This is the latest in the series on the Chinese economy. This post will look at some of the emerging macroeconomic problems and how the country built up its current dominant position in clean energy technologies.

A big problem facing the Chinese economy is the problem of neijuan, or involution (excessive price competition) in a fiercely competitive domestic market. It has made even President Xi Jinping caution against the accumulation of excess capacity.

“Artificial intelligence, computing power and new energy vehicles. Do all provinces in the country have to develop industries in these directions?” Xi told the Central Urban Work Conference, a high-level Communist party meeting on urban development, according to state media.

This has its origins in the shift towards investments in manufacturing, especially into new quality productive forces like green technologies, in the aftermath of the bursting of the real estate bubble in 2021. Despite directives from top, the manufacturing sector shows little signs of slowdown.

But with China’s investment in manufacturing still rising at a blistering pace — up 7.5 per cent this year after a 9.5 per cent rise in 2024 — there is no end in sight. Yan Se, assistant professor in the department of applied economics at the Guanghua School of Management in Peking University, said at a recent seminar that China’s share of global manufacturing value-added could rise to 40 per cent in the next five years, from about 27 per cent now.

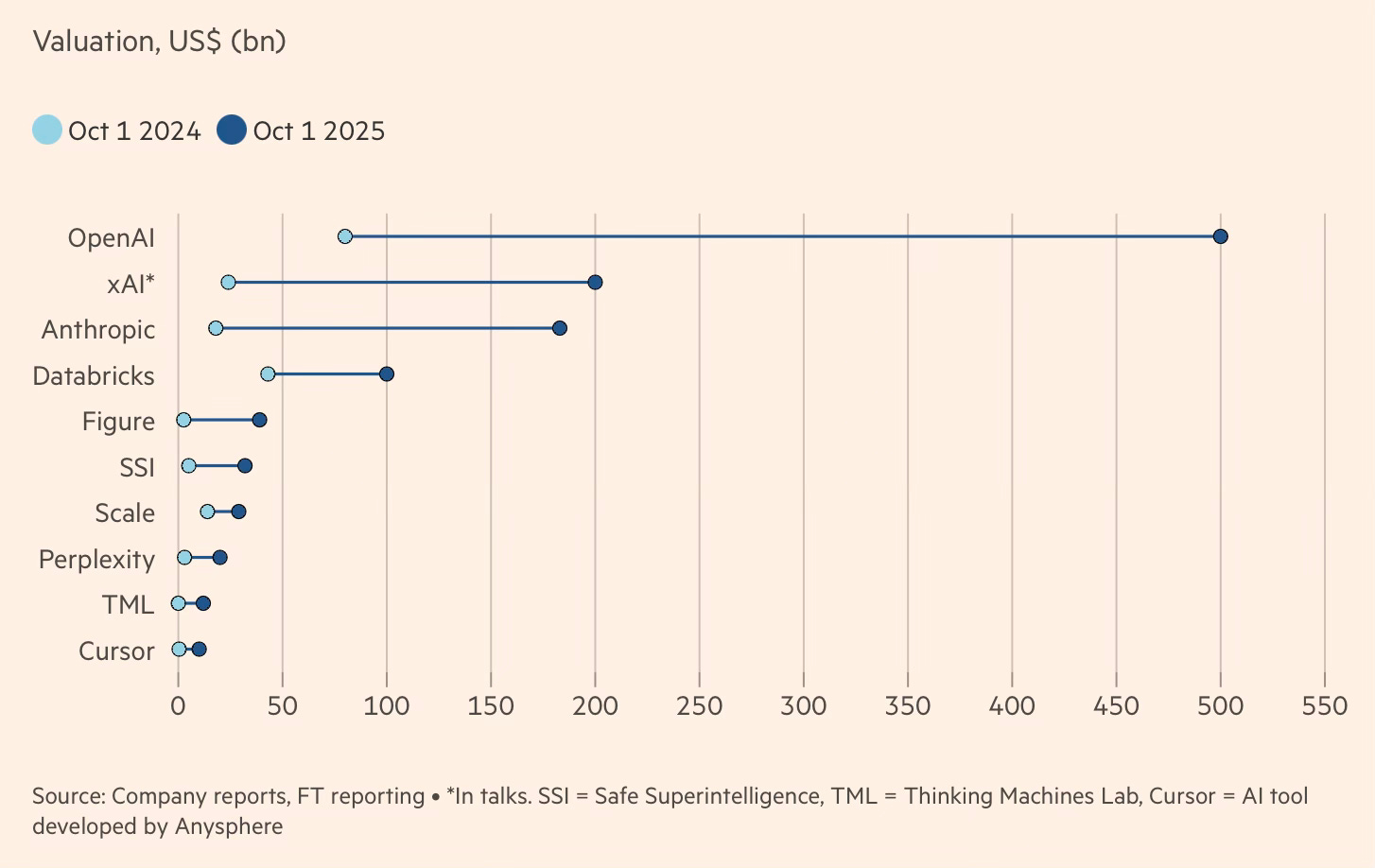

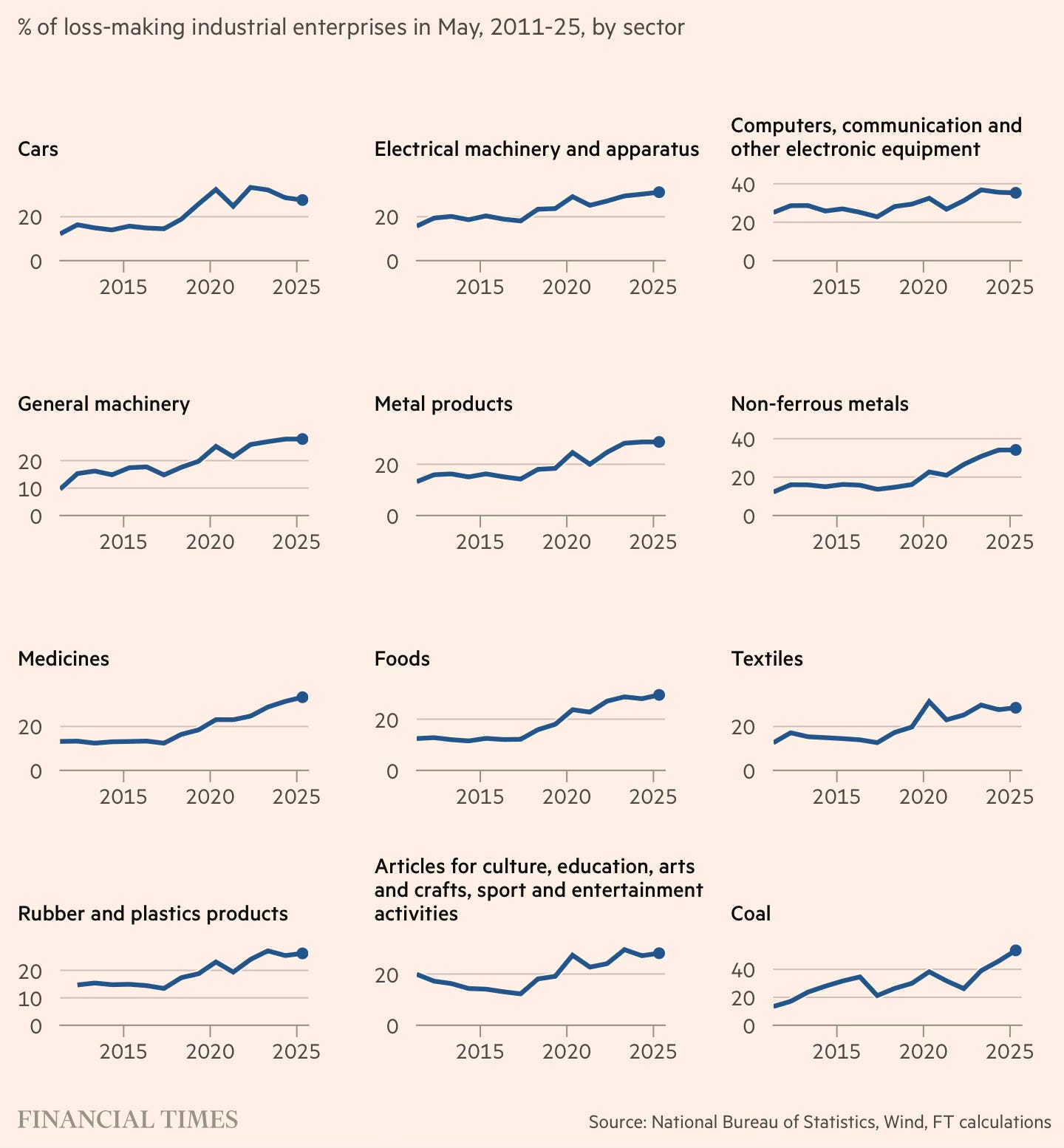

Three graphics that capture the problems posed by China’s manufacturing addiction and the accumulated excess capacity. First, the proportion of loss-making firms has been rising across sectors.

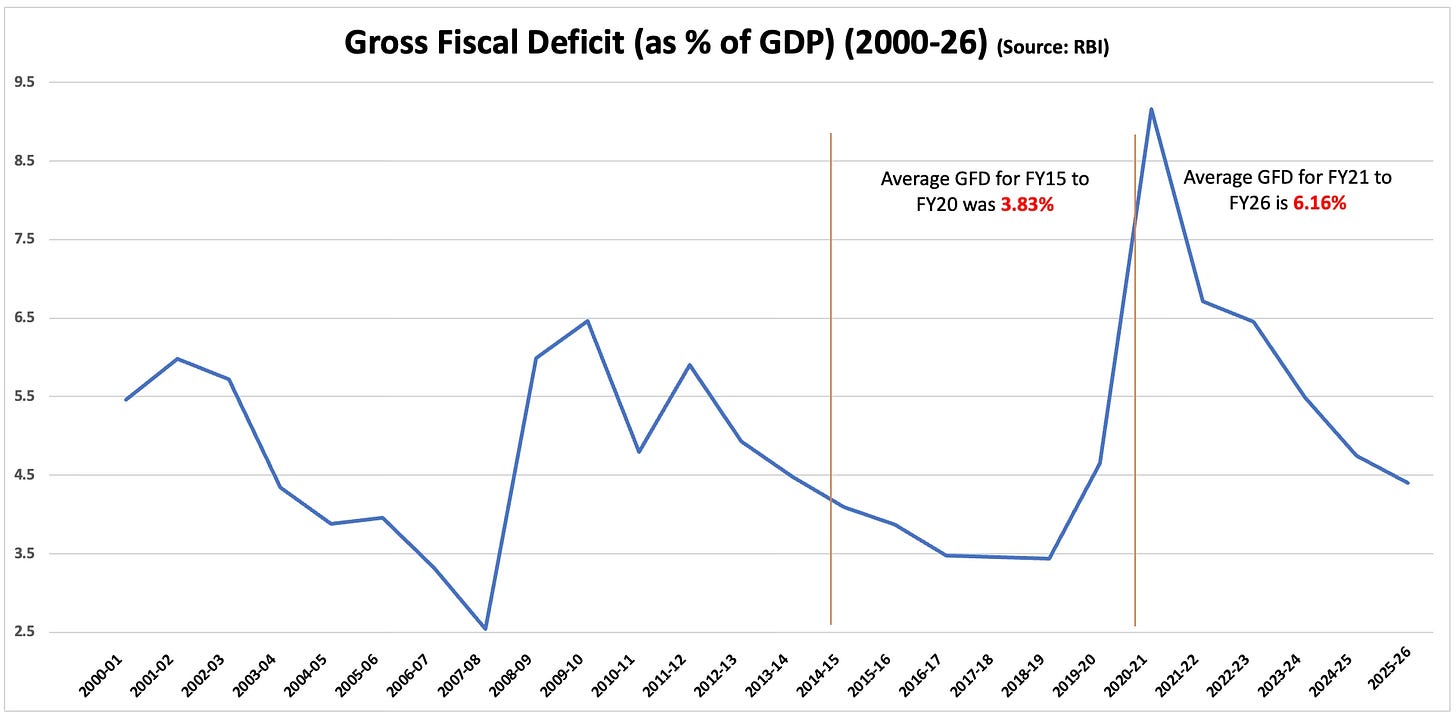

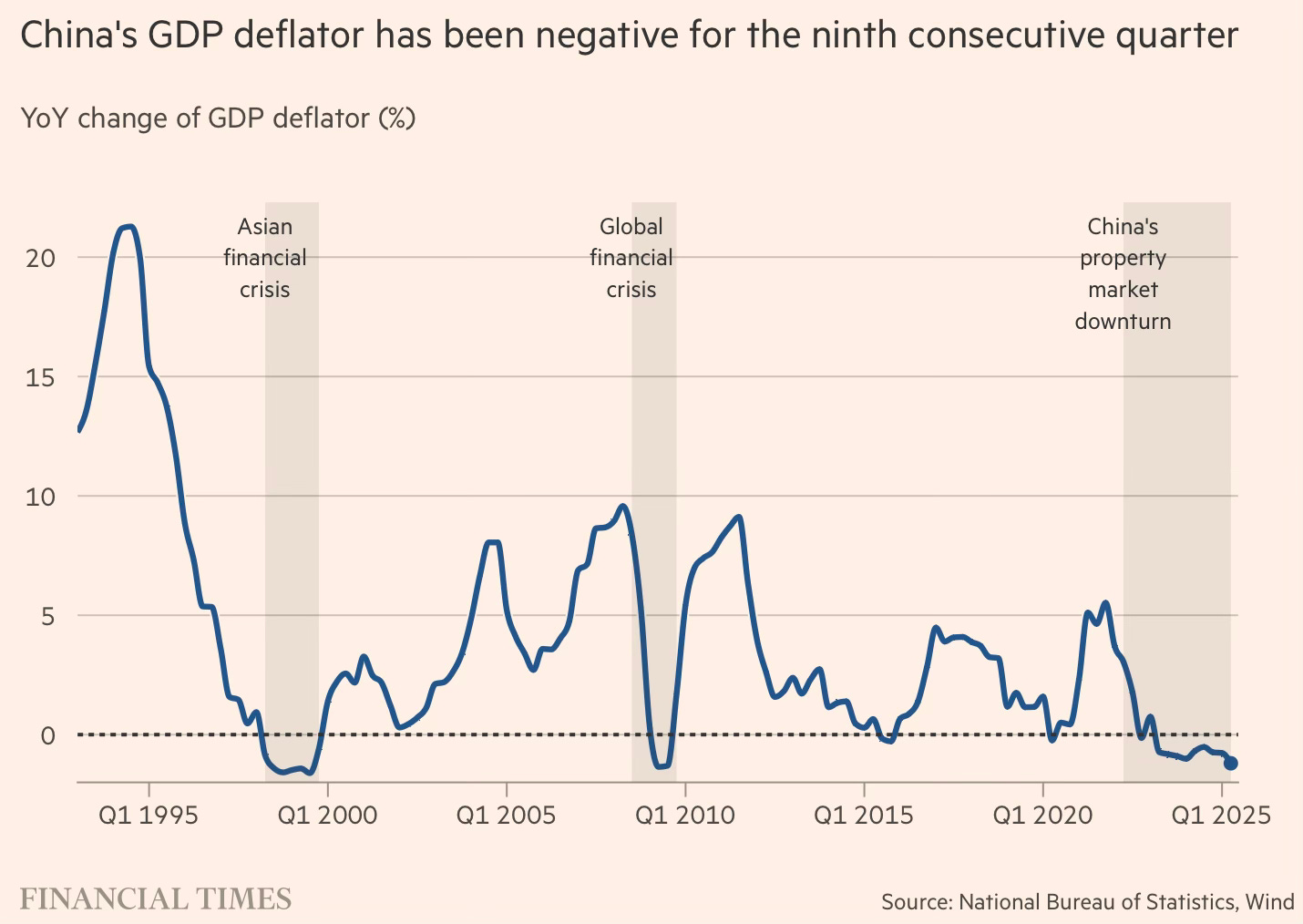

Second, at the macro-level, it is manifesting in the form of nine consective quarters of falling prices.

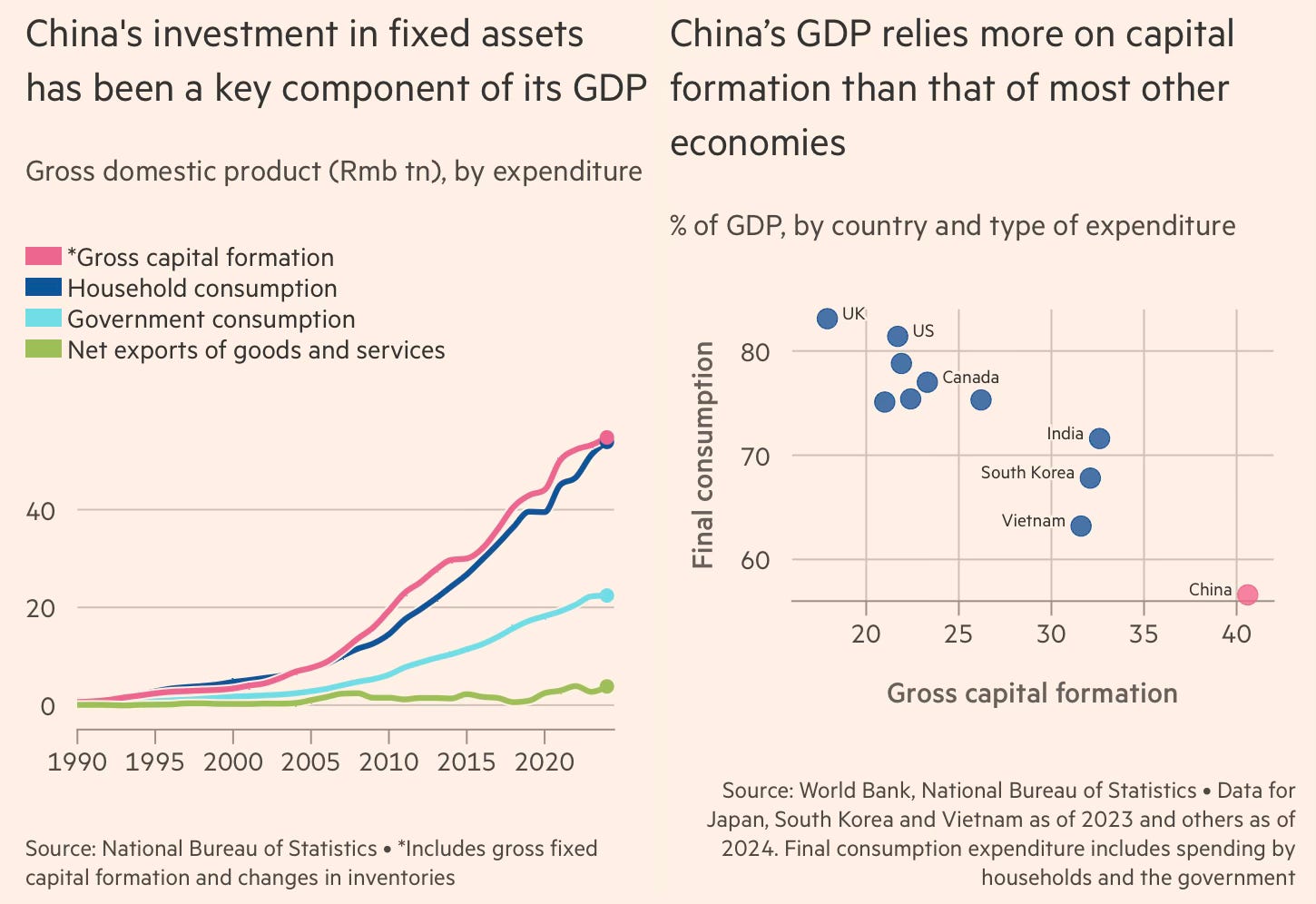

Third, it has deeply distorted the economy’s structure, prioritising capital formation and undermining consumption.

A new report from Yuhan Zhang, principal economist at the China Centre of the Conference Board, says

Many of China’s lower-tier metropolises were heavily dependent on such investment to produce economic growth. Such cities had investment-to-GDP ratios on average of 58 per cent last year, compared with China’s already-high national average of 40 per cent. For OECD member states, the figure is closer to about 22 per cent… The study also found that in lower-tier cities, high investment intensity usually coincided with weak labour productivity and lower total factor productivity — a measure of output per input of capital and labour… “Misallocated investment and duplicated capacity are undermining efficiency,” Zhang wrote in the report, flagging that “long-term gains from ‘new quality productive forces’ require human capital development, innovation, and more market-oriented resource allocation… Heavy fixed-asset spending appears to reduce efficiency rather than boost it, even if local governments are pouring money into ‘new quality productive forces’,” Zhang concluded.

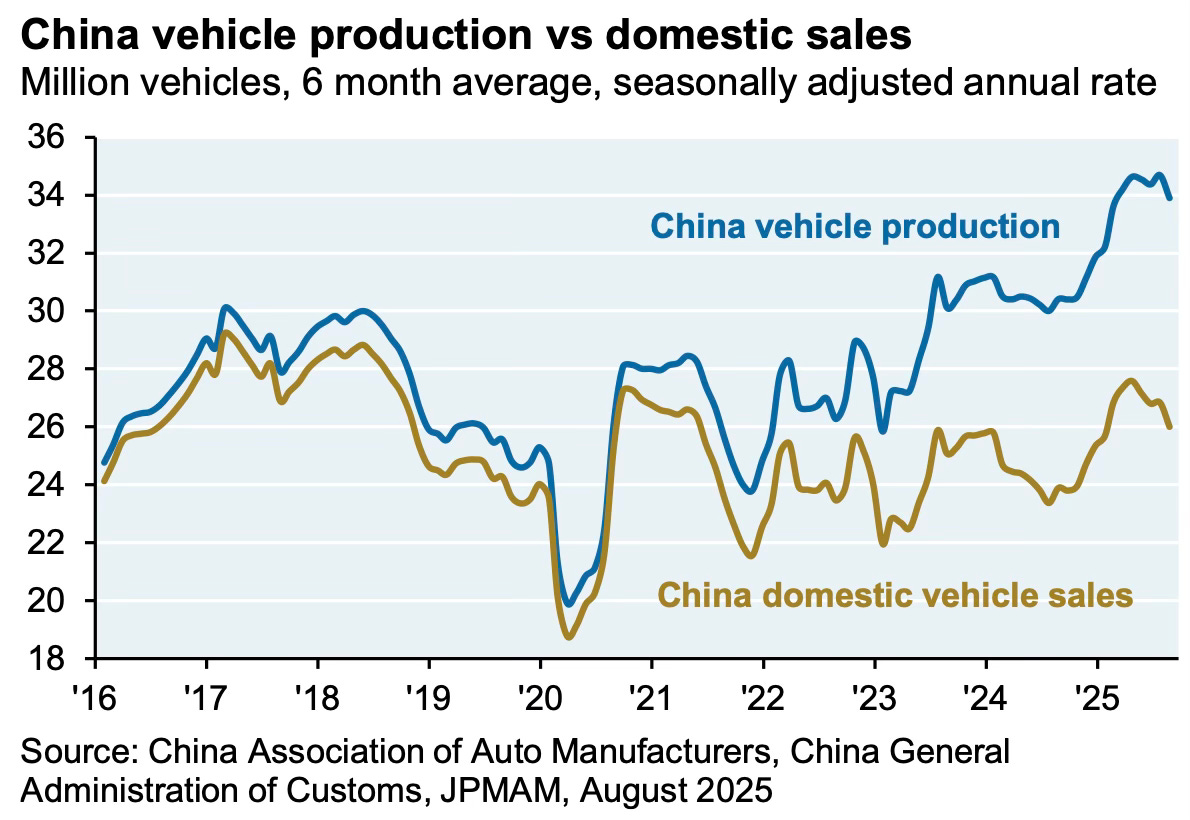

A few graphics from JP Morgan that reiterate these trends. Nowhere is excess capacity more pronounced than in the automotive industry.

Even as China’s exports have surged, the intense competition has been strangling the companies involved.

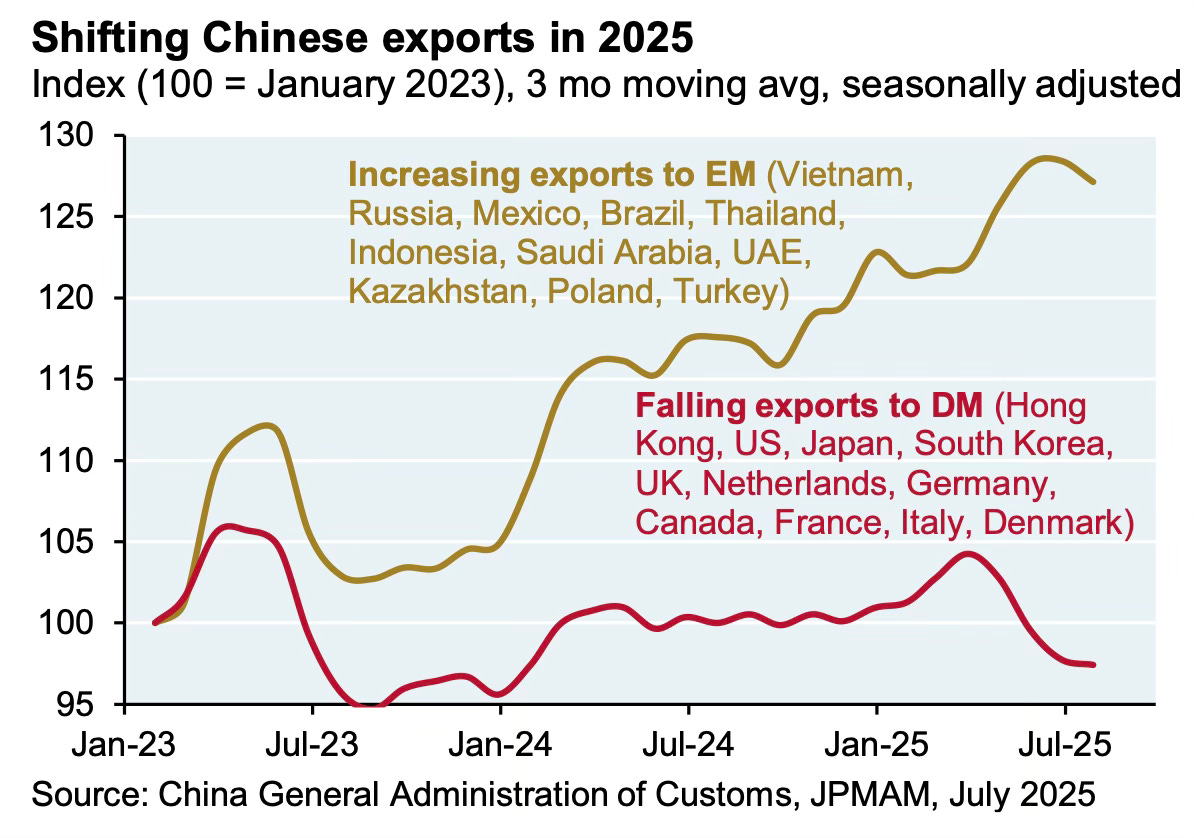

2. As trade tensions rise and the Cold War intensifies, Chinese exports to Western markets have been declining, and have been offset by a steep rise in exports to the emerging markets.

The JP Morgan report says that Mexico, Turkey, Indonesia, Brazil, South Africa, Thailand and Vietnam are among the countries that have imposed tariffs on Chinese industrial or consumer exports.

Chinese exports to other developing countries will become an ever-growing concern in its relationship with these countries. Thanks to the Cold War, China’s excess capacity is now being exported to developing country peers.

All this makes it critically important that China finds a way to rein in its excess capacity. However, given the scale of excess capacity across sectors, this may not be possible without inflicting significant domestic pain in terms of job losses and knock-on effects on the economy. The other alternative is to incentivise domestic consumption, something which Beijing has so far been very reluctant to pursue.

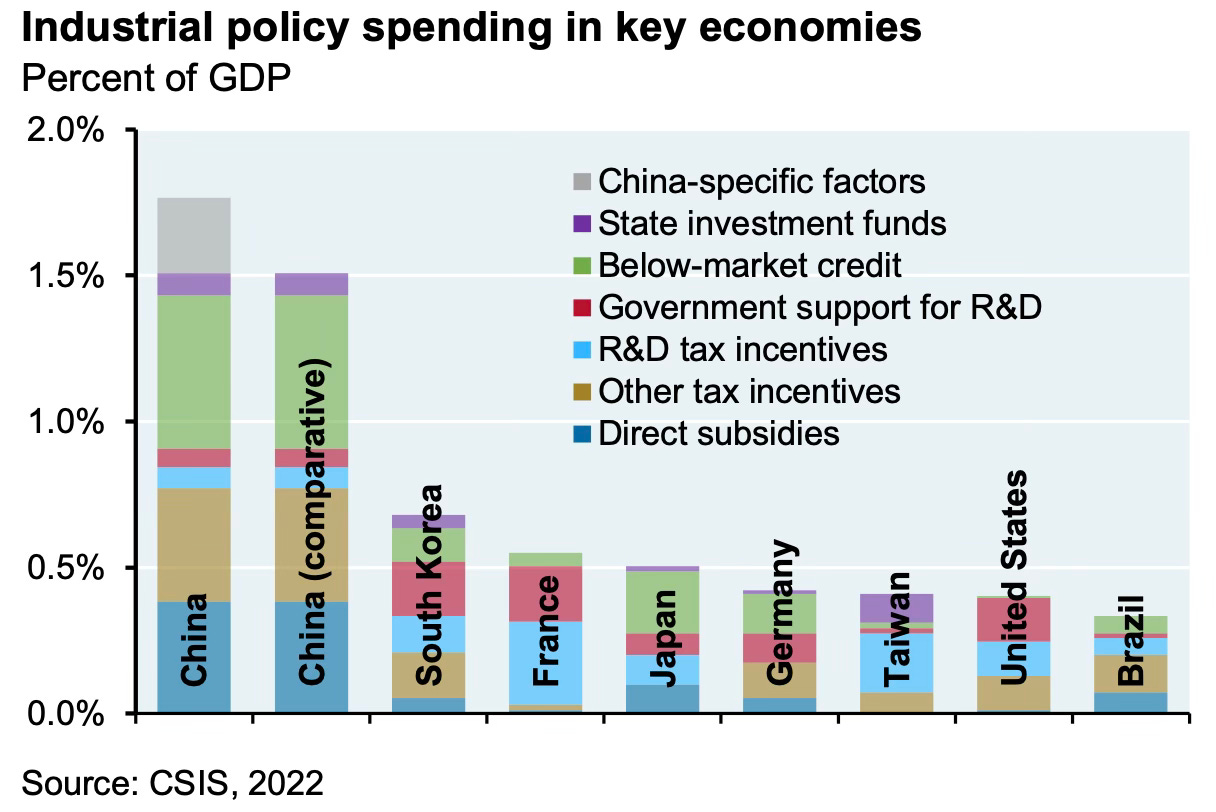

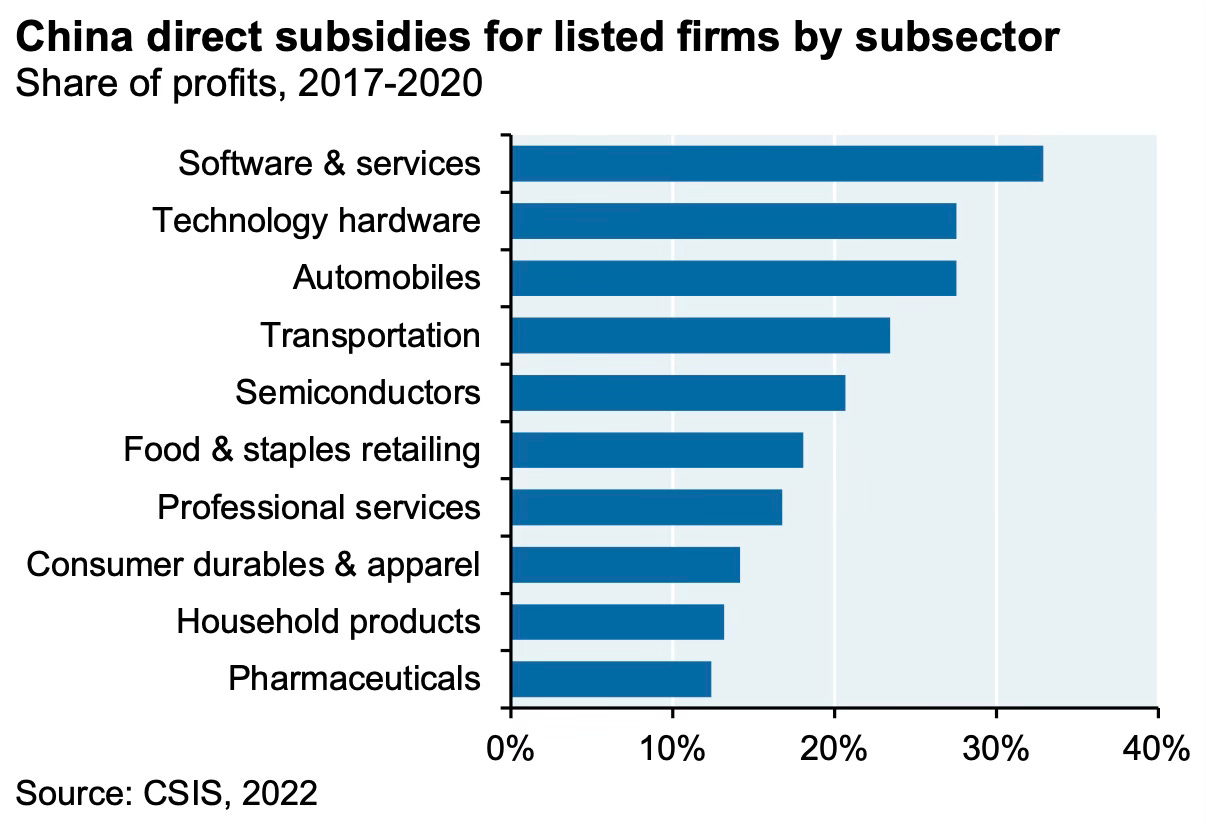

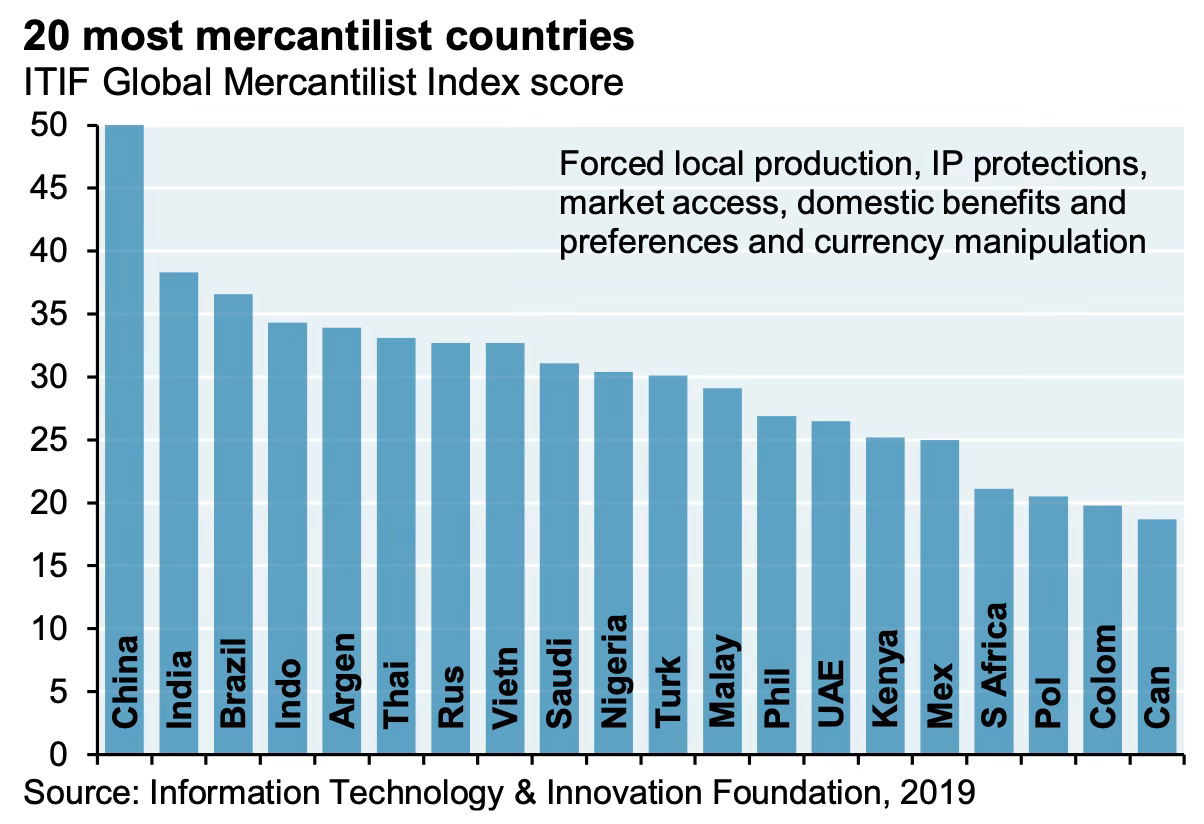

3. The JP Morgan report has some very relevant graphics on how mercantilist the Chinese economy is. The extent of industrial policy support far exceeds other major economies.

In many sectors, direct subsidies alone make up 15-35% of firm profits.

All this makes China the standout mercantilist economy.

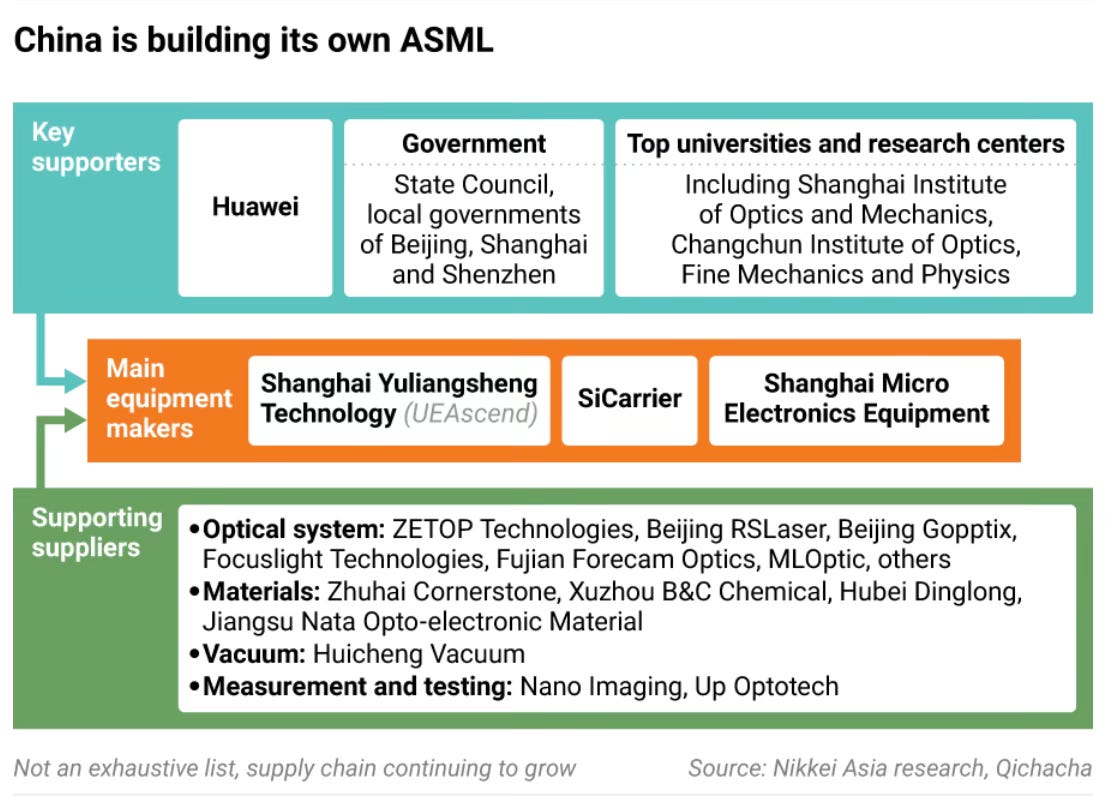

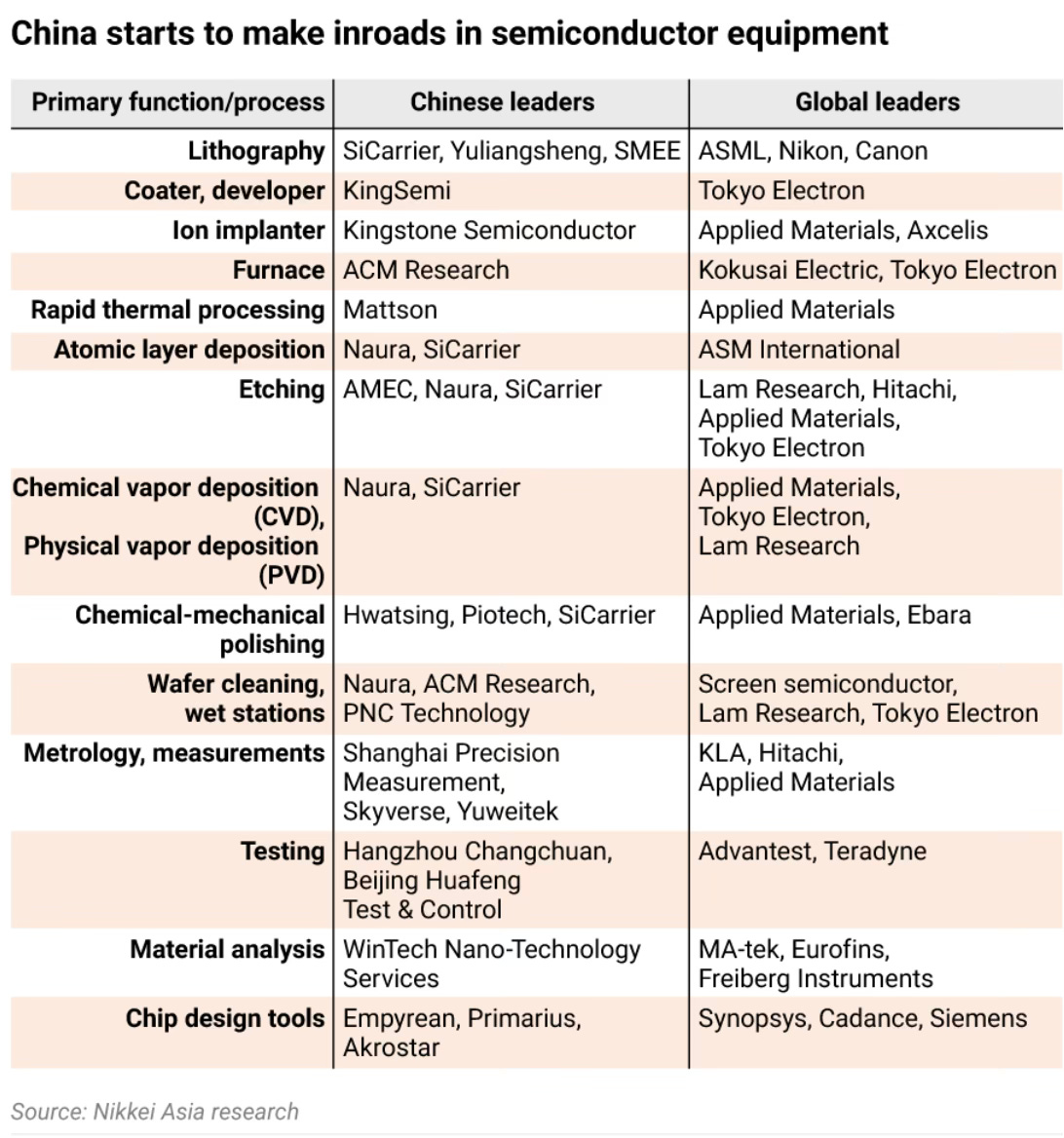

4. One of the sectors where China still lags considerably behind the West, despite pouring tens of billions of dollars, is semiconductor chip manufacturing. However, it’s now making serious efforts to address the deficiencies and catch up. One area of focus is on the manufacture of equipment used to fabricate chips.

Nikkei Asian Review has an excellent article on China’s attempts to master lithography techniques to make its version of ASML’s DUV machines. Chinese chip manufacturers like SMIC have succeeded in making tools used for etching, measurements, deposition, chemical polishing and more, but struggled with making the lithography machine.

The process of projecting and printing chip developers' designs onto a wafer is vital to the ultimate performance of the chip. But lithography machines are so complex and expensive that only three companies in the world -- ASML of the Netherlands and Japan's Canon and Nikon -- are capable of producing them. Last year, lithography accounted for nearly 25% of global spending on chipmaking equipment, according to industry group SEMI… ASML is the largest global chip tool maker by market capitalization, as well as the leader in immersion deep ultraviolet (DUV) technology, used to make chips for everything from smartphones to cars to defense equipment. The Dutch company is also the exclusive maker of extreme ultraviolet (EUV) lithography tools, which chip titans like TSMC, Samsung and Intel use to make the world's most advanced processors and memory chips… The high-NA EUV machine, as it is called, is now being shipped to TSMC and Intel for field trials, and the company expects broader industry adoption to follow. At $350 million apiece, the machine is the most expensive chipmaking tool ever built… ASML's high-NA EUV lithography machine weighs 150,000 kg, stretches 14 meters long by 4 meters high and 4 meters wide, and is made up of millions of components. Industry sources call it the most complex machine ever built.

This is a good illustration of how complex these machines are and the difficulties in mastering their manufacture.

EUV machines had to be completely redesigned, as its light source has a wavelength of just 13.5 nanometers, compared to 193-nanometers used in earlier DUV systems. In general, the shorter the light wavelength, the finer the chip design circuit patterns that can be printed. It took more than 20 years to turn the EUV concept into a commercial reality. While the first sample machines were shipped to clients in 2006, it wasn't until 2019 that TSMC and Samsung were using them to produce the world's most advanced chips. Developing high-NA EUV, the next generation of the technology, was just as complex. It took more than eight years, for example, just to redesign the projection optics and illumination systems, the core part of the machine that shapes and focuses the light to project chip designs onto wafers. The NA in the machine's name stands for numerical aperture, a measure of the ability of an optical system to collect and focus light. NA is a key factor in determining how finely circuits can be printed onto wafers. In simple terms, a higher NA means a machine can print smaller chip features. ASML supplier Carl Zeiss says the optical system in a high-NA EUV machine contains around 65,000 parts and takes a year to produce. Developing the system took over 10 million working hours and 25 years of collaboration with ASML..

Chiang Shang-yi, a board director of Foxconn and former R&D chief of TSMC, described lithography as “the most complex and resource-intensive step in chipmaking” and lithography machines as harder to build than other chip equipment. “ASML’s exclusivity, particularly in EUV tools, is greater than that of TSMC, the world’s top chipmaker, in making cutting-edge chips. Its success comes not only from developing its own technology but also from exclusive partnerships with top suppliers like Zeiss and Cymer.” ASML acquired Cymer in 2013 and took a nearly 25% stake in Carl Zeiss SMT, a subsidiary of Zeiss making advanced optics, in 2016… Mitsunobu Koshiba, former chairman of Japanese photoresist maker JSR, described ASML's machines as the "most complicated tool on this planet" and not something that every country can hope to produce.

Given the massive amount of knowledge and partners that must be brought together to make a lithography machine, it’s perhaps the most difficult equipment to manufacture. But that has not prevented the likes of SMIC and Huawei from trying.

In fact, Chinese firms have been making inroads across the semiconductor equipment landscape.

China's top five chip tool makers have flourished amid the escalation of U.S.-China tensions since 2019. Their combined revenue has grown by 473% since 2019, with four out of five reporting record profits in 2024, Nikkei Asia's analysis found. In every chipmaking step except lithography, China now has its own player that could potentially challenge global leaders. Naura, often referred to as China's version of Applied Materials, is now the world's sixth-largest chip tool maker by revenue.

This is an illustration of how the Chinese have been strategic in their engagements, compared to short-sighted US manufacturers who are now scrambling, for example, in procuring rare earth metals.

Chinese chipmakers are also continuing to stockpile equipment from global leaders when possible, purchasing nearly $34 billion worth of such tools from Japan between 2020 and 2024, according to Nikkei Asia analysis of Chinese customs data… In lithography, China's short-term strategy remains stockpiling. To hedge against further export controls, China purchased 8.92 billion euros ($10.45 billion) worth of tools from ASML in 2024. That rush of orders led to China accounting for 41% of ASML's system sales that year, the highest share of any market.

5. Arguably the most impressive industrial success story to emerge from China is its spectacular dominance of clean energy generation technologies. Reflecting this success, and even as clean energy pursuit slows down elsewhere, at the recent UNGA session, President Xi Jinping said that China would reduce its economy-wide greenhouse gas emissions and expand renewable energy six-fold in coming years.

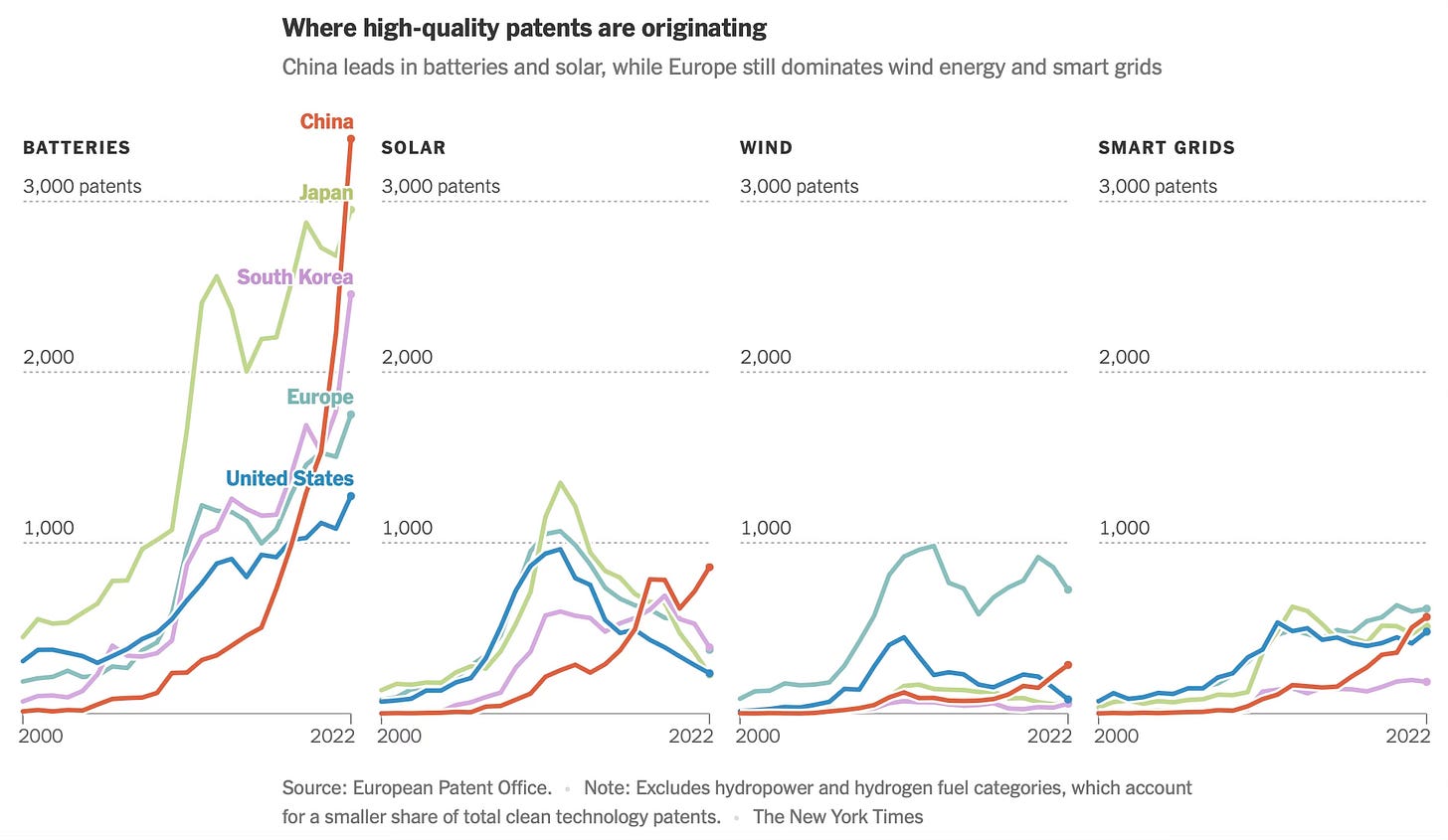

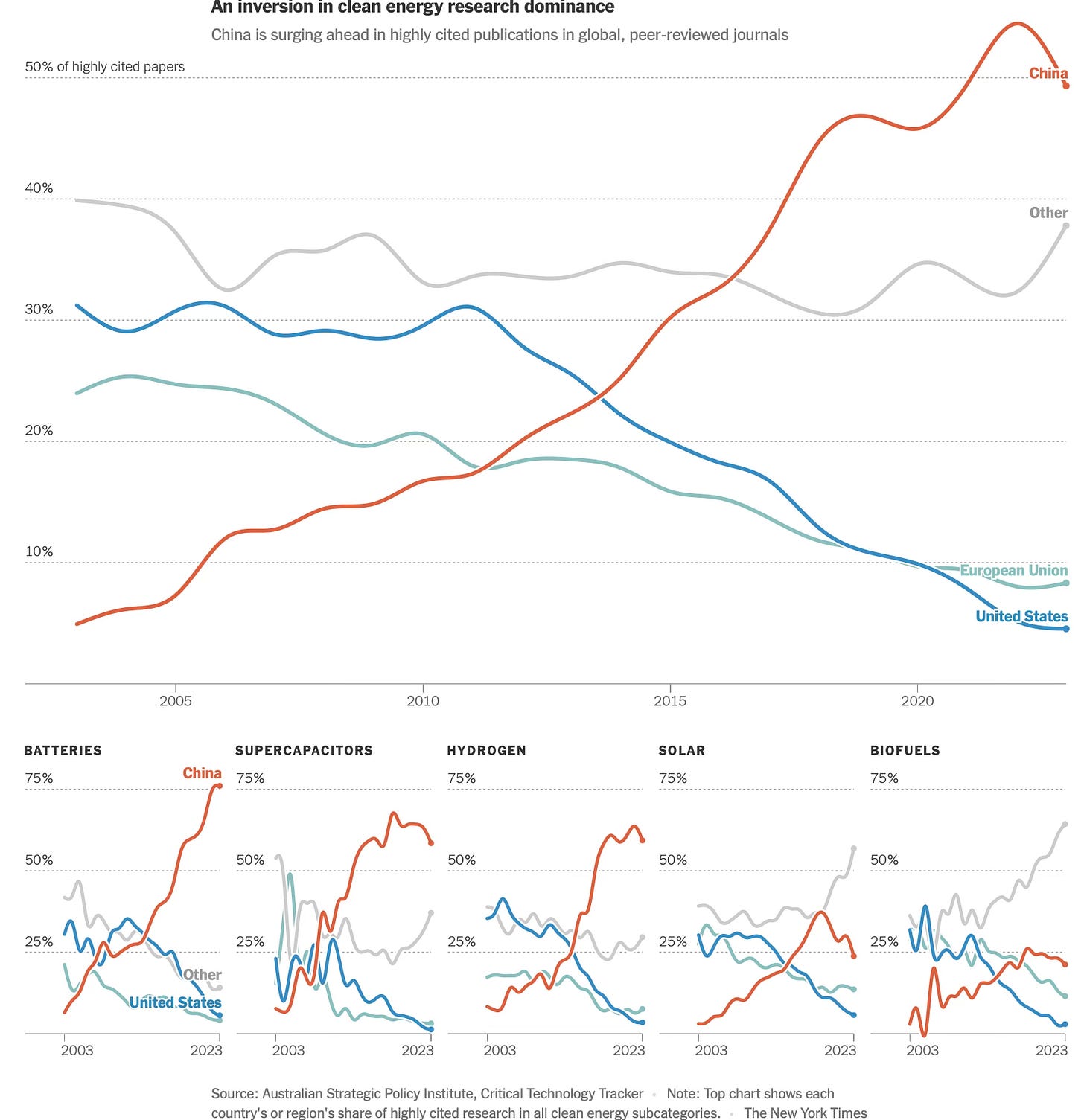

From being a copycat in clean technologies, over the last two decades China has emerged as the undisputed global leader in industrial scale innovation and R&D in the whole array of clean energy sectors.

See also this.

In 2015, the Chinese government initiated the Made in China 2025 program, to provide companies in 10 strategic industries with large, low-interest loans from state owned financiers, assistance in acquiring foreign competitors, and generous subsidies for scientific research. The objective was to control 80% of the domestic markets in those industries by 2025. Far surpassing those targets, the Chinese clean technology companies have come to dominate domestic and global markets.

While Western countries like the United States and Australia pioneered now-widespread technologies like solar panels, batteries and supercapacitors (which are like batteries, only smaller, and provide quick bursts of energy), China is now building on those designs and creating new, groundbreaking versions… The Chinese government has encouraged cutthroat domestic competition that some economists have likened to “economic Darwinism.” Sam Adham, head of battery materials at CRU Group, a market analysis company, described a typical scenario: First comes a flood of subsidies into a particular industry that the government has deemed strategic. Companies pile in, filing dozens or even hundreds of patents along the way. In the final stage, Mr. Adham said, the government pulls the subsidies and the less competitive companies essentially are “culled,” while “the remaining companies emerge stronger and they go overseas and take market share there.”…

Take, for instance, batteries for electric vehicles. While the original breakthroughs in producing lithium-ion batteries were made in the United States three decades ago, further research received little government backing there. Meanwhile, Chinese companies grabbed the baton. BYD, based in Shenzhen, recently surpassed Tesla as the world’s largest manufacturer of electric cars, and CATL, a Chinese rival based in Ningde, produces the most batteries. BYD and CATL have both relied on lithium-ion batteries that use relatively inexpensive iron and phosphate, combined with lithium, rather than nickel and cobalt, which Western producers have favored. Through patented breakthroughs, the Chinese companies made their batteries lighter, longer-lasting, faster to charge and cheaper to produce…

China has nearly 50 graduate programs focused on battery chemistry and metallurgy. According to the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, 65.5 percent of widely cited technical papers on battery technology come from researchers in China, compared with 12 percent from the United States… As of July, Beijing has restricted any effort to transfer out of China eight key technologies for manufacturing electric vehicle batteries, be that through trade, investment or technological cooperation.

6. The Times has a long read on China’s build out of massive solar and wind generation farms in the Tibetan Plateau to harness the high altitude region’s vast deserted plains, brighter sunlight, and windy conditions. It reports that China is building an enormous network of clean energy industries on the world’s highest plateau.

No other country on the planet is using high altitudes for solar, wind and hydropower on a scale as great as China’s on the Tibetan Plateau. The effort is a case study of how China has come to dominate the future of clean energy. With the help of substantial government-directed investment and planning, electricity companies are weaning the country off imported oil, natural gas and coal — a national priority… the Talatan Solar Park, dwarfs every other cluster of solar farms in the world. It covers 162 square miles in Gonghe County, an alpine desert in sparsely inhabited Qinghai, a province in western China… Electricity from solar and wind power in Qinghai… costs about 40 percent less than coal-fired power… has a capacity of 16,930 megawatts of power, which could run every household in Chicago. It is still expanding, adding panels with a target of growing to 10 times the area of Manhattan in three years. Another 4,700 megawatts of wind energy and 7,380 megawatts of hydroelectric dams are nearby…

More than a decade ago, eight dams were built on the Yellow River as it drops 3,300 feet, flowing off the eastern side of the plateau and down into eastern China. More are under construction to balance and supplement the solar energy being generated in Qinghai Province… Two additional hydropower projects are being built in high mountain valleys near the Talatan Solar Park. The plan for both, Qinghai officials said, is to use excess solar power generated during the day to pump water up into the projects’ reservoirs several miles up. The water will be allowed to drop down through mountain tubes to the plateau at night, spinning giant turbines to generate immense amounts of electricity.

Several electricity-intensive industries are moving to the region to tap its inexpensive power. One is the task of turning quartzite from mines into polysilicon to make solar panels. Data centers for artificial intelligence are also drawn to the area. Qinghai plans to increase its data center capacity more than five times by 2030… The data centers consume 40 percent less electricity, their main operating cost, than similar ones at sea level because air-conditioning is barely needed, said Zhang Jingang, the executive vice governor of Qinghai. Air warmed by the data centers’ computer servers is circulated through underground pipes to heat other buildings in Yushu and Guoluo, replacing coal-fired boilers…

High-altitude projects affect relatively few people in sparsely populated settlements. China pushed more than one million people out of their homes in west-central China a quarter-century ago and flooded a vast area for the reservoir of the Three Gorges Dam. This year, China has been installing enough solar panels every three weeks to match the power generation capacity of that dam…

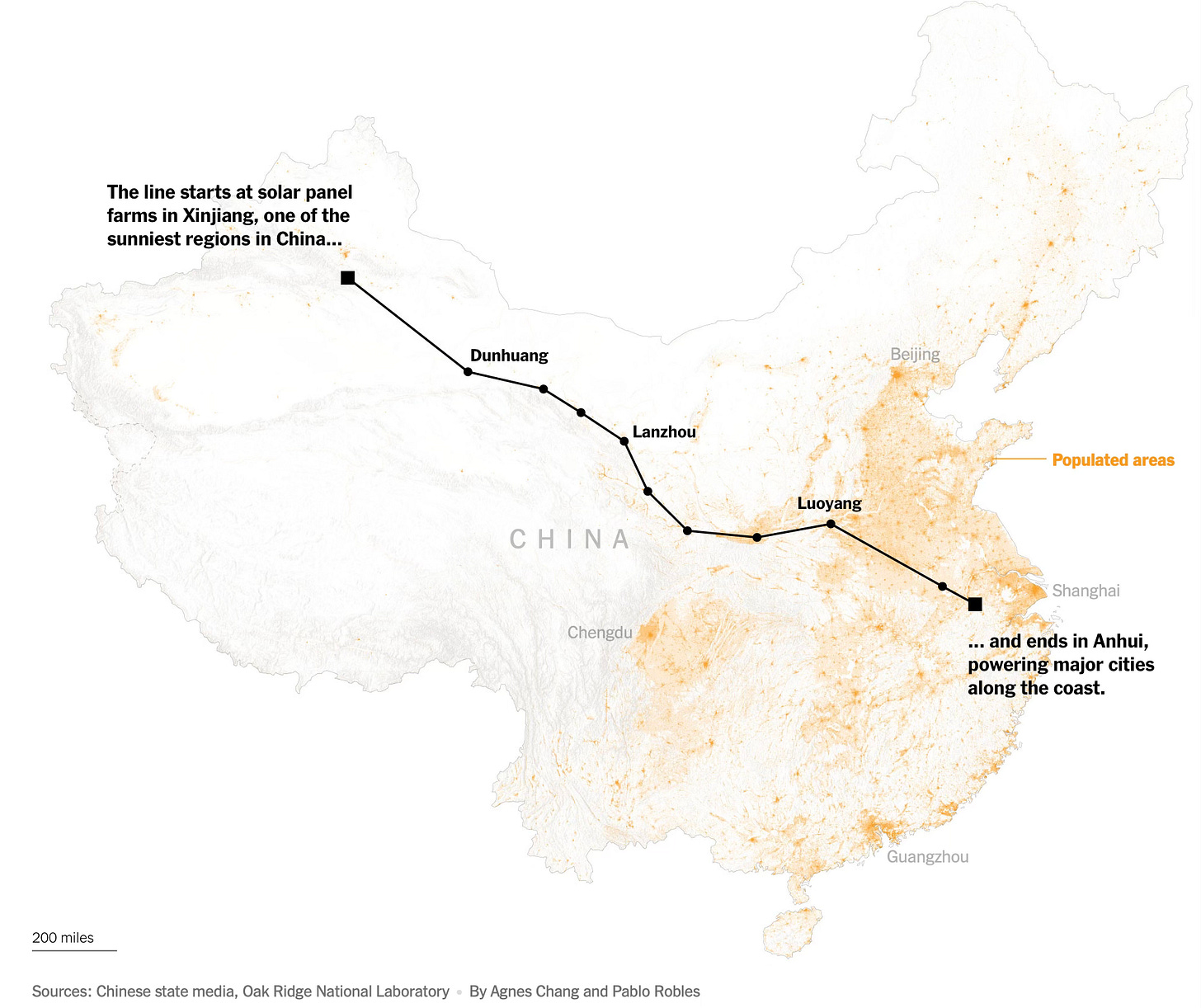

7. Any development of renewable power generation capacity must be complemented with the rollout of requisite transmission capacity.

Another NYT long read describes how China is building ultra-high voltage electricity transmission lines to transport renewable power from its deserted, sunny, and windy north and western regions with their roaring rivers to the cloudy and windless load centres in the east with its sluggish rivers, where 90% of its people lives and which hosts most of the factories. One UHV line stretches 2000 km.

To put this in perspective, in addition to the UHV line shown above, China has 41 others, each capable of carrying more electricity than any transmission line in the US, and uses direct current technology with barely any transmission losses that make them more efficient than transmission lines elsewhere.

The most recent public Chinese data, from the end of 2024, showed 19 lines transmitting power at 800 kilovolts. Another 22 lines operated at 1,000 kilovolts. One of them, the behemoth terminating in Guquan, transmits enough electricity at 1,100 kilovolts to power more than seven million American households or 40 million to 50 million Chinese households… the United States has a handful of 765-kilovolt lines and a few running at 500 kilovolts or less, according to the Electric Power Research Institute, a nonprofit research group. The 765-kilovolt lines together total about 2,000 miles — the length of a single line across China. The Soviet Union built a power line in Central Asia that was designed to operate at 1,150 kilovolts. But it used less powerful equipment and has not run at full tilt for decades.

The development of China’s ultrahigh-voltage lines was given a push in 2009, during the global financial crisis. The central government approved enormous investments in their construction to create jobs and head off an economic slowdown. China’s leaders staked ambitious plans for electric vehicles and high-speed rail lines around the same time. In March 2011, the construction of ultrahigh-voltage lines gained further momentum from the partial meltdown of three nuclear reactors after an earthquake and tsunami in Fukushima, Japan. Beijing delayed many prospective nuclear reactors, which had been planned near cities, and doubled down on transmission lines from remote areas.

Across the world, the biggest challenge to building any transmission lines, much less UHV lines with greater health risks, has been in overcoming opposition from local residents and securing right of way. These lines cause small electric shocks that can potentially have fatal consequences. The article points to people complaining of static electricity preventing them from holding the fishing rod when fishing or the umbrella in rain when near the closely bunched lines. However, the Chinese government, with its top-down industrial planning, has been able to overlook this and quickly proceed with construction.

8. Finally, no article on China today can be complete without its remarkable dominance in rare earth minerals. As it imposed export controls over 12 out of the 17 rare earth elements, this puts their importance in the defence sector in perspective.

In the first week of the Iran-Israel conflict in June this year, approximately 800 missiles were exchanged. Each contained anywhere between two and 20 kilogrammes of rare earth elements, including two, dysprosium and terbium, now subject to Chinese export controls. Based on conservative estimates from the limited data, this means anywhere between 1.6 and 16 metric tonnes of rare earth elements were vaporised in that conflict in seven days. Ukraine’s extraordinary recent performance in its drone war against the Russian invasion is almost entirely dependent on electronics and magnets imported from China. Ukraine is now less concerned about whether European arms deliveries will arrive on time and more worried about the flow of tech imports from China. In the past 30 years, China has become the world leader in the processing of most of the 54 raw minerals that the US Geological Survey classifies as critical for US industry, including the defence sector. Currently the Chinese can process virtually any mineral 30 per cent more cheaply than its competitors.

Rana Faroohar writes about how the US surrendered to China its rare earth refining and processing and magnets manufacturing base.

In 1992, Deng Xiaoping announced the country’s desire to turn rare earths into the “oil” of China. In the mid-1990s, amid a general deregulation of global trade that led to more permissive investment screening and tolerance of offshoring, the US Committee on Foreign Investment in the US, under the Clinton administration, approved General Motors’ sale of Magnequench — an Indiana-based company that manufactured the rare earth magnets used in computer hard drives, consumer electronics and jet guidance systems — to Chinese owners with close ties to Beijing…The Cfius approval was based on a promise that the factory would stay in Indiana. It didn’t. After a few years, the entire Indiana operation was shut down, and production and equipment were moved to China… But it wasn’t only a lead in production that the US willingly gave up — it also failed to protect its access to raw materials. Until the late 20th century, the US was the world’s leading producer of rare earth minerals, mainly through the Mountain Pass mine in California, which opened in 1952. Stricter environmental standards, lower productivity and a lack of support for industrial policy in the US led to its closure in 2002. Mountain Pass was eventually reopened in 2012, but by then the Americans had no domestic refining capacity and had to ship their raw materials to China for processing.