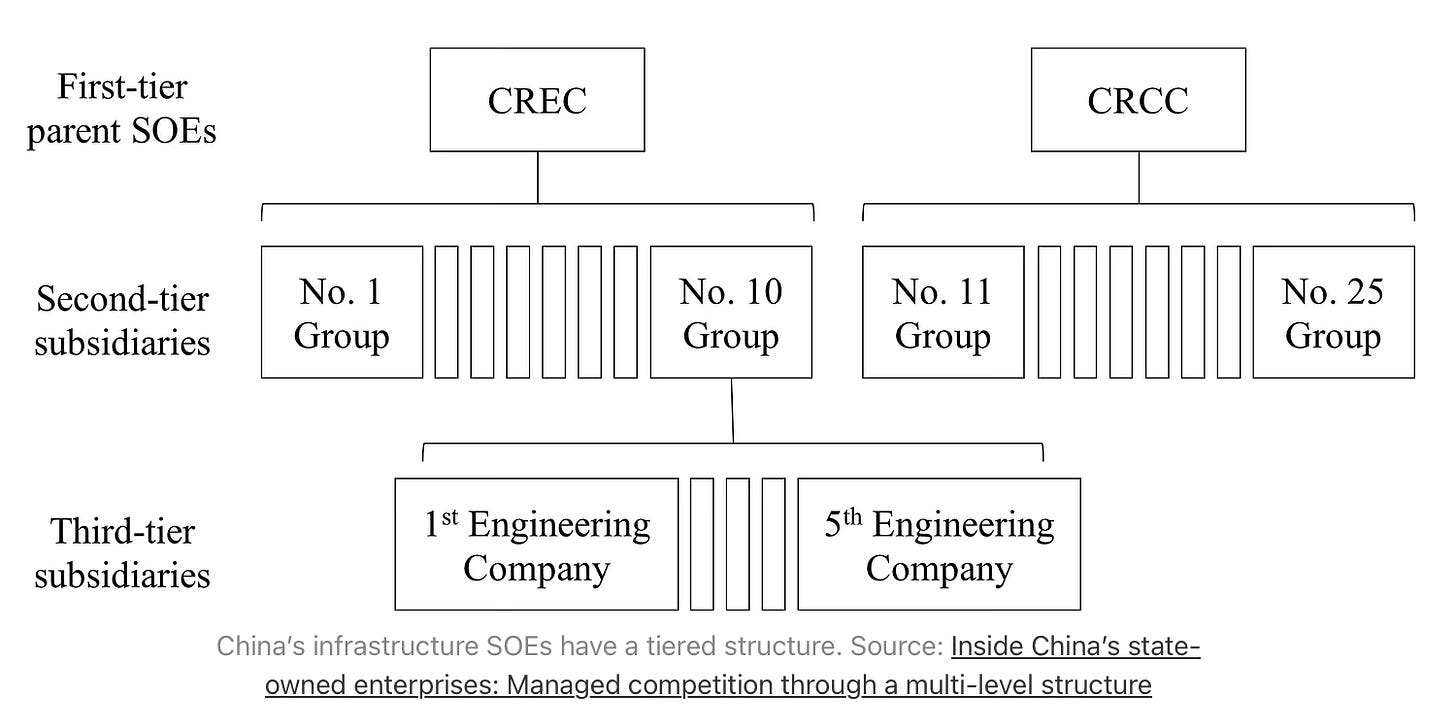

In the eye of the storm is the proposal to raise the provision requirement by more than 12 times – from 0.4 per cent to 5 per cent of the outstanding as well as fresh exposure during the construction phase of a project. Once a project reaches the operational phase, the provision can be halved to 2.5 per cent. It will be reduced further to 1 per cent when the project’s cash flow can meet the repayment obligation to all lenders, and the long-term debt of the project declines by at least 20 per cent when it starts commercial operations. The rationale behind such a measure could be that lenders have been evergreening their exposures to under-construction and delayed infrastructure projects. The 5 per cent provisioning during the construction will be achieved in a phased manner: 2 per cent by March 31, 2025 (spread over the four quarters of 2024-25); 3.5 per cent by March 31, 2026 (spread over the four quarters of 2025-26); and 5 per cent by March 31, 2027 (spread over the four quarters of 2026-27)... Typically, the return from such projects for the lenders is around 9 per cent and, for the investors, it’s around 15 per cent. The debt-to-equity ratio for infra projects varies, depending on its nature, but roughly 70:30 is the norm... With the rise in the cost of money, the cost of loans for project finance will rise as no lender would like to compromise on profitability. Analysts predict the impact could be between 0.5 and 0.7 per cent, depending on the balance sheets of the lenders.

2. Interesting observation by Janan Ganesh

Dissent is core to financial success. Why buy an asset unless you think the market has underpriced it? Why set up a business unless you think the world is wrong not to have offered that product or service already? Opening the humblest corner bistro is, in essence, a statement that everyone who hasn’t opened one there has missed a trick. Imagine how much stronger that contrarian impulse must be in a hedge fund seeking above-market returns.All power to this attitude. The world would be less prosperous without it. But it doesn’t transfer well to public life. In politics, if you support a radical proposition and turn out to have misjudged it, the consequence might be, oh I don’t know, societal ruin. (Or deaths in the Capitol.) There is no equivalent of limited liability. There is no equivalent of the circuit breakers that the state puts in place to contain bad business bets. The state itself is on the line.

3. Akash Prakash has this view on foreign portfolio investments in India.

The fact is that for the last 2.5 years, the net flow of foreign portfolio investors’ money into India has been zero. India is now at best a neutral weight for most emerging markets investors, having always been an overweight historically. For those allocators who were smart enough to have been in India early, they are rebalancing from the country and taking profits. For new flows, we will have to look at the global funds, which have not been in India historically or took profits much earlier. India’s continuously rising weights make it harder to totally ignore. Until markets catch a breath and consolidate for some time, I don’t think we can expect large foreign flows. The longer-term intention remains to raise weights in India, but there seems to be no urgency. Foreign capital continues to wait for the correction, which surging domestic flows do not allow to happen.

4. Good article on the gravitation of Indian automakers towards hybrid cars and the slowing down of their EV ambitions.

5. Changing trends in the insurance industry as insurers try to shift from "repair and replace" to "predict and prevent" model of insurance management.

Auto insurers opened the door a decade ago, by offering lower premiums to customers who installed data recorders, known as telematics, in their cars to monitor their driving. Since then, cheaper digital sensors and improved analytics have allowed insurers to step up from tracking to advice and even outright intervention. State Farm offers homeowners free smart plugs that constantly check for electrical faults. Chubb bought a company that makes leak detection systems and offers discounts to homeowners who install them. Manulife first used fitness trackers to monitor customers of its John Hancock Vitality life insurance and reward them for physical activity with prizes as well as lower premiums. But its efforts to nudge customers towards longevity now run the gamut from discounts on fruits and vegetables, to cancer screening and whole-body MRI scans... Corporate insurers are also now helping clients identify and reduce risk. They hope this will take the sting out of rising premiums and generate consulting fees. Chubb sends inspectors armed with infrared cameras to commercial buildings to look for electrical system weaknesses. Zurich advises property owners on how to install rooftop solar panels to minimise future wind and fire damage. It also helps manufacturers guard against product liability claims by advising on quality control programmes.

6. Noice interactive graphic that informs the trajectory of inflation in the US since the pandemic.

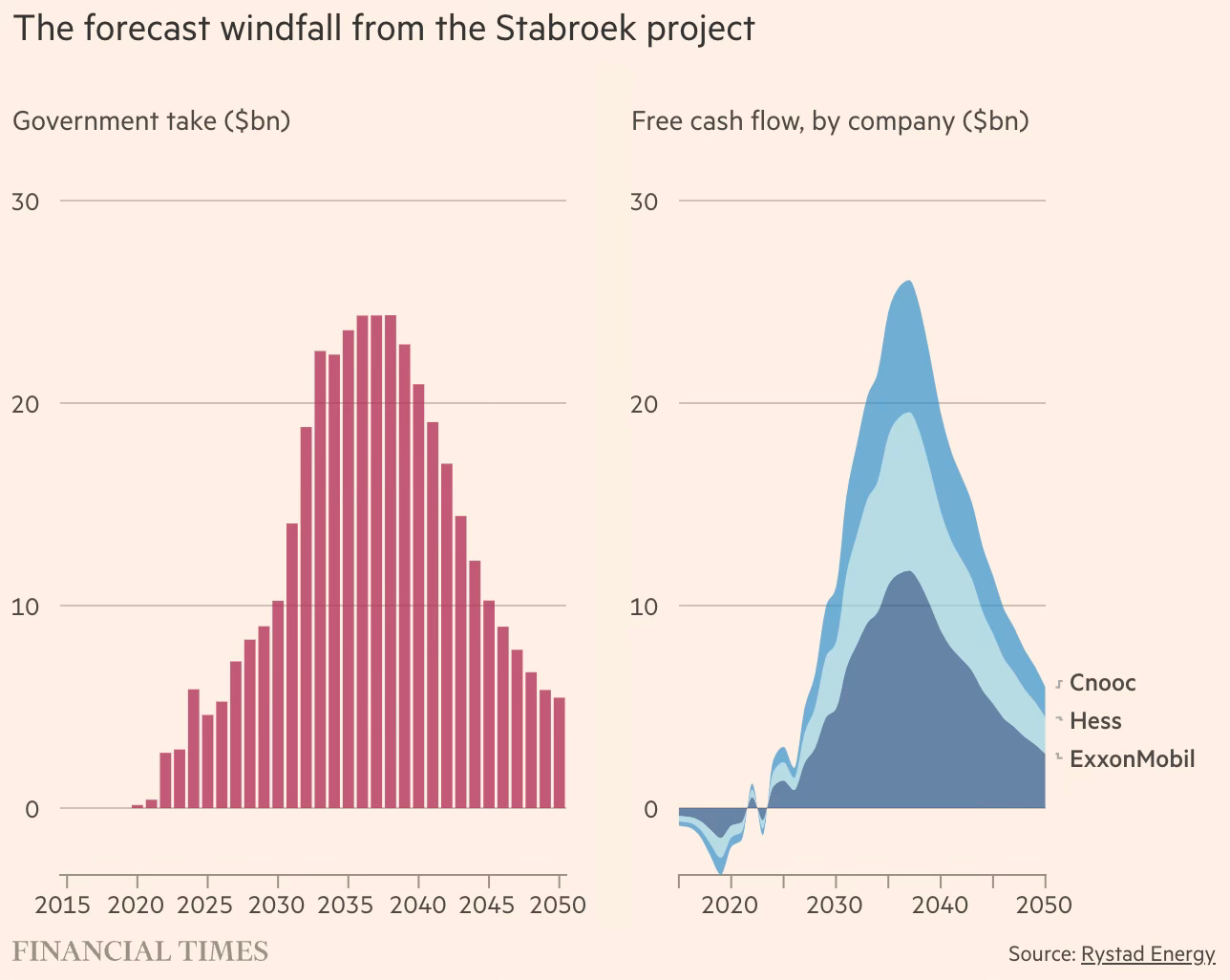

7. Good example of PPPs

The Taj Mahal Hotel of Delhi is a good example of public-private partnership (when the phrase had not yet come into usage) where the New Delhi Municipal Council and Delhi Development Authority provided land and the building structure with the Tatas investing in finishing and furnishing and entering into a long-term revenue sharing contract. These were highly profitable investments for both sides.

8. The volatility in Nvidia's prices is striking

More than 200 companies, or roughly 40 percent of the stocks in the index, are at least 10 percent below their highest level of this year. Almost 300 companies, or roughly 60 percent of the index, are more than 10 percent above their low for the year. And each group includes 65 companies that have actually swung both ways. Traders say this lack of correlated movement — known as dispersion — among individual stocks is at historic extremes, undermining the idea that markets have been blanketed by tranquillity... So even on a day like Monday, when Nvidia slumped 6.7 percent, the S&P 500 dropped only 0.3 percent. The broad index was buttressed by other stocks, especially other mammoth technology companies like Microsoft and Alphabet... The options market has ballooned — the number of contracts traded is set to exceed 12 billion this year, according to Cboe, up from 7.5 billion in 2020 — and while there have always been specialists with wonky derivatives strategies, now more mainstream fund managers are said to be piling in. Assets in mutual funds and exchange-traded funds that trade options, including trading dispersion, swelled to more than $80 billion this year, from around $20 billion at the end of 2019, according to Morningstar Direct.

This presents both opportunities and dangers.

This is presenting an opportunity for Wall Street, as investment funds and trading desks pile into dispersion trading, a strategy that typically uses derivatives to bet that index volatility will remain low while turbulence in individual stocks will stay high... The risk to investors is that stocks will again begin to move in the same direction, all at once — most likely because of a spark that ignites widespread selling. When that happens, some fear, the role of complex volatility trades could reverse and, rather than dampen the appearance of turbulence, exacerbate it.

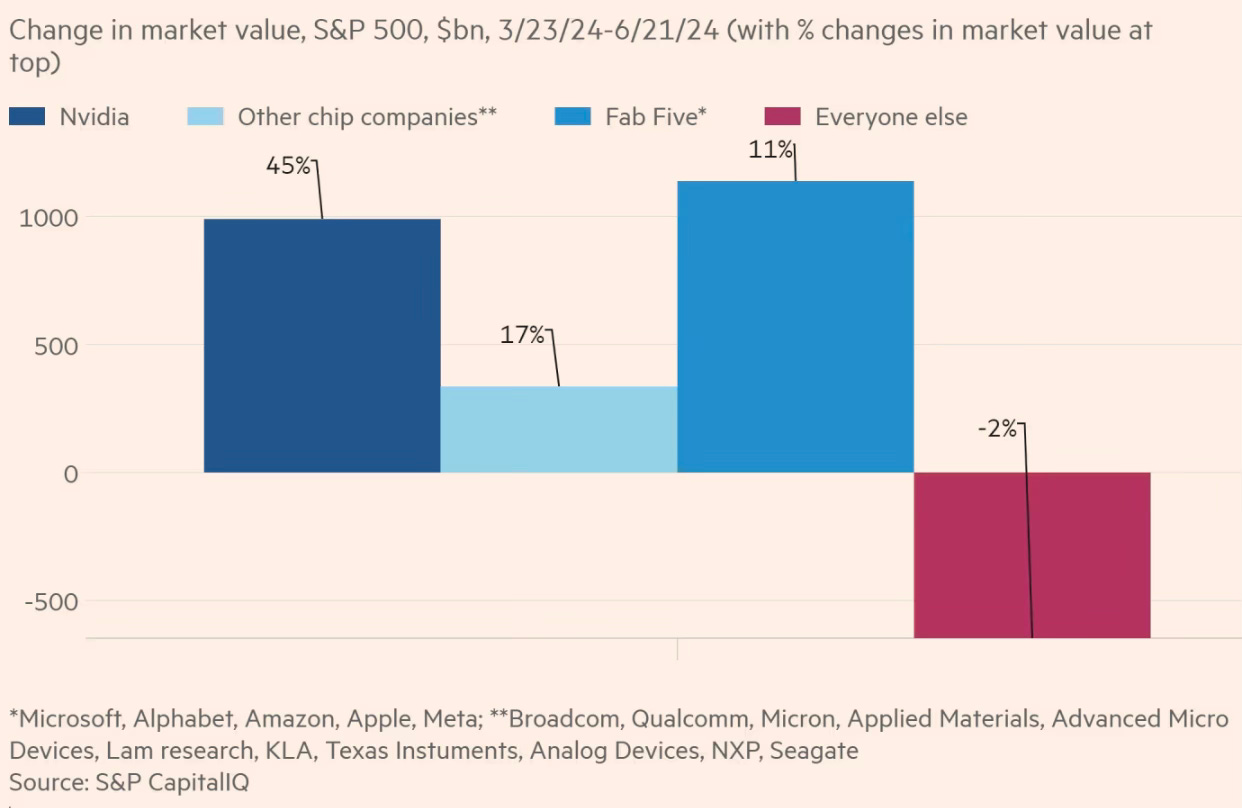

9. More on Nvidia. FT points to the fact that all the gains in S&P 500 since late March has come from AI or AI-adjacent stocks.

In the same period, the non-AI stocks are down 2%, with 9 out of 11 sectors are down.

It's hard for anyone to make informed choices. Consider both the bullish and bearish of views on Nvidia.

Consensus estimates for revenue growth for next year and for 2026 do not, in fact, seem wildly demanding. Analysts are expecting a 23 per cent annual growth rate for Nvidia over that period. This would represent something of a moderation in rate; over the past five years Nvidia revenue has grown at 50 per cent a year. Similarly, the two-year revenue growth rates pencilled in for the Fab Five are at or below the growth rates of recent history. It is only a handful of the chip stocks — Micron, Texas Instruments, Analog, and Lam — where a major acceleration in revenue is expected. Is the recent rally in the AI group driven by upgrades of earnings estimates? Looking at 2025 estimates, not really. Since the end of March, earnings estimates for the group as a whole have crept up in the low single digits, percentage wise. Apple, Amazon, and Micron are the only ones that have received meatier upgrades... In the past three months, the price/earnings ratios of Nvidia, Apple, Broadcom, and Qualcomm have all risen by over 20 per cent. Looking back to last October, when the rally began, the average (harmonic mean) P/E ratio in the AI group is up almost 50 per cent.

Unhedged also points to the internal tension within the AI rally

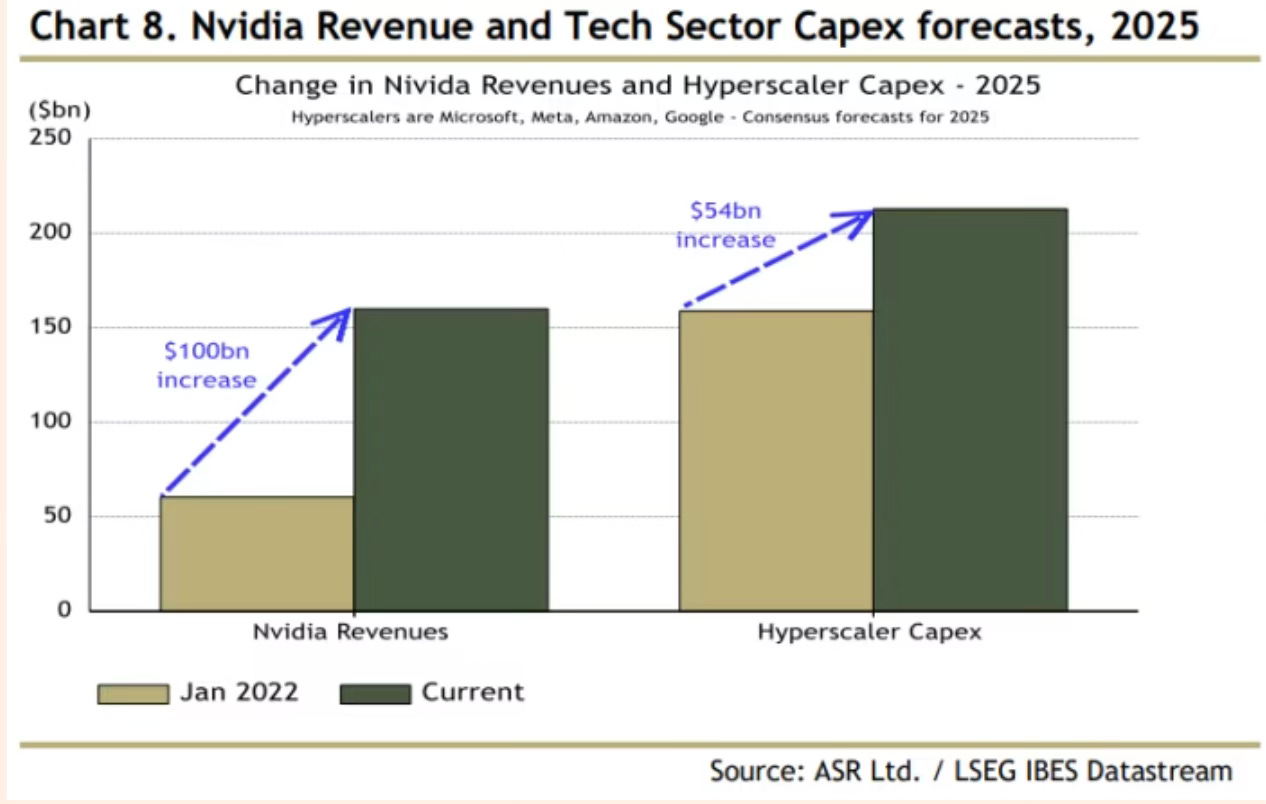

One internal tension within the AI rally is that the revenues of its leading company, Nvidia, are expenses for some of its biggest beneficiaries, the Fab Five. In the short term, Nvidia’s success is a drag on the cash flows of Big Tech companies, which are buying the bulk of Nvidia’s chips. Charles Cara of Absolute Strategy Research has recently made a provocative point about this. He notes that 40 per cent of Nvidia’s revenues come from Microsoft, Meta, Amazon, and Google, and that even the very large expected increase in capital expenditure at those companies is not very large relative to the expected increase in Nvidia’s revenues. The increase in the four companies’ capital spending between the last fiscal year and 2025, at $54bn, is more than 40 per cent of the $100bn expected increase in Nvidia’s revenues, but presumably only a fraction of Big Tech’s capital spending goes to Nvidia’s GPUs. So either the Big Tech will spend more, or Nvidia will make less.

Here's Robert Armstrong's conclusion in interpretation of the spectacular rally.

Perhaps it just reflects momentum and animal spirits. More charitably, it could reflect the expectation that the AI business will provide an increase in profits that lasts for many years into the future. That is to say, it is a bet about the competitive dynamics within the AI industry: that it will not be hypercompetitive, and the winners in the long term will be the same as the winners now — the Fab Five and today’s leaders in the semiconductor industry. To me, the second half of the bet, that the incumbents will keep on winning, seems like a reasonable one. Incumbency in tech is very powerful, to the extent that companies can use their strong market position in one technology to create a strong position in another (think of Microsoft moving from PC operating systems to cloud computing). The first half of the bet, that AI will not turn into a capital-intensive knife fight where no one makes high profits, I don’t know how to assess.

10. Simon Kuper makes an interesting point about why there's so much disillusionment about France about its economy despite the economic health of the country being at its best in decades.

France has western Europe’s largest territory. Millennia of small farming ended here in a few confusing decades. Today LVMH exports more than all of French agriculture. The consequence: most French towns and villages outside tourist hotspots have lost their reason to exist. If they weren’t already there, nobody would now build them. They are shedding shops, schools and doctors. Places without post offices and train stations are statistically more likely to vote far right, because residents feel abandoned by the Republic. Workers have moved to cities, especially Paris. The EU’s biggest international metropolis is another French asset, but inside France it stands for arrogance and wealth, embodied by Macron. There’s an obvious solution: encourage hybrid working, which would let people leave cities for France’s plethora of cheap charming places near TGV stations.

The article also has a case for nuclear energy

Thanks to its nuclear power stations, France produces electricity with the lowest carbon intensity of any large economy, calculates energy think-tank Ember.