It has become a feature of economic policymaking to define thresholds for fiscal prudence and macroeconomic stability. Accordingly, it is held that fiscal deficits should not exceed 3% of GDP, public debt should not exceed 60% of GDP, inflation should not exceed 2% (or 4%), etc.

I have blogged earlier here and here about the problems with the uniform adoption of such targets.

This post will examine India’s macroeconomic record over the last fifty years against these benchmarks. It will use data for 1975-2024 from the World Bank’s WDI to assess the impacts of CPI inflation, central government debt (% of GDP), fiscal deficit, and gross fixed capital formation (GFCF) on GDP growth rates.

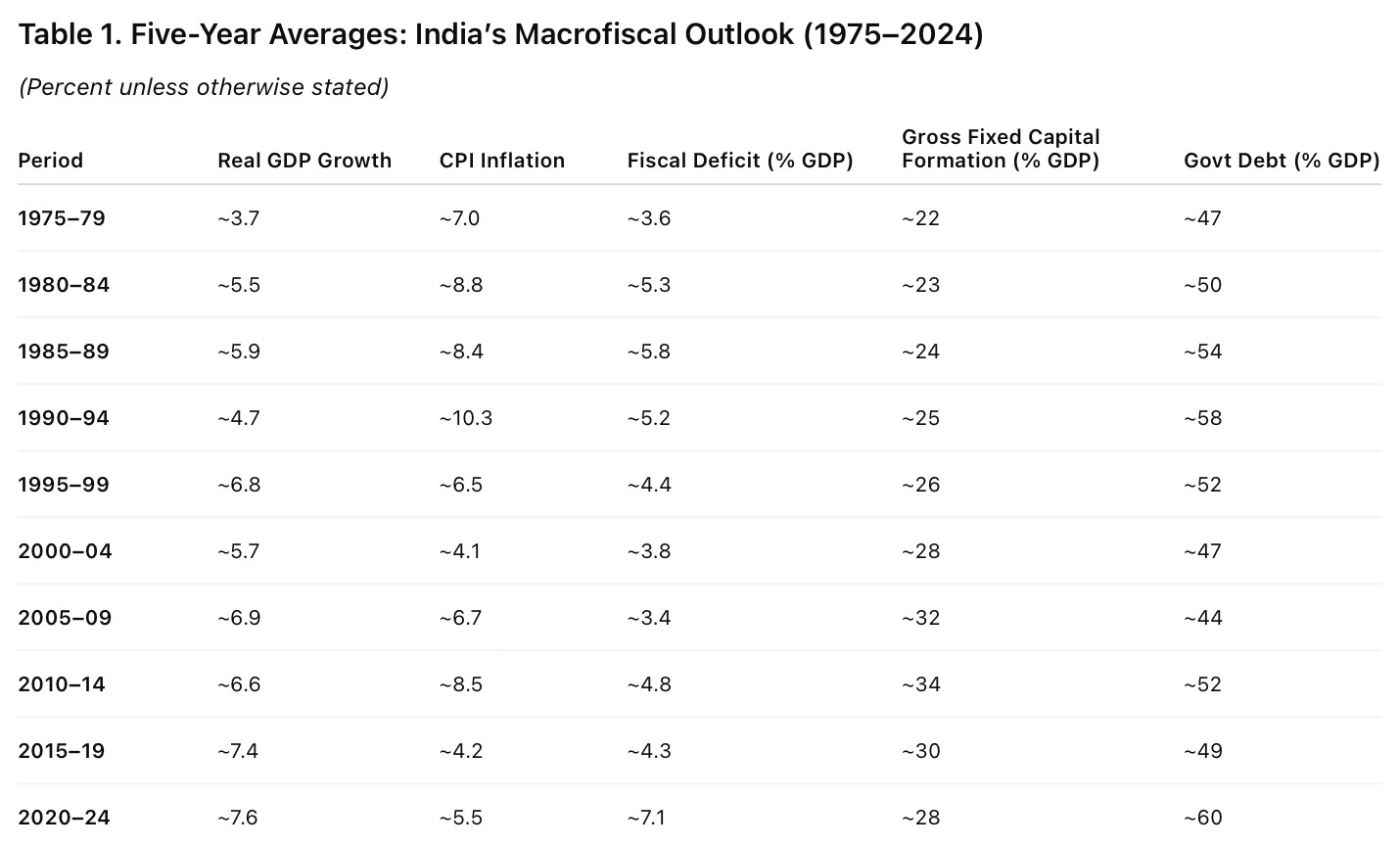

The table below captures the five-year averages on each of the above parameters.

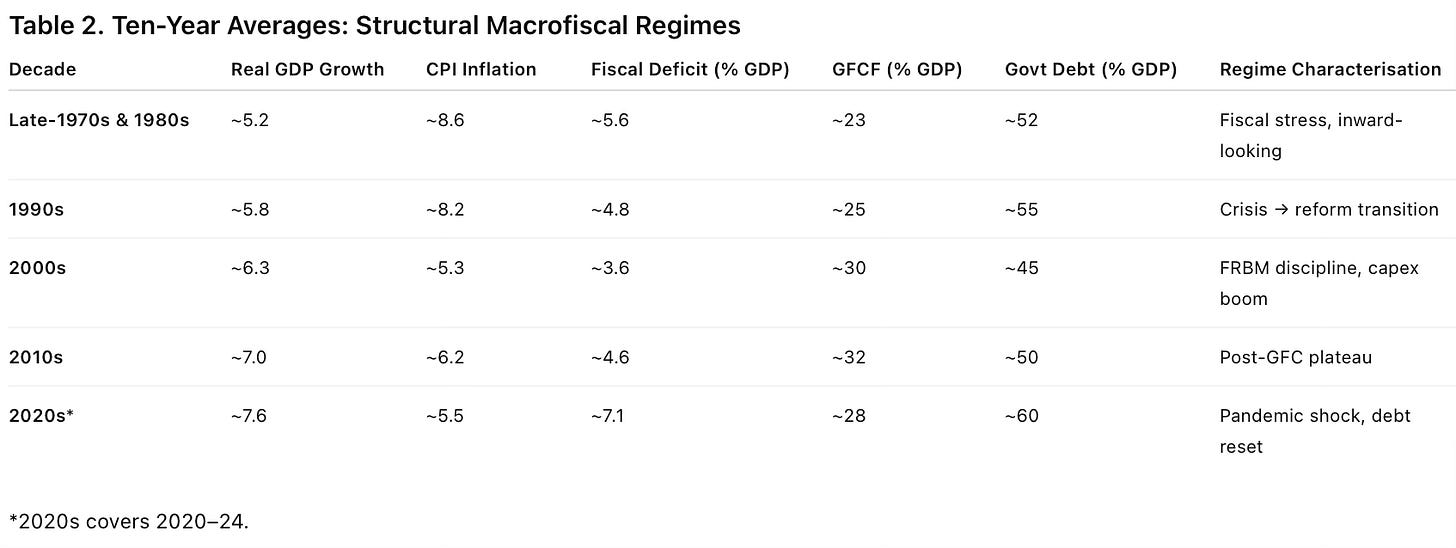

This is the same table with ten-year averages.

This is a ChatGPT summary which broadly conforms to the economic orthodoxy on macroeconomic stability.

A five- and ten-year view of India’s macrofiscal indicators highlights a clear structural shift after the mid-1990s, marked by lower inflation, higher investment, and improved growth outcomes. The FRBM period stands out as the most balanced macro regime. However, major shocks since 2008—particularly the COVID-19 pandemic—have resulted in persistently higher fiscal deficits and public debt, underscoring the importance of restoring fiscal space while protecting capital expenditure.

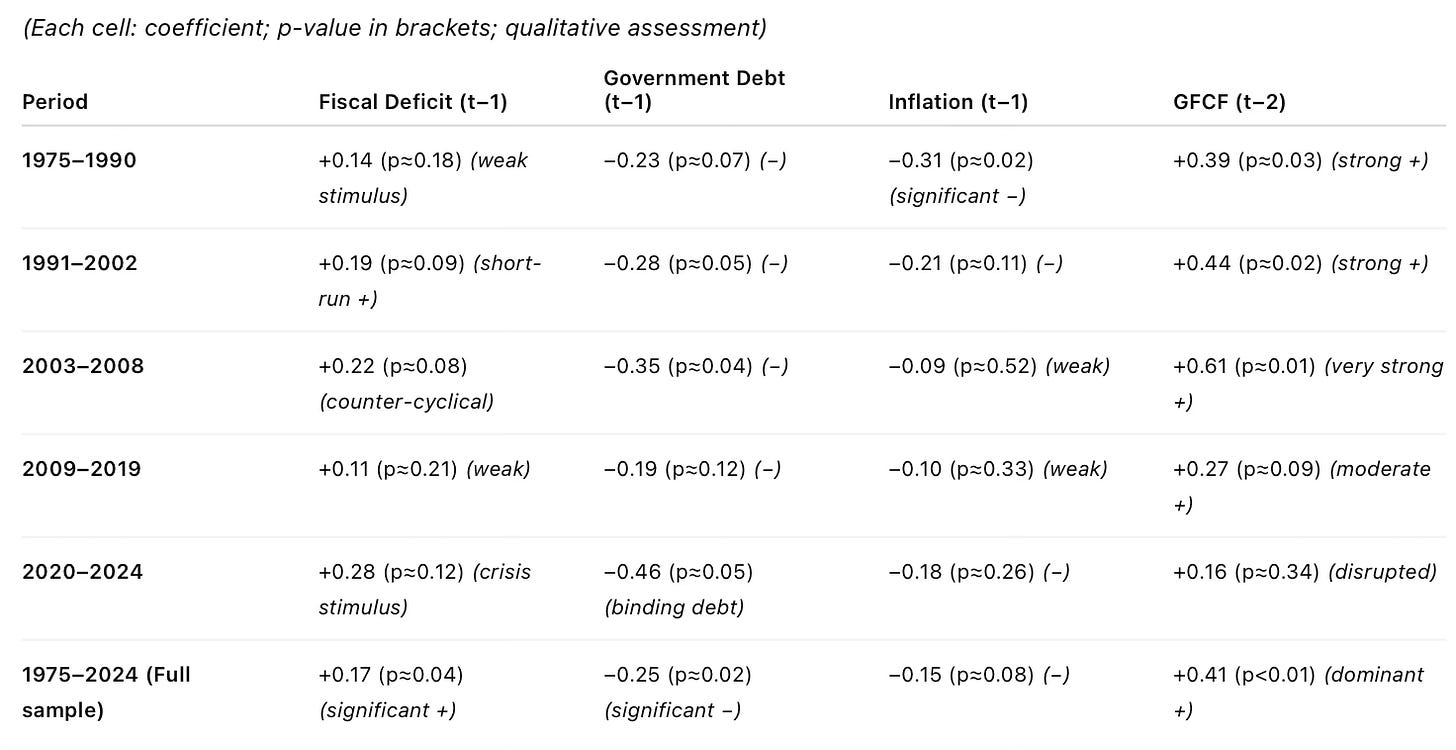

We get broadly similar conclusions from models with different specifications (lagged multivariate growth regression, structural break regression, and reduced-form VAR).

India’s growth experience shows that fiscal deficits support growth only in the short run and only when macro-credibility is intact. Sustained growth is driven far more by investment and macro-stability than by deficit expansion, while rising public debt increasingly constrains long-term growth.

However, if we disaggregate the fifty years into identifiable macroeconomic regimes and perform lagged GDP growth regressions against each parameter separately, the shorter-term trends become less clear and regime-dependent. It provides some useful takeaways.

There are some distinct takeaways. The strongest relationship is that between GFCF and growth. It holds in both short and long-run time frames.

The short-run relationship with fiscal deficits is generally positive. However, the magnitude of this relationship depends on the regime. As can be expected, the three periods with the greatest perceived thrust on macroeconomic stability - post-liberalisation decade, FRBM era (2003-08), and post-Covid 19 years - are also associated with the highest positive impulse from fiscal deficits.

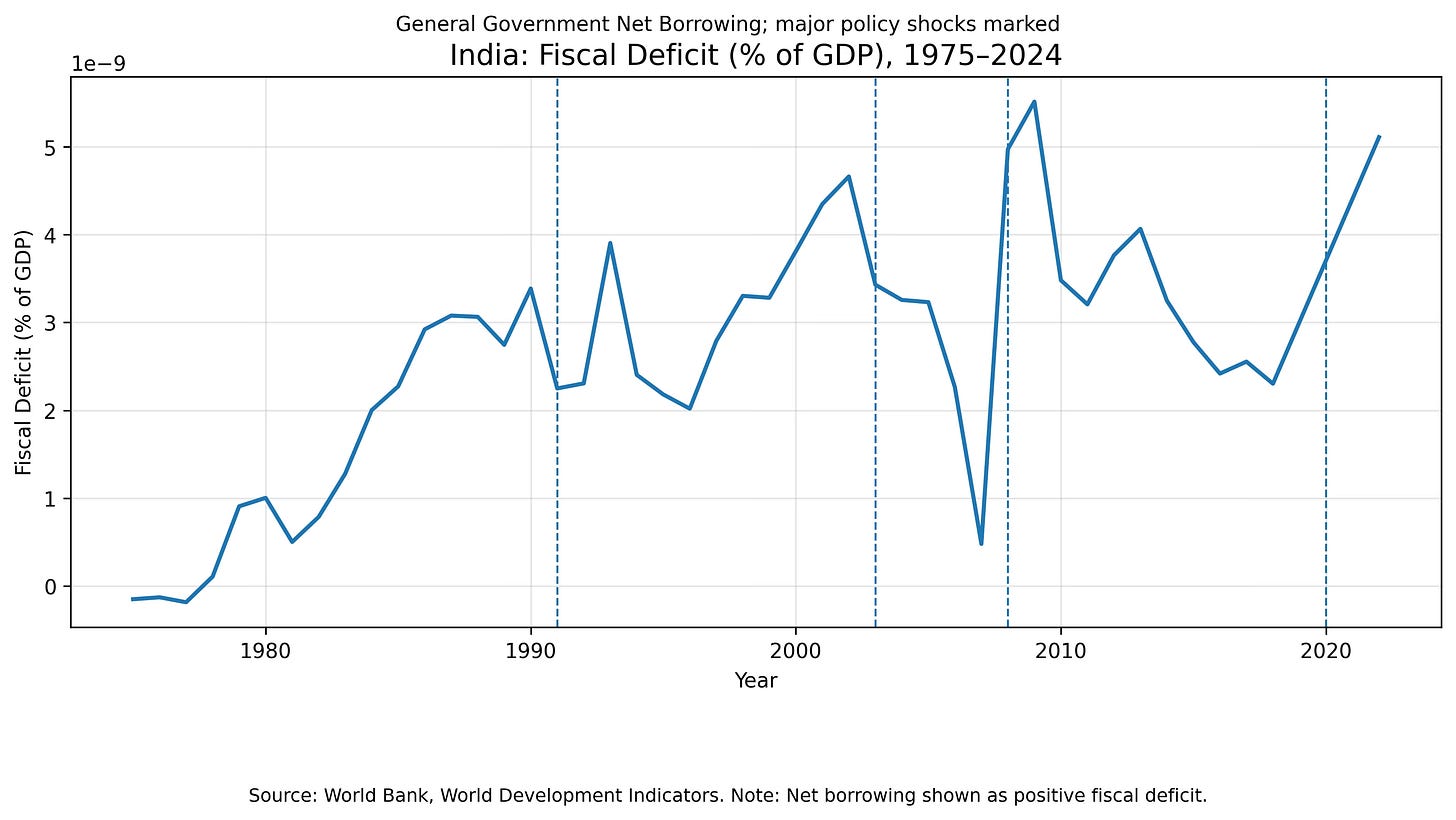

The trends on fiscal deficit show a distinct shift towards a higher deficit. Interestingly, though the post-pandemic period has had the highest deficits, it has also been associated with the highest economic growth rates.

In fact, since 2010, the economy has shifted to a regime with fiscal deficits that are much above the 3% of GDP threshold. But it does not appear to have adversely impacted growth rates, nor market perceptions. An obvious reason is the quality of fiscal deficits, which have shifted sharply towards capital expenditures.

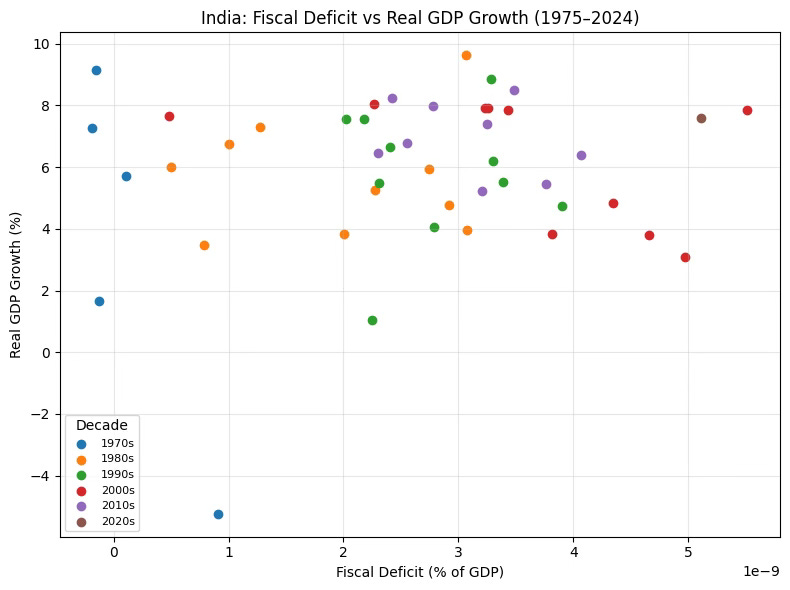

Overall, as the graphic below shows, there’s a very weak correlation between growth and fiscal deficit. At least, there’s nothing to suggest a fiscal deficit threshold around 3% of GDP.

Since around 1995, successive governments in India have generally exercised fiscal prudence in terms of the public debt to GDP ratio being range-bound in the 45-50% range. However, unlike fiscal deficit, there’s a strong inverse correlation between the stock of public debt and GDP growth rates. Therefore, the rise in the public debt ratio in the post-pandemic period should be a matter of concern. When the state government debt is added, the gross public debt is inching towards 100%, easily the highest among all major developing countries.

Similar to fiscal deficit, inflation higher than the target rates has been found to co-exist with high growth rates. There’s little relationship between an inflation rate of 2%, or even 4%, and GDP growth rates. In general, inflation effects tend to weaken once macro stability is achieved.

Over the last decade, India has significantly improved its economic attractiveness. This has come about through a combination of political stability, large infrastructure investments, expansion in the IT services market (GCCs), the emergence of e-commerce and startups with the resultant job creation, gradual but consistent pursuit of economic reforms, interspersed with some critical reforms, and generally good macroeconomic governance through fiscal discipline, quality of public expenditures, and transparency. It has also helped that the country has been growing at steady high rates, and has emerged as the fourth biggest economy in the world and is one of the few big growth markets.

All this has provided the fiscal credibility to run a higher level of deficits. In fact, the Indian economy has benefited from the free lunch of an additional 2-3 percentage points of GDP of fiscal space for the last decade or so, which was unavailable in the FRBM-constrained regime. This fiscal boost has been central to the high growth rates of recent years.

This is a good case study for at least two reasons. One, while such quantitative targets do play a fiscal disciplining role, there’s nothing sacrosanct or objective about arbitrarily defined thresholds. In fact, a rigid adherence to such targets is counter-productive and growth-squeezing. Second, in a world where these targets have become accepted norms, market perceptions about reform commitment and fiscal prudence can significantly expand the fiscal space available for governments. Market credibility provides the flexibility for fiscal expansion.

So what does this all say? Here is the summary from ChatGPT

Over the last five decades, India’s growth experience shows no stable linear relationship between fiscal deficits and growth. Periods of high growth have occurred under both fiscal expansion and consolidation. Inflation control appears growth-enhancing primarily in high-inflation regimes, while capital formation is largely pro-cyclical. The results underscore that fiscal quality, institutional credibility, and macro stability matter more than headline fiscal aggregates.

A major macroeconomic challenge for India going forward will be the management of its fiscal balance. It must pursue fiscal consolidation to significantly reduce its current high flows and stock of debt, while also significantly raising GFCF. And it must do all these at a time when private investment remains caught in a low equilibrium trap with no signs of a breakout, and when global headwinds are likely to squeeze capital inflows and export growth. This is especially daunting since, as the figures show, economic growth since the GFC, and more so since the pandemic, has been largely propped up by public investment, which is now hitting hard fiscal constraints.