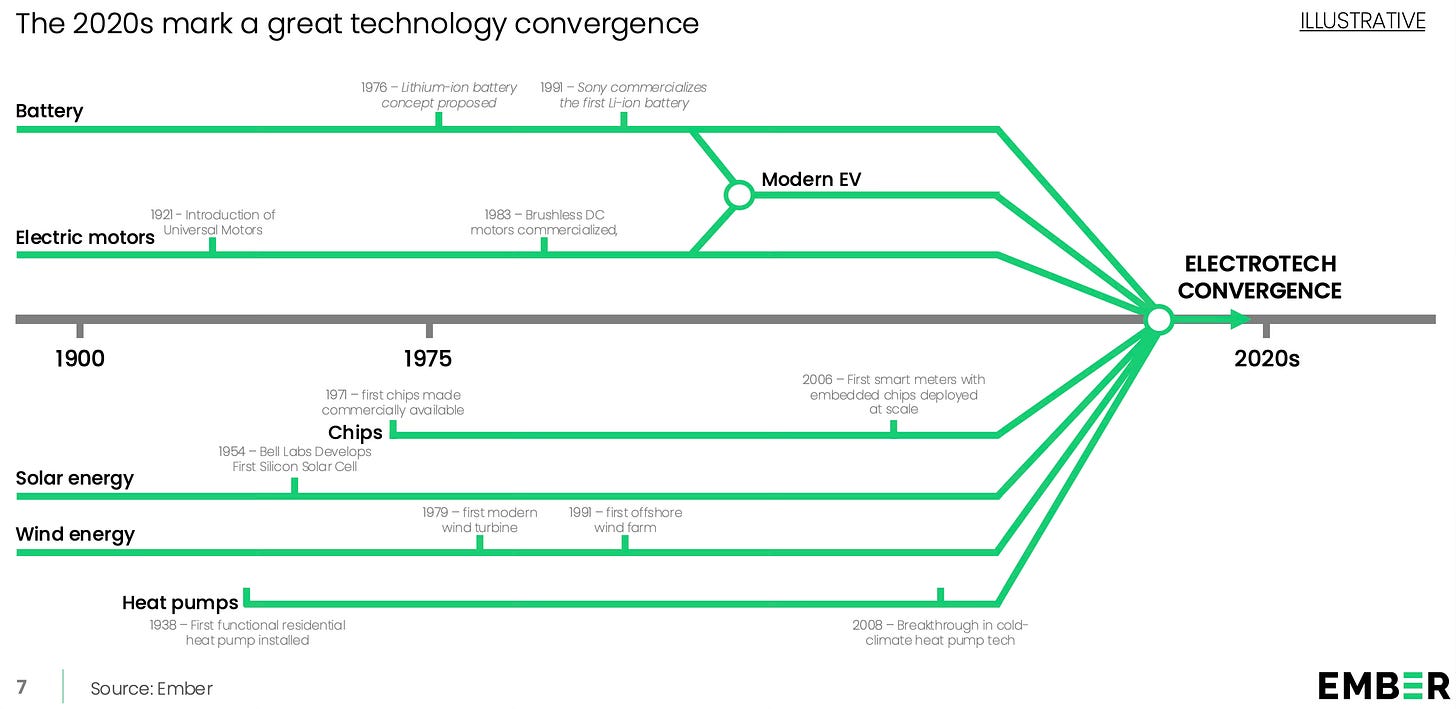

This post tries to document in brief and graphically the emerging electro-industrial stack that has the potential to transform the physical world just as digital technologies have done elsewhere.

This post draws mainly from four sources - Noah Smith’s introduction to the Electric Age, a succinct primer on the electro-industrial stack by Ryan McEntush on a16z, a brilliant 40,000-word comprehensive essay by Packy McCormick and Sam D’Amico, and an excellent graphical distillation of the electrotech revolution by Ember.

McEntush describes these technologies as the “bridge between software and the physical world… enabling machines to behave like software: minerals and metals processed into advanced components, energy stored in batteries, electrons channeled by power electronics, force delivered by motors and actuators, all orchestrated by software running on high-performance compute.”

Noah Smith has a good summary of what’s driving the electrotech revolution:

Basically, these three things allow electric motors to replace combustion engines (and steam boilers) over a wide variety of applications. Batteries make it possible to store and transport electrical energy very compactly and extract that energy very quickly. Rare-earth motors make it possible to use electrical energy to create very strong torques — for example, the torque that turns the axles of a Tesla. And power electronics make it possible to exert fine control over large amounts of electric power — stopping and starting it, rerouting it, repurposing it for different uses, and so on. With these three technologies, combustion’s main advantages vanish in many domains. Whether it’s cars, drones, robots, or household appliances, electric technology now has both the power and the portability that only combustion technology used to enjoy.

Thanks to low-cost, high-energy density batteries, we can now store, move, modulate, and deliver electricity efficiently, powering everything from data centers to drones. There are four parts to what McCormick and D’Amico call the electrotech stack - batteries, power electronics, motors and actuators, and a compute layer. McEntush describes the importance of power electronics.

Power electronics are the hidden nervous system of modern machines. At their core are power semiconductors which, unlike logic chips that process information, manage energy itself — converting, inverting, and regulating flows between sources and loads. Historically, power systems relied on slow silicon switches, steel-core transformers, and bulky analog controls. At high voltage and frequency those approaches are at their limits. Wide-bandgap devices — like silicon carbide (SiC) and gallium nitride (GaN) — switch faster, withstand higher temperatures, and enable precise digital control. This software-driven, solid-state (no moving parts) foundation stitches together the electro-industrial stack… Scaling WBG power electronics is also critical to easing the grid’s growing infrastructure bottlenecks… the way forward is solid-state transformers built with domestically produced WBG power electronics… Future systems will require vast amounts of precisely managed power; delivering it will depend on solid-state electronics under digital control.

And that of motors and actuators

Motors and actuators convert electrical energy into mechanical motion, like in a drone motor or an industrial robot arm. Today’s performance leader is the brushless permanent-magnet synchronous motor (PMSM) using NdFeB magnets, prized for torque density, efficiency, and compactness. But that advantage comes with a strategic cost: dependence on rare earths. Alternatives for motion systems span both motor design and actuation type, each with trade-offs… Actuation choices are also evolving. Flight surfaces, reclining seats, missile fins, landing gear, and industrial end-effectors are shifting from old-school hydraulics to electromechanical systems for lower weight, higher reliability, and precise digital control… The market is testing these across applications… Small gains in motor and actuator efficiency compound across the stack, and as general-purpose robotics scale, this industrial “muscle” will move larger fractions of GDP.

Finally, the compute layer is no less demanding.

The compute layer converts electrical energy into intelligence, controlling everything from autonomous vehicles to advanced weapon systems and industrial robots. Today’s performance leader is 2 to 4 nm-class logic — most often, GPUs designed by Nvidia and fabricated by TSMC… Compute extends beyond the GPU alone; advanced packaging now sets performance limits as much as transistor scaling. System design has expanded from single chips to whole machines, like co-optimizing die, memory, and interconnects alongside rack-level power delivery and cooling. Just as important, software frameworks, compilers, kernels, and drivers map models onto this topology, manage communication and memory, and orchestrate performance across infrastructure. Chinese firms lead in scale for mature nodes and low-cost packaging; the West leads in EDA, lithography, and software ecosystems, but still lacks true leading-edge manufacturing capacity outside Taiwan.

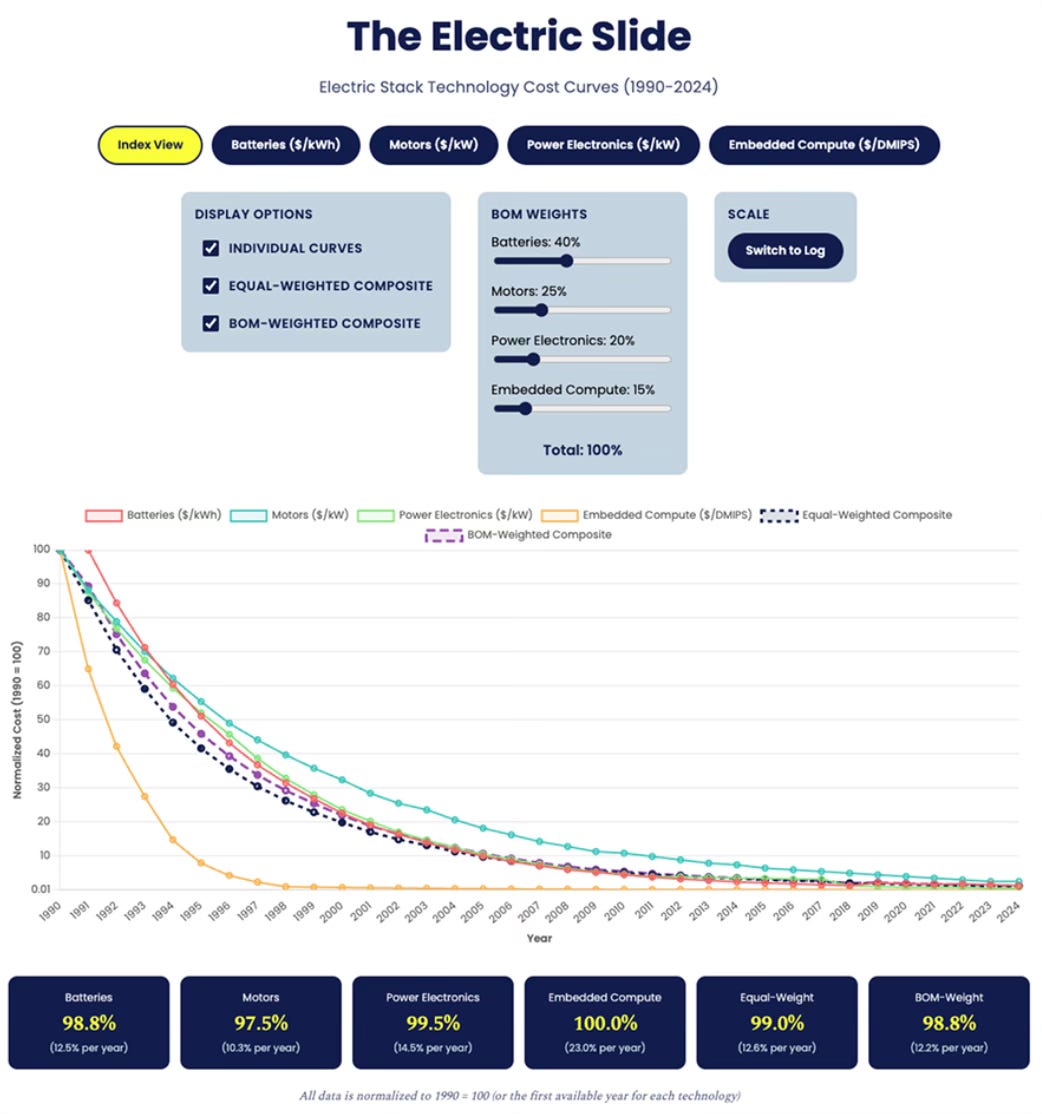

This graphic captures the composition and evolution of the four parts of the electro-tech stack.

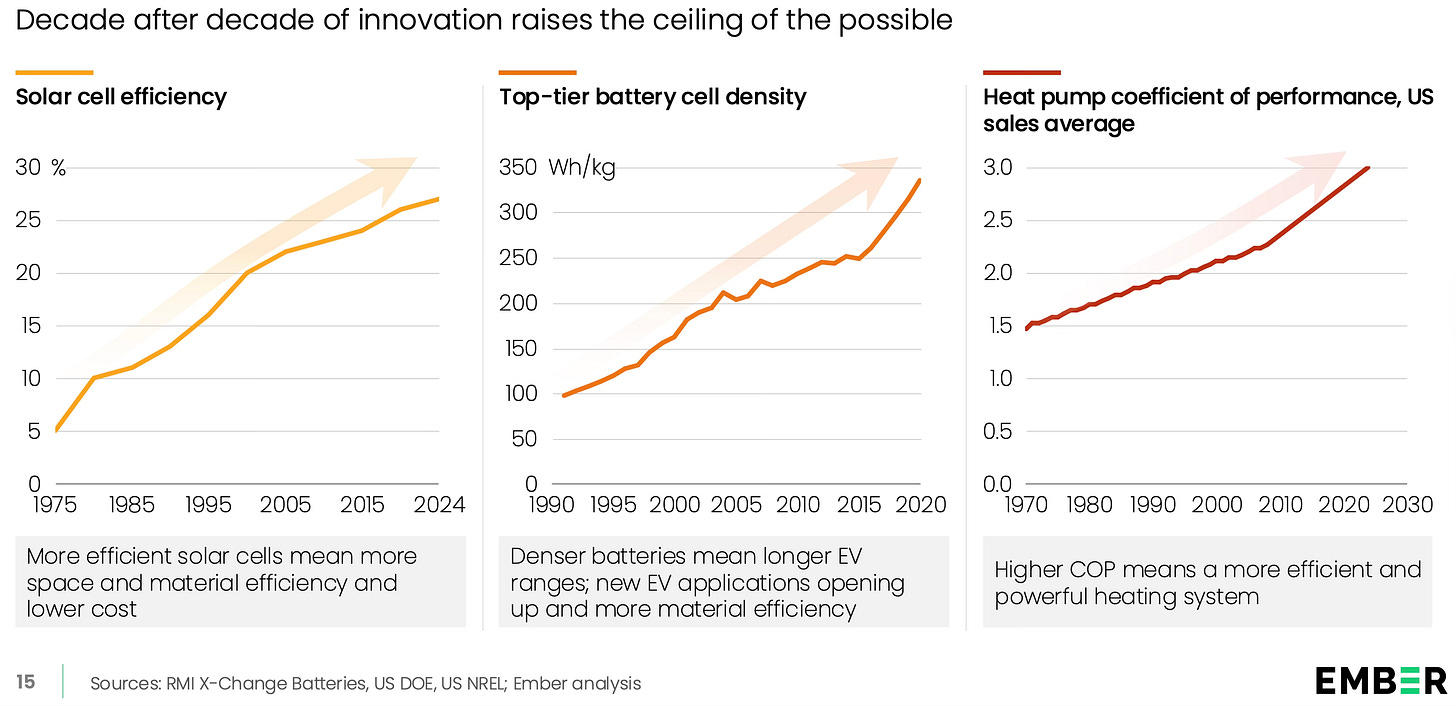

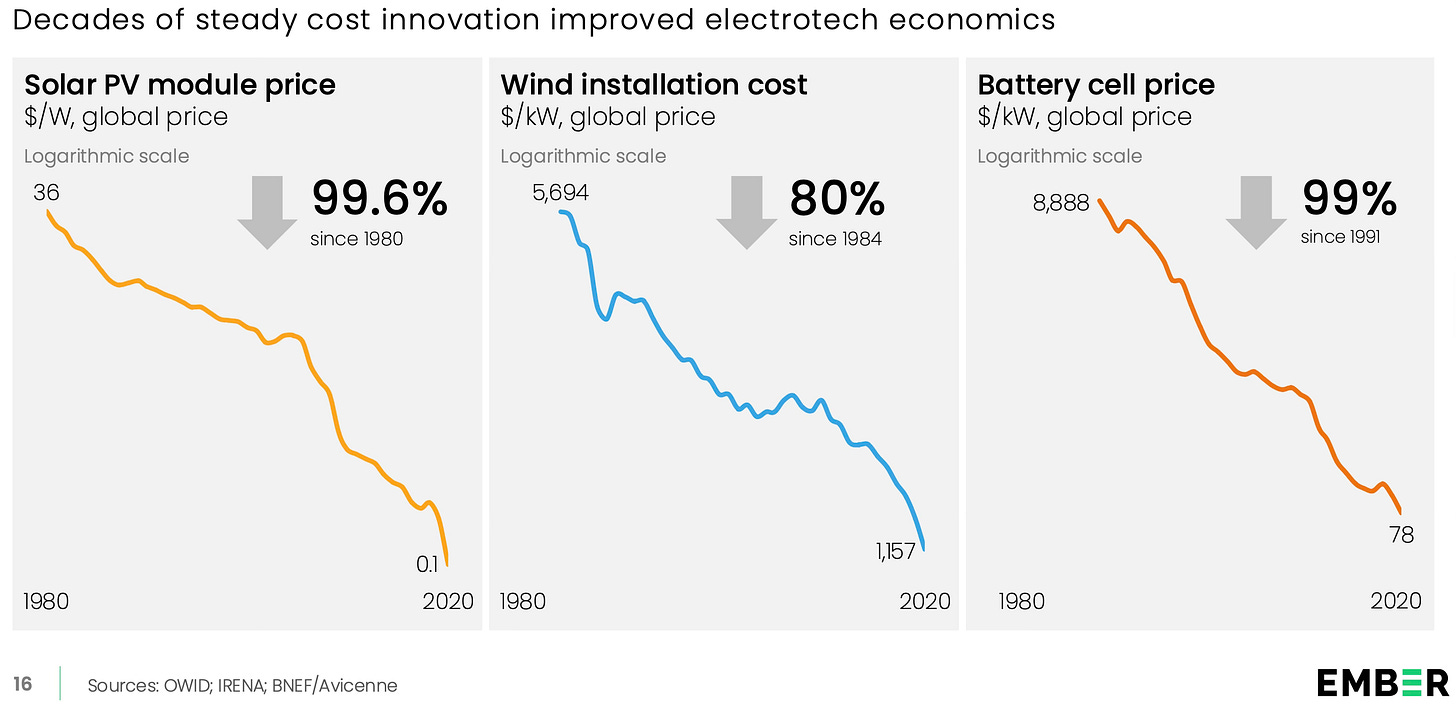

The revolution in electrotechnologies has been driven by innovations that have dramatically increased performance outcomes…

… while also equally dramatically lowering costs…

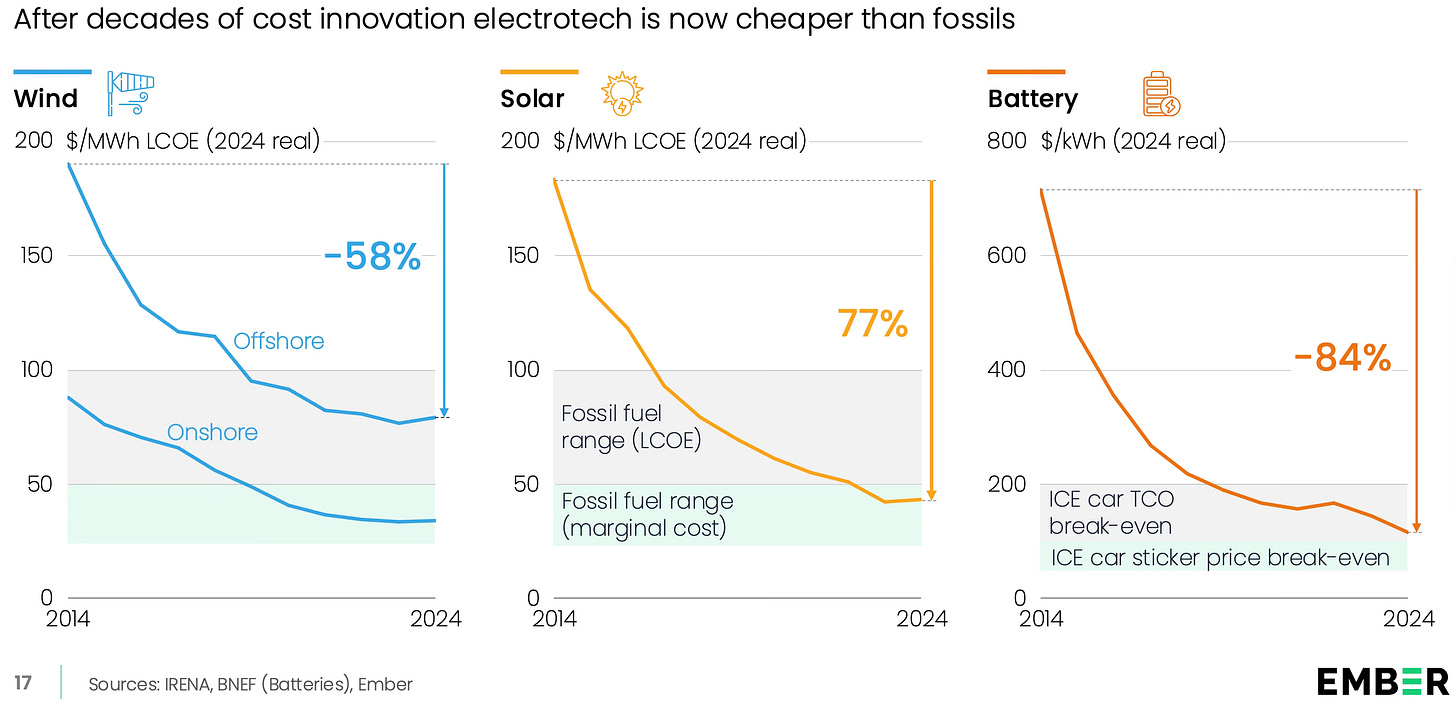

… and become competitive enough with existing technologies.

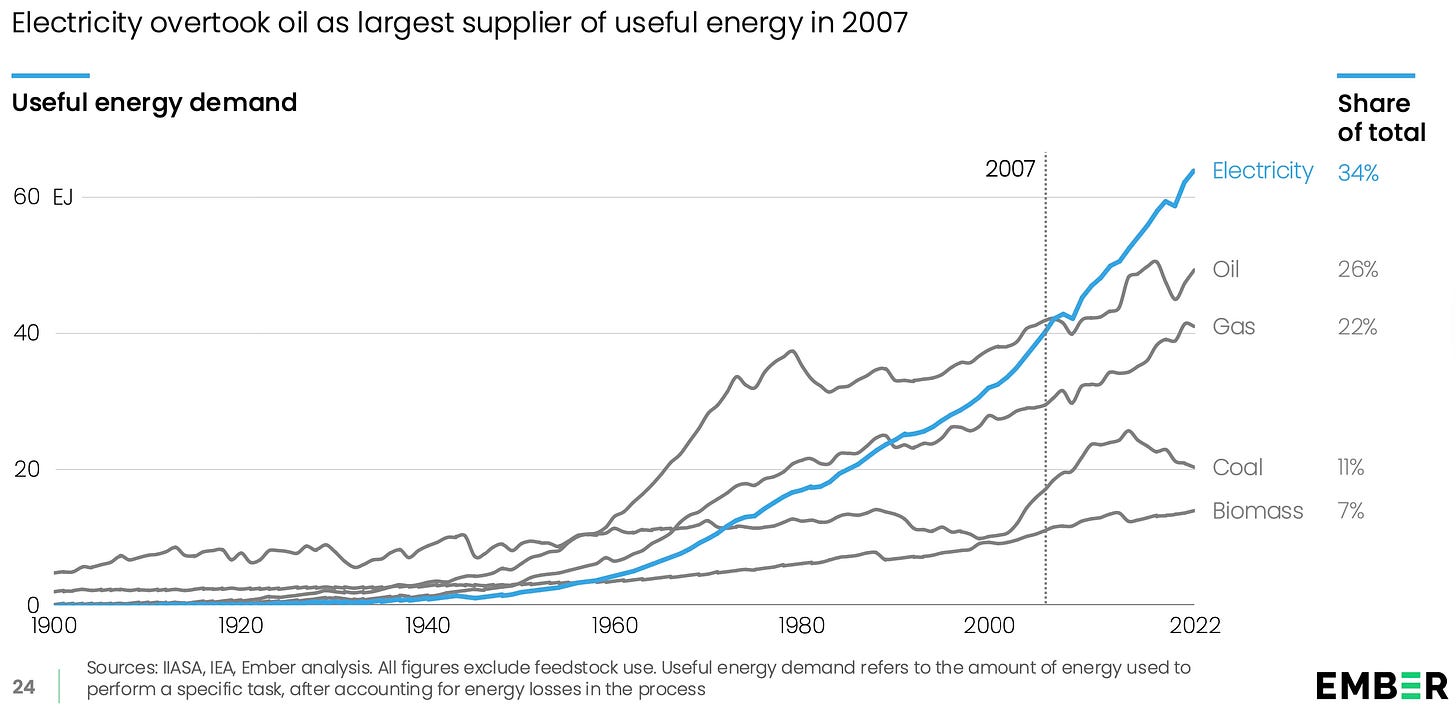

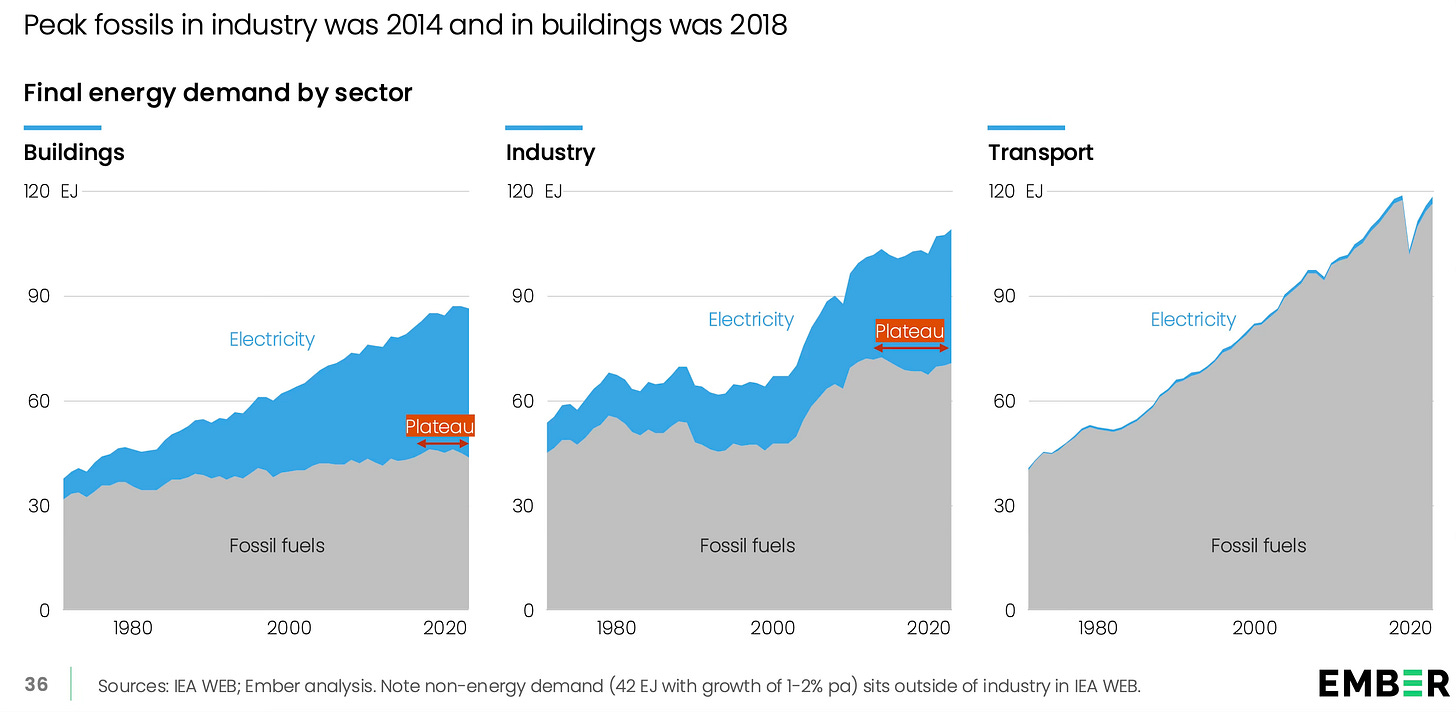

The result of all this is that electricity has become the largest source of energy…

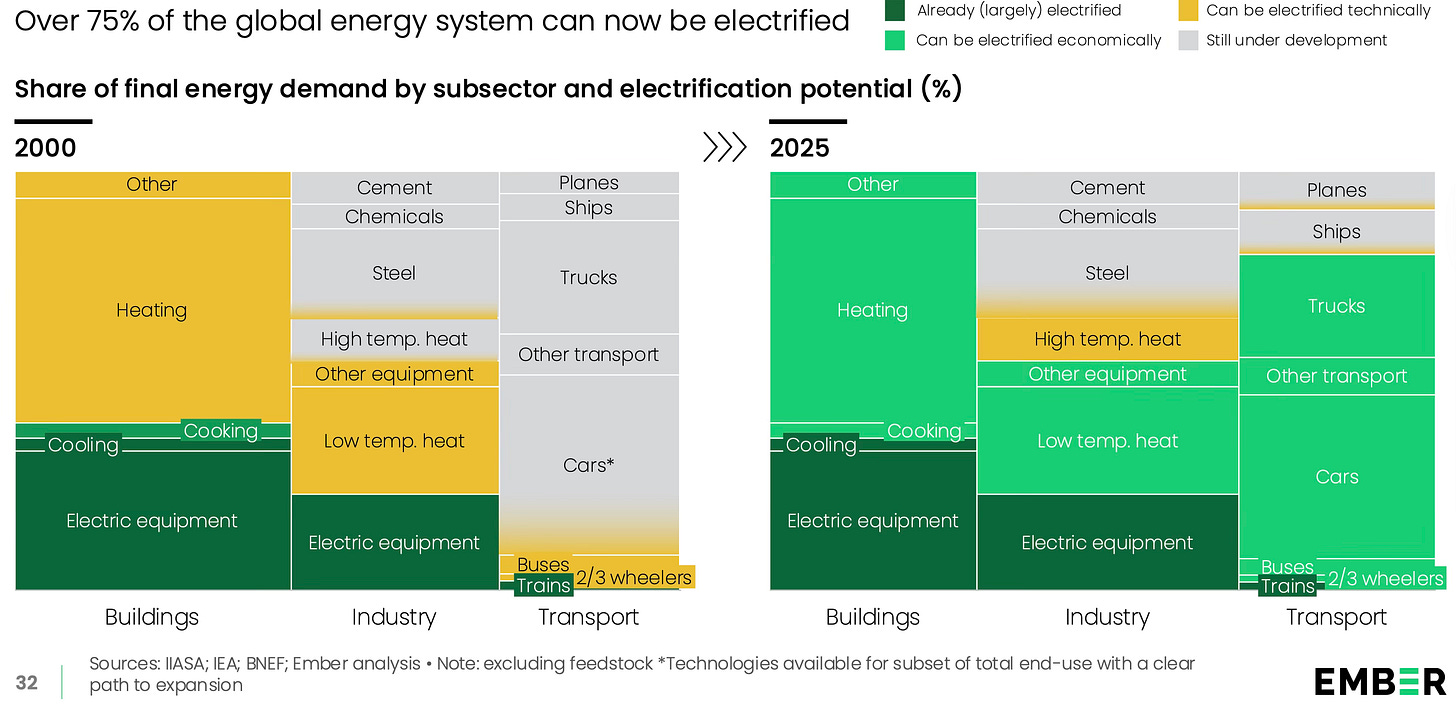

… across sectors…

… and is becoming the major share of incremental demand.

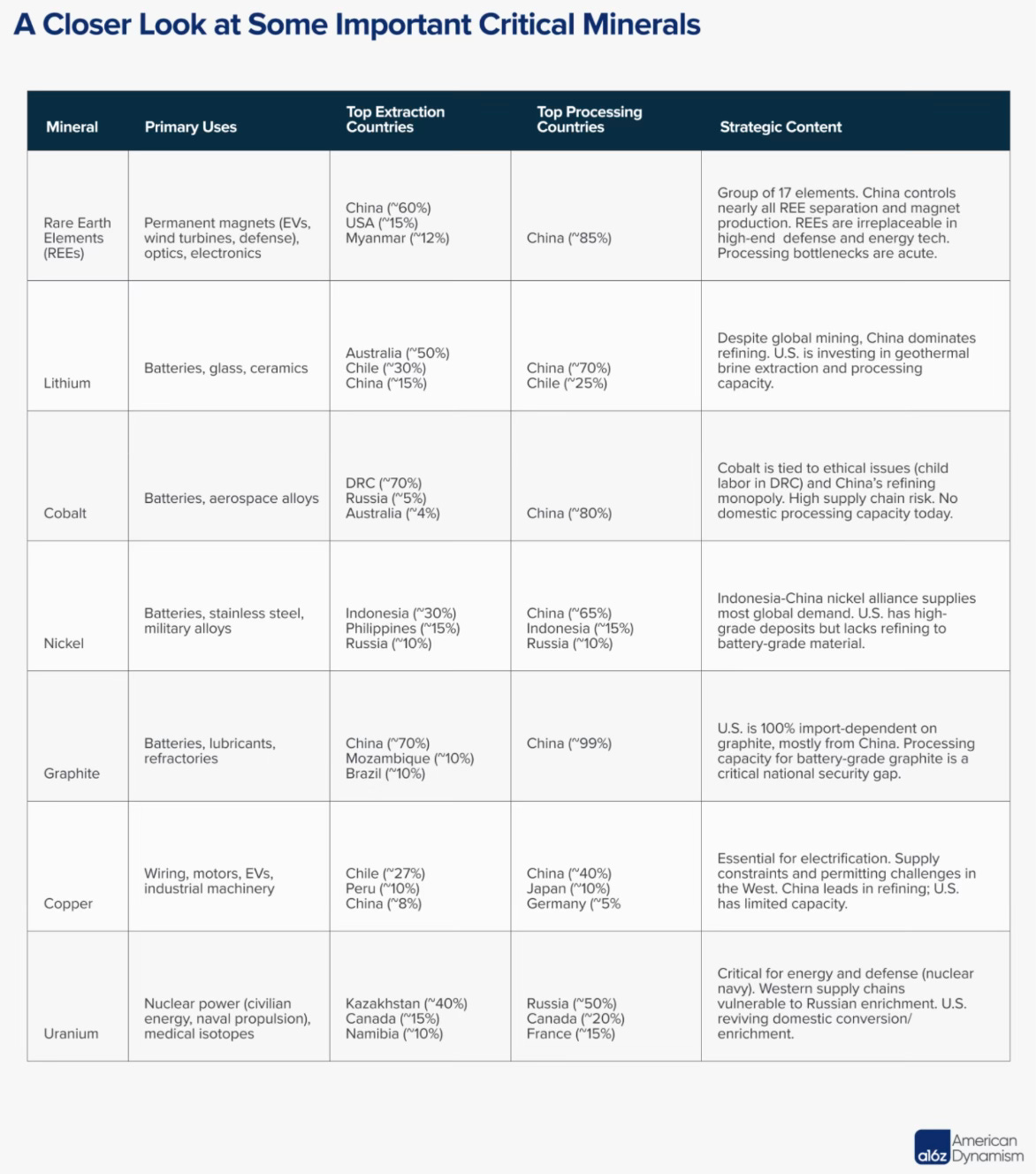

These technologies build on the foundations of an emerging category of critical minerals, which have unique properties, have limited substitutes, and have fragile supply chains, and are “becoming as strategically contested as oil was in the 20th century”. This is a good graphic.

China dominates the midstream of these minerals - the chemistry, metallurgy, and finishing that creates chemicals, alloys, foils, laminations, and powders. It involves the highly specialised and high margin operations of chemical processing (where raw concentrates — from ore, brine, or slurry — are refined into high-purity compounds and metals) and manufacturing of advanced materials with high purity, unique chemical, structural, and magnetic properties (battery precursors and active materials, magnets, and specialty alloys), that feed directly into end-use industries. Manufacturing is more sophisticated and challenging to master.

This isn’t assembly-line work, but precision materials engineering. Processes like heat treatment, doping, sintering, and nanostructuring push performance limits. Minor deviations in particle size or crystal structure can affect battery cycle life or magnet strength. Specs are tight, recipes proprietary, and tolerances unforgiving. Manufacturing follows a different logic than mining or refining: it prioritizes consistency, qualification, and yield over sheer volume. This is especially true for defense-critical components like high-temperature magnets — strategically vital but smaller markets with strict regulatory regimes, long product cycles, and little tolerance for disruption. OEMs tend to value reliability and traceability over novelty. Incumbents like Umicore (cathodes) and Vacuumschmelze (magnets) have spent decades mastering complex processes and earning deep customer trust. Their edge in materials science, process control, and compliance makes it difficult for new entrants to compete.

This is a great summary by McCormick and D’Amico on how the West gifted its leadership in all four parts of the electrotech stack to China.

The four key Electric Stack technologies were invented at various points between the 1960s and 1990s in America, Japan, and the UK, and reached critical maturity around the same time in the 1990s. Then, in many cases, we sold the future. GM sold its neo magnets division, Magnequench, to China for $70 million. A123 Systems, which invented the Lithium Iron Phosphate (LFP) battery, went bankrupt and sold to Wanxiang for $257 million in 2013… By controlling these four technologies, China has become the world leader in everything from EVs to drones to electric bikes to robots.

A giant piece of this is that mastery of this stack applies across domains, allowing market leaders like BYD to make everything from cars, to home energy products, to iPads, to much of the world’s drones. Within the whole sector – the components, software, and expertise largely transfer – meaning mastery of one product of the stack allows success in scaling others. Advantages compound. The result has been China getting the best “LEGO set” in the world, with regards to this stack.

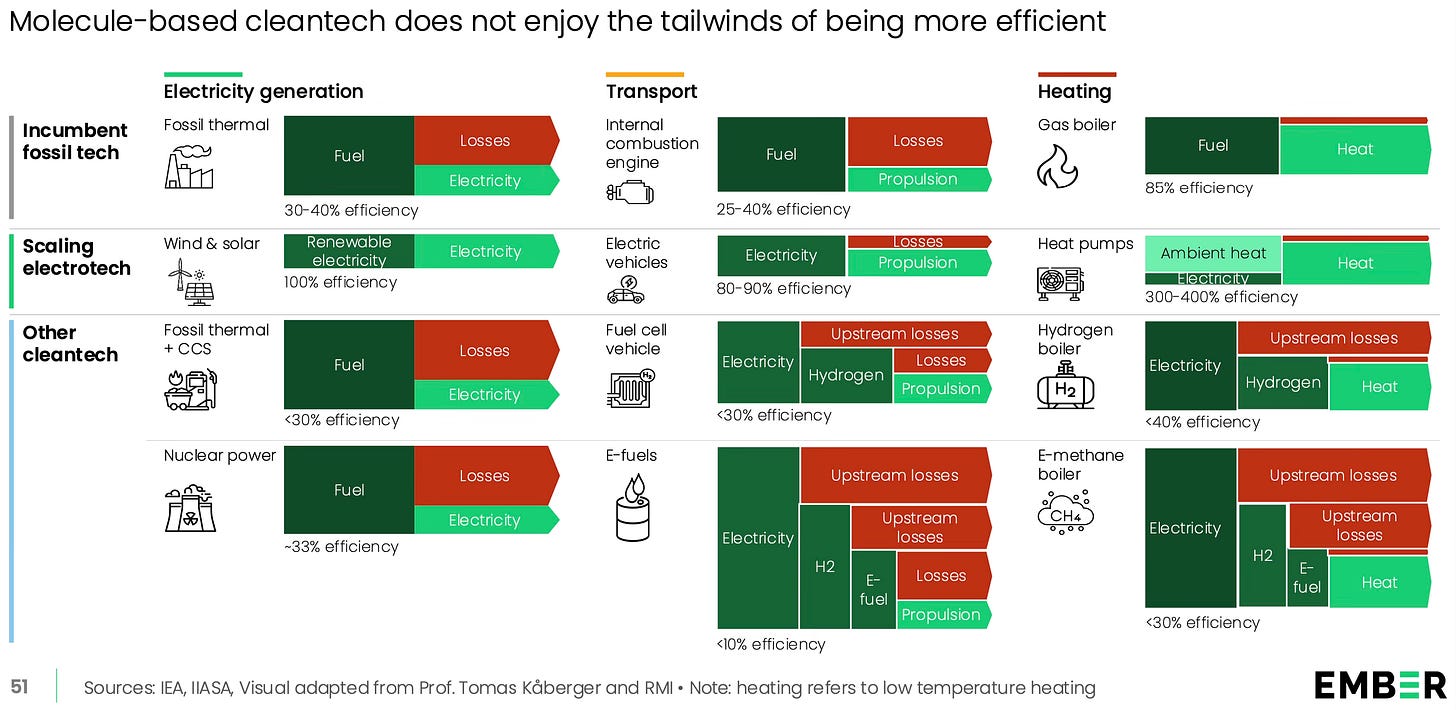

Three imperatives are driving the electrotech revolution - physics, economics, and geopolitics. Let’s briefly examine each. Electrotech is three times more efficient than fossil fuels in sectors making up two-thirds of fossil fuel demand (electricity, road transport, and low-temperature heat), and is more efficient than other solutions like CCS, biomass or hydrogen.

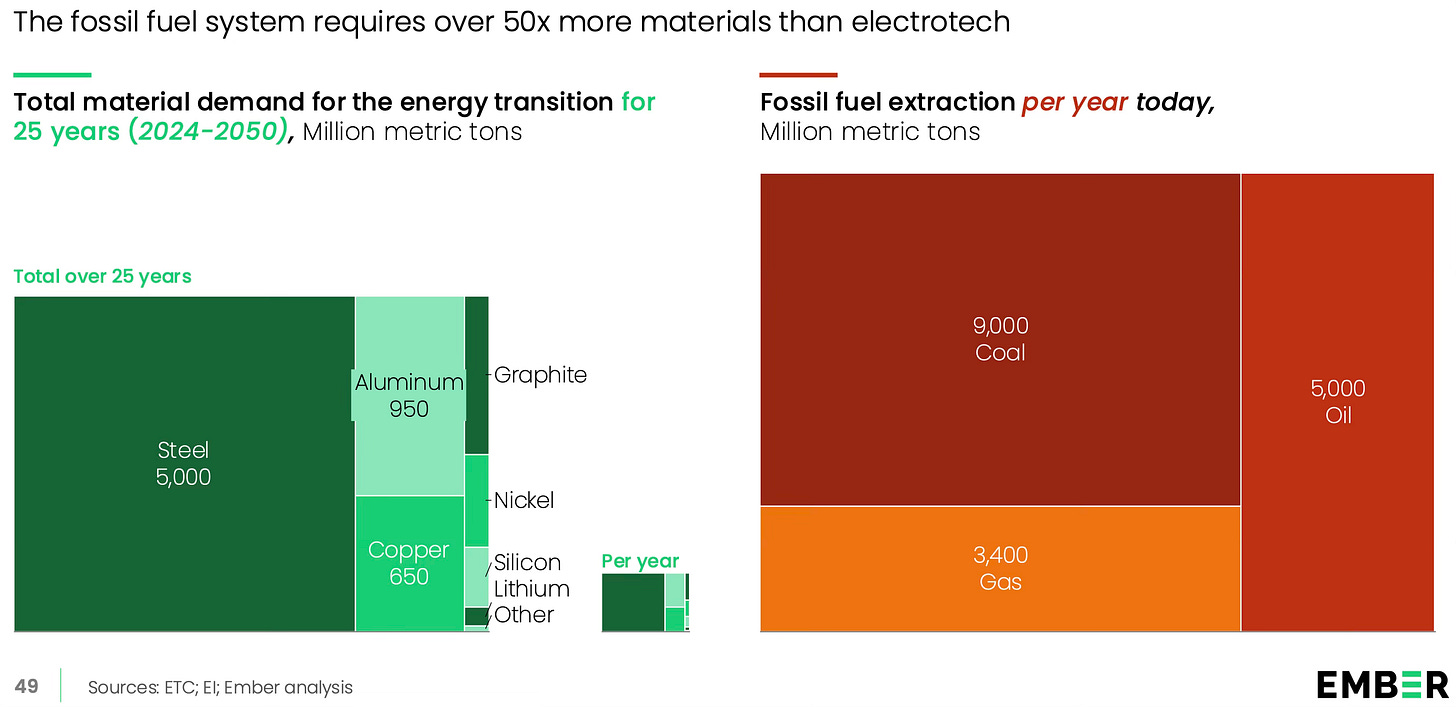

And it requires over 50 times less material than fossil fuel systems.

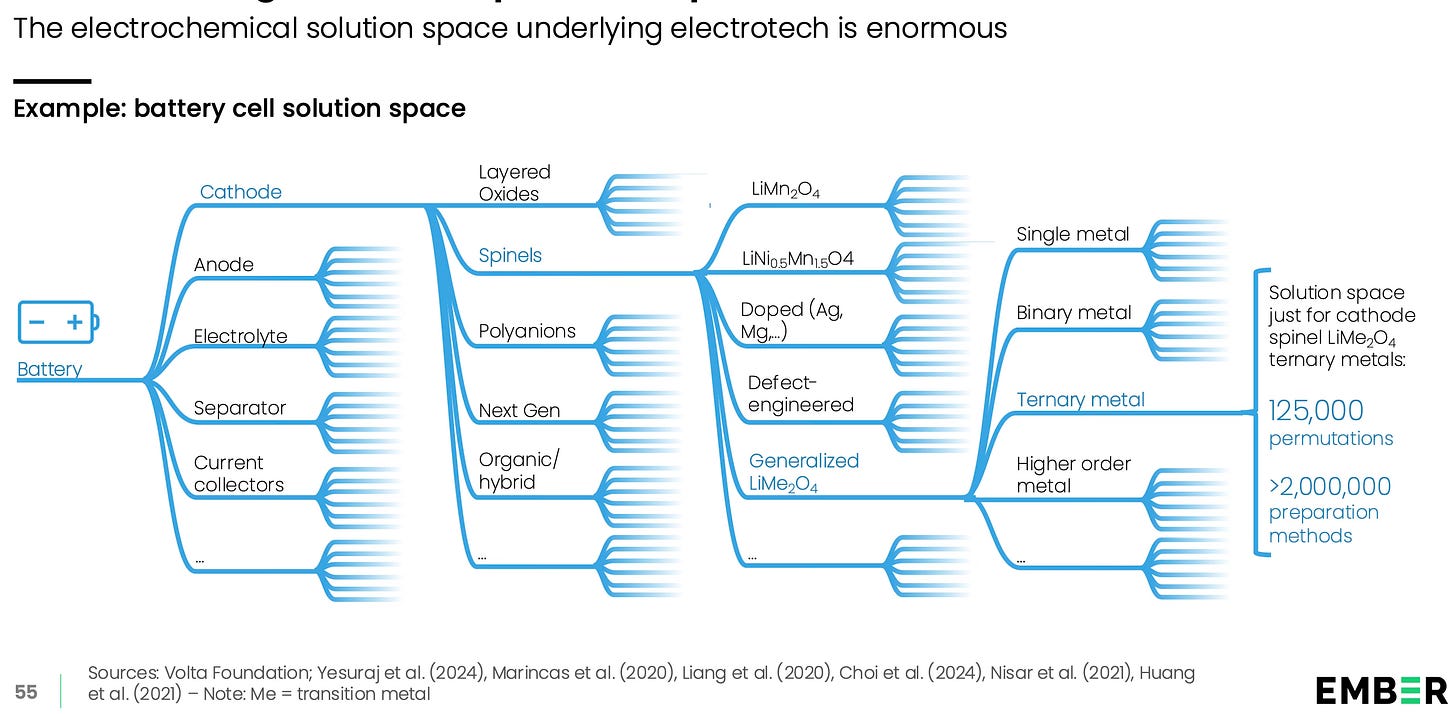

Electrotech has enormous opportunities to innovate and improve efficiencies and drive down costs.

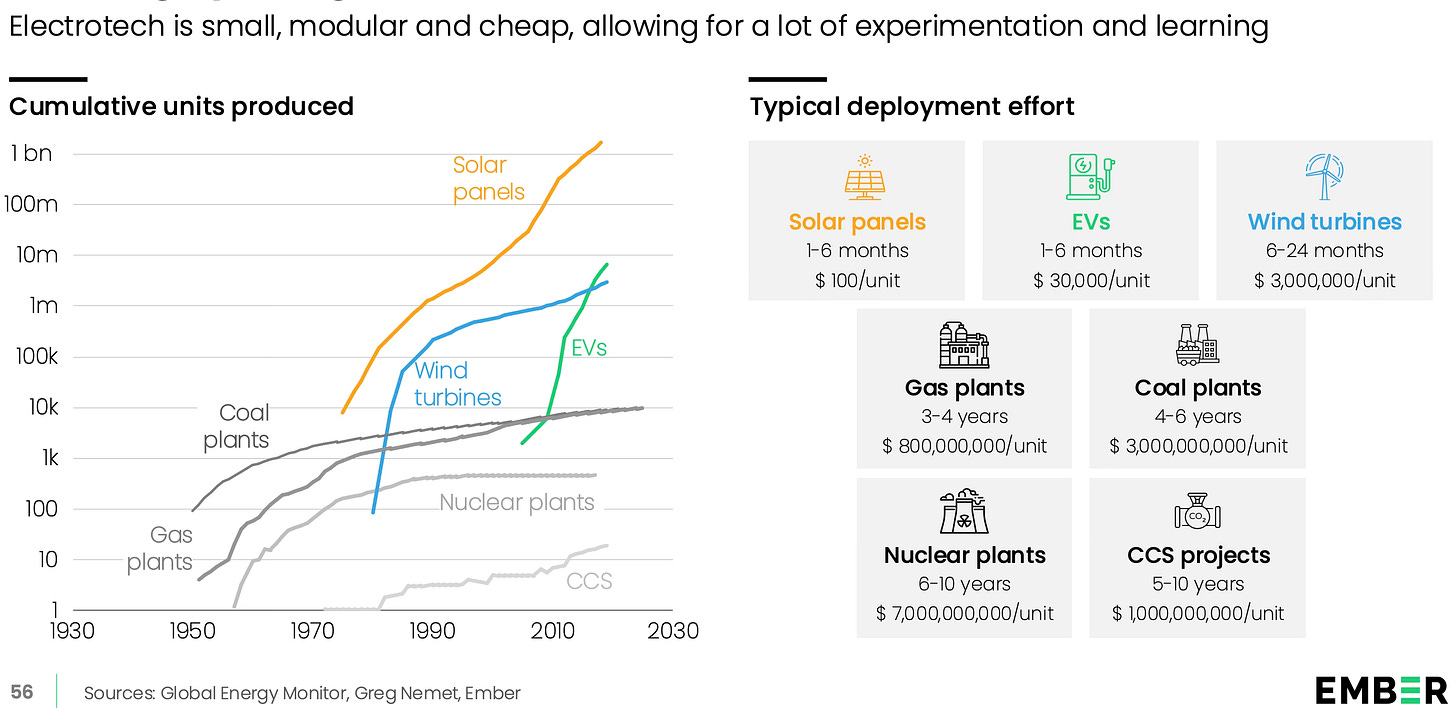

And it is small and modular, thereby allowing for greater scope and span for experimentation.

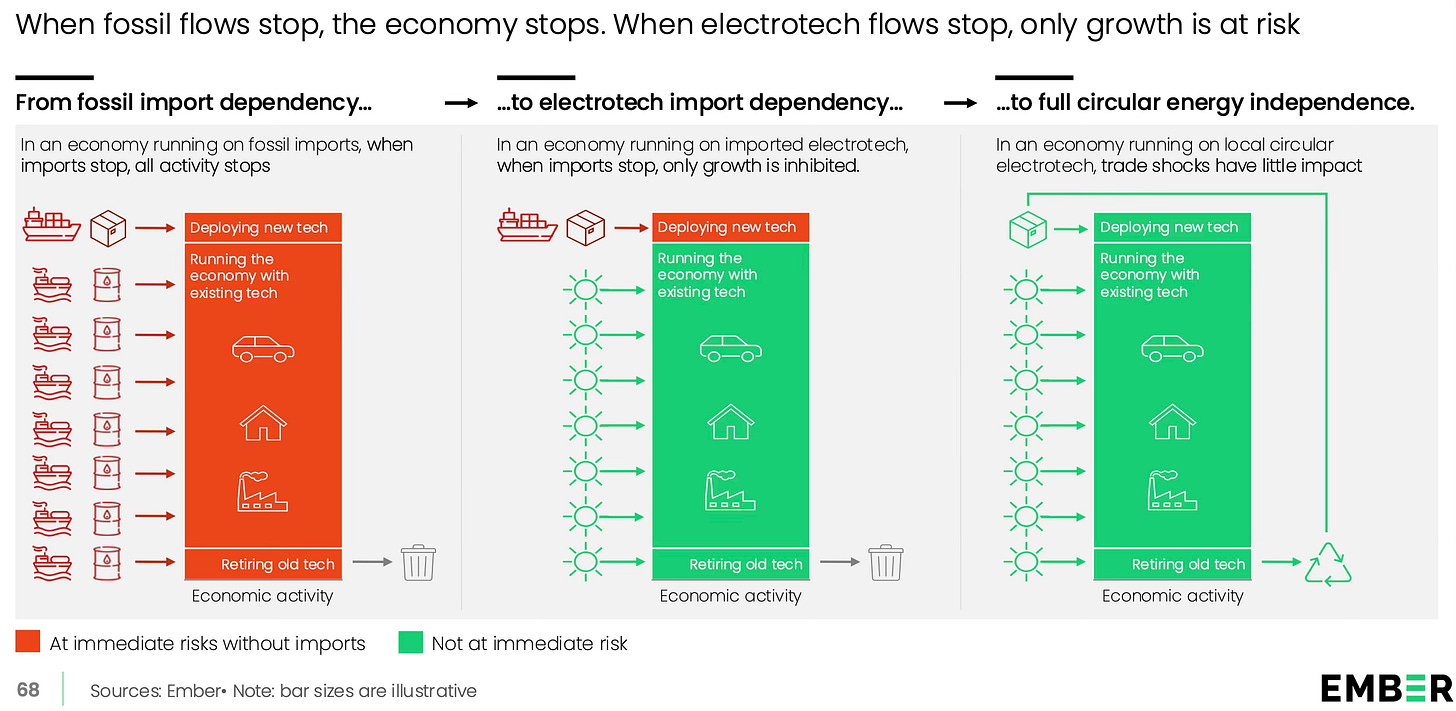

Furthermore, unlike fossil fuels, electrotech fuels (such as solar and wind energy) are available globally, thereby increasing energy security.

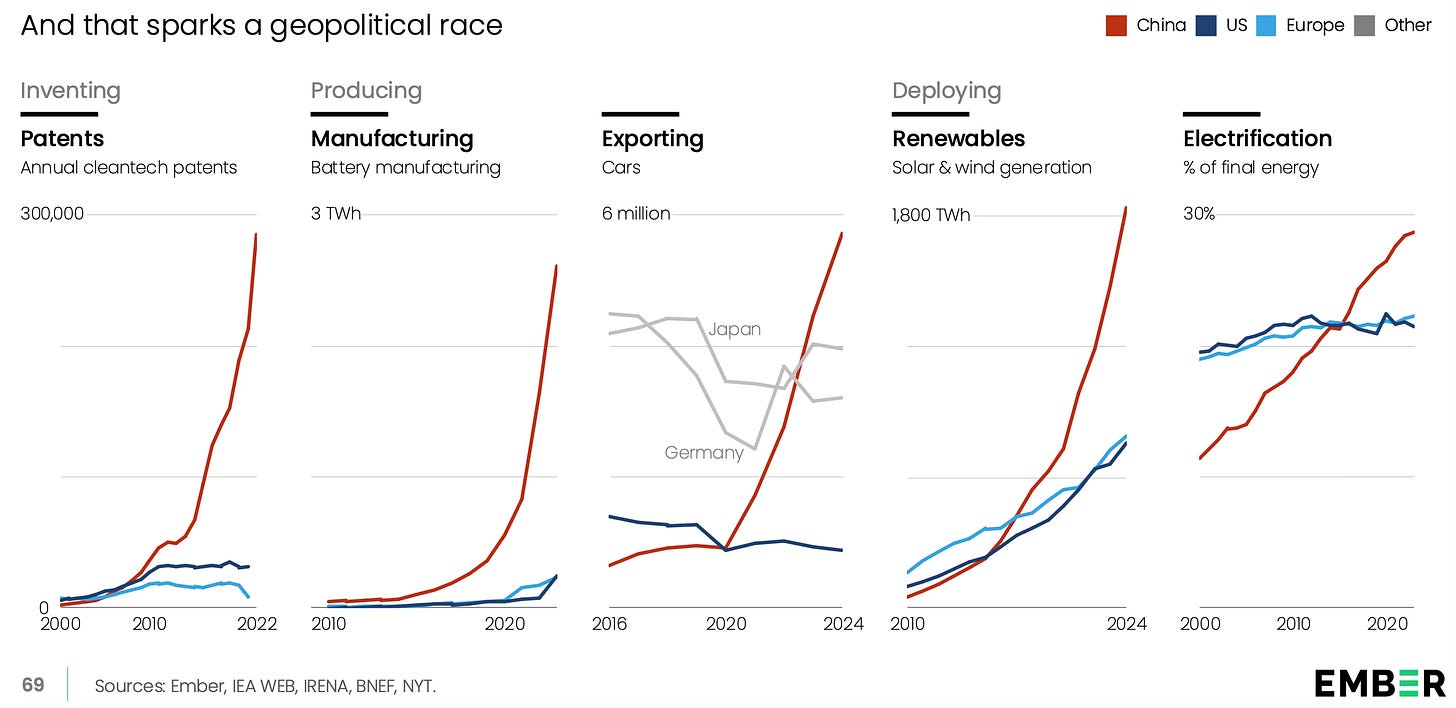

How, China being the runaway leader on electrotech, brings serious security risks.

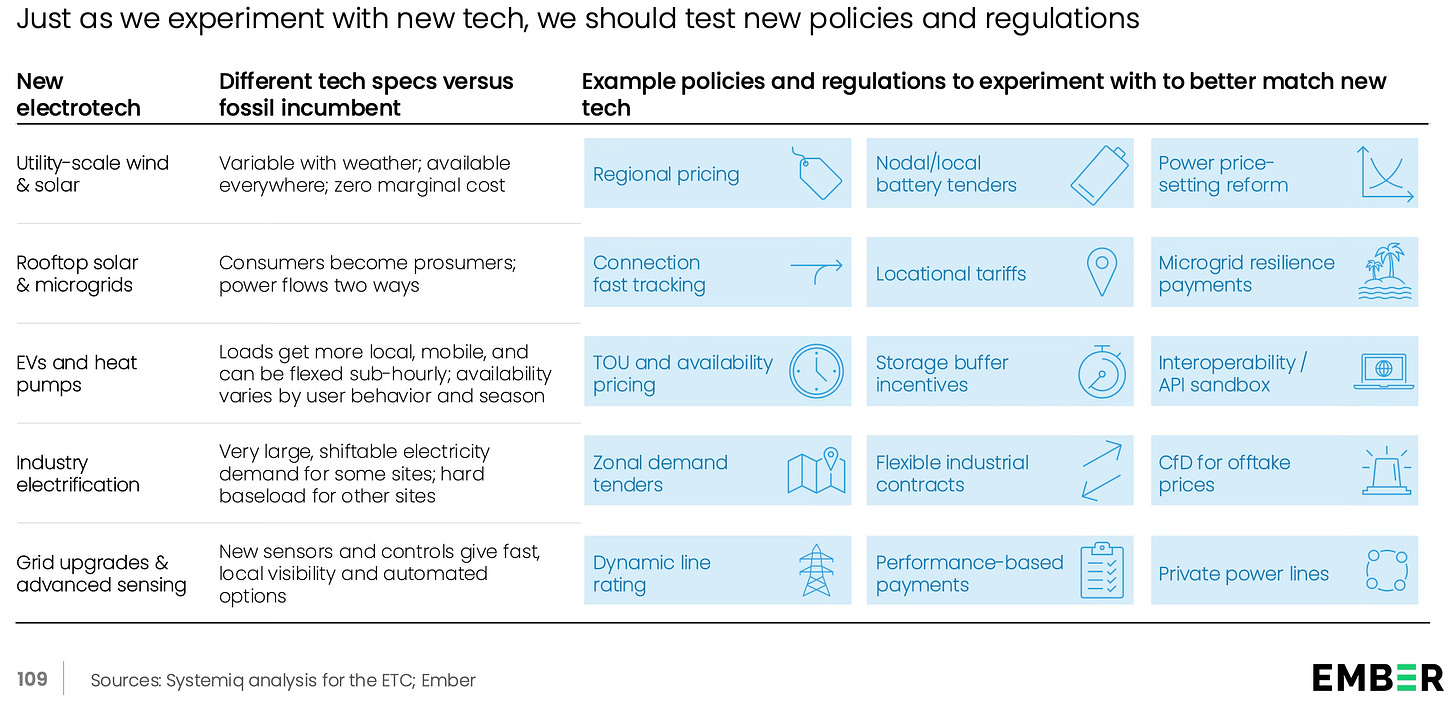

Finally, a matrix of policies aimed at the promotion of electrotech technologies.

No comments:

Post a Comment