Econ 101 teaches us that the combination of comparative advantage and free market would result in efficient and mutually beneficial outcomes. The problem is that this is correct, but only in theory. The reality, while always different, is made far worse by the domineering presence of China with its capture-global-markets industrial policy.

Across industries, the Chinese have established global market dominance through its combination of economy-wide (cheap land, labour, and capital) and industry-specific (cheap inputs, credit, and other incentives) subsidies, and tariff and non-tariff barriers on foreign competition. In this journey, the state-owned entities have been complemented with privately owned but strictly government-guided entities to pursue broad national economic, industrial, and strategic goals.

The strategy is now clear and has been repeated across industries. It goes something like below:

1. Declare certain industries as national strategic priorities, and provide them long-term industrial policy support. Such support would include both economy-wide and industry-specific incentives and subsidies.

2. Encourage local firms to iterate and test products and technologies and deploy them in the domestic market where foreign competition is walled off. Alternatively, establish favourable partnerships and joint ventures with foreign companies underpinned by strict technology transfer requirements.

3. Incentivise export competition so that only the most competitive succeed and the weak fail.

4. Leverage the economies of scale (from both domestic consumption and exports) to drive mega-scale manufacturing.

5. Use foreign policy to creatively and egregiously strike deals with national governments to funnel minerals and other inputs required for the industry.

6. Establish firm political control over all companies, including foreign-owned ones, through the Communist Party membership on their Boards.

This means that the playing field in each industry becomes heavily skewed in favour of Chinese firms and also against foreign firms. It becomes difficult, almost impossible, for foreign firms to be competitive with Chinese firms. In most industries, the losers are firms from other developing countries which are competing in the same markets with Chinese firms.

The results are damaging in the long run for the importers. Their domestic industry is destroyed by cheap Chinese imports. The domestic firms are made uncompetitive. The tightly politically controlled nature of Chinese enterprises, public and private, means that there’s limited technology transfer and other beneficial spill-overs in the host countries. Even when these companies establish local factories, they fly in Chinese workers and managers to manage all critical activities. Then there’s the deeply problematic risk to national security from the likelihood of Beijing weaponising its dominance to suit its national interests.

In the nineties and noughties, this playbook was adopted in textiles, footwear, furniture, and consumer electronics. Since then it was expanded to cover thermal, solar and wind power generation, metro railways, construction equipment, shipbuilding etc. In recent times, the strategy has been embraced in lithium batteries, electric vehicles and automobiles in general. The country is now pushing hard on semiconductor chips, though with limited success till date.

Rana Faroohar in FT has an excellent long read that chronicles the decline of the US shipbuilding industry. She points to the national security and economic concerns that it raises, and the trade tensions that Chinese dominance engenders.

The industry has come to the fore as the US labour unions have filed a Section 301 petition to the US Government accusing China of distorting global markets in the maritime, logistics, and shipbuilding sectors through "unreasonable and discriminatory acts, policies, and practices".

The petition, which the US government now has 45 days to respond to, seeks a variety of penalties and remedies to level the global playing field in shipbuilding and stimulate demand for commercial vessels built in the US. These include port fees on Chinese-built ships docking at US ports, and the creation of a Shipbuilding Revitalisation Fund to help the domestic industry and its workers. A case that might appear focused on one industry in fact has dramatic global implications. Not only does it have the potential to reignite the US-China trade conflict, but it will also increase the focus on China’s growing military might and the massive commercial shipping industry that underpins it. At the same time, it raises questions about America’s ability and even willingness to reindustrialise in strategic sectors... Finally, it’s a window into whether the US has the ability to continue to play its traditional post-second world war security role, which includes policing global shipping lanes and securing the South China Seas for commercial transport, at a time when it no longer has the industrial capacity and workforce to build its own ships.

The trajectory of the Chinese shipbuilding industry has followed other industries which were Beijing’s national priorities.

In 2006, it became one of the seven strategic industries over which state-owned enterprises should maintain control. In 2015, as part of the Made in China 2025 plan, Beijing identified shipbuilding as one of the ten priority sectors in which China would seek to dominate global commerce by 2025. Since then, the Chinese shipbuilding industry has enjoyed policy loans from state-owned banks, equity infusions and debt-for-equity swaps, below market rate steel inputs, tax preferences and grants from export agencies, as well as protection from foreign ownership.

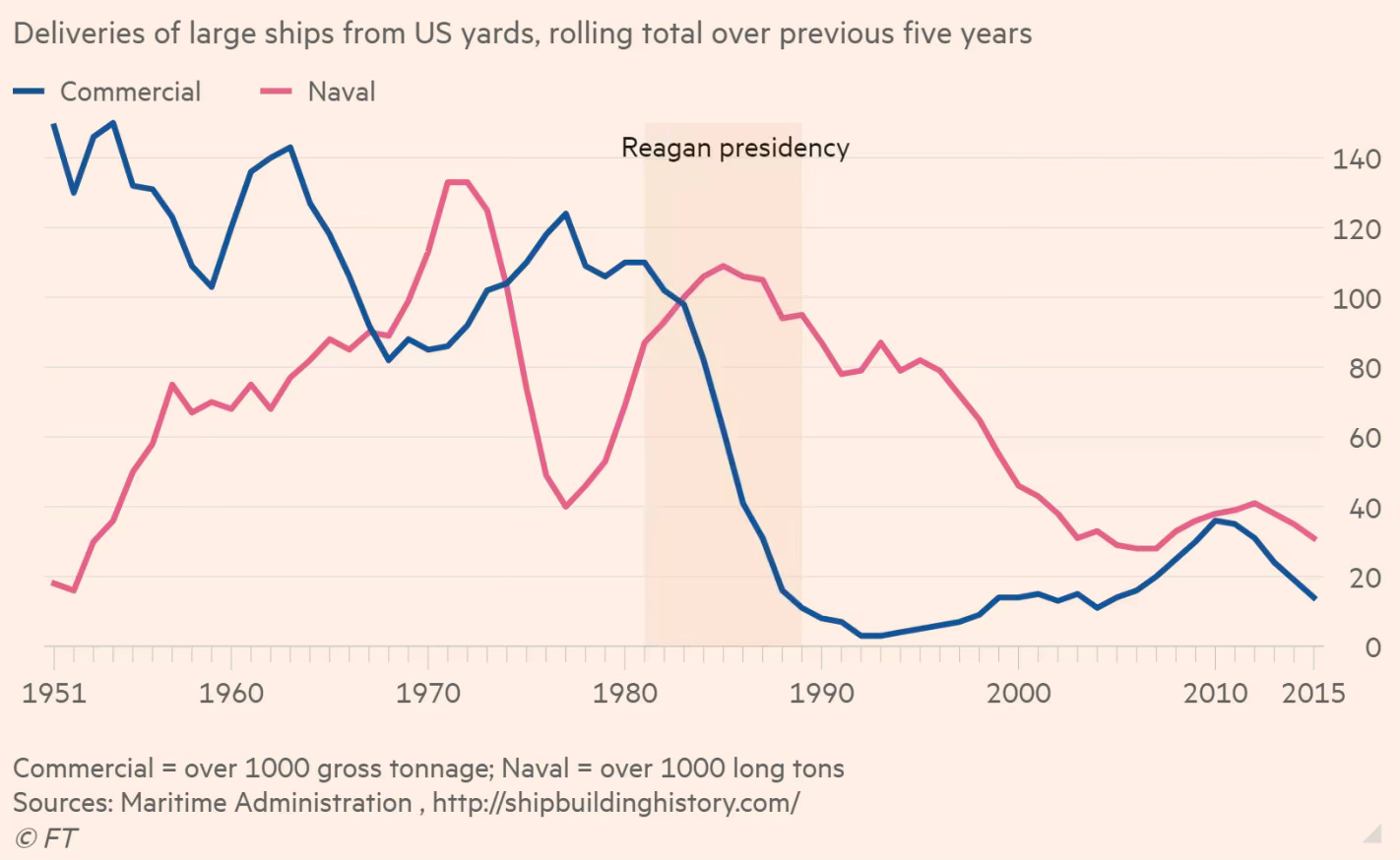

The decline of American shipbuilding industry has been dramatic and mirrors trends elsewhere in manufacturing.

In 1975, the US shipbuilding industry was ranked number one in terms of global capacity, with more than 70 commercial ships on order for production domestically. Nearly 50 years later, the US now produces less than 1 per cent of the world’s commercial vessels, falling to 19th place globally. China meanwhile has tripled its production relative to the US over the past two decades, producing over 1,000 ocean-going vessels last year, versus America’s 10.

This trajectory of decline of the US shipbuilding industry is emblematic of others where the Chinese have now established dominance,

The shrinkage in the US shipbuilding industry is a result of several factors, say US shipbuilding experts, starting in the 1980s, when most government subsidies for shipbuilding were pulled, given that they were antithetical to the free market economics embraced by the Reagan administration... Much of the raw materials and components needed to produce new ships are no longer available in the US, thanks to the shrinking and outsourcing of the American manufacturing base, according to defence officials and unions. That’s a problem common in many industries, not just shipbuilding. Meanwhile, as a “just in time” production approach was employed over the past few decades, US contractors were discouraged from having excess capacity that might be needed in the event of a supply chain disruption, natural disaster, or security emergency. This, along with consolidation in the industry and the rise of cheaper ships produced in Japan, South Korea and most recently China, has led to lowered investment in things like technology, factory equipment and training for US workers. The result has been an overall decline in competitiveness and capacity in US shipbuilding yards, according to navy and union officials, as well as some labour economists.

The article makes an important point about the incentive mismatch between the businesses and their executives, and the employees and the local communities.

USW president David McCall, who represents workers making everything from steel and engines to paints, cables and other products used in ships, notes that US steel mills are running at about 70 per cent capacity around the country… Indeed, it’s telling that the steelworkers’ union actually negotiates things like capital investment into the factories that support industries like shipbuilding as part of their own collective bargaining efforts. In a globalised market, the workers have more incentive to seek investment in their industries than large public corporations that can place jobs or investments anywhere, according to McCall. “The CEOs that run these companies may leave after a few years, with golden parachutes, but we work in our communities for decades. We have to think about long-term security for workers,” says McCall.

This is a complaint that many on the labour left, and increasingly some on the political right too in the US, have made, particularly as it relates to industries in crucial or strategic sectors. With the breakdown of the US-led system of free market policies and institutions known as the Washington consensus, the supply chain vulnerabilities exposed by Covid-19 and wars in Ukraine and the Middle East, and the increase in economic and political tensions between China and the West, business as usual is increasingly challenged… Rebuilding a workforce and factories from scratch takes time, and achieving the scale and high-speed iteration crucial to the cost-effectiveness and productivity of operations can take further years or decades of investment… a viable commercial shipping industry and national security aren’t discrete problems, but are intricately connected.

The rise of Chinese shipbuilding and port operating companies poses serious strategic concerns and national security risks

More than 90 per cent of military equipment, supplies and fuel travels by sea, according to the 301 complaint, the vast majority on contracted commercial cargo vessels. All of these are made overseas, including some in China... The complaint says, “Chinese companies — primarily state-owned companies — have become leaders in financing, building, operating and owning port terminals around the world.” According to research by Isaac B Kardon, an assistant professor at the China Maritime Studies Institute at the US Naval War College, and Wendy Leutert, an assistant professor at Indiana University, Chinese firms own or operate one or more terminals at 96 foreign ports, 36 of which are among the world’s top one hundred by container throughput.“Another 25 of these top 100 are on the Chinese mainland, establishing a PRC nexus for some 61 per cent of the world’s leading container ports,” they wrote in a 2022 article in International Security. China also makes much of the equipment used in the industry. A Chinese state-owned company, ZPMC, provides 70 per cent of the world’s cargo cranes. This level of control over global logistics and supply chains offers clear economic and security advantages, and reflect decades of policy decisions taken by both the US and China... As the secretary of the navy, Carlos del Toro, put it in a speech at the Harvard Kennedy School last September, “History proves that, in the long run, there has never been a great naval power that wasn’t also a maritime power — a commercial shipbuilding and global shipping power.”

The article points to other serious security concerns from Chinese actions in the shipbuilding industry.

China has, over the past several years, rolled out the pre-eminent global logistical supply chain platform, Logink, which it is giving for free to various ports around the world. The worry on the part of the US administration, as well as many in the labour and defence communities, is that this could give Beijing a window into global supply chains — both commercial and military — that would be both a competitive issue and a national security concern. As a recent Department of Transportation Maritime Administration warning put it, “Logink is a single-window logistics management platform that aggregates logistics data from various sources, including domestic and foreign ports, foreign logistics networks, shippers, shipping companies, other public databases, and hundreds of thousands of users in the PRC.” The warning further states that “the PRC government is promoting logistics data standards that support Logink’s widespread use, and Logink’s installation and utilisation in critical port infrastructure very likely provides the PRC access to and/or collection of sensitive logistics data”.

Faroohar’s conclusion is apt

The case calls into question the role of industrial policy in fair and secure market crafting, as well as the need for a new global trading paradigm — one that accounts for state-run systems, and acknowledges the challenges that free market economies and public corporations governed by short-term, shareholder concerns have competing with them.

Keith Bradsher in The NYT has another article on how China established global dominance in solar energy.

China unleashed the full might of its solar energy industry last year. It installed more solar panels than the United States has in its history. It cut the wholesale price of panels it sells by nearly half. And its exports of fully assembled solar panels climbed 38 percent while its exports of key components almost doubled… With China’s economy stumbling, the ramped-up spending on renewable energy, mainly solar, is a cornerstone of a big bet on emerging technologies. China’s leaders say that a “new trio” of industries — solar panels, electric cars and lithium batteries — has replaced an “old trio” of clothing, furniture and appliances… China produces practically all of the world’s equipment for making solar panels, and almost all of the supply of every component of solar panels, from wafers to special glass.

The market destroying dynamics of cheap Chinese imports.

The alarm in Europe is particularly great. Officials are bitter that a dozen years ago, China subsidized its factories to make solar panels while European governments offered subsidies to buy panels made anywhere. That led to an explosion of consumer purchases from China that hurt Europe’s solar industry. A wave of bankruptcies swept the European industry, leaving the continent largely dependent on Chinese products…

China’s cost advantage is formidable. A research unit of the European Commission calculated in a report in January that Chinese companies could make solar panels for 16 to 18.9 cents per watt of generating capacity. By contrast, it cost European companies 24.3 to 30 cents per watt, and American companies about 28 cents. The difference partly reflects lower wages in China. Chinese cities have also provided land for solar panel factories at a fraction of market prices. State-owned banks have lent heavily at low interest rates even though solar companies have lost money and some went bankrupt. And Chinese companies have figured out how to build and equip factories inexpensively. Low electricity prices in China make a big difference. Manufacturing the main raw material for solar panels, polysilicon, requires huge amounts of energy. Solar panels typically must generate electricity for at least seven months to recoup the electricity that was needed to make them.

The trajectory of the evolution of the Chinese industrial base in solar sounds familiar.

As recently as 2010, Chinese producers of solar panels relied mainly on imported equipment, and faced long and costly delays if anything broke down… In 2010, Applied Materials, a Silicon Valley company, built two extensive labs in Xi’an, the city in western China famous for terra-cotta warriors. Each lab was the size of two football fields. They were intended to do final testing for assembly lines with robots that could churn out solar panels with practically no human labor. But within several years, Chinese companies had figured out how to do it themselves. Applied Materials considerably cut back its production of solar panel tooling and focused on making similar equipment that makes semiconductors.

The shipbuilding and solar industries are a sobering reminder if one were needed after so many such examples globally, that the so-called free markets are (in addition to several other factors) deeply distorted by domestic policies (especially in China). Large countries therefore need to have domestic industrial bases in all the major sectors, especially those with strong national security interests. Foregoing the benefits from trading with trade distorters like China may just be the cost of maintaining economic stability and national security. It’s more than a fair price to pay.

No comments:

Post a Comment