There’s a fundamental competition problem in markets where network effects (e.g., the platforms offered byAmazon, Google, and Meta) and/or technological path dependencies (e.g. Nvidia’s constantly evolving versions of ever more sophisticated GPUs) create rising entry barriers and confer ever-widening competitive advantage, and where accordingly companies are incentivised to deepen their moats and keep expanding their market shares.

As an illustration, the Dutch lithography behemoth, ASML, may have the deepest and broadest moat among firms in any industry.

Even in an industry with dominant or near-monopolistic firms - Nvidia in the design of chips that run AI applications, TSMC in the fabrication of processing chips, and Samsung and SK Hynix in high bandwidth memory (HBM) chips - ASML stands out. Consider the extent of its monopoly.

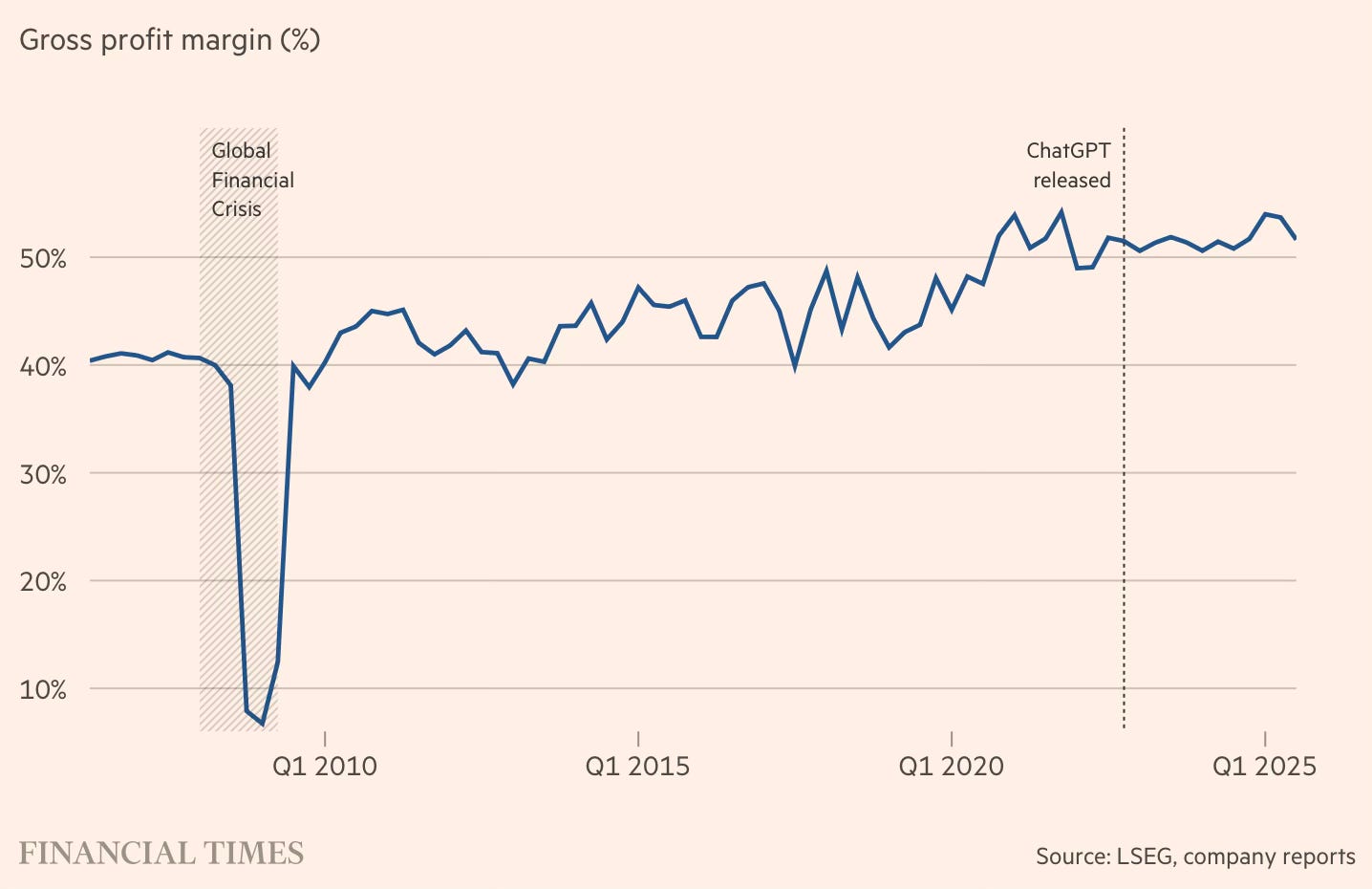

ASML sells just over 40 of its most advanced chipmaking machines each year. For over a decade, investors questioned whether such limited volumes could ever add up to a viable business. Those doubts have aged badly. After an 80 per cent rise in its share price over the past six months, ASML is now valued at more than $500bn... It is the only company that can make the extreme ultraviolet lithography machines required to produce those advanced chips. Each one has a starting price of $220mn and there is no commercially credible alternative supplier... In most industries, a monopoly this profitable — ASML’s gross profit margins were 52 per cent in the third quarter — would attract competition, especially from regions that already lead in related technologies.

What explains this monopoly?

The technology behind EUV machines is a chain of almost impossible steps, all of which have to work at the same time. Modern chips are made by printing patterns, layer by layer, on to silicon using light. To do this, engineers first need to create a form of light that does not occur naturally. Powerful lasers are fired at microscopic droplets of molten tin, turning them into plasma hotter than the surface of the Sun. That creates a pulse of extreme ultraviolet light, which is then reflected off a series of mirrors, each made with atomic-level precision and taking months to make, before the pattern is finally transferred to the silicon wafer. The hardest part to replicate is the optics. EUV-grade mirrors are produced by a single supplier: Carl Zeiss SMT. They are the product of decades of tightly integrated development between Zeiss and ASML.

Even if a peer could replicate that technology, the economics do not work. Any new entrant would sell too few machines each year to recover development costs, yet those machines would still be expected to deliver near-perfect reliability from day one. Chip fabrication plants operate continuously… As a result, chipmakers are unwilling to experiment with unproven EUV tools in volume production. That means a rival would never accumulate the field data required to improve.

ASML shipped its first EUV machine in 2006 and its first production capable system in 2013. Because chip factories run around the clock, cumulative operating hours now run into the millions. That gap in real world operating data explains why Nikon and Canon, once ASML’s peers in lithography, ultimately withdrew from pursuing EUV lithography systems over a decade before it became commercially viable, and why no successor has emerged since their exit… ASML shows how, beyond a certain technological threshold, markets no longer correct monopolies.

ASML may be the most egregious illustration of a pervasive market failure in deep technology markets, arising from innovation-induced moats.

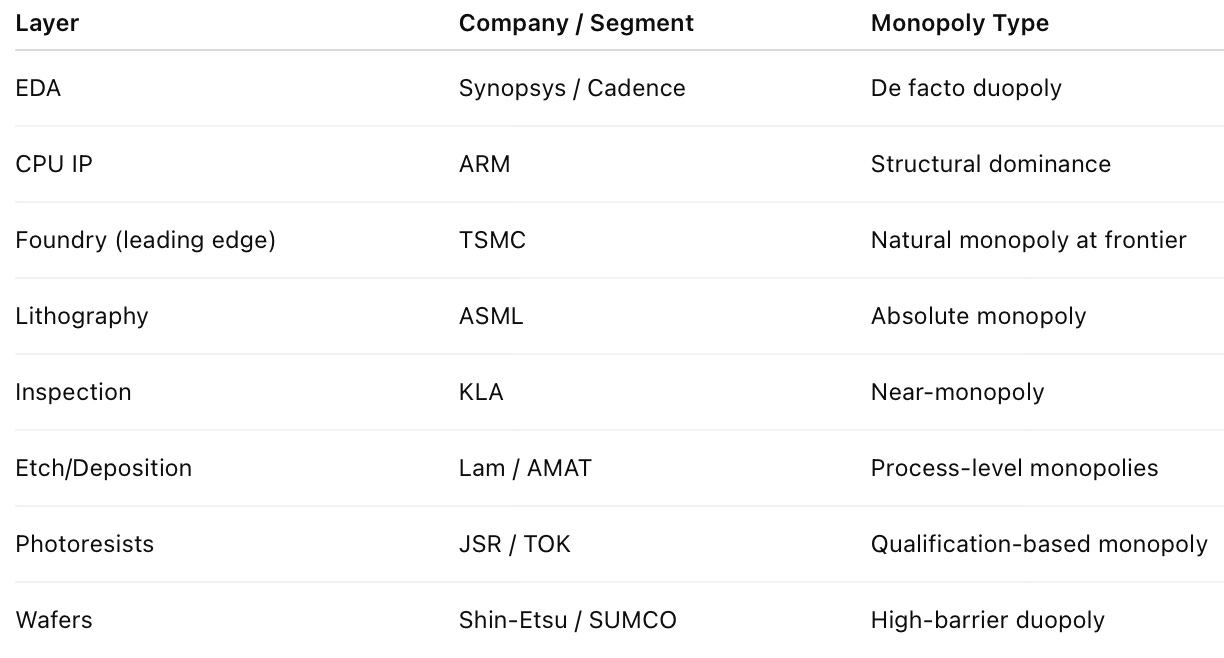

This moat is a result of the structural characteristics of the technology that creates a dynamic natural monopoly, arising from a combination of a long period of co-evolution with suppliers and customers, unmatchable accumulated R&D and tacit knowledge, high capital intensity and irreversibility (once invested, exit is costly and entry is irrational), and very long time horizons. In fact, the entire semiconductor chip design-to-fabrication value chain, including the equipment used, can be considered a stack of interlocking monopolies.

It is therefore unsurprising that this is the only major market where China has struggled to make a breakthrough. All the dominant firms are either US, European, or Japanese.

Such market failures are true across deep technology markets - commercial aircraft (Boeing/Airbus), jet engines (GE Aerospace, Rolls-Royce, Pratt & Whitney), electron microscope (Thermo Fisher Scientific, JEOL), industrial automation (Siemens, Rockwell Automation), etc.

Traditional anti-trust measures are unlikely to be effective in addressing market failures arising from the structural characteristics of the technologies involved. As the Chinese are finding out, even throwing massive amounts of money can do little to cross the moats.

In addition to the moats created by the structural characteristics of the technology itself in these deep tech products, the manufacturing of major components for these products is also protected by daunting entry barriers arising from the market structure.

Take semiconductor chip design, say, for a market for System on Chips (SoC) for various digital equipment (laptops, cameras, mobile phones, telecom equipment, etc.). This market is dominated by the likes of American (Qualcomm and Broadcom) and Taiwanese (Mediatek and Realtek) SoC designers. The OEMs in this market, themselves large multinational incumbents, are locked into close long-term partnerships with one or other of these companies.

Even if a new chip design startup assembles a solid team and does tapeouts of an SoC that can be readily deployed in a device, it would still need an OEM to deploy the same. However, the OEM, which has a well-established supply chain, would have limited incentive to risk the experiment of trying out a brand-new supplier for any component, much less a critical one like the SoC. The OEM’s concerns are understandable given that it would require deep and mature institutional capabilities for the supplier to respond swiftly to rapidly evolving technologies and standards (for example, in telecommunications, a new 3GPP release happens every 6-12 months) and the resultant demands of the OEM.

This is a problem not just to SoC but to any chip, or any other sophisticated electronic component, where moats are high. The net result is that breaking into this market becomes almost impossible. Since component manufacturing is generally an essential requirement to catalyse product manufacturing, barriers to the former end up further entrenching incumbents in the latter.

It is relevant here that Chinese firms have made some headway in these markets. Their breakthroughs have come by riding on a wide base of domestic OEMs. In their quest to diversify away from the Western chip firms and lower their costs by leveraging their massive volumes (also from their ever-expanding export volumes), they had the incentive to bet long-term on domestic chip design firms. As a practice, starting with a small share of their overall requirement, they gradually increase the share of their sourcing from domestic chip firms. The massive subsidies and the strong push by the Chinese state to nurture indigenous firms have facilitated this process.

The chip design firms, too, have generally started with a less sophisticated version of chips, developed capabilities and moved up the value chain into more sophisticated versions.

As an example, by privileging a Chinese 3G standard, Beijing forced carriers and vendors to adopt equipment and handsets that supported it — creating immediate, captive volume for domestic baseband suppliers. That is a strong example where a regulatory mandate (a standard) directly created market share for local firms.

So what can be done to lower the moats and enable entry in some of these markets?

In these markets, where moats are so deep and wide, industrial policy actions by way of financial incentives (subsidies) to lower entry barriers may struggle. How much incentive is adequate to bridge the disability faced by domestic chip firms? How will it help open up the platforms of OEMs to the new chip design firms? There are hard limits to how much support can be given by fiscally constrained governments.

Therefore, in some of these markets, notwithstanding their distortionary risks, hard constraints by way of mandates may be required to break the entrenched market equilibrium of dominant foreign OEMs and their suppliers. These mandates can take the form of domestic content rules, public procurement preferences, and standards.

These mandates must be carefully designed and implemented to minimise market distortions and inefficiencies. It may be advisable to start the domestic mandate with a small percentage of sourcing, and that too in components where local capability is plausible, and by allowing tradeable compliance credits (firms unable to source locally can buy credits that fund supplier development). There should also be sufficient safeguards in terms of waivers and emergency provisions that allow temporary exceptions. Most importantly, the mandates should be administered transparently and closely monitored to make course corrections if required.

For sure, these mandates can only create some initial market access and cannot work on their own. They must be complemented with industrial policy incentives, patient risk capital, supply-chain development, and commercial incentives for OEMs. And even with all these, it can be effective in facilitating entry only to a few deep tech market segments.

No comments:

Post a Comment