Manufacturing has undergone transformational shifts in the last three decades. Technological advances, liberalisation of global trade, the practice of outsourcing manufacturing activities and offshoring them, and the emergence of China as the overwhelmingly dominant offshoring destination, have brought forth a quarter century or more of remarkable economic stability and prosperity. But this has also obscured severe economic damage and serious national security vulnerabilities that are now very evident and are convulsing domestic politics across countries.

These trends have triggered debates on the future of manufacturing. On the one hand, some argue that reshoring manufacturing activities and reviving manufacturing jobs is a futile pursuit, and countries should instead focus on their services sector jobs. On the other hand, others, notably in the US, favour restoring manufacturing to its old glory. While the former tend to think that outsourcing and offshoring were largely a free lunch and there’s something irreversible about it, the latter see the revival of manufacturing jobs in terms of raising tariffs and making everything domestically. This post will seek to put the ideological debate in its perspective.

The Economist has a very good fact-filled article which argues that pursuing manufacturing jobs may be futile and inefficient. It shows that the US manufacturing economy remains formidable, traditional manufacturing jobs pay less than others, and thanks to automation and other factors, even if there is a reshoring, the old jobs are unlikely to return.

Manufacturing produces more than in the past with fewer hands—a transformation much like that undergone by agriculture. Accessible, middle-class work of the sort that once drew crowds to the factory gates in America’s Fordist heyday has all but vanished. According to our analysis, the most similar work to the manufacturing jobs of the 1970s is not to be found in factories, which are now automated and capital-intensive, but in employment as an electrician, mechanic or police officer. All offer decent wages to those lacking a degree.

Whereas almost a quarter of American workers were employed in manufacturing in the 1970s, today less than one in ten is. Moreover, half of “manufacturing” jobs are in support roles such as human relations and marketing, or professional ones such as design and engineering. Less than 4% of American workers actually toil on a factory floor. America is not unique. Even Germany, Japan and South Korea, which run large trade surpluses in manufactured goods, have seen steady declines in the share of such employment. China shed over 20m factory jobs from 2013 to 2023—more than the entire American manufacturing workforce. Research from the imf calls this trend “the natural outcome of successful economic development”.

As countries grow richer, automation raises output per worker, consumption shifts from goods to services, and labour-intensive production moves abroad. But this does not mean factory output collapses. In real terms, America’s is over twice as high as in the early 1980s; the country churns out more goods than Japan, Germany and South Korea combined. As the Cato Institute, a think-tank, points out, America’s factories would, on their own, rank as the world’s eighth-largest economy.

Even a heroic reshoring effort eliminating America’s $1.2trn goods-trade deficit would do little for jobs. In the production of that amount of goods, about $630bn of value-added would come from manufacturing (with the rest from raw materials, transport and so on). Robert Lawrence of Harvard University estimates that, with each manufacturing worker generating $230,000 or so in value added, bringing back production to close the deficit would create around 3m jobs, half on the factory floor. That would lift the share of the workforce in manufacturing production by barely a percentage point. Assume this was done by levying an average effective tariff rate of 20% on America’s $3trn of imports, and it could cost an extra $600bn, or $200,000 per manufacturing job “saved”. That is a high price for jobs that are not as attractive as in the past…

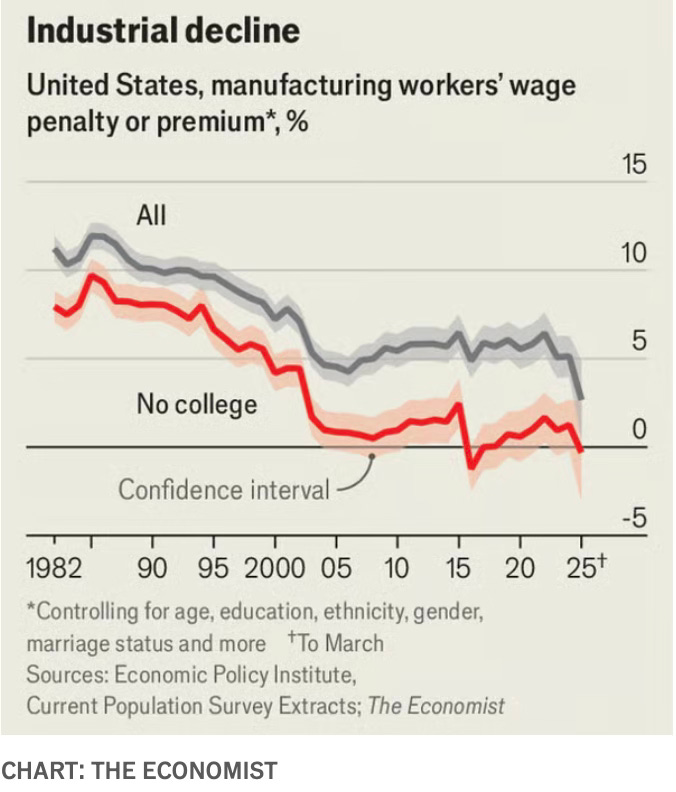

Today factory-floor work lags behind non-supervisory roles in services on hourly pay. Even if you control for age, gender, race and more, the manufacturing wage premium has collapsed. Using methods similar to the Department of Commerce and the Economic Policy Institute, we estimate by 2024 the premium had more than halved since the 1980s. For those without a college education, it has gone entirely, even though such workers still enjoy a premium in construction and transport. Productivity growth has fallen, too: output per industrial worker is now rising more slowly than per service-sector worker, suggesting wage growth will be weak as well…

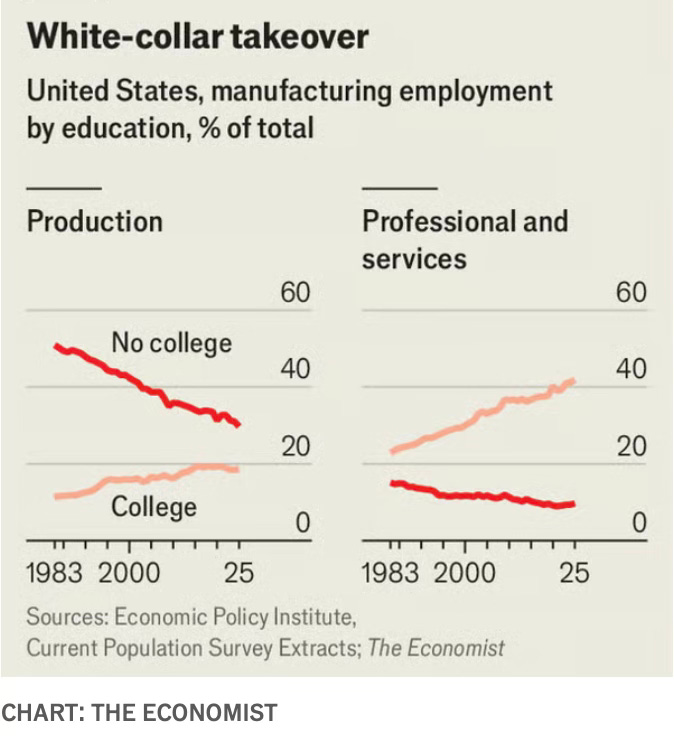

A job in industry is also now harder to attain. Modern factories are high-tech, run by engineers and technicians. In the early 1980s blue-collar assemblers, machine operators and repair workers made up more than half of the manufacturing workforce. Today they account for less than a third. White-collar professionals outnumber blue-collar factory-floor workers by a wide margin. Even once obtained, a factory job is far less likely to be unionised than in previous decades, with membership having fallen from one in four workers in the 1980s to less than one in ten today.

What are the modern equivalents of factory workers?

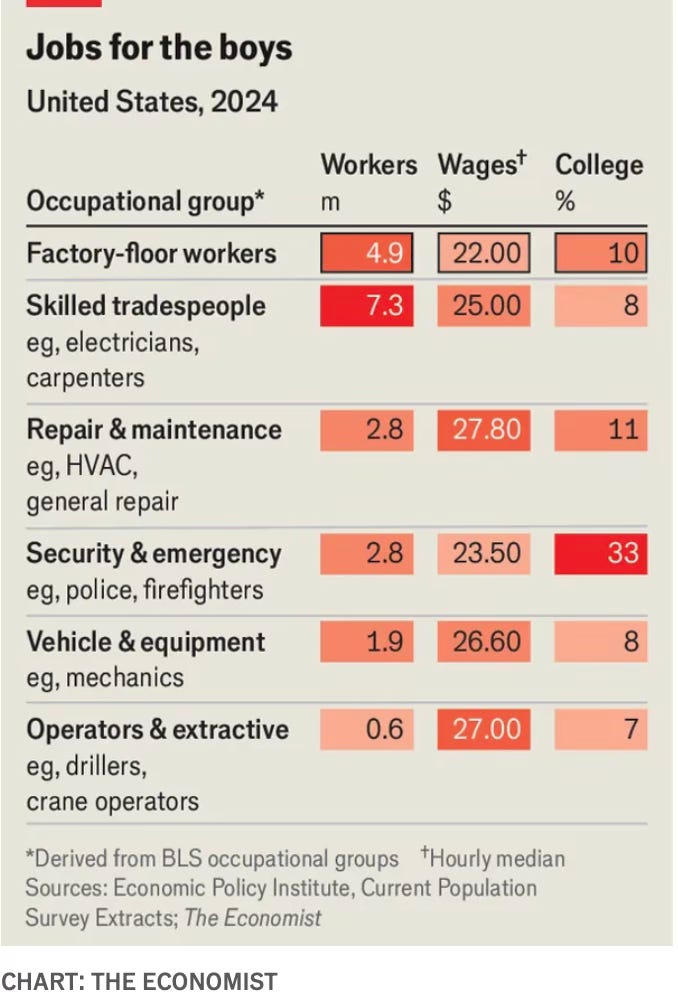

What offers decent pay, unionisation, requires no degree and can soak up the male workforce? The result: mechanics, repair technicians, security workers and the skilled trades. Over 7m Americans work as carpenters, electricians, solar-panel installers and in other such trades; almost all are male and lack a degree. The median wage is a solid $25 an hour, unionisation is above average and demand is expected to rise as America upgrades its infrastructure. Another 5m toil as repair and maintenance workers—think HVAC technicians and telecom installers—and mechanics, earning wages well above the factory-floor average. Emergency and security workers also show similarities; over a third are union members.

Still, these jobs differ from manufacturing in one important way: there is no such thing as an hvac company town. Factories once powered whole cities, creating demand for suppliers, logistics and dive bars. The new jobs are more dispersed and, as such, less likely to prop up local economies. Yet although the benefits are more diffuse, they are almost as large. Nearly as many people are employed in such categories as held manufacturing jobs in the 1990s. With better wages, less credentialism and stronger unions, they may look more attractive than modern factory jobs to working-class Americans… Skilled trades and repair workers should see growth of 5% over the next decade, according to official projections; the number of manufacturing jobs is expected to fall. The fastest-growing categories for workers without degrees are in health-care support and personal care, which are expected to grow by 15% and 6%, respectively. These include roles such as nursing assistants and child-care workers, and do not look anything like old manufacturing jobs owing to their low pay.

There’s no disputing the point being made here that it’s a futile pursuit to restore the old manufacturing status in terms of jobs. However, that does not detract from the importance of focusing on manufacturing, especially in specific sectors for economic and strategic reasons. Further, given the circumstances involving China, any attempt to reshore manufacturing requires industrial policy and must be supplemented with protectionist barriers. Finally, no one country can match China's manufacturing dominance, and the only way out is to build within a coalition of allies a broad manufacturing base at a scale that can compete with China. None of these is mutually exclusive.

Manufacturing is critical for several reasons. Historically, industries such as textiles, footwear, steel, cement, electricity generation, heavy equipment, consumer durables, electronic devices, and automobiles have been the mainstays of job creation and economic growth in both developed and developing countries. The economies of small towns to large regions have been built on these industries. They also tend to create 2-5 (or more) indirect jobs for every direct manufacturing job. An estimate by the Economic Policy Institute in the US shows that the number of indirect jobs lost for every 100 direct jobs lost is 744.1 for durable manufacturing compared to just 122.1 for retail trade. Services sector industries have far lower job multipliers.

Manufacturing is also unique when compared to other sectors insofar as its industries have spillovers that go beyond job creation. Making things requires more things, which are made elsewhere by others. It spawns ecosystems of suppliers and intermediaries. Manufacturing involves technologies and practices that generate learning spillovers, which enhance productivity. Most importantly, it creates the conditions for innovations and technological progress, which in turn further boost productivity. Finally, manufactured goods are tradeable and therefore subject to the competitive pressures of a world economy, thereby rewarding efficient producers and punishing laggards. As economists like Dani Rodrik and others have written, manufacturing creates multipliers and productivity improvements unlike any other sector.

Patrick McGee’s new book on Apple brilliantly illustrates how Apple transformed Foxconn by embedding its engineers and building capabilities, which in turn transformed Shenzhen by creating the foundations for an ecosystem of world-class manufacturing, which in turn transformed China itself into the factory of the world.

The journalist James Fallows, who lived in China in the late 2000s, has argued that Terry Gou ranks second only to Deng Xiaoping in transforming China into an industrial behemoth over the previous fifty years. This is an extraordinary claim, but one backed up even by Gou’s rivals. “The reason Shenzhen is Shenzhen is Terry Gou,” says a high-ranking contract manufacturing executive. “Without his ambition, Shenzhen wouldn’t be the manufacturing power it is.

The book also quotes Intel’s Andrew Grove lamenting the trend of outsourcing of manufacturing work by the US PC makers.

Andrew Grove would later diagnose the problem as “a general undervaluing of manufacturing - the idea that as long as ‘knowledge work’ stays in the US, it doesn’t matter what happens to factory jobs.” But as Grove warned: “our pursuit of our individual businesses, which often involves transferring manufacturing and a great deal of engineering out of the country, has hindered our ability to bring innovations to scale at home. Without scaling, we don’t just lose jobs - we lose our hold on new technologies. Losing the ability to scale will ultimately damage our capacity to innovate.”

Most importantly, and especially so given recent events involving China, there’s a strategic aspect to the reviving manufacturing imperative. The pandemic exposed countries to their extreme dependency on China for everything from face masks to active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) and formulations. Such concentrated health risks pose existential challenges, and it’s not in the national security interest that countries expose themselves to such vulnerabilities. Besides, in recent years, countries have come to realise their excessive dependence on China for all kinds of manufacturing, including entire interconnected industries like green technologies. This kind of dependence on one economy has not been seen even when the US was the dominant manufacturing economy.

This dependence becomes a serious national security threat when faced with rising geopolitical tensions and trade wars. In recent years, China has abandoned Deng Xiaoping’s policy of ‘hide your strength and bide your time’ to pursue an aggressive foreign policy and precipitated border conflicts with neighbours. It has shown that it’s not averse to weaponising its dominance in manufacturing to restrict trade with its perceived adversaries, most famously manifest in the country’s policy on the exports of rare earth minerals.

In December 2024, China announced a ban on the export of dual-use critical minerals like gallium, germanium, antimony, and superhard materials, which are used in the production of semiconductors and batteries as well as communications equipment components and military hardware such as armour-piercing ammunition. The country produces 98% of the global supply of gallium and 60% of germanium. In January 2025, it imposed restrictions on the export of technologies related to lithium extraction and the making of advanced battery materials.

Then, in response to the US reciprocal tariffs of April 2, the Chinese government imposed export restrictions on six heavy rare earth elements that are refined almost entirely in China and magnets made from them, of which 90% are made in China. Their exports are now licensed, and obtaining these licenses has become the point where leverage is being exercised. Further, reaffirming its intent, Beijing has also been cracking down on illegal trade.

More generally, it has also been creating hurdles to exports to certain countries. For example, India has been targeted selectively with several restrictions. Chinese authorities have been making it difficult for Foxconn, the Taiwanese contract manufacturer of Apple, to send machinery and Chinese technical managers to India to help build its supply chain. Customs delays and other obstacles are being raised to impede the flow of components and equipment.

For all these reasons, it’s a legitimate, even essential, requirement for productivity improvements, long-term economic growth, and, most importantly, national security for a country to have a deep and diverse manufacturing base. It’s important to acknowledge this requirement and view it separately from the ongoing debates and controversies about how to address the problem. The challenge should be about developing a strong manufacturing base (and not reviving some bygone labour share in manufacturing) in the least distortionary and inefficient manner.

Economists and experts who point to the beneficial effects of free trade tend to overlook the necessity of a domestic manufacturing base for both economic productivity and national security reasons. They harp on the benefits of free trade by looking at the last three decades. In this period, globalisation and the emergence of China helped expand global economic output at an unprecedented pace for a sustained period. It has enabled the biggest poverty reduction episode in history. Consumers have benefited from the globalised market and cheap Chinese imports, which kept inflation down for over three decades. The goldilocks of low inflation and high growth was achieved during this Great Moderation. In addition, China’s spectacular manufacturing capabilities have been central to the successes of the green transition, especially in the rapid scaling of renewable electricity generation technologies.

It’s therefore only natural that, when seen in isolation, experts see a resounding case for the continuation of the status quo. But they make the mistake of not stepping back and taking into account the unmatched benefits of manufacturing and its central importance for innovation, and the serious national security vulnerabilities that are surfacing amidst the growing geopolitical tensions between China and the US.

Finally, it’s a mistake to view the idea of restoring the manufacturing base as each country trying to bring back all manufacturing. Instead, the objective should be two-pronged. One, independent of the current geopolitical circumstances, all large economies should strive to have a strong manufacturing base, especially with capabilities across all strategically important sectors. This is important not only for economic reasons but also for strategic and security reasons, which are discussed earlier.

Two, instead of the futile pursuit of each country (read the USA) trying to develop domestic manufacturing capabilities to match China, the objective should be to create the full suite of manufacturing capabilities within a broad coalition of like-minded countries. There are serious limitations to acting alone, and therefore, the necessity to mobilise a coalition of like-minded partners. No one country, even one as powerful and economically dynamic as the US, can break the stranglehold of China’s manufacturing dominance. The only realistic strategy to counter China’s dominance is to develop manufacturing capabilities across major industries within the coalition.

Kurt Campbell and Rush Doshi (also this) have argued in favour of America forging alliances with like-minded partners to create a meta-economy that can outcompete China and manufacture at scale.

To achieve scale, Washington must transform its alliance architecture from a collection of managed relationships to a platform for integrated and pooled capacity building across the military, economic, and technological domains. In practical terms, that might mean Japan and Korea help build American ships and Taiwan builds American semiconductor plants while the United States shares its best military technology with allies, and all come together to pool their markets behind a shared tariff or regulatory wall erected against China. This kind of coherent and interoperable bloc, with the United States at its core, would generate aggregate advantages that China cannot match alone...

For Washington, three realities must be central to any serious strategy for long-term competition. First, scale is essential. Second, China’s scale is unlike anything the United States has ever faced, and Beijing’s challenges will not fundamentally change that on any relevant timeline. And third, a new approach to alliances is the only viable way the United States can build sufficient scale of its own. Altogether, this means that Washington needs its allies and partners in ways that it did not in the past. They are not tripwires, distant protectorates, vassals, or markers of status, but providers of capacity needed to achieve great-power scale. For the first time since the end of World War II, the United States’ alliances are not about projecting power, but about preserving it.

During the Cold War, the United States and its allies outclassed the Soviet Union. Today, a slightly expanded configuration would handily outclass China. Together, Australia, Canada, India, Japan, Korea, Mexico, New Zealand, the United States, and the European Union have a combined economy of $60 trillion to China’s $18 trillion, an amount more than three times as large as China’s at market exchange rates and still more than twice as large adjusting for purchasing power. It would account for roughly half of all global manufacturing (to China’s roughly one-third) and for far more active patents and top-cited journal articles than China does. It would account for $1.5 trillion in annual defense spending, roughly twice China’s. And it would displace China as the top trading partner of almost all states. (China is today the top trading partner of 120 states.) In raw terms, this alignment of democracies and market economies outscales China across nearly every dimension. Yet unless its power is coordinated, its advantages will remain largely theoretical. Accordingly, unlocking the potential of this coalition should be the central task of American statecraft in this century.

But unfortunately, the Trump administration’s policies are pulling in exactly the opposite direction in terms of antagonising and decoupling from its traditional alliances.

Any effort to revive manufacturing will be costly. Consumers, businesses, and taxpayers must bear those costs. These costs are an internalisation of the costs of the negative externalities imposed by the practice of outsourcing and offshoring to China. I’ll blog separately on this.

No comments:

Post a Comment