I had blogged here arguing that the availability of adequate and good-quality power is the biggest constraint to Africa’s sustained economic growth.

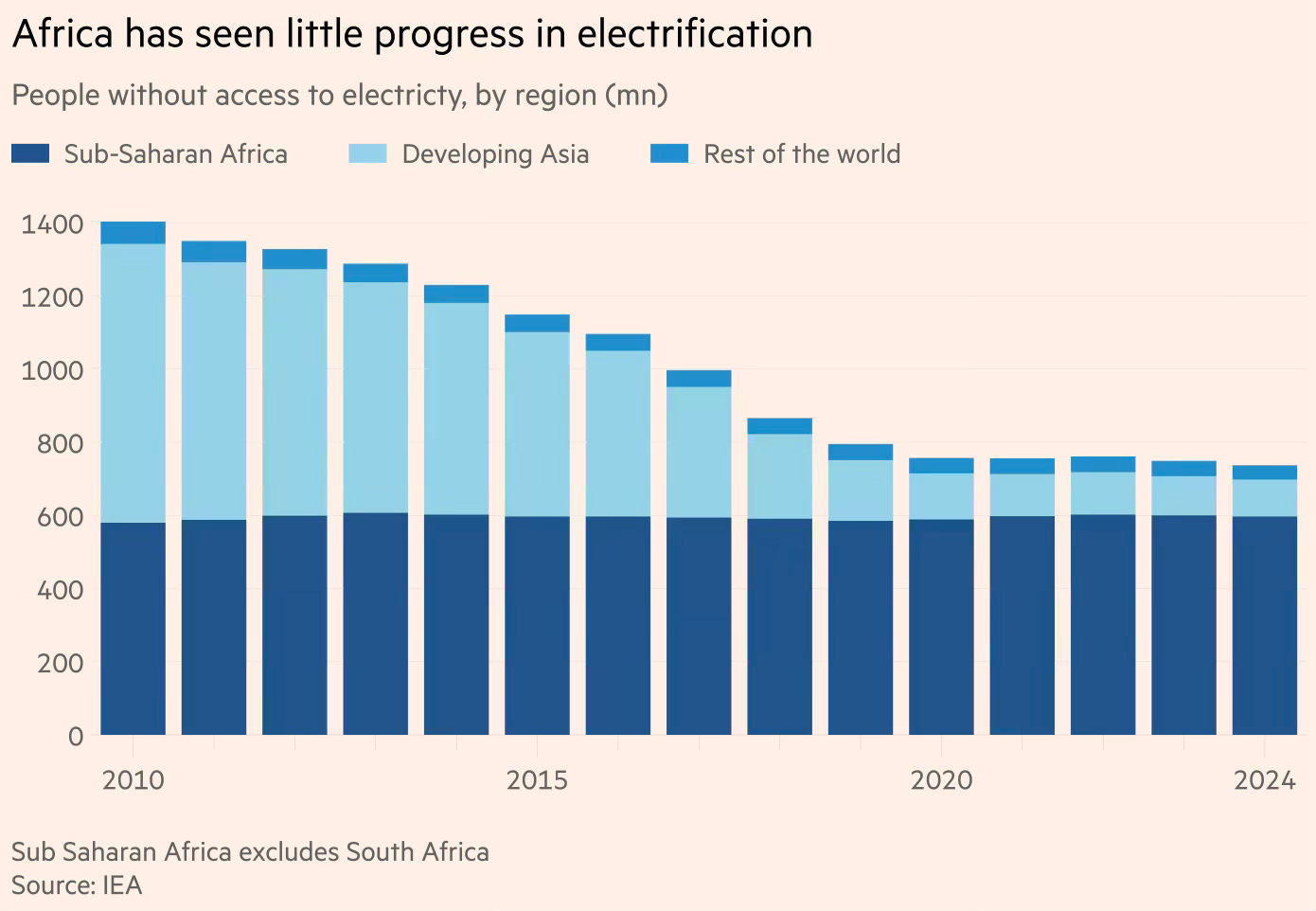

The graphic below is a powerful illustration of one of the biggest failures of global development efforts.

The number of people in Africa without access to electricity remains at 600 million, unchanged from 15 years ago. Among those without electricity globally, the share of Africans has risen from a third in 2010 to 80% in 2024.

Africa’s electrification problem seems to be excessively concentrated in its hinterland areas, in the region sandwiched between the North and the South.

In this context, it’s also useful to see the contrasting fortunes of South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa in electrification.

Africa has had a very low baseline of electrification. For example, SSA reached South Asia’s 1995 level of electrification only by 2020, despite its percapita GDP in 2020 being 2.34 times more than that of South Asia in 1995. East Asia and Latin America had a much higher baseline of electrification than even South Asia. This questions an oft-repeated argument that Africa will be able to afford high electrification rates only if its incomes rise enough to sustain a viable market.

I’m inclined that a very big reason for the gap is the governance of the electricity supply. Through a series of reforms, South Asia, especially India, managed to restructure the sector, regulate it more effectively, improve operational efficiencies of state utilities, and gradually bring in consumer payment discipline. The industrial, commercial, and other higher consumption subscribers were able to ensure that the discoms could become viable entities even after subsidising the vast majority of residential consumers. All this, in turn, derisked the sector and opened the door for private investments in generation.

The take-off point for electrification in India was the Electricity Act 2003, one of the least appreciated among India’s economic reforms. Today, almost all incremental generation capacity addition from all sources comes from the private sector, and it owns more than half the total installed capacity, from virtually zero at the turn of the millennium. Domestic promoters and capital, intermediated mostly by regular banks, have been the major financiers.

Africa too must go through these reforms if it’s to derisk its electricity sector and make it viable enough for private investments into generation. In most African countries today, it appears futile to rely on private financing in any meaningful manner to meet power generation requirements. I had blogged here, highlighting the challenges with attracting private investments into power generation in Africa. Till then, public financing may have to do the heavy lifting on electrification in Africa.

In the spectrum between public and private goods, electricity is an interesting outlier. While it’s a private good insofar as people pay for access, power itself has several positive externalities in human resource development and economic growth. In fact, reliable three-phase electricity is one of the most essential preconditions for economic growth. Public production and provisioning of electricity may, therefore, be an unavoidable necessity in Africa for the foreseeable future.

In this context, South Africa’s recent success with reforming its electricity sector and reviving Eskom after numerous scandals and rolling power cuts for several years offers an encouraging sign.

In the latest global endeavour to electrify Africa, the World Bank and the African Development Bank have launched a $90 billion scheme to bring electricity to 300 million people in Sub-Saharan Africa by 2030. About 30 countries have already signed ‘energy compacts’ under the Mission 300 initiative.

A cursory reading of the Mission 300 plan reveals a mix of objectives thrown in under the broad umbrella of electrification - promotion of renewable energy, decentralised and distributed generation, supply through mini and micro-grids, private participation, complex financial instruments, partnerships between DFIs and philanthropic foundations, microentrepreneurs, etc. In simple terms, the objective of electrification is being pursued through private participation, foreign funding, and renewable energy generation. There are several problems with this approach.

For a start, it’s the classic “everything bagel” development, where multiple laudable objectives are being sought to be achieved in the guise of electrifying Africa. Each of these objectives is challenging by itself, and bundling them only makes the objective of electrification in Africa manifold and daunting.

The involvement of several partners in the coalition, while laudable, also risks diffusing accountability and responsibilities. Given the scale of the problem, the role of philanthropies and impact investors is marginal. Even meaningful private investments will be difficult to realise in most countries, especially in the early stages. Given the requirements, small renewable energy units and mini grids are marginal compared to thermal generation and grid supply. As the long history of infrastructure financing in low-income countries shows, complex financial instruments will struggle to make any headway.

Importantly, the opportunity cost of coal (and rivers) rich Africa foregoing thermal (and hydel) power and relying on intermittent solar or wind power is considerable. Besides, given the commercial risks involved, the total cost of renewable power generation by the private sector (including the cost of capital and storage) is likely to far exceed pithead thermal and hydel generation that’s possible in many African countries. In the first stage, it may be useful to prioritise projects with a demand mix that primarily serves industrial and other bulk consumers. The Mission 300 should prioritise all such projects.

The quantum of funds required means that the major share of financing must come from national governments and traditional bilateral and multilateral DFIs through grants and concessional loans. Unless this fundamental constraint is relaxed, the rest are only distractions in the serious endeavour of significantly increasing electrification in Africa.

No comments:

Post a Comment