1. The Economist on whether India can outcompete Bangladesh in textile exports

Since building its first export-orientated apparel factory in 1978, a joint venture with a South Korean firm, Bangladesh has turned its economy into a clothes-exporting powerhouse. The sector employs some 4m people, mostly women, and contributes 10% of the country’s GDP. Last year Bangladesh shipped $54bn-worth of garments, second only to China... India does not have the capacity to compete with Bangladesh at this stage, according to one industry insider. Too much policy attention is directed towards boosting capital-intensive sectors, such as electronics, instead of labour-intensive textiles, he says. Between 2016 and 2023 the value of Indian apparel exports fell by 15%, whereas Bangladesh’s increased by 63%. A recent World Bank report points to India’s protectionist policies as the culprit. Average import tariffs on textiles and apparel, including on intermediate inputs used by local manufacturers, have increased by 13 percentage points since 2017, raising prices for producers.

2. Some data on India's services-led growth

Over the last decade, India has added close to $1.7 trillion to its nominal GDP, 52% of which came from the services sector, compared to 11% from manufacturing. Services are far less capital intensive, as they do not require heavy machinery and large factories . Thus, the capital intensity of Indian growth has fallen in tandem... A booming services sector also leads to a concentration of the economic surplus. The backward linkages of this sector happen to be relatively weak. For each additional dollar worth of output by it, only 30 cents reflects the inputs it absorbs from other sectors in the economy. For the manufacturing sector, in contrast, this proportion is much higher at 73 cents... Industrial production data shows sectors (mostly low-tech) that account for 15% of manufacturing output have still not reclaimed their pre-pandemic output. In some of these, such as leather and apparel, production is still down by more a fifth from their pre-pandemic levels.

3. Some important findings from the Annual Survey of Unincorporated Sector Enterprises (ASUSE) of 2021-22 and 2022-23.

Presently, there are 14.6 million active taxpayers, of which nearly 10.4 million have come in the post-GST regime and are therefore new registrations. They represent a formalization of the economy... Over the two surveys, from 2021 till 2023, the number of enterprises rose from 59.7 to 65.4 million, and the corresponding employment from 97.9 million to 109.6 million. The employment numbers include single person-owned enterprises and are lower than in the 2016 survey... Of the 65.4 million enterprises, 82.6% have an annual turnover of less than ₹5 lakh. Almost 99% of the unincorporated enterprises have turnover of less than ₹50 lakhs, and merely 0.3% have more than ₹1 crore. More tellingly, only 2% are registered for GST. Two-thirds of all unincorporated enterprises are not registered under any act or authority. Note, a lot of the benefits to small businesses are linked to their registration on UDYAM. These include collateral free loans under schemes like the Credit Guarantee Fund Trust for Micro and Small Enterprises... A large section of informal small businesses involves sales of products and services directly to the end customer at wafer thin margins. These could be, for instance, selling vegetables or carrying out shoe repair, and often are single-person enterprises. For them, entering the GST net has a disincentive, even if they grow above the exemption threshold, since they do not derive any input tax credit, nor can they pass on the burden to their customer due to a competitive market.

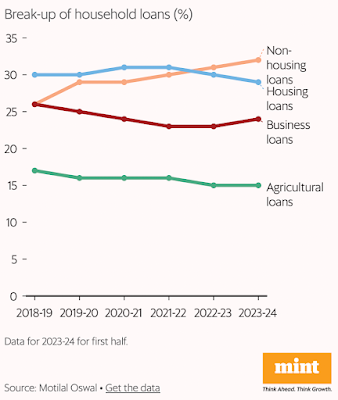

4. Official data has shown that the net financial assets of Indian households declined precipitously from 11.5% of GDP in 2020-21 to 5.1% of GDP in 2022-23, a five-decade low and a fall of over Rs 9 trillion.

The article says that the decline cannot be explained by the rise in physical assets.As part of the bailout, Beijing would authorise local governments to issue bonds over three to five years to restructure most of an estimated Rmb14tn in “hidden” or “implicit” debts, finance minister Lan Fo’an said in a rare press briefing at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing. These debts are mostly held by thousands of off-balance sheet finance vehicles that local governments used to invest in infrastructure and property-related sectors. Many of these bets went sour when China’s real estate market entered a deep slowdown three years ago, sinking local government finances and undermining the broader economy... Lan said Beijing would authorise local governments to issue Rmb6tn in new bonds over three years for the debt restructuring and would reallocate a further Rmb4tn in previously planned bonds over five years for the same purpose... Local governments would be able to swap these bonds for those of their finance vehicles, bringing the debts on to their own balance sheets. This would lead to lower financing costs, saving Rmb600bn in total, Lan said. Lan estimated that “hidden debts” would be reduced to Rmb2.3tn once the swaps and another debt programme related to slum redevelopment were in place. This would free up resources previously “constrained” by the debt problems and allow local governments to refocus spending on “development and public welfare improvement”, he said. On additional stimulus measures, Lan said officials were “studying” extra steps to recapitalise big banks, buy unfinished properties and strengthen consumption.

This massive fiscal stimulus essentially allows local governments to issue bonds to take on their balance sheets a large proportion of the off-balance sheet debts. It's hard to say this is fiscal stimulus. It's more like monetary stimulus.

This is a longer article. Fundamentally, the debt restructuring of Rmb 10 trillion will allow local governments to convert off-balance sheet loans of LGFVs to longer-maturity, lower-interest liabilities, thereby saving Rmb 600 bn in interest payments over five years and reduce such debt to about Rmb 2 trillion by 2028. However, independent estimates put the LGFV hidden debt at Rmb 60 trillion and not Rmb 14 trillion as claimed by the government.

7. Veterinary care has become the latest in the sectors dominated by independent businesses to fall to private equity investments.

Private equity groups Silver Lake and Shore Capital Partners have struck a deal to create one of the biggest US veterinary care groups valued at $8.6bn, with ambitions to further consolidate a sector historically dominated by independently-owned businesses, said people briefed on the matter. The merger between Southern Veterinary Partners and Mission Veterinary Partners, both of which were part-owned by Shore, will create a network of vet hospitals and clinics spanning more than 750 locations and generating $580mn in yearly earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation. The veterinary sector is benefiting from a surge in demand as people seek care for their animals following a pandemic boom in ownership... As part of the deal, Silver Lake and Shore Capital will make a $4bn fresh equity investment split evenly between them. The newly combined company has raised roughly $3bn of debt, said people briefed on the matter. Southern and Mission’s founders and employees will have shareholdings worth almost $1.5bn rolled over, and a syndicate of large co-investors will fund a few hundred million dollars of extra equity. The new company will carry less leverage than prior to the recapitalisation... People briefed on it said the combined company is likely to pursue more deals to roll up vet clinics and hospitals, as private equity groups play an increasingly dominant role in consolidation sweeping the petcare industry... Bloomberg previously reported that the two private equity groups were in talks over a deal to combine Southern and Mission. Rival company IVC Evidensia is owned by Sweden-based buyout group EQT, while PetVet is owned by KKR. Among the other biggest petcare clinic networks are AEA-backed AmeriVet Veterinary Partners and the veterinary health division of family-owned consumer group Mars, which operates more than 3,000 clinics worldwide. Southern, in which Shore has been an investor since 2014, operates more than 420 locations across the US, while Mission, which Shore helped to found in 2017, operates more than 330 vet hospitals nationwide.

Many private investors have been increasingly showing a preference for single-speciality hospitals, especially since 2022, with deals and fundraising taking place at a brisk pace... This year, in one of the bigger deals so far, Quadria Capital acquired a minority stake in dialysis chain NephroPlus in May for $102 million. In 2022, the healthcare-focused private equity (PE) firm had invested $159 million in eye-care hospital Maxvision... Last year, funding deals worth $5.5 billion were inked by hospitals in India, of which 20% went to single-speciality facilities, according to consulting firm Bain. Among the most prominent deals were Asia Healthcare Holding (AHH)s’ acquisition of Asian Institute of Nephrology and Urology for ₹600 crore ($75 million) and PE firm EQT buying a majority stake in Indira IVF, India’s largest fertility chain, reportedly at a ₹9,000 crore valuation...

Nothing matters more to a PE firm or a similarly aggressive buyer than scaling up a business quickly. Compared to elephantine multispeciality hospitals, single-speciality chains offer a more attractive turnaround time. A multispeciality hospital opening with more than 300 beds in a location can take up to five years to break even... With relatively fewer beds (or none in some cases), these individual hospitals tend to be smaller, making it easier to open many of them in dense urban centres in a short period of time. Smaller spaces also mean a hospital has plenty of existing hospitals and clinics to choose from for a brownfield acquisition... Investors find the single-speciality model attractive because it needs less investment, less space, can be expanded into a chain faster, and tends to have higher prices... That helps the single-speciality-chain model, whose strength is in offering higher-priced, higher-margin procedures at lower fixed costs than those in a multispeciality model... Globally, single speciality hospitals trade at a premium to multispeciality hospitals for several reasons, including higher ROEs... This is because single-speciality chains don’t need to store expensive machinery for multiple diseases, and can use their machinery more than a multispeciality hospital can, leading to a higher asset utilisation and higher margins.

The details of how telecom was liberalised in India are much more complicated, and frankly, some of it has repercussions to this day. In 2001, one of the things that the Indian telecommunication did to ease things was that it allowed players who had a “basic service licence” to offer limited mobility services. I don’t want to get too deep into this, but essentially, this allowed players who offered something called WLL (wireless local loop technology) to expand and offer mobile services to Indians... Existing telecom players complained that this was tantamount to a “backdoor entry”, because it let WLL players become mobile telecom players without having to pay the higher fees that they were paying for spectrum, entry, or revenue share. This made existing Indian telecom companies—Bharti, Hutch, Idea, BPL, and a few others—quite upset... In January, 2001 when the government approved the use of CDMA (Code Division Multiple Access) based Wireless in Local Loop (will) platforms by basic telephony companies to provide ‘limited mobile’ services (within a single Short Distance Charging Area, approximately 250 square km), Reliance made its move. It bid for, and won 17 new licences, to go with the one for Gujarat that it had acquired in 1997...

This specific ruling was the basis on which Reliance stormed into telecom, and changed India forever. Mukesh Ambani, who had just taken over as the head of Reliance Infocomm, countered all claims by saying, “If anyone thinks this is a backdoor entry (into cellular telephony), well, it is a backdoor that was open to all”. In just a couple of years, Reliance launched the now famous ‘Monsoon Hungama’ offer, giving away handsets for free to consumers, offering rock-bottom prices, and driving up adoption of mobile services across the length and breadth of the country. Competitors were forced to respond in kind, and well, the rest is history. And it all began with India’s telecom regulator letting the wireless loop players use their technology to disrupt existing telecom players.

Starlink now threatens to reprise the scenario!

10. On America's envious economy, The Economist writes.

In 1990 America accounted for about two-fifths of the overall gdp of the G7 group of advanced countries; today it is up to about half (see chart). On a per-person basis, American economic output is now about 40% higher than in western Europe and Canada, and 60% higher than in Japan—roughly twice as large as the gaps between them in 1990. Average wages in America’s poorest state, Mississippi, are higher than the averages in Britain, Canada and Germany... Since the start of 2020, just before the covid-19 pandemic, America’s real growth has been 10%, three times the average for the rest of the g7 countries. Among the g20 group, which includes large emerging markets, America is the only one whose output and employment are above pre-pandemic expectations, according to the International Monetary Fund... A decade ago many analysts thought that China would, by now, have overtaken America as the world’s biggest economy at current exchange rates. Instead its gdp has been slipping of late, from about 75% of America’s in 2021 to 65% now.

On productivity

This year the average American worker will generate about $171,000 in economic output, compared with (on purchasing-parity terms) $120,000 in the euro area, $118,000 in Britain and $96,000 in Japan. That represents a 70% increase in labour productivity in America since 1990, well ahead of the increases elsewhere: 29% in Europe, 46% in Britain and 25% in Japan... when assessed on a per-hour basis the gap remains sizeable: 73% productivity growth for American workers since 1990 versus 39% in the euro area, 55% in Britain and 55% in Japan.

Four-fifths of equity futures and options trades in the world now take place in India.

India generates only 3% of the world’s GDP, but has been home to nearly a third of all public listings so far this year, which accounts for a tenth of the capital raised in ipos globally. Unusually among emerging economies, India has successfully translated economic growth into shareholder returns, letting ordinary investors benefit. Stocks there have roared since 2019, even as those in China have fallen by 15%. Analysts at Franklin Templeton, an asset manager, reckon that the correlation between Indian company earnings and gdp growth is closer than in any other emerging market.

The Economist has another article that hails the introduction of the new Rs 250 monthly contribution Mutual Fund.

One in five households today holds shares, up from one in 14 just five years ago. The number is set to rise further... In dollar terms, Indian stocks have risen in price by 80% over the past five years, compared with a 6% rise across emerging markets as a whole... As investment habits have shifted, the share of household assets held in bank deposits has fallen below half...

In August the number of mutual-fund accounts reached 205m, up from 73m in 2021. Most are small: the average holding is under $4,000. The growth is facilitated by a wave of new electronic brokers... Much of the growth has been driven by products available to humbler investors. The number of Systematic Investment Plans (SIPs), a way to invest in mutual funds, has risen from 10m to 99m in the past eight years, with contributions increasing to $24bn in 2023. The funds take monthly instalments from investors. In August they received $2.8bn, continuing a run of record monthly inflows that has, with only rare interruptions, extended back to 2016.

There has also been an explosion in “demat” accounts, short for the dematerialised form in which shares are held. In August their number reached 171m, up by 54% from January last year. But the most extreme aspect of the investment boom is in derivatives trading: India now accounts for 80% of global turnover, and retail investors count for 40% of Indian trading, up from 2% in 2018... In the first three quarters of this year, India’s 258 IPOs accounted for 30% of the global total by number and 12% by the amount of money raised, in an economy that makes up just over 3% of global GDP.

Economists’ free trade prescriptions fail because they do not reflect modern reality... what we have seen in recent decades is countries adopting industrial policies that are designed not to raise their standard of living but to increase exports — in order both to accumulate assets abroad and to establish their advantage in leading edge industries. These are not the market forces of Smith and Ricardo. These are the beggar-thy-neighbour policies that were condemned early in the last century. Countries that run consistently large surpluses are the protectionists in the global economy. Others, like the US, that run perennial huge trade deficits are the victims. They end up trading their assets and the future income from those assets for current consumption. Many economists will say this is all the fault of the victim, and that the US has too low a savings rate. Of course the trade deficit is equal to the difference between a country’s investment and its savings, but the causation runs the other way. Foreign industrial policy creates the deficits and with investment being set by demand for domestic investment, savings must go down. The problem is not the concomitant savings rate. It is the predatory industrial policies.

13. Rana Faroohar writes on the Trump victory

... the market reaction that greeted Trump’s victory, when stocks and risky assets rose while bond prices fell. This is a man who has promised across-the-board import tariffs and support for the US manufacturing sector. That would argue for lower US share prices and a weaker dollar, to make exports more competitive; investors are betting on just the opposite... America Inc under our brand new CEO Trump feels less like a blue-chip and more like a private equity firm: it’s a highly leveraged, short-term play with an average hold time of around four years. Like Trump, private equity is able to strip assets for immediate profit — no matter how important... If Trump is our CEO, is America now a distressed asset? One has to wonder.

14. Is Mumbai's economic growth choking?

Despite being the country’s financial and entertainment hub, Mumbai, accounting for about 20 per cent of the state’s economy, failed to lead the growth charge. Maximum City real GDP grew at 5.9 per cent between 1994 and 2020, significantly slower than the state, with financial services growing at a paltry 3.6 per cent (2005-20). Mumbai suffers mainly from two main challenges — expensive housing and weak transport. The price-to-income ratio (the median price of a 90 square metre apartment relative to median familial disposable income) in Mumbai is around 40, making it one of the most expensive real estate centres in the world. Likewise, road density in the poshest part of Mumbai, the Island City, is around 7 km per square km as against 10 km for Delhi. Furthermore, Mumbai started developing its metro network relatively late. While Delhi has around 400 km of metro network operational, it is close to 50 km in Mumbai, with about 150 km under construction.

15. In one stroke President elect Trump may have neturalised Elon Musk and Vivek Ramaswamy! Both have been tied-up together (it's very unlikely that they will be able to work together and come up with something coherent). It'll "provide advice and guidance from outside the government", thereby ensuring that its role will be purely advisory with little or no teeth in actual implementation. Finally, by giving it time only till July 4, 2026, there's a sunset for this experiment.

16. KP Krishnan has a very good oped on how the structure of Statutory Regulatory Authorities in India, with their delegated power to make and amend laws, detract from federalism.

Urban local bodies (ULBs) require the approval of their respective state governments for borrowing money. With the growth of bond markets, increasingly municipal bonds are replacing institutional borrowings as the mechanism for providing debt to ULBs. Sebi’s regulation of municipal bonds implies that the regulatory arm of the Union Ministry of Finance is exercising control over a subject in the state list. So, the deficit is also material in its impact.

No comments:

Post a Comment