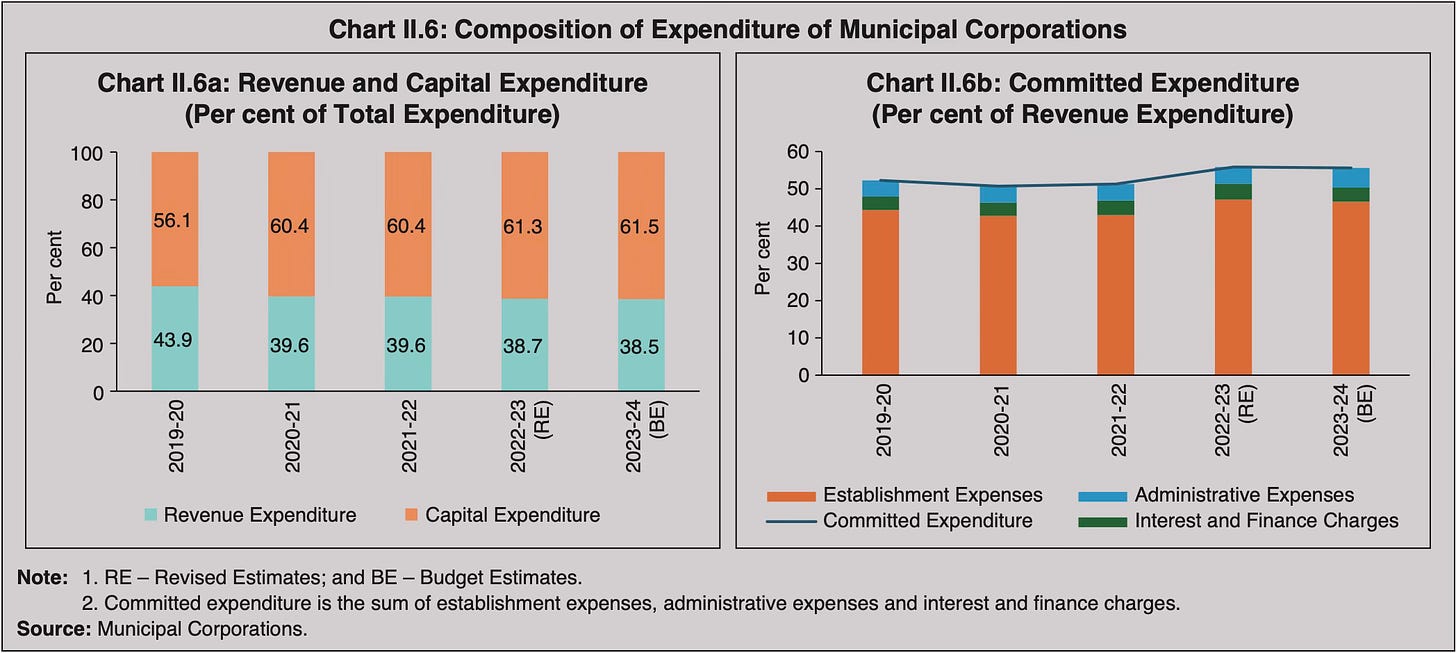

On the expenditure side, the revenue and capital spending combined of MCs rose from 1.2% of GDP in 2019-20 to 1.3% in 2023-24BE. The revenue expenditure as a share of GDP has hovered around 0.5% and that of capital expenditure has been 0.7-0.8%.

In absolute terms, the total expenditure estimates of the 232 MCs for 2023-24BE is Rs 3.9 trillion (~$47 bn), of which revenue expenditure if Rs 1.5 trillion and capital is Rs 2.4 trillion (~$29 bn). The same figures for the top 10 MCs being Rs 1.9, Rs 0.8 and Rs 1.1 trillion respectively. The ratios have remained stable in recent years.

In fact, the total fixed assets created and under creation during the year 2022-23 RE was just Rs 1.8 trillion (~$21.7 bn).

One positive feature is that the ratio of revenue to capital expenditures was 0.63 for the MCs in 2023-24 (BE) as against 3.7 for the Centre and 3.0 for the States, reflecting better quality of expenditures. However, it must be noted that these expenditure data must account for the salaries of municipal employees which in atleast some states is borned by the state governments.

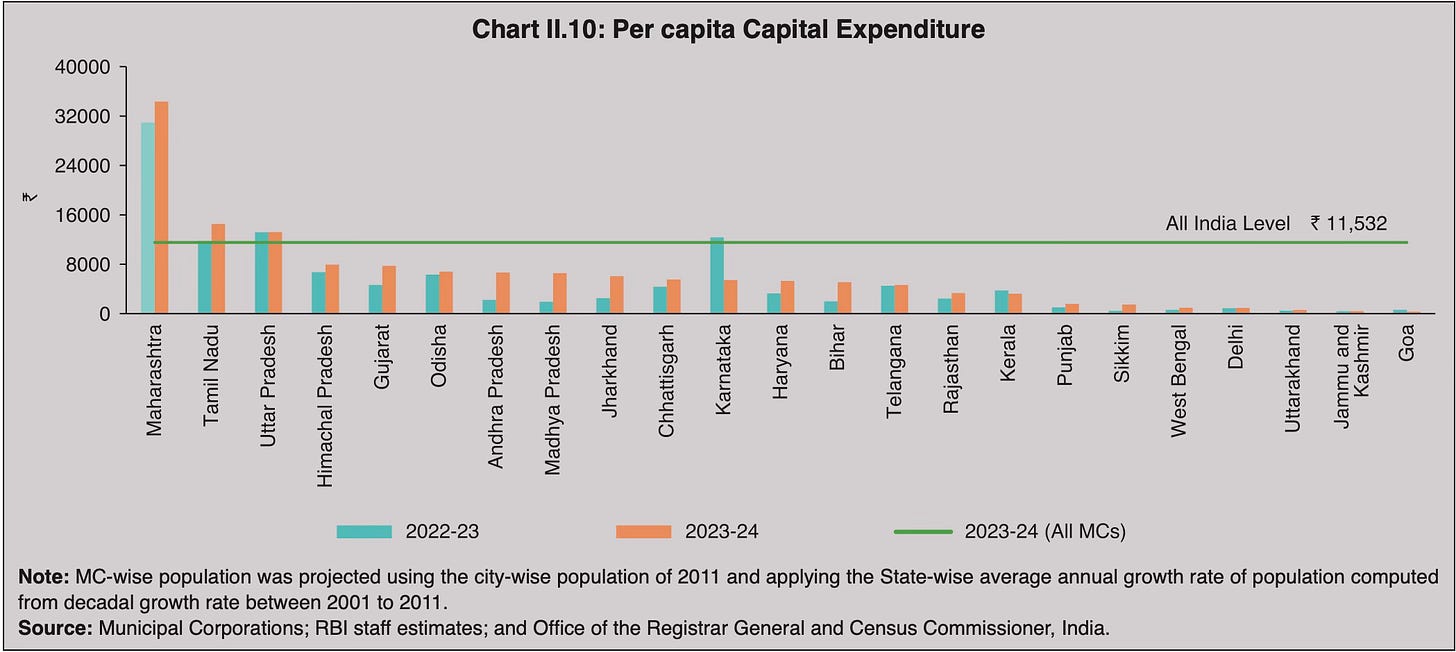

Underlining the low level of expenditures, the per capita capital expenditure across states is very low.

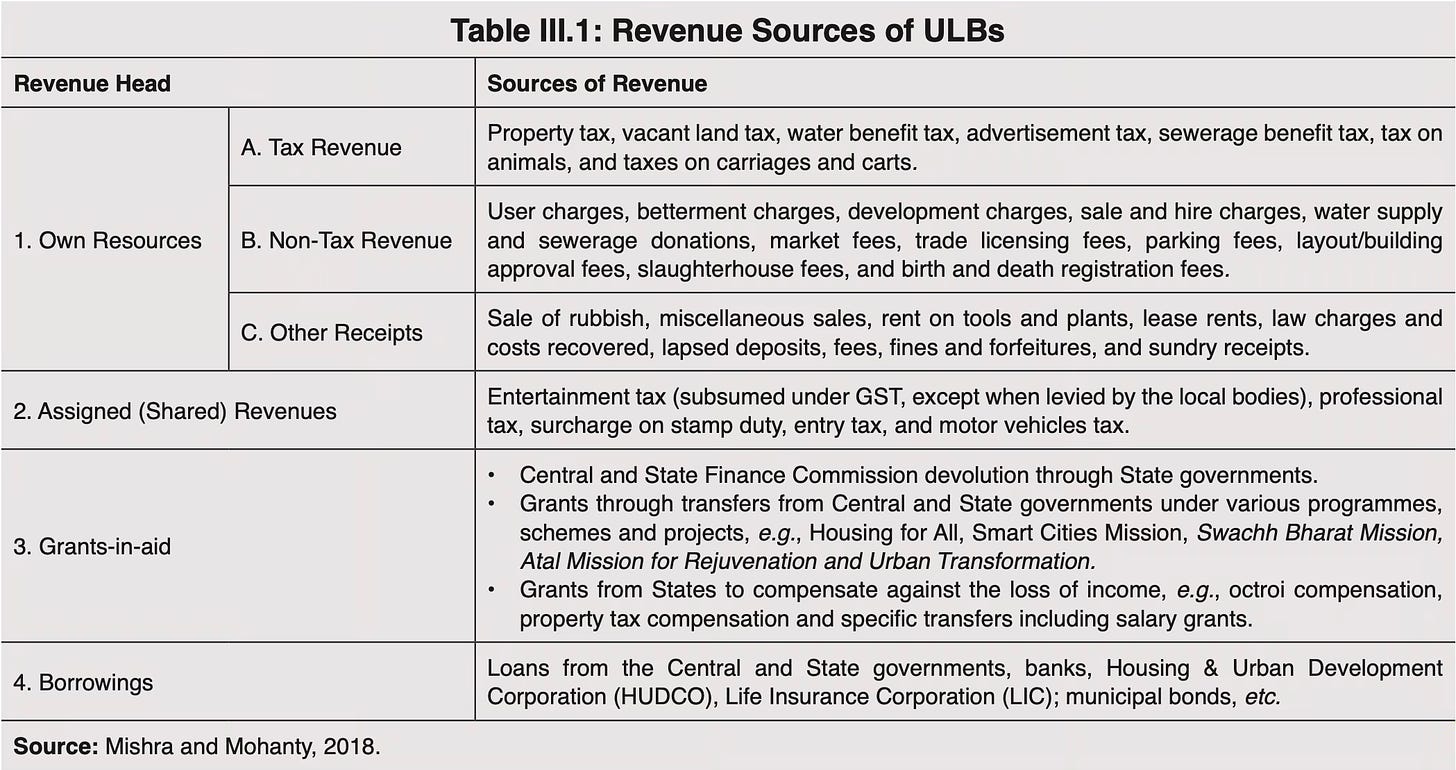

The report has a good summary of all the revenue sources of municipalities.

A few observations based on these findings.

1. India’s property tax revenues are shockingly low at a mere 0.12% of GDP. Increasing it significantly should become the biggest priority for urban local governments and for central and state governments in their urban agenda. There should be a policy focus to increase it from its current low baseline to about 1% of GDP over the next five years and 1.5% over the next ten years. Some times such targets can be useful.

Stuck at such low levels, and being just 1-2% of the state government revenue receipts, municipal revenues have become a rounding error. The vast majority of municipalities have become extended parts of the state government. Therefore, apart from the big cities, there’s no system-wide incentive to focus on expansion of the tax base and collection.

The 16th Finance Commission should consider devoting significant space in its recommendations on the issue of property tax and other own source revenues of municipalities and propose measures to expand their base.

Increasing property tax revenues should become as much a priority as increasing tax to GDP revenues of the central government.

2. In the pursuit to raise property tax revenues from its current abysmal baseline, the following could be done by governments at all three levels.

(a) Given the low baseline, urban local governments should prioritise basic good governance in their tax administration over applications of innovations and technologies. The administrative bandwidth of the MCs should be focused on the plumbing issues of constant updation of their assessment value registers, detection of un-assessed and more importantly under-assessed properties, and expansion of the base of vacant land tax, apart from improvements to collection efficiencies.

In general, Municipal Commissioners should single-mindedly focus on expanding the tax base and ensuring collections. This should become the predominant review parameter of Commissioners by the state government Municipal Administration Departments.

(b) State governments should focus on shifting towards capital value method of property tax assessments, removing exemptions given to various categories of properties, and significantly raising the property tax rates for the higher slabs. There should be clear 5-year glide paths for these revisions to achieve some benchmark tax revenue targets.

(c) A major source of revenue loss and exemption for local governments arises from the state and central government properties. State government properties routinely default and state government provides exemptions to educational institutions, industries etc. The 16th Finance Commission could consider advising that all exemptions on property taxes given by state governments should be compensated from the Budget and all property tax dues on state government properties should be reimbursed promptly to local governments.

In fact, central government could consider emulating the power sector where all central government support to state’s power utilities have been made contingent on prompt releases of subsidy and current charge dues of public facilities by state governments. Similarly, all central government scheme releases should be made contingent on reimbursement of all property tax dues to the local bodies.

(d) While there are no reliable assessments on the property tax foregone by municipalities across the country on defence, railways, central government offices, and central Public Sector Units (PSUs), it’s certain to be a very large amount. Central government properties claim exemption under Article 285(1) which prohibits all taxation on them. However, as laid down by the Supreme Court (and acknowledged by central government here), this exemption does not cover fees or service charges or other charges levied by local governments. This provides a window to address the festering problem.

In any case, the provision of Article 285(1) is an anachronism and should be revisited by the central government. This is especially important since the local government bears considerable actual costs in providing connectivity and trunk utility access to these central government properties, besides the costs of the externalities arising from their presence. These costs are currently a subsidy from the local government to the central government. It’s therefore only appropriate that the central government either consider amending Article 285(1) or allow local governments to monetise and collect the costs incurred by them in some uniform manner as service charge, and provide for these amounts in the budget allocations of the respective central government departments.

The 16th Finance Commission too should consider advising the central government in this regard in its recommendations. For a start, it could do great by just documenting and monetising the property tax revenues foregone by local governments due to the exemptions granted to central government entities. But a strong recommendation to consider an amendment to Article 285(1) might just be the impetus needed to stir up a vigorous and honest debate on this issue.

3. The focus on property tax revenues should be complemented with augmenting non-tax revenues. Instead of fixed rates, building permissions and other layout development and construction fees should be indexed to capital value, at least for buildings and properties beyond a certain value.

In this regard, as I blogged here municipalities should consider the extensive use of land value capture to finance large investments. They should also consider amending the building regulations and manadating purchase of building rights as discussed here and here.

Municipal revenue augmentation should focus on lower-hanging plumbing issues instead of being stuck on fancy ideas like municipal bonds.

4. On the debt side, the low level of leverage of municipalities offers a great opportunity to raise revenues to supplement the limited own revenues. But in the prevailing conditions of poor municipal finance accounting and governance, such debt mobilisation should be done very carefully and under very tight end-use monitoring and utilisation by the state and central governments and banking regulator.

Instead of focussing all efforts on fancy ideas like Municipal Bonds (and municipal bonds are indeed fancy for all but a tiny few Corporations), central and state governments should instead prioritise greater access for municipal governments to bank loans. Like with infrastructure sector generally, contrary to the opinion makers fetish with capital mobilisation through the bond market, bank loans will remain the major source debt finance to cities for the foreseeable future.

Accordingly, the policy focus should be on bank financing structures like project loans without recourse to municipal general funds, credit guarantees, loan syndication, pooled financing etc. The infrastructure DFIs like NIIF, IIFCL, and NaBFID have important roles to play in the promotion of bank financing through these channels. I have blogged multiple times on bank financing of infrastructure, see for instance this, this and this.

Finally, I want to point to a few major methodological flaws with the report. For a report published by an institution like the RBI, its accounting of revenue and capital receipts is riddled with inaccuracies and inconsistencies. All transfers from state and central governments as grants are part of revenue receipts. This would include statutory transfers (Finance Commission and state government transfers), central government schemes, and all other grants. The RRs are different places in the report are inconsistent. It also does not contain information on the capital receipts of MCs. As a result, there’s the accounting gap between, for example, the total RR of Rs 1.7 trillion and total expenditure of Rs 3.9 trillion for 2023-24BE. This accounting gap would consist of loans and proceeds from sales of assets. The report does not explain this large gap.

No comments:

Post a Comment