I blogged here on how narratives create a dissonance between perception and reality. I had also written that centrist parties, especially those that try to achieve the balance between capital and labour, struggle to retain any ideological mooring and end up alienating their core support base.

The Labour Party in the UK under Sir Keir Starmer may turn out to be a good example of this. As John Burn-Murdoch has shown brilliantly with data, the Labour victory is built on very shaky foundations. It received half a million fewer votes than its wipeout in 2019, just 34% of the votes, more than doubled its seat share!

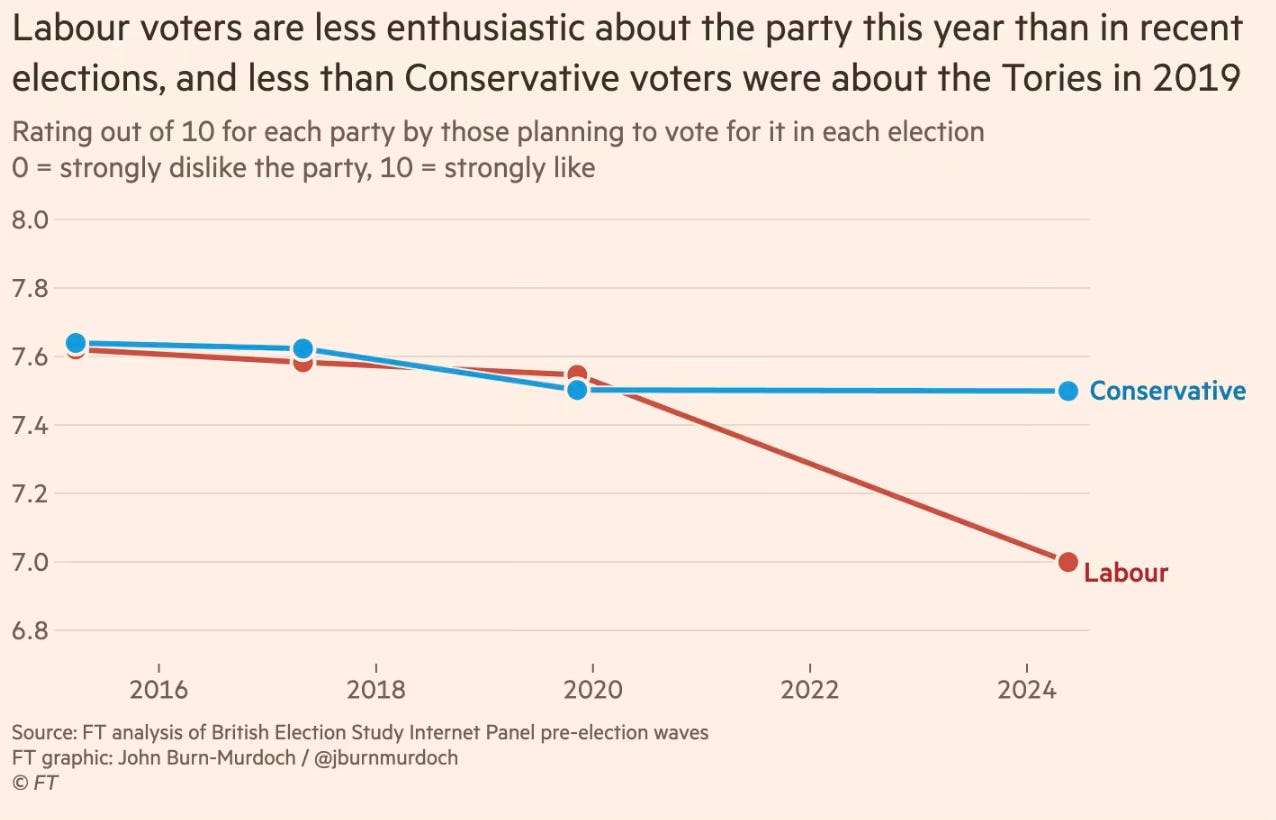

Despite their party bagging its second-highest seat tally in history, the lack of enthusiasm among Labour voters is striking.

Consider this about how Starmer reshaped Labour after Jeremy Corbyn’s extremism alienated voters.

Starmer, who won the Labour leadership on a leftwing manifesto offering tax rises and the nationalisation of key industries, now struck different themes. Attempting to win back core working class, social conservatives who had deserted the party during the Brexit years — and middle Britain’s moderate voters — he pulled the party back to a left of centre position. Corbynites were purged, antisemitism was ruthlessly stamped out, the party machine was retooled… During the long months running up to the snap election, Starmer rarely appeared in interviews without the union jack in the background, he adopted tougher language on migration and crime and… he put fiscal discipline and a pro-business agenda at the heart of Labour’s pitch… Starmer, whose previous costly promises to scrap university tuition fees or to bring private companies back under state control were ditched, “fully bought in” to the need for an iron grip on tax and spend policies… Starmer’s transformation of Labour from a leftwing protest party to a centrist government-in-waiting prompted claims that either he does not believe in anything, or that he is a closet leftwinger waiting to unleash a concealed socialist agenda on Britain.

… unlike many members of his incoming cabinet, Starmer is not a career politician. Instead he became a successful human rights lawyer and ended up in charge of the Crown Prosecution Service. He did not enter parliament until his fifties… his time running a big public service made him interested in making bureaucratic machines work. “He’s interested in how, not just what,” says one close ally, arguing that Starmer took a keen interest in turning Labour into an organisation that could deliver change in government. “He’s very professional,” McFadden says. “He likes things to be done right. He expects people to show up with their homework done. He chairs meetings well. He makes sure people know what has been agreed.”.. Sunak has also been among those who claim that Starmer stands for nothing, that he “flip flops” from one position to another; that he was a leftwinger while standing for his party’s leadership, where now he is posing as a fiscal ironman. In essence, the country has no idea what it is getting.

In keeping with centrism, Labour’s manifesto offered very little by way of meaningful reform.

For all the talk of change, Labour’s manifesto was one of the thinnest and centrist in its history. It had little new to say about such core issues as education and skills, public service reform and local government financing. It was largely silent about how both tax rises and austerity could be avoided without breaching its fiscal rules.

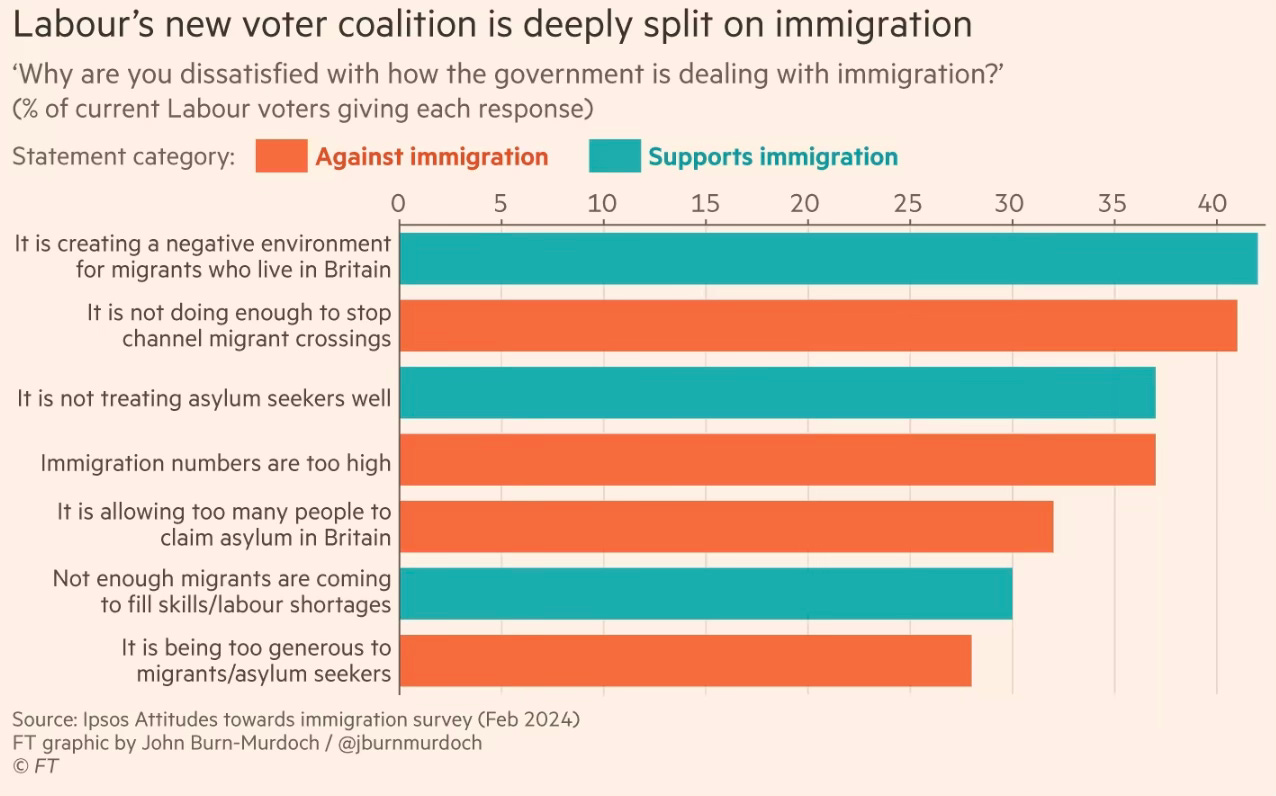

The contradictions in such non-ideological pragmatism is best exemplified in the Labour Party’s views on immigration and asylum.

The clearest illustration of the tightrope Starmer will have to walk here is the way Labour supporters are split into diametrically opposed factions. About a third are angry that the Conservative government created a negative environment for migrants already in the country and want Britain to take in more immigrants. But another 40 per cent identify the problem as too much immigration and too many people allowed to claim asylum.

Almost any position Starmer takes will anger one of these groups. More than 100 Labour MPs now represent constituencies where the right, should the Conservatives and Reform UK unite or ally, would unseat them at the subsequent election. This means that the progressive voters’ side of the debate is likely to be the one that loses out. Nobody should be surprised if the very same split that we’ve seen on the right is mirrored on the left by the next election, with Labour voters peeling off to the Greens and independents.

The short story is this. Keir Starmer was smart enough to apply his technocratic skills and professionalism to opportunistically stitch together a coalition that relied on shifting Labour to the centre and appealing to pragmatism while benefiting from the disillusionment and divisions among the conservative voters. For how long will this balancing act survive?

The problem with such moderation, as I blogged earlier, is that it leaves the party vulnerable to being captured by the interest groups that prefer the status quo. Change of the kind required to reset the balance between labour and capital; arrest widening inequality; roll back the capture of rule-making institutions, especially by Big Finance and Big Tech; break the stranglehold of financial interests; improve the prospects for the next generation, etc., will invariably get pushed to the side. It’s hard to imagine Starmer’s Labour undertaking the kind of measures that would meaningfully upend the status quo in these areas. It’ll tinker at the margins. Expect no more. Disillusionment can quickly set in and the core base will get alienated. The inevitable backlash can threaten liberal democracy and capitalism.

Starmer’s technocratic professional background and limited experience as a politician, coupled with decisions like the handing over of economic management to an out-and-out technocrat like former Bank of England official Rachel Reeves, means that we can expect the Labour government to be one more experiment with technocracy to resolve what are essentially political decisions. Such experiments are unlikely to succeed.

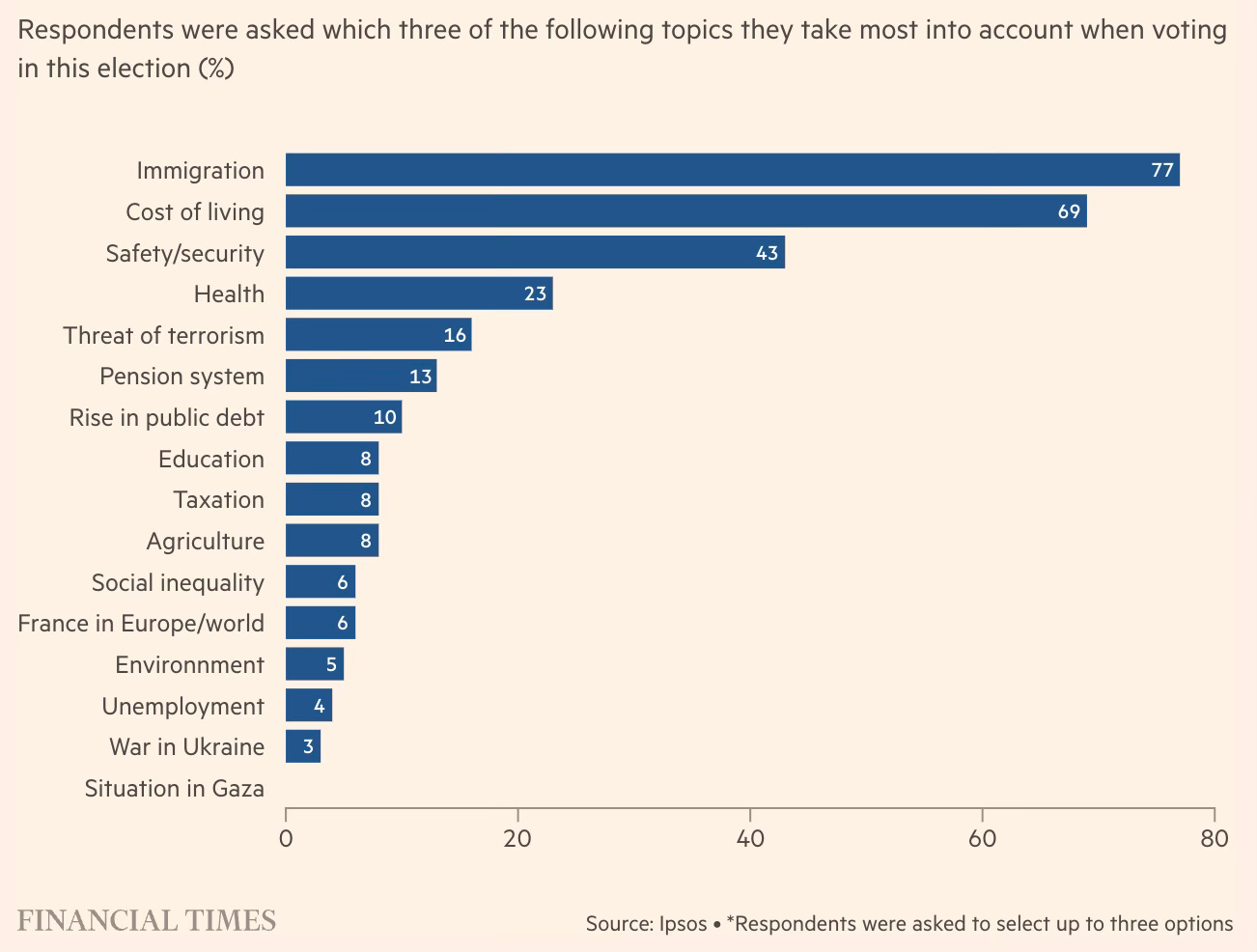

In this regard, Starmer and the Labour Party only need to look across the channel to France where similar centrism and technocracy by Emmanuel Macron and The Republicans have paved the path for the rise of the far-right populist Rassemblement National (RN) and Marine Le Pen. Esther Duflo writes,

Seven years of Macron but also five years of Socialist president François Hollande (under whom he was economy minister) have shown that whatever it is that the centrist politicians, always intent on demonstrating their reasonableness, keep on offering is now a losing proposition for most French voters. In 2022, it was largely the better off who voted for Macron and his party. The urban poor and the middle class mostly went for the left, and the rural poor and middle class for the RN. In 2024, the wealthier French started to peel off to the RN as well.

In this context, a recent article by the philosopher John Gray is instructive,

Rule by technocrats means bypassing politics by outsourcing key decisions to professional bodies that claim expert knowledge. Their superior sapience is often ideology clothed in pseudo-science they picked up at university a generation ago, and their recommendations a radical political programme disguised as pragmatic policymaking. Technocracy represents itself as delivering what everyone wants, but at bottom it is the imposition of values much of the population does not share… Populism is, among other things, the re-politicisation of issues the progressive consensus deems too important to be left to democratic choice. Immigration was one such issue, climate policy another. Both have stormed back into the political realm. The next will be the declining free market model to which all mainstream parties are committed…

Part of the reason Farage evokes such horror in polite society is that it has forgotten how traditional politicians used to behave… No one knows what Keir Starmer means by “mission-led government”, or remembers the five – or is it six– points of Sunak’s “clear plan”. More to the point, no one cares. Voters are turning to Farage because – like Thatcher, and Blair before he began rhapsodising on the wonders of AI – he tells a story that gels with what they feel about their lives… Farage is speaking to a section of the public – Brexiters who aim to punish the government for reneging on the promise to take control – that he is using to exact his own revenge on the Tories. Beyond this group, he is reaching many who are exhausted and angered by their daily battles to get by. The economic policies set out in Reform’s manifesto are unserious and undeliverable, but they connect with the inchoate sense of a hard-pressed multitude that the market-liberal regime is foundering…

In functioning democracies, technocracy rarely works for long. Relying on scraps of academic detritus, its practitioners struggle to keep up with events. Even when their theories are sound, they do not legitimate their policies… While the populist revolt is gathering momentum, Labour is going all in for technocratic management. Rachel Reeves proposes to give the Office for Budget Responsibility a greater role in approving fiscal policies.

The liberal parties that shift to the centre are especially vulnerable to such technocratic capture. To explain, let me use the framework illustrated by Jonathan Haidt with its six moral foundations - care, fairness, liberty, loyalty, authority, and sanctity. While the liberals are sensitive to the first three foundations, the conservatives are sensitive to all the six.

An illustration of this difference is this nice graphic that captures the priorities of the typical supporter of the French right-wing party, Rassemblement National (RN).

Note the low priority attached to typical concerns like inequality or the environment.

It can therefore be argued that voters with all six values will struggle to embrace a liberal party. Conservative voters will be put off by the narrow value base of liberal coalitions. Similarly, it’ll be difficult for people deeply sensitive to loyalty, respect for authority, and tradition and sanctity to be part of conservative coalitions. This is a blessing in disguise for conservative parties in so far as limits the scope for their ideological dilution.

In contrast, liberal parties are vulnerable to ideological dilution and capture. Unlike earlier eras, the moneyed interests of today do not owe their income and wealth to traditional sources. The beneficiaries of the managerial movement and shareholder capitalism (with its separation of ownership and management, and the power wielded by the executive class), and technological revolutions, are more likely liberals but with strong vested interests in maintaining the status quo. They are cohorts in the same schools, colleges, clubs, and residential colonies with intellectuals, ideologues, and opinion-makers in the academic, consulting, and journalistic worlds. This confluence tends to edge out the concerns of the working class from the priorities of the liberal parties and prioritise the preservation of the status quo.

Opportunistic pragmatism can mobilise convenient coalitions, but cannot be a substitute for ideological coherence. It’s hard to see Labour succeed in making any meaningful changes.

1 comment:

👍

Post a Comment