The problem of intermediating long-term capital to infrastructure has been a subject of intense debate and policy engagement. Most of the discussion is confined to creating the supply of insurance and pension fund capital and developing deep and liquid bond markets.

Instead, this post will examine how the existing supply and demand sides can be brought together in an institutional partnership to catalyse a new model for the flow of long-term capital to infrastructure sectors. It’ll do so in the context of pension funds.

This idea should be seen alongside others on infrastructure finance that I have blogged about. This post lists a few stylized facts about the infrastructure financing market and lays down a comprehensive infrastructure financing strategy for India. I blogged here that India could take the lead in demonstrating how DFIs can work on both the demand and supply sides to de-risk infrastructure projects and crowd in long-term capital respectively. I blogged here on how to reduce the cost of capital for foreign investments in the infrastructure sector, here on how to revise the credit rating framework in general, and here on de-risking and lowering the cost of capital of bank loans and de-risk the use of guarantees to crowd-in bank financing. All of these ideas are consolidated in this long paper.

Institutional investors like Pension Funds (PFs) can invest in infrastructure either directly (in infrastructure companies or specific project entities) or indirectly (through infrastructure funds). These investments can take the shape of listed and unlisted equity, or debt (subscribe to bonds issued by companies or projects), and can be in greenfield or brownfield projects.

The OECD’s annual reports that analyse the investments made by large pension funds (LPFs) and Public Pension Reserve Funds (PPRFs) provide several important insights. This and this are the reports for 2022 and 2023 respectively.

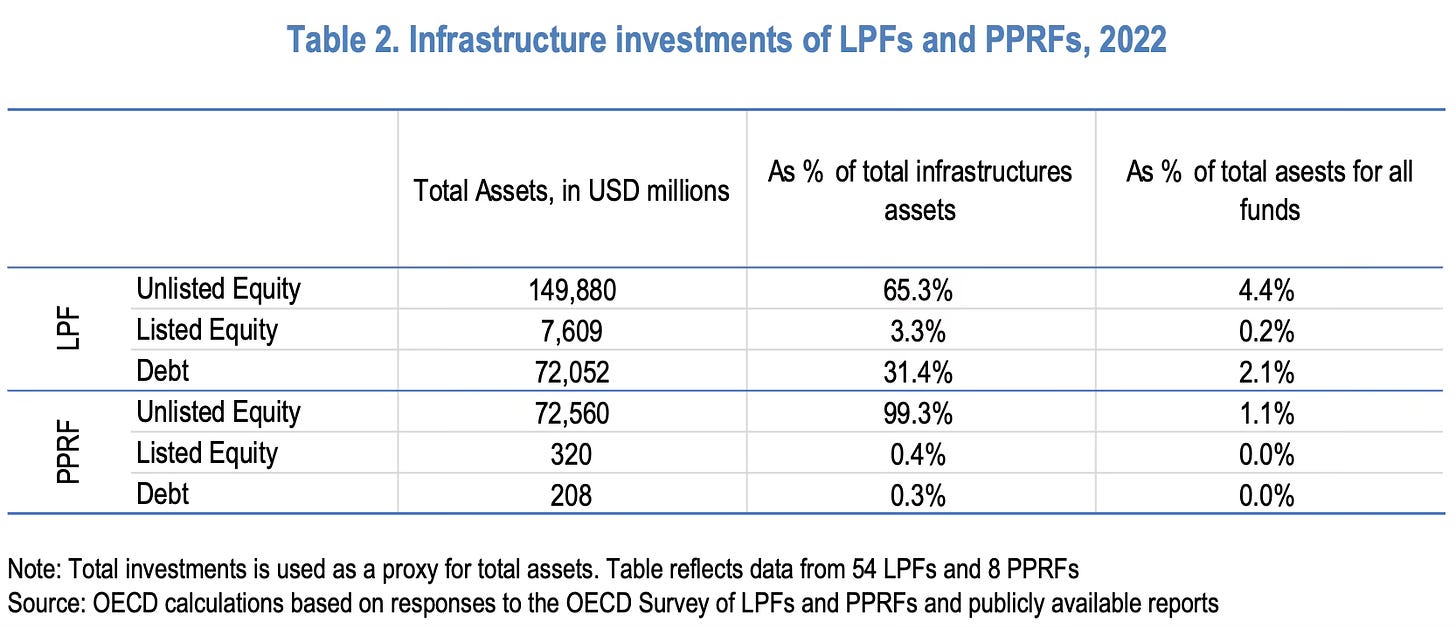

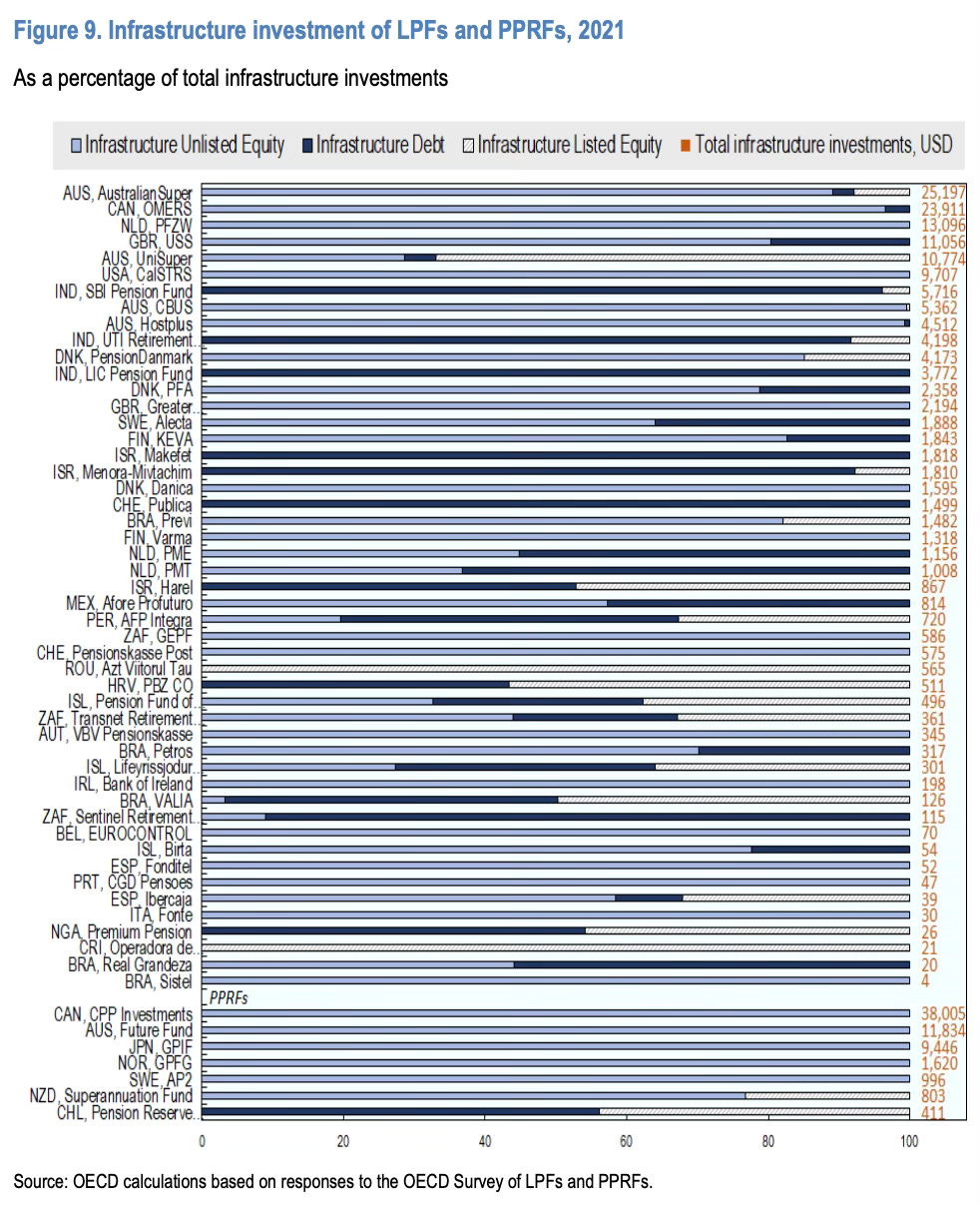

At the outset, it’s worth reminding that infrastructure forms around just 2-3% of the Assets Under Management (AUM) of pension funds globally.

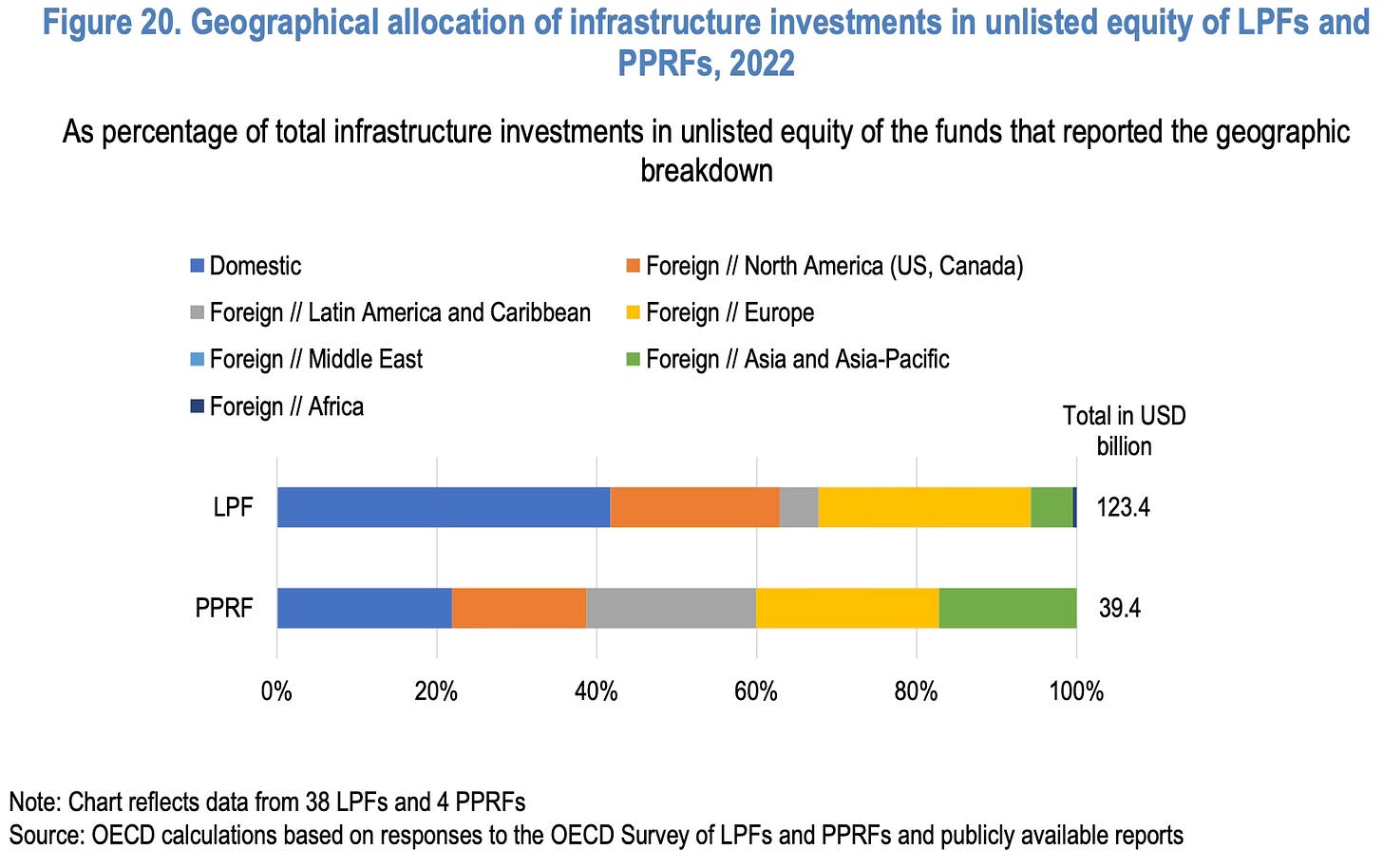

As seen above, infrastructure investments by LPFs are generally channelled through unlisted funds as equity.

However, PFs in developing countries appear to prefer bonds and listed equity. The three Indian funds, among the largest in the world, are invested in infrastructure almost completely through bonds and have no unlisted equity exposure. It’s most likely that Indian PFs continue to invest in infrastructure almost completely through bonds. The Israeli and Latin American funds appear to prefer both bonds and unlisted equity.

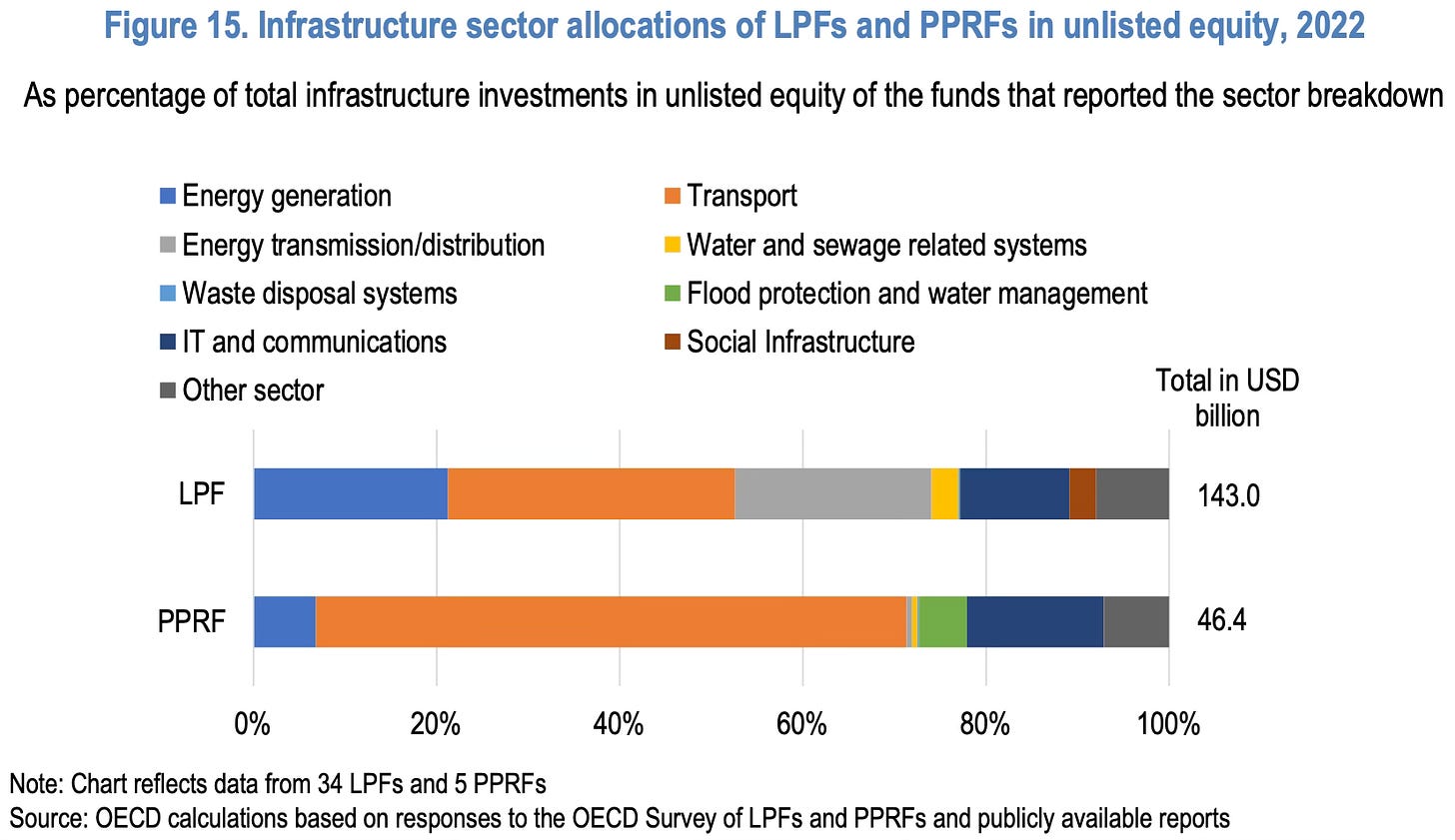

The sectoral exposures are almost completely in energy (conventional and renewable), transportation, and IT and communications, across countries. Social and urban utilities attract very little interest.

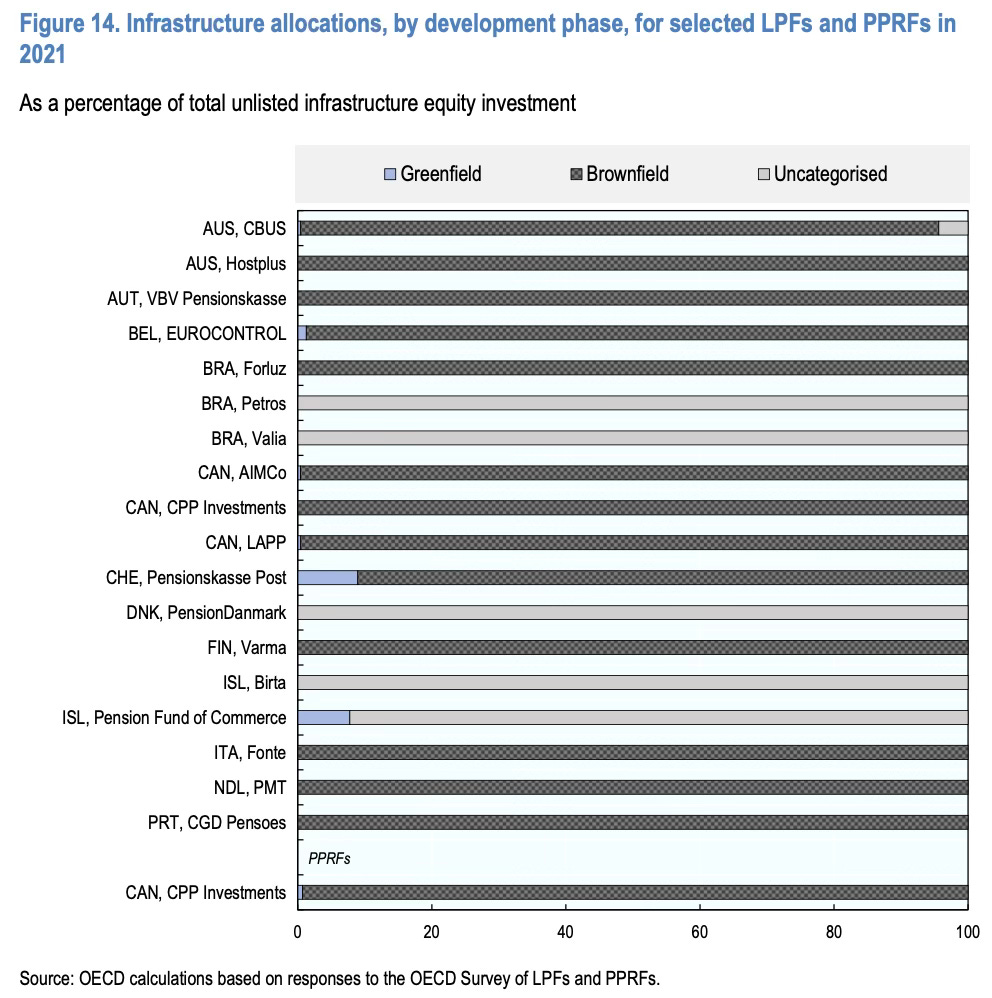

All PF investments in infrastructure flow to brownfield assets. Greenfield investments by PFs are negligible. This is understandable given the significant construction risks associated with infrastructure assets.

Most of PF investments are either domestic or confined to North America and Europe.

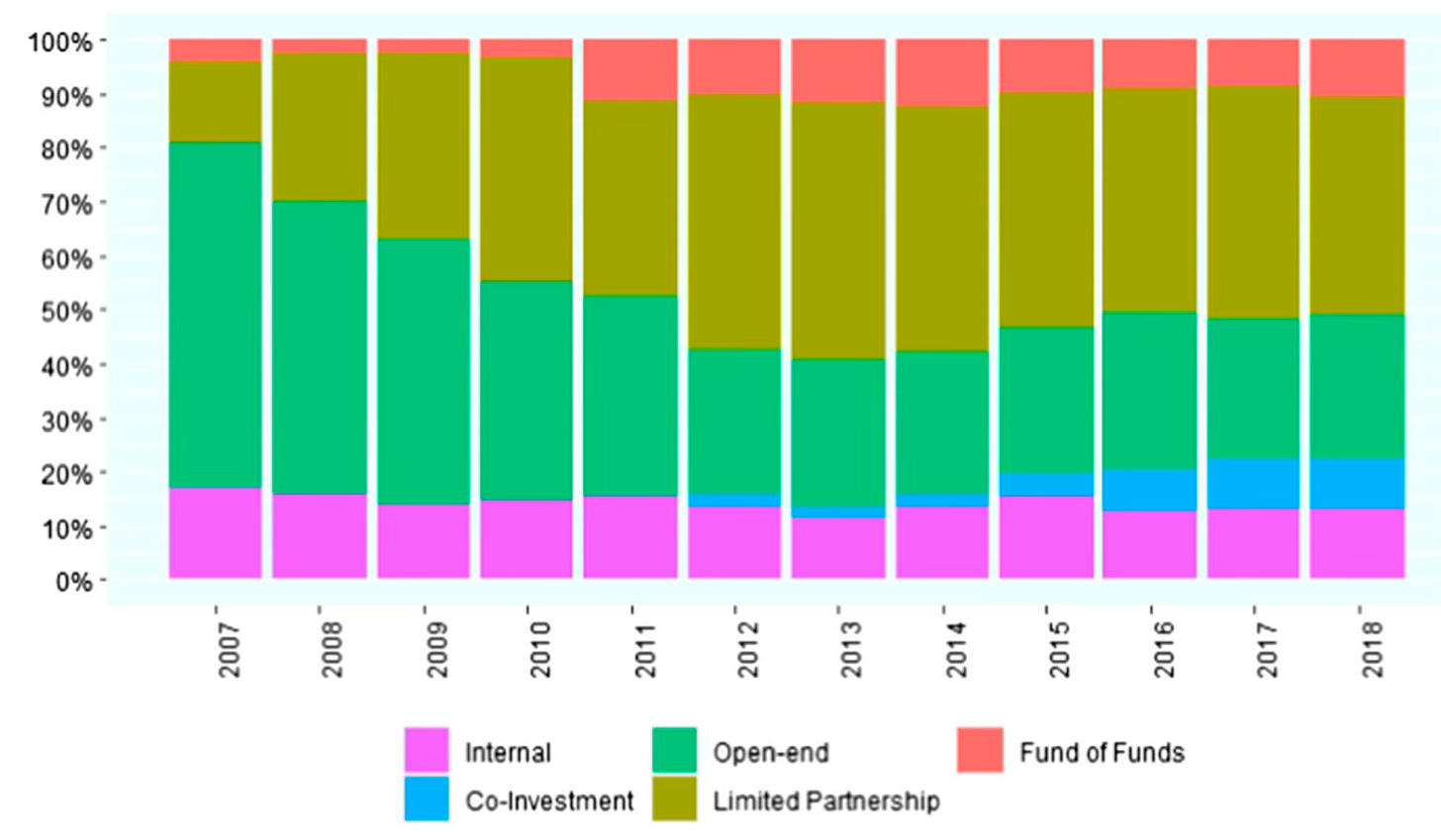

In terms of costs, there are five distinct approaches - internally managed (by an in-house investment team), private open-ended infrastructure funds, limited partners in closed-end funds with a fixed holding period, co-investment (with external management), and fund-of-funds. An analysis of the CEM database of 1132 defined benefit PFs over 1991-2018 period and covering $9.9 trillion AUM in 2018 (representing almost 25% of all global PF assets) shows the evolution of these approaches.

It can be seen that PF’s investing as LPs in infrastructure funds has emerged to become the most common investment approach, rising from 15% in 2007 to about 41% among all PFs. It’s also seen that co-investment approach has been rising.

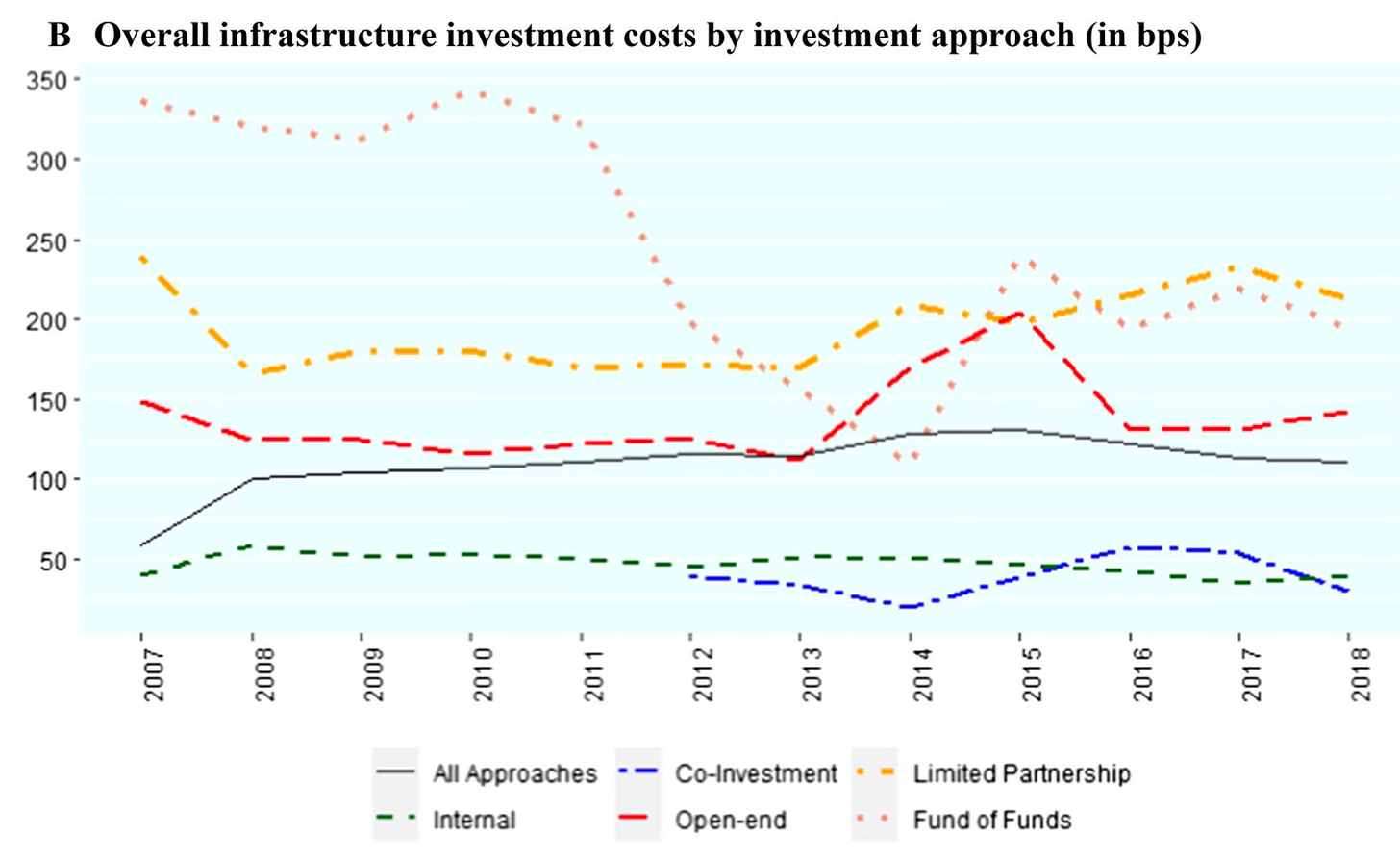

The investment costs associated with each approach shows that internal and co-investments are the cheapest approach, while LPs in closed-end funds and fund-of-funds (these together form the standard unlisted infrastructure funds of today) are the most expensive.

There’s an almost 150-200 basis points difference between the costs associated with internal and co-investment approaches and the traditional infrastructure funds route. This would apply not just to PFs, but all other institutional investors investing in infrastructure. It’s for this reason that the Canadian PFs have developed the institutional capacity for internal management of its investments and have generally avoided the infrastructure funds.

This is an excellent primer on India’s pension funds landscape. India’s pension fund assets are just 10% of the GDP, far below that of Western countries where it exceeds the GDP. But the total amount of around Rs 22 lakh Crore (as of March 2022), is a rapidly growing corpus. The regulatory norms restrict investments in alternative assets like infrastructure to 5%, though the actual exposure in most funds is far less. This is far lower than up to 26% permitted in countries like the UK, US, and Canada.

In light of the above, some suggestions:

1. From the evidence presented above, there are a few important takeaways for PFs in India. One, only a tiny share of PF capital will flow into the infrastructure sector. Two, PFs should maximise internal or co-investments, and in particular avoid infrastructure funds. Three, PFs should avoid greenfield investments and confine their infrastructure exposure to operating assets whose revenue streams are well established. Four, in the initial years, PFs should focus on power generation and transmission, transportation (highways, railways, ports, and airports) and IT and communication sectors. Five, PFs should try to diversify away from passive investments in infrastructure bond offerings and strive to invest in infrastructure equity through appropriate structures. Six, foreign PFs are unlikely to invest in significant amounts outside the developed countries.

2. India has a rapidly growing and massive pipeline of infrastructure projects that are attractive investment opportunities for its PFs. There’s a financial intermediation gap to channel PF capital to these infrastructure projects. Fortunately, there already experienced and credible institutional participants on both the supply and demand sides in India’s financial ecosystem who can bridge this intermediation gap.

The country has a long history of Development Finance Institutions (DFIs) involved in infrastructure sector. Sectoral DFIs like REC, PFC, and HUDCO have been around for decades and have strong performance track-record. In recent years, DFIs like NIIF, IIFCL, and NaBFID have been created as multi-sectoral DFIs. All these DFIs should be mandated to take the lead in de-risking and catalysing a mutually beneficial and completely professional co-investment approach in infrastructure with major domestic PFs and other institutional investors like insurers.

On the supply side, PFs like the EPFO, NPS, and APY and insurers like LIC and the four major public sector insurance companies, could be encouraged to take the lead in co-investing or investing in funds sponsored by the Indian DFIs.

To start with as a confidence building measure, the DFIs should invite the PFs and insurers to invest in their current portfolio assets and in the less risky among their pipeline of investment opportunities. These initial investments can be used to build confidence, especially among the institutional investors, besides documenting and institutionalising processes and protcols at both PF and DFI sides in the due-diligence and processing of such co-investments or co-funding.

3. The DFIs could, in turn, strike partnerships with banks who finance the vast majority of greenfield infrastructure assets and swap those loans into their portfolios, co-investing or co-funding with PFs/insurers. This would be an institutionalised take-out financing model which addresses multiple problems that currently bedevil the market for infrastructure finance - the higher cost bank loans could finance the risker but short-term loans of the construction phase; asset-liability mismatches faced by the banks can be bridged with the take-out of their loans by DFIs; the DFIs in turn would have access to a standard pipeline of institutional long-term capital from insurers and PFs.

4. State-led initiatives to finance infrastructure have always been a feature of the infrastructure sector even in developed countries. DFIs have been central to the intermediation of long-term capital into the infrastructure sector across the world.

Public policy engagement in the economy is becoming more active across the world, as seen in the surge in industrial policies especially in the developed world. In infrastructure itself, governments in several advanced countries have been trying to crowd-in long-term capital into infrastructure. A recent article in The Economist pointed to the rise of pension fund nationalism and wrote about government efforts across the world to channel pension funds to finance infrastructure investments.

Rachel Reeves, Britain’s new chancellor… on July 8th… said that she wants the country’s pension funds “to drive investment in homegrown businesses and deliver greater returns to pension savers”… Her predecessor, Jeremy Hunt, set the ball rolling by mandating that defined-contribution pension funds will have to disclose the scale of domestic investments by 2027. Other countries are joining in. Stephen Poloz, a former Governor of the Bank of Canada, is looking at how to increase pension fund investments in domestic assets on behalf of the Canadian government. Enrico Letta, a former Italian Prime Minister, recently urged in favour of an EU-wide auto-enrolment pension scheme that could be funnelled into green transport and energy infrastructure.

5. This partnership will require long-term investment of the highest-level commitment and effort by institutional stakeholders at both the supply and demand sides. It must be supported with active co-ordination and facilitation by the respective Departments in the Ministry of Finance in the Government of India. This would require stable long-term leadership and 2-3 champions leading the cause for at least five years to lay a strong enough foundation to allow the model to take off.

If done effectively, catalysing a mutually beneficial co-investment/co-funding model between India’s DFIs and PFs/insurers can become a defining innovation in crowding in the rapidly growing pool of long-term capital to finance an equally fast-growing portfolio of infrastructure assets. It can be a model for pension funds in other countries grappling with the high costs of reliance on external fund managers like infrastructure funds but also don’t have the capabilities to manage the funds internally.

6. This could be part of a basket of initiatives within India to shape the market landscape in infrastructure financing. Apart from DFI’s partnering with PFs and insurers to channel long-term capital, India could show the way with initiatives to de-risk bank lending to infrastructure, structure infrastructure credit guarantees through DFIs and bring together a coalition of banks to lend against them, revise the credit rating methodologies, and lower the cost of capital by revising capital adequacy ratios based on actual history of credit defaults in the sector.

These reforms are also central to addressing the current hot-button issue of mobilising capital for climate change mitigation. India could position itself as the pioneer in plumbing reforms to attract long-term capital into climate finance.

7. There’s already great interest among global alternative investment funds (AIFs) and intense associated lobbying to have PFs invest in infrastructure funds. But Indian PFs should avoid following the investment approach of relying on large global infrastructure funds. Instead, India should take a leaf out of its pioneering role in several areas of private investing in infrastructure, including its own PPP models in highways and power generation. As aforementioned, India should seek to create its own approach to PF investments in infrastructure.

8. Finally, as you can see, the idea itself is simple and can be articulated, support mobilised, and got approved without much effort. The challenge is in its implementation - the commitment and effort to develop the model, pursue a few initial investments and de-risk it while also iterating to address the emerging flaws and problems with the model, monitoring and supervision to prevent the abuse of the model; and coordination and facilitation by the Government departments concerned are all critical ingredients and require long-drawn, painstaking, and detail-focused effort by a capable and committed team with visionary leadership.

No comments:

Post a Comment