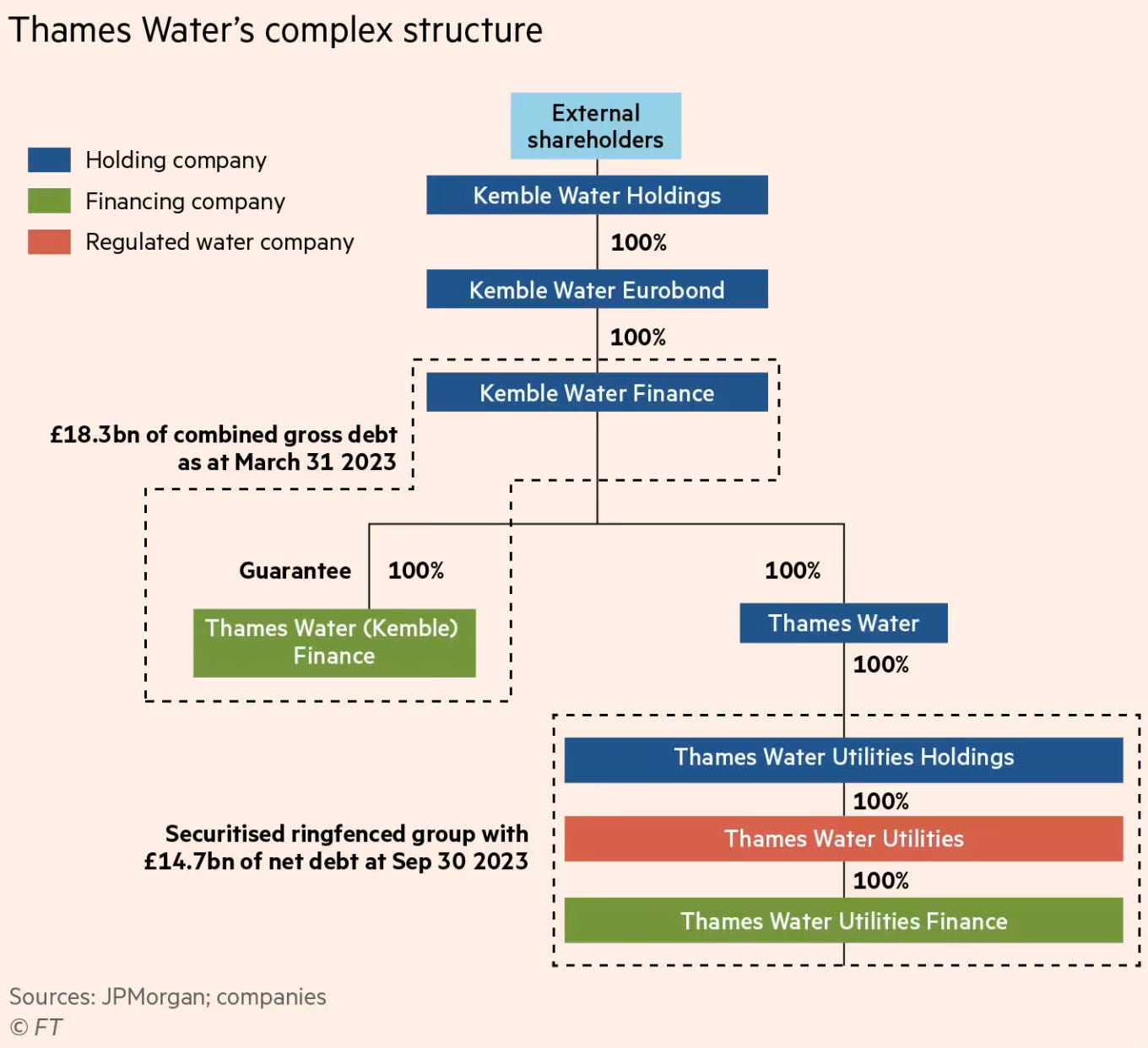

In one more exhibit on the problems with the privatisation of utilities, early this month, Kemble Water Finance, part of the complex financial structure constructed by Macquarie at Thames Water, the largest British water utility serving a quarter of the population and one that provides water to London, announced that it was defaulting on its £400mn bond repayments. This follows its shareholders refusing to make the promised £500mn equity infusion because Ofwat refused to agree to their demands for higher bills and in turn demanded that the shareholders reduce the company’s debt pile.

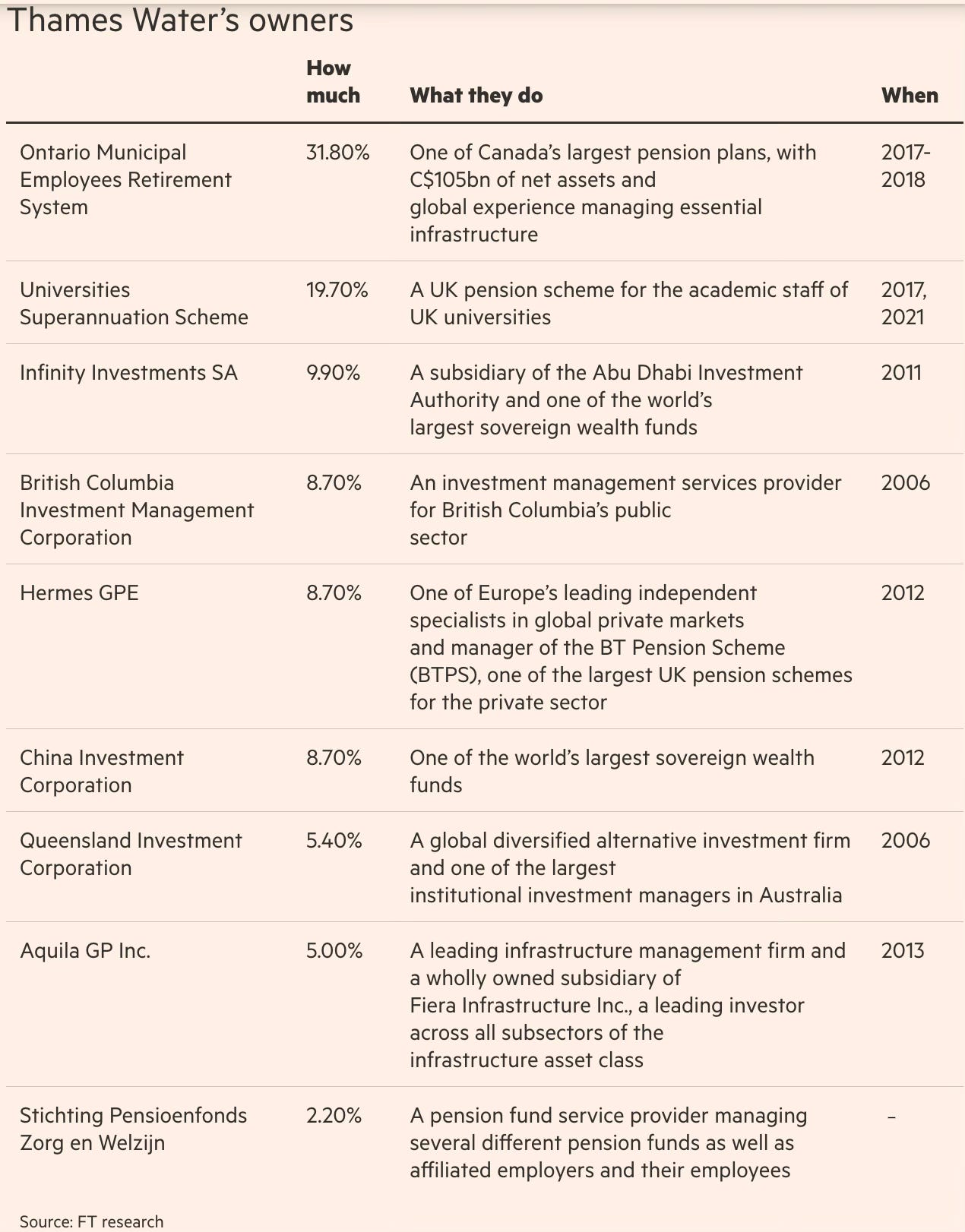

The £14.7bn of debt held by the Thames Water utility companies that sit below Kemble should be unaffected by the default. This debt is in the form of a whole-business securitisation, a structure commonly used to borrow against highly regulated assets with predictable cash flows. But it threatens to wipe out the stakes of Thames Water’s nine shareholders, which include the Chinese and Abu Dhabi sovereign wealth funds as well as Canadian and UK pension funds. Further, Kemble’s £400mn bonds are trading at little over 15 per cent of their face value, indicating debt investors too are set for a near-total wipeout. Most importantly, it raises questions about how Thames Water itself will be able to repay the £14.7bn of debt.

This is the list of Thames Water’s owners.

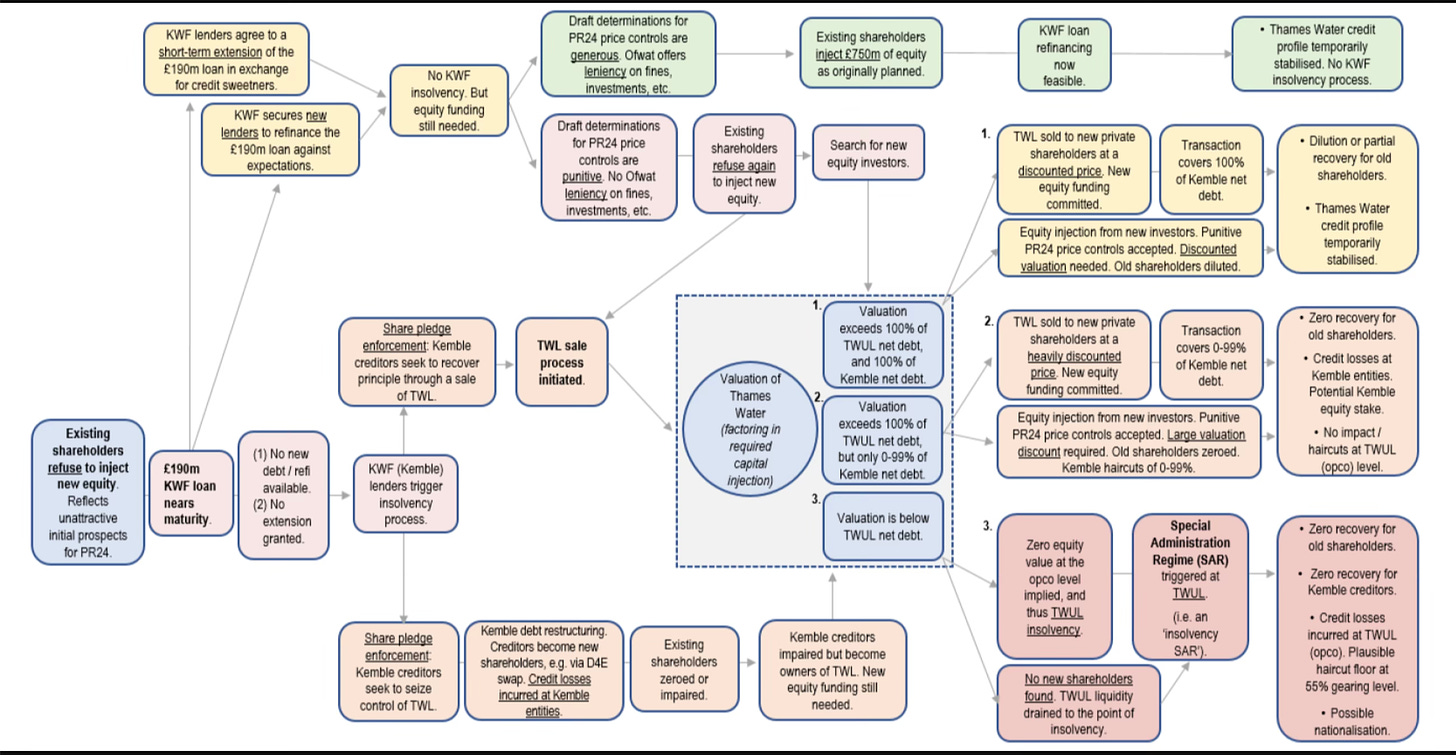

Underlining the complexity of the financing structure, JP Morgan published this outcome-probabilities chart.

The FT article writes about the origins of Kemble’s troubles

The Kemble debt is a legacy of Thames Water’s 2006 buyout by Macquarie, which has drawn scrutiny for the billions of pounds in dividends the firm siphoned off during its decade-long ownership. Macquarie put in place a so-called “whole-business securitisation”, where the utility’s cash flows service different tiers of debt. Kemble, named after a village in the English countryside near the source of the river Thames, allowed the firm to borrow more money. Kemble relies on dividends from Thames Water to pay interest to its bondholders and lenders. However, new rules introduced by Ofwat last year prevent the payment of dividends from the utility if they put the company’s financial resilience at risk. Ofwat opened an investigation into a £37.5mn dividend paid by Thames Water in October last year, with a ruling expected within weeks.

Then there’s also the inflation-indexed nature of the debt, which forms more than half the utility’s debt.

The 2022 annual accounts of parent company Kemble Water Holdings show that the weighted average interest on the group’s £7.7bn of “index-linked debt” soared to 8.1 per cent from just 2.5 per cent the previous year… An “inflation risks sensitivity analysis” — which conceded that the RPI-linked debt only acted as a “partial economic hedge” — showed that a 1 per cent increase in the rate of inflation after 31 March 2022 would dent the group’s profit and equity by £911mn.

The original sin of course lies in the 2006-17 ownership of Thames Water by Macquarie.

When the former prime minister Margaret Thatcher privatised the water monopolies in 1989, she wiped out their debt. Since then, Thames Water’s group borrowings have grown to £18.3bn as the company passed from owner to owner. By 2006, when the Australian asset management firm Macquarie bought Thames Water from the Germany utility group RWE, the water company had £3.4bn in debt. By the time Macquarie sold its final stake in Thames Water in 2017, the company had spent £11bn from customer bills on infrastructure. But far from injecting any new capital in the business — one of the original justifications for privatisation — £2.7bn had been taken out in dividends and £2.2bn in loans, according to research by the Financial Times. Meanwhile, the pension deficit grew from £18mn in 2006 to £380mn in 2017. Thames Water’s debt also increased steeply from £3.4bn in 2007 to £10.8bn at the point of sale.

All this means that in the absence of dividend inflows from Thames Water, Kemble Water Finance is insolvent. With the existing shareholders preferring to take an estimated £5bn loss and cut further losses and not put in any more money, complete equity wipeout and large debt haircuts look inevitable. Any restructuring which does not provide a long-term financing solution for Thames Water, an increasingly difficult prospect, would effectively end up being a return to nationalisation of an asset that was privatised in 1989! A nationalisation should come as no surprise since the latest YouGov polls find that 69% of people believe water companies should be nationalised.

In this context, Frédéric Blanc-Brude points to the problems with using traditional CAPM models to calculate the fair value of investments.

At the end of 2022, a group of large pension plans, including funds from Canada, Japan and the UK, discovered that they had lost a large part of the £5bn investment in Thames Water that they had recorded on their books. This Easter, they learnt that they had probably lost all of it. There is only one way for a water utility serving the capital of a G7 country to lose so much value so fast: it was never worth £5bn to begin with. Yet its owners denied this reality for years. The signs that Thames Water and its parent Kemble Water Finance constituted a high-risk, low-profit business were there all along. The cost of capital in this investment should have been considered quite high (and increasing over the years) and its value much lower…

Many investors in private assets — and in this case the water sector regulator, Ofwat, too — rely on the “capital asset pricing model” (CAPM) to estimate a cost of capital and the value of the business (and for Ofwat the allowed level of water tariffs)…. Today, CAPM remains the most commonly used framework for estimating the value of private investments like infrastructure companies. Yet the scientific community has known for more than 30 years that CAPM, while one of the foundations of the field of academic finance, is wrong… The inevitable conclusion from all this is that the reported values of private investments held by institutional investors and their managers today are very likely to diverge significantly from their true market value, and do not represent the level of risk taken or the liquidation value of these assets. This is how investors in Thames Water saw their investment go from £5bn to zero in a few months — they were blindsided by bad models and bad data…

There is a better way. Applied financial research and data availability about private investments have made significant progress since CAPM was developed in the 1960s. It is time for investors in private companies like Thames Water to take a more scientific view of asset pricing. They need proper measures of risk for the private asset classes to which they now allocate large amounts, and of the value of the assets they hold.

The point that Blanc-Brude makes is very important. The reluctance of the market to use empirical evidence on important decisions like valuation, especially given the stakes involved, is baffling. There’s such a rich repository of data about infrastructure projects from across the world that it must be possible to look at the realised outcomes from projects across different segments of the sector and make informed, evidence-based assumptions of cost of capital, returns on equity etc. Why use theoretical models with limited practical relevance when there’s good historical data available?

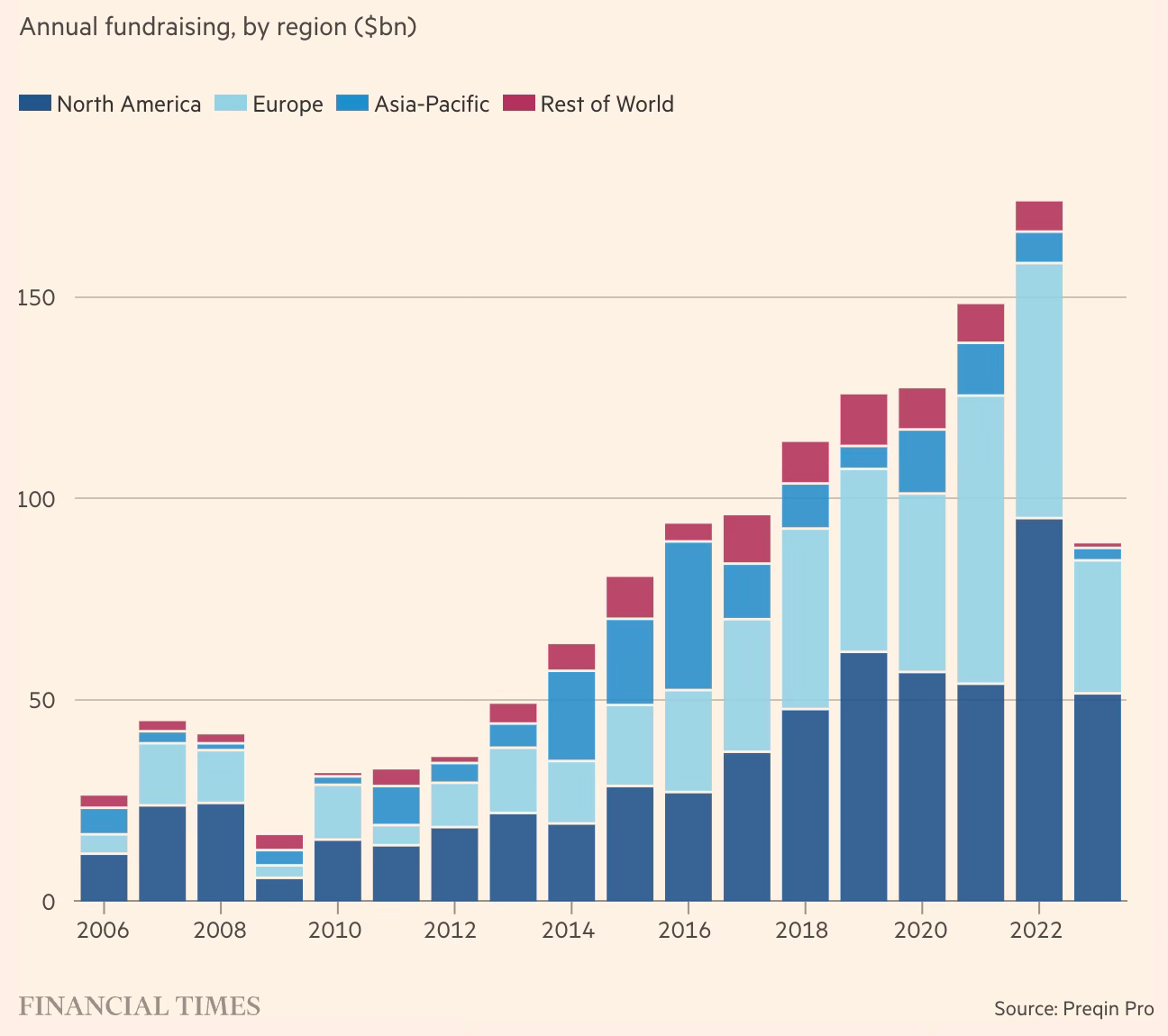

A thing that has intrigued me is why alternative investment funds (AIFs), which typically chase high-risk and high-return investment options, find infrastructure as an attractive asset class. Infrastructure is mostly regulated and therefore comes with low but stable returns but for a long tenor. It’s for this reason that traditionally pension funds and insurers, which look at very long investment horizons, find infrastructure an ideal investment option. Its stable returns and long-tenor are high value for them.

For fund managers in AIFs like private equity, the infrastructure sector’s attractions can therefore come only from the perspective of asset diversification and not returns maximisation. But this is theory. In reality, private equity investors who are now piling into infrastructure feel that they can make high returns from infrastructure. They see Macquarie’s track record of extracting high returns from infrastructure, none more high-profile than Thames Water itself, as evidence.

But, as I have blogged and written extensively over the years, these returns can come only at the cost of the project itself. It can come only from asset stripping by loading the company with debt, paying out large dividends, skimping investments, not paying employees pension funds, and so on. The shorter cycle of a PE investment compared to the life cycle of an infrastructure asset means that PE investors can strip assets from the project entity. This is especially true in the case of assets that are newly concessioned out or privatised - the first set of PE investors have a strong perverse incentive to squeeze the balance sheet of the project entity, pay themselves handsome dividends, and exit. Even if they don’t exit and get stripped of their equity after a few years, they would have made enough for themselves and their investors.

Fundamentally, as I blogged here, infrastructure finance 3.0, which PE kind of investors represent, is about separating ownership from the operations and the life cycle of the asset. Ownership gets parcelled into tranches and is transferred from investor to investor. There’s limited skin in the game for these investors in the asset’s long-term prospects. They are concerned only about the asset being a going concern till they are around and can find another investor who too would have similar incentives.

There are two big losers in such situations. One, creditors to infrastructure assets owned by PE firms (who indulge in such asset stripping) can be left holding a bankrupt entity and are forced to take large haircuts. Two, given the monopoly provider of an essential service nature of such assets, governments cannot allow these assets to fall into liquidation. They will have to step in to facilitate restructuring and find new owners who can operate the asset or take it over and run itself. In either case, taxpayers are on the hook.

Truth be told, PE investments in infrastructure are mainly aimed at segments like data centres, telecommunications, and natural gas where there are enough opportunities for higher returns.

Three takeaways from this. One, policymakers should be careful about what they wish when they court private investors like AIF in infrastructure sectors. There’s a strong case for designing bid documents that are explicit about the expectations of investors from such investments. Bid documents should pre-empt asset-stripping possibilities by mandating clear, salient, strict, and public disclosures of relevant information. Two, regulators must be vigilant in monitoring PE (and any other private) investments in infrastructure sectors for the various asset-stripping practices. Three, creditors should have supervisory mechanisms to watch the emerging financials of their borrowers.

No comments:

Post a Comment