This post will discuss a framework for thinking about knowledge acquisition and information processing in the context of public policy.

I blogged here pointing to two kinds of knowledge (even information) - learnt and experiential. The former is acquired through structured settings like classrooms, readings, and listening. In any domain, such knowledge contains concepts, theories, techniques and toolkits. The latter is accumulated over the lived life and lived career of an individual. It’s a huge series of experiential data points. The former is largely theoretical and objective, whereas the latter is purely personal and therefore subjective.

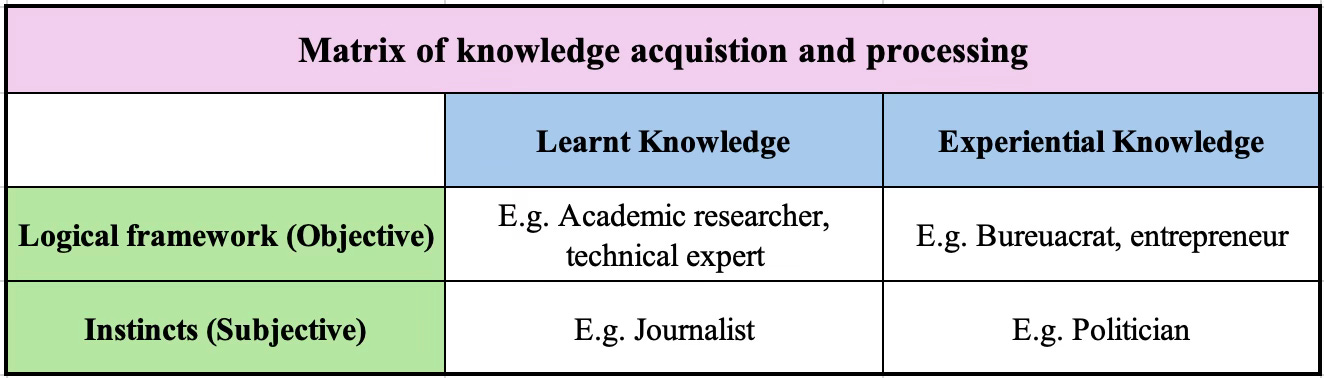

Similarly, we can think of two pathways of information processing - logical and judgmental. In the former, an individual uses some logical framework and in the latter his or her instincts to process the information and make an inference or decision. Again, as earlier, the former is objective, whereas the latter is necessarily subjective (and therefore personal). Experiential knowledge is accumulated by living and doing. Instincts are a function of one’s values, preferences, and experiences.

The table above captures the framework with some illustrative examples. The examples are only indicative representations of the category of people illustrated. As can be seen, each category of people has its unique comparative advantage. But while learnt knowledge can be acquired through some structured process, experiential knowledge accumulation depends on one’s professional role and the experience gathered.

This means that, for example, outsiders to the public policy practice like an academic researcher or a technical expert will generally be constrained by their deficient experiential knowledge. On similar lines, though bureaucrats have rich experience, they struggle with their technical expertise and analytical frameworks.

The ultimate objective is to exercise good judgment. Good judgment is nothing but wisdom (in that domain). A person who can exercise good judgment can be considered wise.

Good judgment can be exercised when both knowledge and knowledge processing pathways are combined. This person uses logical frameworks to process his or her learnt and experiential knowledge and then applies the filter of experience to make judgments about the issue, idea, event, or situation.

In other words, a person can improve judgment about something by reading/listening/travelling more and through more personal experiences, and bringing all of them together in a thoughtful manner (this can also help depersonalise the experiential aspect, though only to some extent). The volume and diversity (understanding of different perspectives and opinions) of experiential data points used to make the judgment are important to make good judgments. It’s therefore often said that people with rich practical experience are able to exercise good judgment.

There’s a limit to how much learnt knowledge and smart reasoning can help improve judgment at the margins. Instead, conditional on a broadly similar understanding of learnt knowledge, the quality of judgment is a function of experience.

All this is important since the formation of opinions on most public policy issues, where there's no one single correct answer, is a matter of judgment. It’s easy to conflate logic and judgment, and wrongly believe that what are purely personal judgments are instead logical (and therefore universal) answers. Just as expert opinion is skewed towards concepts and theories and is unfiltered by experience, bureaucratic opinion generally tends to be blinkered by experience alone.

The point about judgment is very important, especially on wicked problems of the kind that public policy throws up. High-stakes and high-level public policy decision-making are invariably about exercising judgment. They are done best when some institutional structures and incentives bring together several strands of thinking and inputs from multiple sources that combine technical expertise and experience.

Unfortunately, as Albert Hirschman has so eloquently articulated, it’s hard to exercise good judgment. It’s therefore the binding constraint in development.

No comments:

Post a Comment