Very few industries have generated as much discussion as the rare earth minerals and their extraction, processing, and refining. This post will consolidate the debate and offer some observations.

In response to the US reciprocal tariffs of April 2, the Chinese government imposed export restrictions on six heavy rare earth elements that are refined almost entirely in China and magnets made from them, of which 90% are made in China. Their exports are now licensed, and obtaining these licenses has become the point where leverage is being exercised. Further, reaffirming its intent, Beijing has also been cracking down on illegal trade.

Rare earth metals are used for making permanent magnets for electric vehicles, wind turbine motors, factory robots, drones, spacecraft, etc.; catalytic converters for cars; in defence technologies like laser guidance systems, radars, sonars, etc. Heavy rare earths are essential for making magnets that can resist the high temperatures and electrical fields found in cars, semiconductors and many other technologies. The NYT writes

The so-called heavy rare earth metals covered by the export suspension are used in magnets essential for many kinds of electric motors. These motors are crucial components of electric cars, drones, robots, missiles and spacecraft. Gasoline-powered cars also use electric motors with rare earth magnets for critical tasks like steering. The metals also go into the chemicals for manufacturing jet engines, lasers, car headlights and certain spark plugs. And these rare metals are vital ingredients in capacitors, which are electrical components of the computer chips that power artificial intelligence servers and smartphones… Carmakers need the magnets for the electric motors that run brakes, steering and fuel injectors. The motors in a single luxury car seat, for example, use as many as 12 magnets.

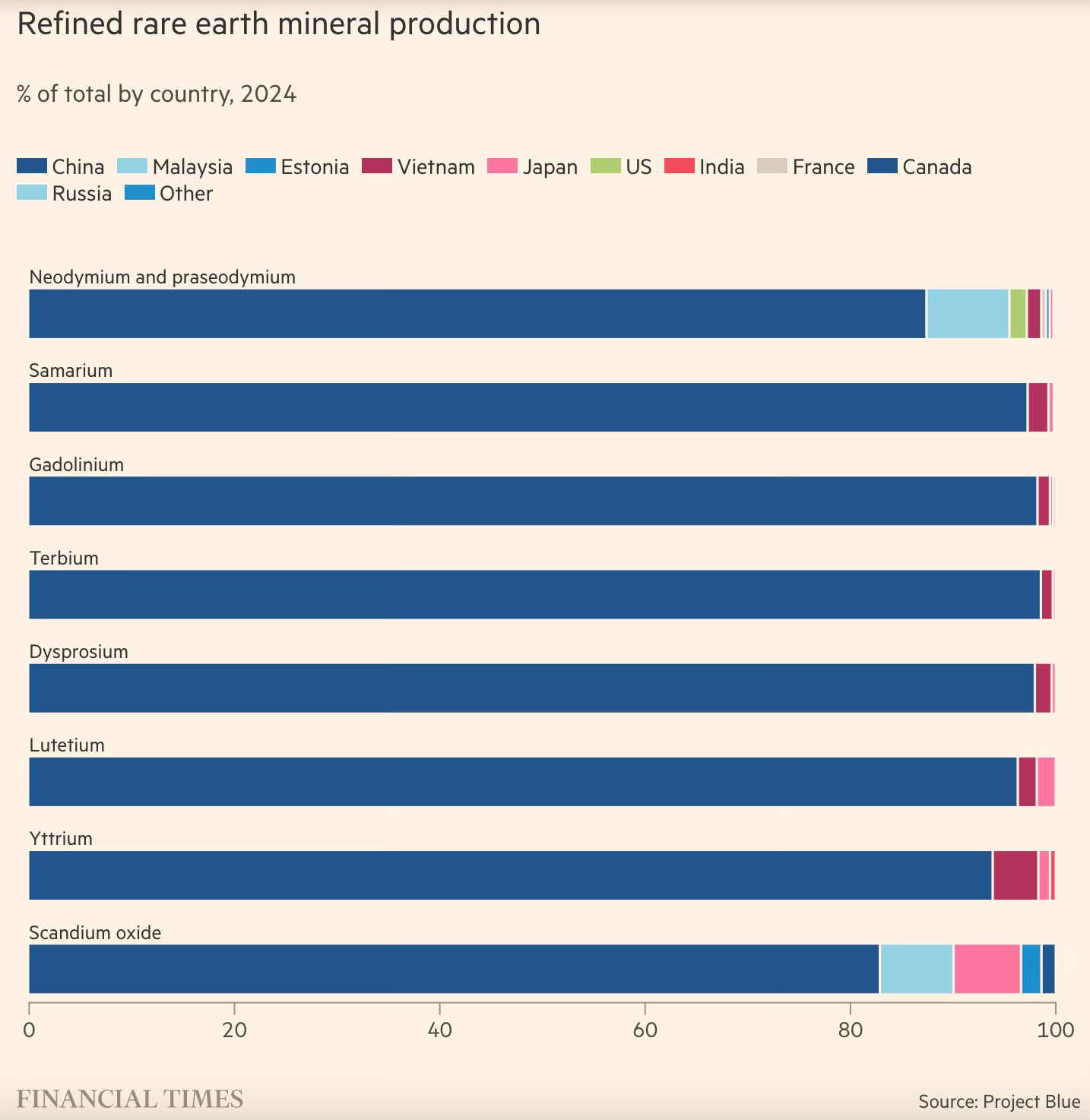

China’s control over these metals is near complete

Until 2023, China produced 99 percent of the world’s supply of heavy rare earth metals, with a trickle of production coming out of a refinery in Vietnam. But that refinery has been closed for the past year because of a tax dispute, leaving China with a monopoly. China also produces 90 percent of the world’s nearly 200,000 tons a year of rare earth magnets, which are far more powerful than conventional iron magnets. Japan produces most of the rest and Germany produces a tiny quantity as well, but they depend on China for the raw materials.

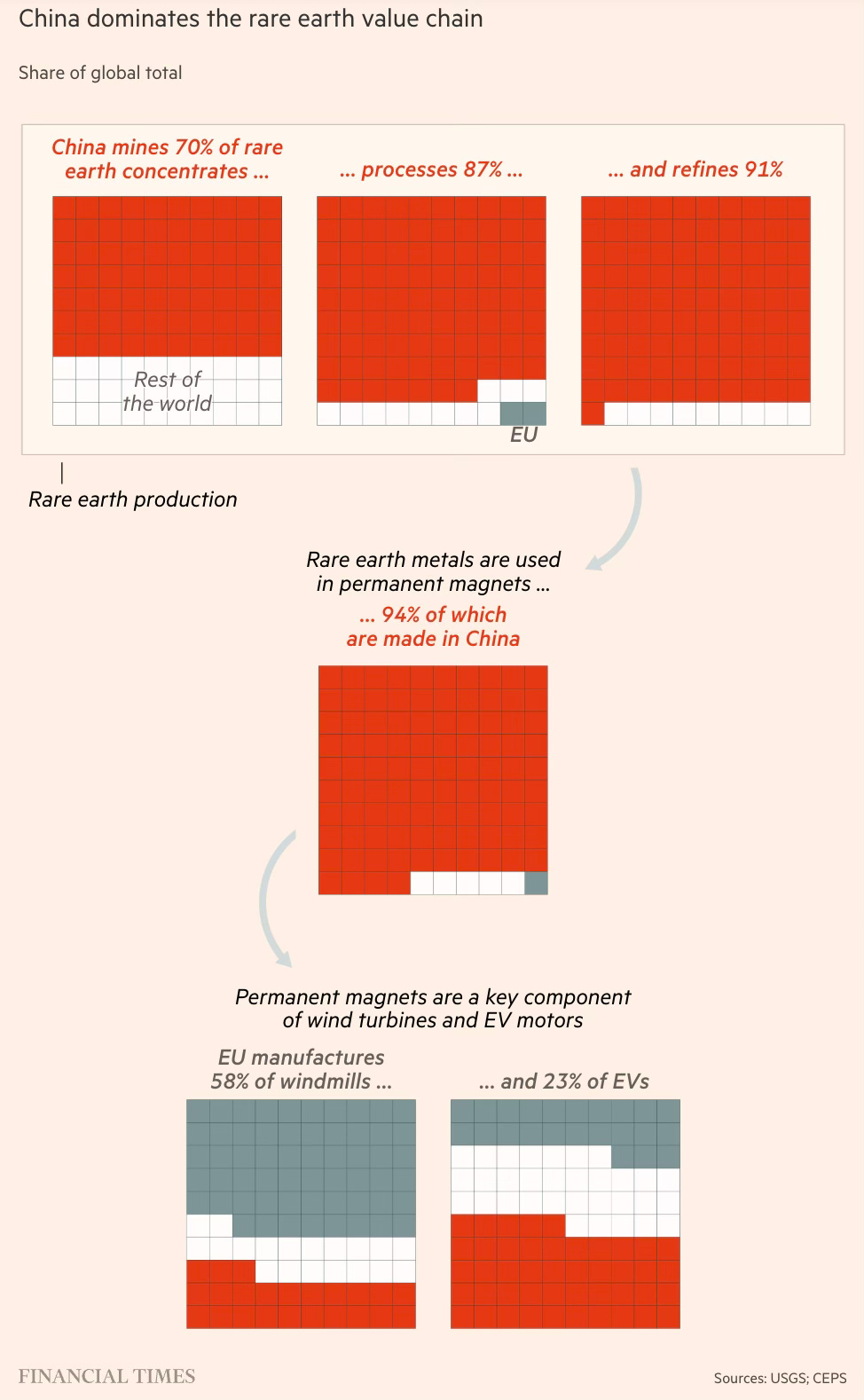

The graphic below illustrates its dominance of the rare earth value chain.

And rare earth minerals refining.

The restrictions on rare earth elements must be seen as a brilliant move by the Chinese.

Rare earth magnets make up a tiny share of China’s overall exports to the United States and elsewhere. So halting shipments causes minimal economic pain in China while holding the potential for big effects in the United States and elsewhere.

The US produces practically no rare earth metal, though successive governments in recent years have tried to restart the industry. But there are daunting challenges.

The sole American rare earths mine, located in Mountain Pass, Calif., stopped producing in 1998 after traces of heavy metals and faintly radioactive material leaked from a desert pipeline. Chinese state-controlled companies tried three times without success to buy the defunct mine before it was acquired by American investors in 2008. A $1 billion Pentagon-backed investment program followed in 2010 to improve environmental compliance and expand the mine and its adjacent refinery. But the costly complex was unable to compete when it briefly reopened in 2014, and closed again the next year.

MP Materials, a Chicago investor group that included a minority partner company partly owned by the Chinese government, bought the mine in 2017. The mine reopened the next year, but shipped its ore to China for the difficult task of separating the various kinds of rare earths. Only in recent months has the mine become able to chemically separate the rare earths in more than half its output. But this loses money because processing in China is so inexpensive. MP Materials built the new factory in Texas that will turn separated rare earths into magnets.

A considerable bottleneck lies in transforming separated rare earths into chemically pure metal ingots that can be fed into the furnaces of magnet-making machines. A New England start-up, Phoenix Tailings, is addressing that shortcoming, but its small scale underlines the challenge. Phoenix Tailings has taken over much of the staff and equipment of Infinium, a start-up that had tried to do the same thing. Infinium ran out of money in 2020, when American policymakers were more focused on the Covid-19 pandemic than rare earths. With Chinese rare earth minerals hard to get, Phoenix makes the metal from mine tailings: leftover material at mines that has already been processed once to remove another material, like iron.

Phoenix Tailings has four machines each the size of a small cottage at its factory in Burlington, Mass. Each one produces a 6.6-pound ingot every three hours around the clock. The operation’s overall capacity is 40 tons a year, said Nick Myers, Phoenix’s chief executive. He declined to identify the buyer but said it was an automotive company. Phoenix is installing equipment at a larger site in Exeter, N.H., to produce metal at a rate of 200 tons a year — still tiny compared with Chinese factories that produce more than that in a month.

There is an important reason why these efforts have struggled and largely failed to make much headway.

But little has happened because of a gritty reality: Making rare earth magnets requires considerable investments at every stage of production. Yet the sales and profits are tiny. Worldwide sales of mined rare earths total only $5 billion a year. That is minuscule compared with $300 billion industries like copper mining or iron ore mining. China has a formidable competitive advantage. The state-owned industry has few environmental compliance costs for its mines and an almost unlimited government budget for building huge processing refineries and magnet factories. Processing rare earths is technically demanding, but China has developed new processes. Rare earth chemistry programs are offered in 39 universities across the country, while the United States has no similar programs.

In a clear demonstration of their intent, Beijing has been cracking down on illegal exports of rare earth metals.

China’s Ministry of Commerce now requires Chinese producers to submit elaborate documentation for each request to export restricted rare earths or magnets. To prevent resales, the application requires Chinese companies to certify not just who is buying the material but how it will be used in subsequent steps of production, sometimes including photos of products, three rare earth industry leaders outside China said. These documents may provide Beijing with a detailed map of how rare earths are used abroad, and could make it easier for China to target specific companies and countries in the future…

Before the Covid-19 pandemic, smugglers routinely moved large quantities of rare earths across the border with Vietnam. A tiny refinery in northern Vietnam was the only facility outside China that could undertake the complicated steps needed to chemically process so-called heavy rare earths. But China built an elaborate system of fences with motion detectors along its southern border during the pandemic, after a series of incidents in which infected people entered China. The fences have since proved an obstacle for smugglers. The small refinery in Vietnam closed more than a year ago because of a dispute with the country’s tax authorities.

Beijing has also not missed the opportunity to further increase dependence on Chinese manufacturers.

Worrying still is a fresh insistence from Beijing that instead of sourcing magnets separately, carmakers buy entire electric motor assemblies from Chinese companies, or simply wait for the Chinese authorities to issue export permits to local rare earth magnet producers, as has been done, according to Reuters, for at least four magnet producers that include suppliers to Volkswagen… The problem with sourcing entire motors, as against just the magnets in them, is that carmakers would have to redesign their cars to accommodate the entire motor assembly, which comes in standard sizes. The ability to import magnets meant that manufacturers could calibrate the motor sizes to the design of their vehicles.

Some observations:

1. The near-complete dependence on China for rare earth elements was well known for years. Besides, given the restrictions imposed by China on exports to Japan in 2010 following a territorial dispute, there was always the strong likelihood, near certainty that China would weaponise its dominance if a need arose. In fact, at various times since Trump 1.0 initiated the trade war with China, it has dropped hints of its intent to use rare earth exports as a bargaining chip. There’s therefore nothing surprising about the Chinese decision on April 4.

2. Given the above, I’m surprised that the American auto makers and other users have not built up sufficient inventories of rare earths. It does not say much good about the risk mitigation strategies of these big multinational corporations if they are struggling just one month after China announced its export ban.

3. The shortage is also a manifestation of the problems with the model of American capitalism that not only elevates efficiency (and profits) maximisation above all else but marginalises resilience, fairness, and other considerations. A just-in-time inventory management approach is the exact opposite of resilient inventory management.

4. The squeeze being felt by Western companies due to the Chinese export restrictions on rare earths is also an example of how the Chinese appear to have used their limited leverage to maximise pain. In contrast, the US appears unable to squeeze China as much despite its control over high-technology equipment used in semiconductor chip manufacturing, aeroplanes, and defence technologies.

After all, the other side to the Western dependence on Chinese exports is the Chinese dependence on sales to Western markets to sustain jobs. While we hear so much about the former, there’s little that’s heard about the latter. Or is it likely that the effects on the Chinese firms and economy will start getting felt in the coming days? I am inclined.

5. Unlike the Americans, especially but not only under the Trump administration, as the comprehensive mechanism put in place to track exports from sales to end-use demonstrates, the Chinese have thought through their export restrictions.

Similar tracking mechanisms are now emerging in sectors like parts of the semiconductor manufacturing value chain. The US also face the challenge of coordinating with its allies who also make these critical equipment and technologies. In any case, as the Cold War between the US and China intensifies, such tracking mechanisms for critical materials and technologies are likely to become commonplace.

6. US firms seeking to refine rare earth minerals and manufacture magnets must overcome a formidable combination of challenges - the small size of the global market that would deter large firms from investing, the moat created by the nearly two decades’ head start and dominance enjoyed by Chinese firms, the catch up necessitated by the absence of domestic expertise and the need to start afresh, the daunting challenge of acquiring expertise in refining technology, and the significant environmental externalities imposed by rare earth refining. In addition, any new entrant will face a massive price competitiveness gap.

Therefore, this endeavour requires not only a very active industrial policy with large and long-drawn support, but also possibly direct engagement by the government. It appears that either the government should get one or two of the large mining companies to make a large investment, or a government-owned entity must enter the market. And these, in turn, highest level political resolve and capability to act.

7. Even with supply-side industrial policy and direct government role in refining and manufacturing, given the price competitiveness gap, domestic market uptake will be limited unless it’s complemented with demand-side initiatives. Besides, investors will hold back in committing money to any investments.

While tariffs are one way to bridge the gap (when the Chinese supply becomes available), it would require steep tariffs, given the size of the gap. Another response would be for governments to actively coordinate with the large users and have them commit to long-term purchases from domestic refiners and manufacturers. This form of industrial policy may need to be employed more effectively to counter the specific Chinese threat of cheap exports.

Given the ever-present geopolitical risks, if buyers of rare earth metals were rational, they would have diversified their sourcing of rare earth elements, even if it meant paying higher prices. But the market failure necessitates government intervention to nudge buyers of rare earth metals to pay the higher prices required to sustain a resilient supply chain for these critical minerals.

This is one more example of how the complex interplay of real-world factors invariably ends up distorting the markets and making government intervention necessary.

No comments:

Post a Comment