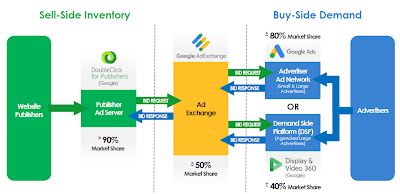

... monopolize the publisher ad server market in the United States... monopolize, or, in the alternative, attempt to monopolize, the ad exchange market in the United States ... monopolize the advertiser ad network market in the United States... tying AdX and DFP.

Order the divestiture of, at minimum, the Google Ad Manager suite, including both Google’s publisher ad server, DFP, and Google’s ad exchange, AdX, along with any additional structural relief as needed to cure any anticompetitive harm; Enjoin Google from continuing to engage in the anticompetitive practices described herein and from engaging in any other practices with the same purpose and effect as the challenged practices; Enter any other preliminary or permanent relief necessary and appropriate to restore competitive conditions in the markets affected by Google’s unlawful conduct.

The suit's argument goes like this,

Every time an internet user opens a webpage with ad space to sell, ad tech tools almost instantly match that website publisher with an advertiser looking to promote its products or services to the website’s individual user. This process typically involves the use of an automated advertising exchange that runs a high-speed auction designed to identify the best match between a publisher selling internet ad space and the advertisers looking to buy it... One industry behemoth, Google, has corrupted legitimate competition in the ad tech industry by engaging in a systematic campaign to seize control of the wide swath of high-tech tools used by publishers, advertisers, and brokers, to facilitate digital advertising. Having inserted itself into all aspects of the digital advertising marketplace, Google has used anticompetitive, exclusionary, and unlawful means to eliminate or severely diminish any threat to its dominance over digital advertising technologies.Google’s plan has been simple but effective: (1) neutralize or eliminate ad tech competitors, actual or potential, through a series of acquisitions; and (2) wield its dominance across digital advertising markets to force more publishers and advertisers to use its products while disrupting their ability to use competing products effectively... Google, a single company with pervasive conflicts of interest, now controls: (1) the technology used by nearly every major website publisher to offer advertising space for sale; (2) the leading tools used by advertisers to buy that advertising space; and (3) the largest ad exchange that matches publishers with advertisers each time that ad space is sold. Google’s pervasive power over the entire ad tech industry has been questioned by its own digital advertising executives, at least one of whom aptly begged the question: “[I]s there a deeper issue with us owning the platform, the exchange, and a huge network? The analogy would be if Goldman or Citibank owned the NYSE.”By deploying opaque rules that benefit itself and harm rivals, Google has wielded its power across the ad tech industry to dictate how digital advertising is sold, and the very terms on which its rivals can compete. Google abuses its monopoly power to disadvantage website publishers and advertisers who dare to use competing ad tech products in a search for higher quality, or lower cost, matches. Google uses its dominion over digital advertising technology to funnel more transactions to its own ad tech products where it extracts inflated fees to line its own pockets at the expense of the advertisers and publishers it purportedly serves.Google’s anticompetitive behavior has raised barriers to entry to artificially high levels, forced key competitors to abandon the market for ad tech tools, dissuaded potential competitors from joining the market, and left Google’s few remaining competitors marginalized and unfairly disadvantaged. Google has thwarted meaningful competition and deterred innovation in the digital advertising industry, taken supra-competitive profits for itself, and prevented the free market from functioning fairly to support the interests of the advertisers and publishers who make today’s powerful internet possible.The harm is clear: website creators earn less, and advertisers pay more, than they would in a market where unfettered competitive pressure could discipline prices and lead to more innovative ad tech tools that would ultimately result in higher quality and lower cost transactions for market participants. And this conduct hurts all of us because, as publishers make less money from advertisements, fewer publishers are able to offer internet content without subscriptions, paywalls, or alternative forms of monetization. One troubling, but revealing, statistic demonstrates the point: on average, Google keeps at least thirty cents—and sometimes far more—of each advertising dollar flowing from advertisers to website publishers through Google’s ad tech tools. Google’s own internal documents concede that Google would earn far less in a competitive market.

Google corners 35 cents of each advertising dollar that flows through its Ad-tech tools!

The scale of monopoly power and its pervasiveness across the entire chain is staggering

Bloomberg has a good summary article. See also this.

Section 19a prohibits conduct in areas where platforms are not yet dominant and leaves the door open to tackling future anti-competitive behaviour that has not yet been identified. If companies are ruled to be of “paramount significance for competition across markets”, then the regulator can prohibit them from ranking their own services ahead of rivals, from denying rivals access to data, and from preventing users from taking their own data to other competing services. Since Section 19a came into effect, Germany’s antitrust watchdog has opened high-profile investigations against the world’s largest tech companies. The Federal Cartel Office’s investigation into whether Facebook grants an unfair advantage to users of its social network platforms on its VR glasses has already brought benefits to consumers, even as it continues. The German watchdog has ensured users can use the headsets without a Facebook or Instagram account. It is also investigating Google Maps over potential anti-competitive restrictions to the detriment of rivals and opened two separate probes into Amazon’s marketplace practices over concerns that the platform is disadvantaging the position of third-party sellers.