A Bloomberg series (this and this) chronicles US hospital chains' widespread use of Nurse Practitioners (NPs) in primary care to emergency rooms. NYT has a two-part series (this and this) on how pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) are driving up drug prices and forcing out independent drug stores across the US.

The four articles are a case study on how profit maximisation incentives in sectors like health care distort incentives, erode service quality, hurt consumer welfare, and inflict pain on customers and communities.

The Bloomberg series illustrates the example of Hospital Corporation of America (HCA), a $84 billion for-profit, which is the largest hospital chain in the US, with its over 180 network hospitals across the country having treated over 1.9 million patients in 2022 alone.

It has gone the farthest in using NPs to maximise efficiencies.

Busy ERs are constantly triaging, determining where the physicians on duty are most needed. And nurse practitioners have significant responsibility and authority—perhaps more than many patients realize. In important respects, they’re now at the center of health care in the US… There are already more than 300,000 nurse practitioners, and that figure is rising far faster than the number of doctors. In 2014 there was 1 NP for every 5 physicians and surgeons in the US, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Last year the ratio was 1 to 2.75. The gap is going to shrink further still: Nurse practitioner is the fastest-growing profession in the country, and the ranks are expected to climb 45% by 2032.

After getting an advanced degree—typically a master’s or doctorate in nursing—and an additional license, nurse practitioners are allowed to treat patients in many of the same ways medical doctors do, including diagnosing ailments and prescribing medications. The shift has many benefits. For patients, more clinicians means getting care sooner. (The average wait time for an appointment with a physician is at an all-time high of 26 days.) For health-care organizations, NPs are cheaper to employ than physicians, and under some circumstances the organizations can bill insurers for their time at physician rates. The NPs themselves can get more pay, more prestige and a better work-life balance than registered nurses, which many NPs formerly were.

Such demand creates its own supply albeit with serious distortions

The problems result from the surging number of programs, which graduate thousands of NPs a year without adequately preparing some of them to care for patients. The former director of the largest NP program in the country says she can’t recall denying acceptance to a single student. More than 600 US schools graduated students with advanced nursing degrees in 2022, according to US Department of Education data. That’s triple the number of medical schools training physicians. More than 39,000 NPsgraduated in the 2022 class, according to the AANP, up 50% from 2017.

Unlike the training program for physicians, education for NPs isn’t standardized. Some candidates attend in-person classes at well-regarded teaching hospitals, but a much larger number are educated entirely online, sometimes via recorded lectures that can be years old. Interaction with professors is often limited to emails and message boards. These circumstances make the required clinical portion of an NP’s education even more important—but compared with doctors’ residencies, those stints are brief, and students say they’re of wildly variable quality. In 2022 the advanced nursing programs that awarded the most degrees were offered by institutions that deliver the classroom portion of instruction primarily over the internet…

Early waves of NP students were often experienced registered nurses seeking to increase their skills and responsibilities. But as demand spiked, more schools began offering “direct entry” programs that accepted students with a bachelor’s degree in unrelated fields. Today the fastest among them can prepare students for NP licensure exams in three years of education that encompasses a bachelor’s in nursing, registered nursing licensing (all NPs have to become RNs, even if they haven’t yet worked in the field) and a master’s in nursing. In 27 states, licensed graduates are allowed to treat patients and prescribe drugs with no physician oversight, even if they have no prior nursing experience… With a separate license from the Drug Enforcement Administration, NPs can also prescribe controlled substances. This license has made NPs particularly attractive to telemedicine companies… Students must obtain 500 clinical hours to graduate. That’s less than 5% of the amount required of medical doctors before they can practice medicine.

Fundamentally, the demand for NPs is driven by unit economics

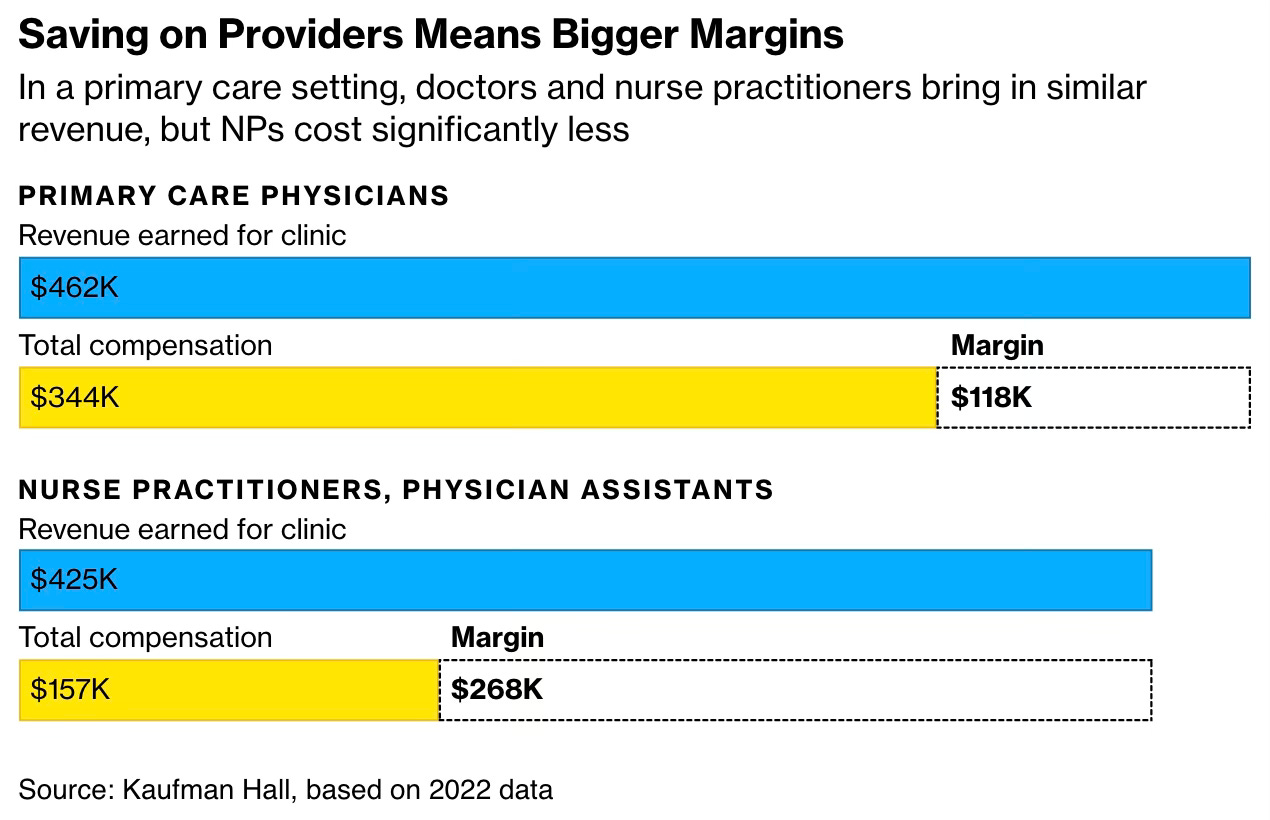

Physicians are in short supply, and NPs can fill the gap. There’s also a financial motivation. A primary care physician costs $344,308 a year, whereas a primary care NP costs about $156,546, according to 2022 data compiled by Kaufman Hall, a health-care consulting company. Yet primary care NPs can generate $424,979 of direct revenue a year, only $37,000 less than a physician. Put another way, NPs are twice as profitable.

The largest US hospital chain, HCA, a for-profit firm, is illustrative of the extreme dependence on NPs.

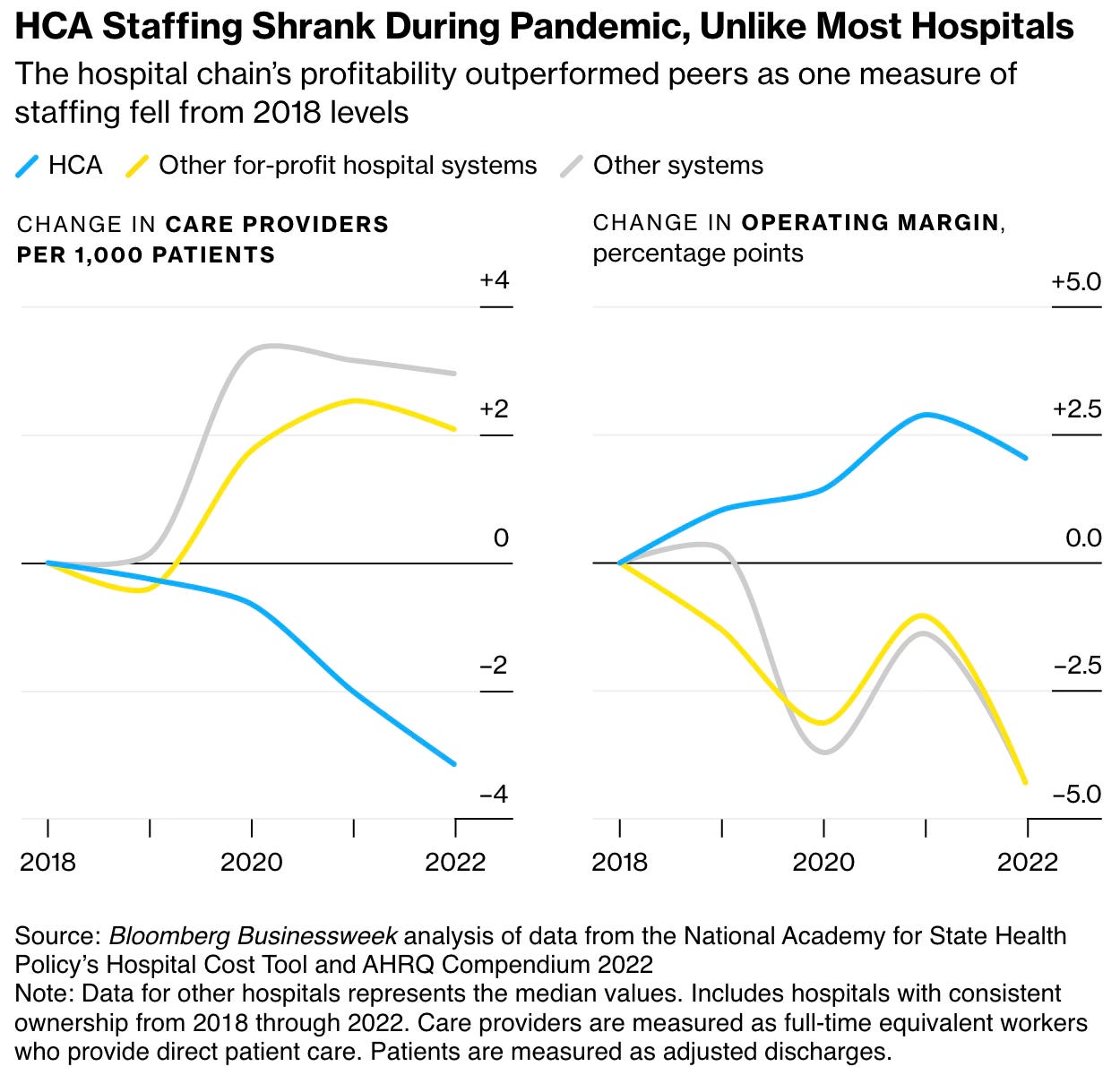

This staffing pattern has soundly rewarded HCA’s shareholders.

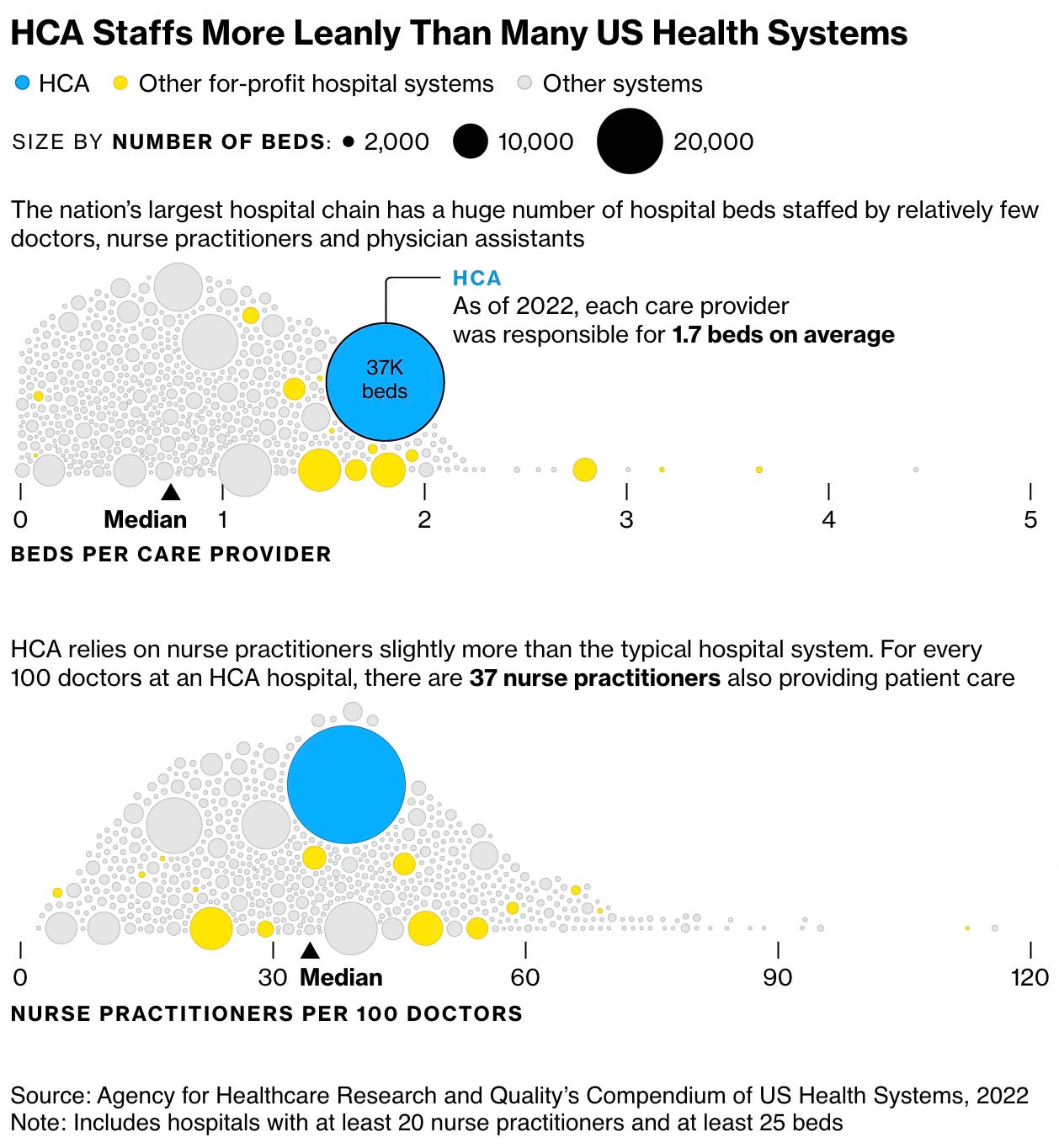

The company has one of the lowest ratios of physicians and advanced practice providers (a catchall term for nurse practitioners and physician assistants) per bed among more than 600 US health-care systems that the federal government tracks. Registered nurses and other support staff aren’t included in that tally, but other government data that accounts for a wide range of roles also show HCA tends to staff leanly. It’s one reason HCA is widely regarded as one of the most efficient operators in its industry, with the largest profit margins of any American hospital chain that trades on the stock market. Shares have returned fivefold in the past decade, even after falling recently amid concerns about reduced Affordable Care Act subsidies.

With the advances in technology and data analysis, it has now become possible, in theory at least, to disaggregate the job of doctors and parcel many parts out to NPs and others.

Some HCA staff say the company is merely going where the data is taking it—a future with fewer medical doctors. This trend has been evident for years in primary care: Fewer physicians are pursuing it, and NPs have filled that role for many Americans. HCA staff who spoke to Businessweek said that shift is now underway in other practice settings. In many of them, “we will get to a point where there will be no physicians left,” says one executive who recently left HCA after several years at its Nashville headquarters and asked for anonymity to speak on the sensitive topic. “You just won’t have physician oversight, because we won’t have the supply.

The power of economies of scale and search for cost-minimisation has been a big driver of the historical evolution of HCA.

The Hospital Corp. of America was co-founded by Dr. Thomas Frist Sr. more than a half-century ago in Nashville. Frist, a cardiologist and internist, complained he had trouble getting his patients into nearby hospitals, so he opened his first for-profit hospital, a squat, five-story facility called Park View, as a remedy. Frist’s son Thomas Jr. saw the power in economies of scale, and the company started gobbling up more facilities. American health care has been bending Frist’s way ever since, and HCA’s value has soared. Thomas Jr. has become the world’s 56th-richest man, with a $30 billion fortune largely derived from his HCA shares. His younger brother, Bill, became majority leader in the US Senate, where he helped pass the Medicare Modernisation Act of 2003, allowing retirees to receive benefits through private insurers. The company’s gravitational pull has turned Nashville into the world’s unofficial headquarters of for-profit health care, drawing more than 900 companies to the area. Its own holdings have exploded, too, with more than 180 hospitals across several states, and a toehold in the UK.

Within that portfolio, Chippenham and its affiliated facilities are a powerhouse, the company’s fifth-largest by revenue, federal data show. Closely watched from corporate headquarters, Chippenham executives have frequently been plucked for bigger roles, charged with running dozens of hospitals in HCA’s system. Big revenue doesn’t necessarily mean big resources. In Richmond, Chippenham’s emergency room has a troubling reputation. Current and former employees describe limited staffing and resources that guarantee they’ll be caring for patients in hall beds and in the waiting room on a nightly basis. Patients describe waits stretching for several hours amid blood smears and vomit bags… traveling nurses who have worked at several facilities told Businessweek that Chippenham stands out for its chaos and lack of resources and staff. Nurses in the hospital’s intensive care units describe getting “tripled” multiple times a week—being responsible for three patients at a time. The standard is two… Some of the nurses said they’d worked at nonprofit facilities that never tripled them. The problems were so well known that even some community members were wary.

HCA’s acquisitions are good illustration of how its practices have transformed the healthcare sector for the worse (in this case dramatically worsening the quality of a highly reputed non-profit).

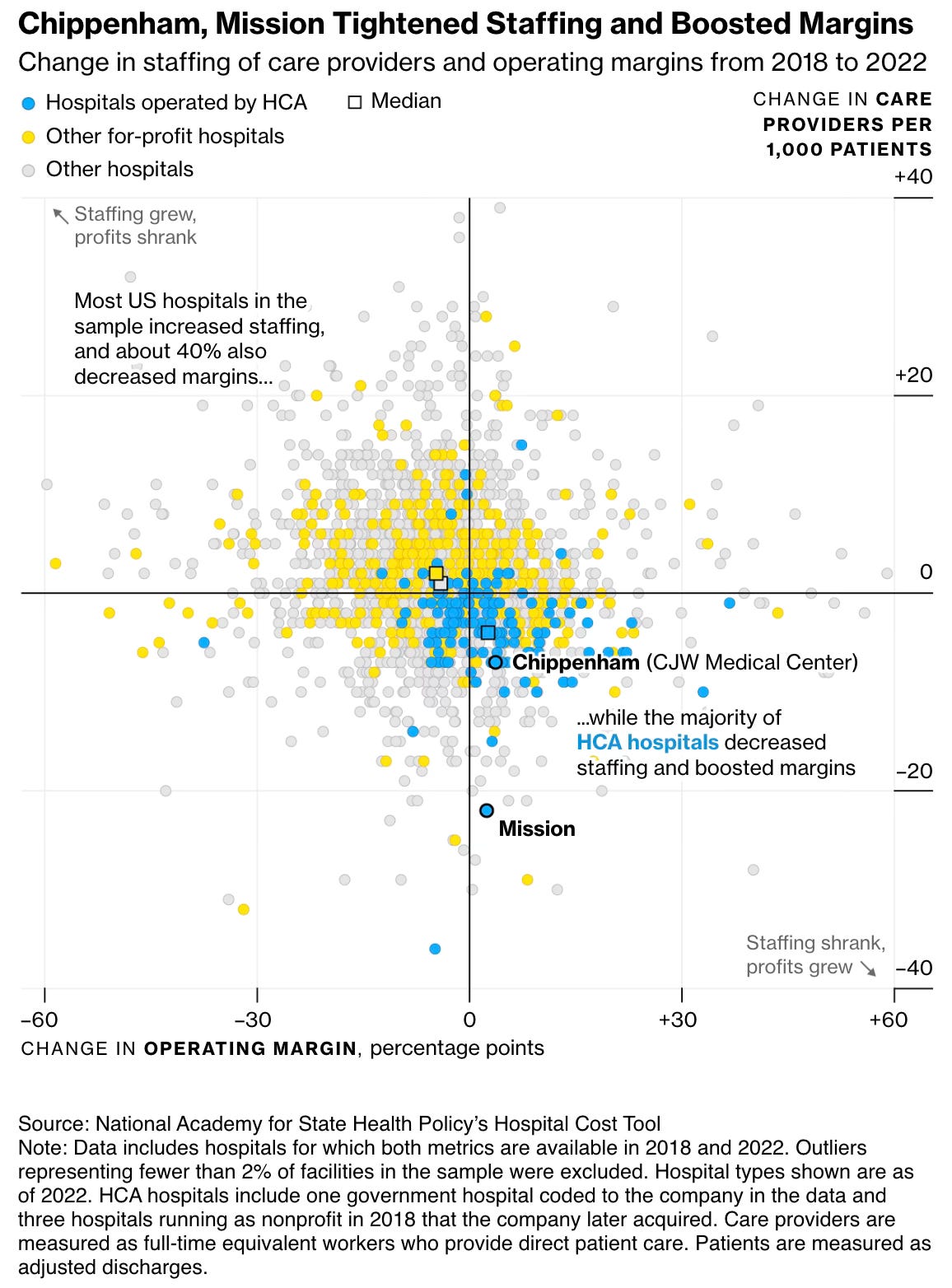

HCA’s makeover of Mission Health in Asheville, North Carolina, offers a vivid example of how the company’s staffing strategies can affect caregivers, patients and the company’s bottom line. In 2019, HCA paid about $1.5 billion for Mission Health, a nonprofit system with several facilities and a reputation as one of the Southeast’s premier health-care centers. HCA executives promised to preserve Mission’s quality while boosting profits by using the corporation’s size to deliver better “purchasing power and back-office efficiencies.”

Soon, HCA began drastic staff reductions at the system’s flagship facility, Mission Hospital, and conditions deteriorated rapidly, according to a lawsuit filed by the state attorney general. Wait times in the emergency room swelled, nurse-to-patient ratios in ICUs often fell to half the state minimum, and surgeons reported they frequently lacked sterile medical instruments because of cuts to the cleaning staff, the lawsuit said. When HCA executives brushed aside complaints from Mission board members and employees, two-thirds of its physicians left, according to a research paper published by Mark Hall, director of the Health Law and Policy Program at Wake Forest University. Mission’s emergency room was so severely understaffed that it jeopardized patient safety, a federal investigation concluded…

The drastic reductions in Mission’s labor costs were a boon to the hospital’s finances. In the four years before the sale, Mission earned an average of $38 million in profit from patient care. In 2022, Mission’s profit reached $96 million, driven primarily by “sharply reduced staffing for patient care under HCA,” according to Hall’s research.

This graphic captures how HCA increased profitability across its network hospitals using these practices.

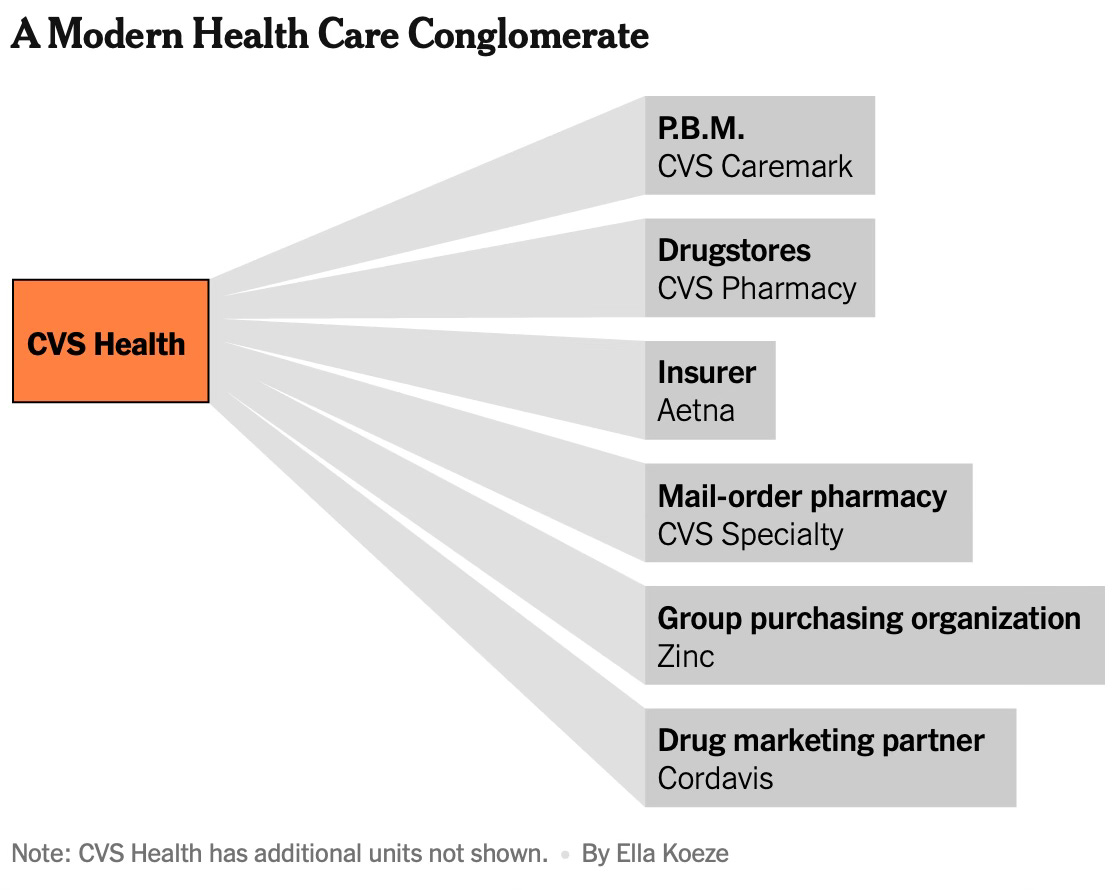

The PBMs intermediate the insurance for prescription drugs by negotiating with drug companies, paying pharmacies, and helping decide which drugs patients can get at what price. The three largest ones - CVS Health, Cigna and UnitedHealth Group - oversee prescriptions for more than 200 million Americans and control nearly 80% of the market, up from less than 50% in 2012.

P.B.M.s sometimes push patients toward drugs with higher out-of-pocket costs, shunning cheaper alternatives… Even when an inexpensive generic version of a drug is available, P.B.M.s sometimes have a financial reason to push patients to take a brand-name product that will cost them much more… They often charge employers and government programs like Medicare multiple times the wholesale price of a drug, keeping most of the difference for themselves. That overcharging goes far beyond the markups that pharmacies, like other retailers, typically tack on when they sell products. The largest P.B.M.s recently established subsidiaries that harvest billions of dollars in fees from drug companies, money that flows straight to their bottom line and does nothing to reduce health care costs.

The P.B.M.s, which are responsible for paying pharmacies on behalf of employers, are driving independent drugstores out of business by not paying them enough to cover their costs. Small pharmacies have little choice but to accept these lowball rates because the largest P.B.M.s control an overwhelming majority of prescriptions. The disappearance of local pharmacies limits health care access for poorer communities but ultimately enriches the P.B.M.s’ parent companies, which own drugstores or mail-order pharmacies. P.B.M.s sometimes delay or even prevent patients from getting their prescriptions. In the worst cases, patients suffer serious health consequences… Even people who don’t take prescription drugs end up paying higher insurance premiums and taxes as a result of inflated drug costs… If they were stand-alone companies, the three biggest P.B.M.s would each rank among the top 40 U.S. companies by revenue.

This description of the evolution of PBMs is instructive.

P.B.M.s have been around since the late 1950s. They initially handled requests mailed in by pharmacies and patients seeking reimbursement for the costs of prescription drugs. Over the decades, P.B.M.s have had different owners, including drug makers and large chains of pharmacies… The modern P.B.M. emerged in 2018. The giant health insurers Aetna and Cigna were trying to achieve the growth demanded by Wall Street. They sought to merge with the P.B.M.s, whose profits were soaring. Aetna and CVS combined. Cigna bought Express Scripts. (UnitedHealth had built its own P.B.M.)

It would turn out to be a seminal moment, one that would rapidly and radically change the American health care system by further shifting power into the hands of giant conglomerates and away from employers and patients. Today, P.B.M.s feed off a system where everything is extraordinarily complicated — including how much a drug actually costs.

The PBMs have evolved business models that allow them to obsfuscate and capture a significant share of the discounts obtained from drugs manufacturers. They have set up subsidiaries to negotiate discounts with drug manufacturers.

The creation of the subsidiary, Emisar, has allowed UnitedHealth to retain billions of dollars of those savings, without having to share them with employers. Emisar and similar subsidiaries established by Express Scripts and Caremark are known as group purchasing organizations, or G.P.O.s. They were created, starting in 2018, amid growing pressure from employers to share with them more of the manufacturers’ discounts. In response, the P.B.M.s altered their business model. The new subsidiaries still received rebates from drug companies, and they passed on those rebates to the P.B.M.s, which in turn sent the savings to employers. But the G.P.O.s also began imposing new fees on drug manufacturers.

Because those were fees, not rebates, and because the fees were technically collected by a different company, the P.B.M.s weren’t contractually obligated to share them with their clients. And the P.B.M.s could truthfully say that they were returning to employers almost all of the drug companies’ rebates. They didn’t have to mention the fees… In 2022, P.B.M.s and their G.P.O.s pocketed $7.6 billion in fees, double what they were bringing in four years earlier, according to Nephron, a consulting firm… Emisar operates mainly in Ireland, and Express Scripts’ Ascent is in Switzerland, which means their profits are taxed at much lower rates than if they were generated in the United States… When drug companies paid more in fees, they offered less in rebates… Employers… receive rebates. But they can’t see the billions of dollars in fees that the G.P.O.s take for themselves…

The conglomerates that own the big P.B.M.s also own pharmacies. CVS has thousands of drugstores. And all three operate warehouse-based pharmacies that send prescriptions to patients through the mail. The three P.B.M.s push, and sometimes force, patients to use their pharmacies, whether mail-order or, in CVS’s case, the physical drugstores. One common strategy is to not allow patients to receive 90-day supplies of drugs if they fill prescriptions at outside pharmacies… One surefire way for the P.B.M. or its in-house pharmacy to profit is to charge thousands of dollars more than what a drug costs… The steepest markups often involve generic versions of expensive medications for conditions like cancer.

This article shows how PBMs have been systematicallt underpaying small pharmacies (how much the drugstores are reimbursed for medications), driving them out of business. This, in turn, benefits the largest PBMs who also run competing pharmacies.

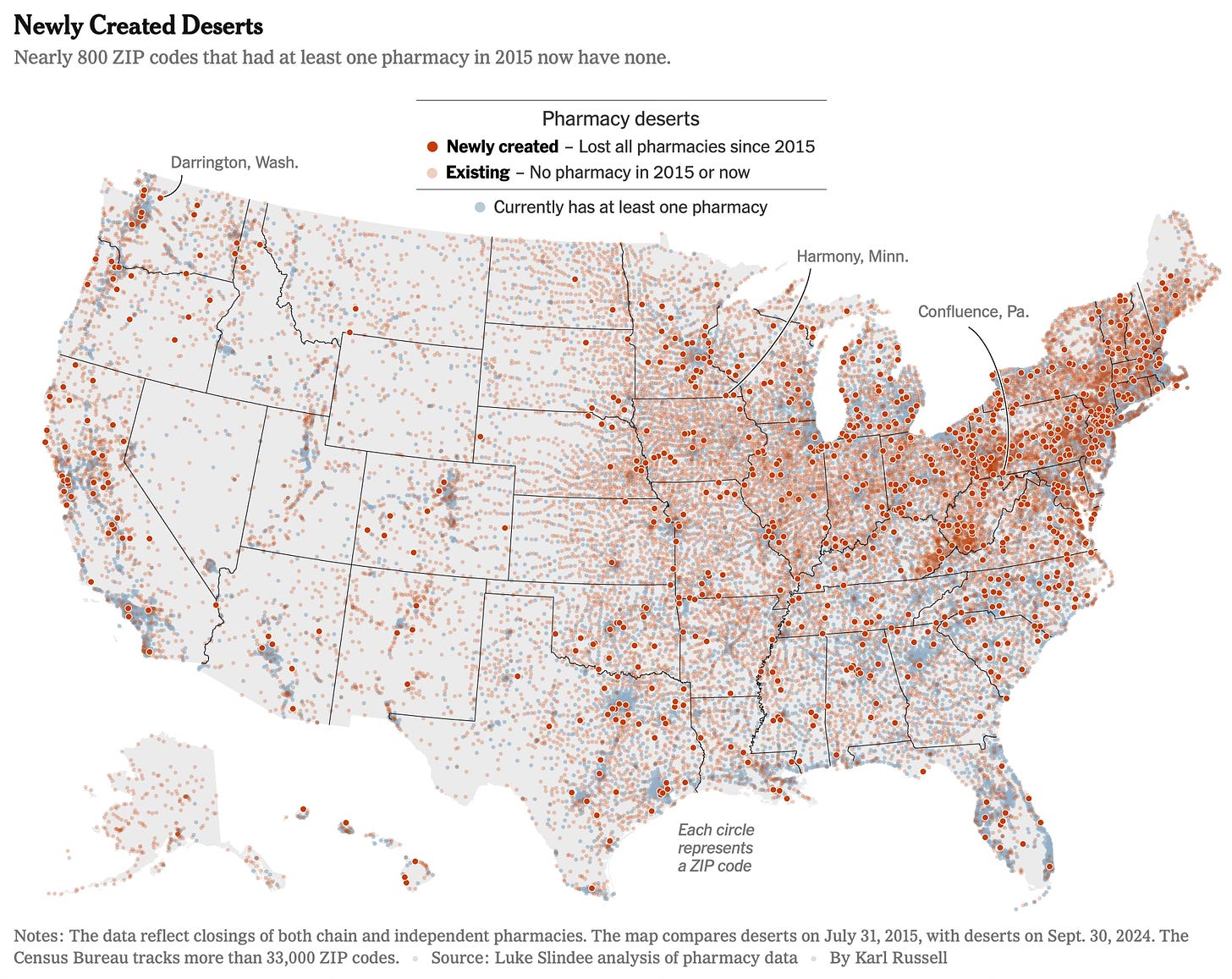

In every state, The Times identified at least one example since 2022 in which an independent drugstore closed and the pharmacist blamed P.B.M.s. In some states, like Pennsylvania, such closings have become routine. They have disproportionately affected rural and low-income communities, creating so-called pharmacy deserts that make it harder for residents to get prescriptions and medical advice.

One study, paid for by a pharmacy association, found that the markup that P.B.M.s were charging on brand-name drugs was 35 times higher when the drugs were sold through their own mail-order pharmacies than when the drugs were sold by independent drugstores. Government studies have identified a similar phenomenon… The benefit managers decide which pharmacies are available to patients through their insurance. To be included, a pharmacy must agree to a contract with the P.B.M. that details the formula for how much the pharmacy will be reimbursed for drugs… Because the top P.B.M.s collectively control the overwhelming majority of prescriptions, pharmacies that forfeit their business could not survive.

The closure of small pharmacies have left communities without any drug stores.

Nearly 800 ZIP codes that had at least one pharmacy in mid-2015 now have none, according to an analysis of pharmacy data by Luke Slindee, a consultant who has been tracking pharmacy closings around the country… When small drugstores close, communities can be harmed in ways that are hard to measure. Getting your flu shot becomes less convenient. As residents grow accustomed to traveling long distances for their medications, they do more of their other shopping far away from home, draining revenue from local businesses. Relying on mail-order pharmacies deprives customers of an easy way to get advice from a trusted local pharmacist… Research has found that after pharmacies close, their older customers are less likely to consistently fill their prescriptions and end up missing doses… Even when a small pharmacy stays in business, low reimbursement from P.B.M.s can make it harder for its customers to get their medications. Many small drugstores sidestep their contracts with P.B.M.s and decline to dispense certain medications — especially high-cost brand-name products for conditions like diabetes and obesity — because they lose money on them. Customers must go elsewhere.

Some observations

1. The evolution of PBMs from being small payment-handling intermediaries to mega-firms with interests all along the prescription drug supply chain has not only not delivered the promised benefits in terms of efficiencies and value sharing across the chain but has also left patients, employers, and insurers with higher costs. Similarly, the emergence of massive hospital networks, far from transmitting benefits across stakeholders from economies of scale, has engendered perversions like substituting away from higher-cost doctors towards lower-cost NPs, besides seriously worsening the quality of care.

2. There’s a fundamental problem with the pure financial metrics-driven business growth strategy in sectors where quality of service delivery is critical. The exclusive and obsessive focus on financial metrics will invariably lead the management down the path of cost-cutting and revenue maximisation. In this efficiency maximisation drive, and especially in large systems and where quality of service is critical, it’s hard not to avoid skimping on things that are central to quality.

The example of the increased use of NPs across hospital networks in the US is yet another example on the perils of such efficiency maximisation. As the articles show, the disaggregation of the doctor’s work and parcelling some parts of it out to NPs ends up seriously eroding the quality of care delivered. Besides, the sharp differential in the costs of doctors and NPs will invariably incentivise pushing the boundaries on substituting the doctor with the NP.

3. Firm size in itself (and the associated detached and impersonal management) is a problem in services where quality is critical. In such services, personalised care and engagement is a critical value proposition. No technological innovation or business structure can be a substitute. The small hospital networks and independent pharmacies bring attributes critical to the effectiveness of service quality that the large firms cannot replicate.

4. A market dominated by a few large conglomerate firms will invariably distort incentives and engender dynamics that will hurt consumer welfare. Vertical and horizontal integration with opaque ownership and accounting disperses costs and accountability across the conglomerate. It engenders market failure and is a recipe for perversions like price gouging, cross-selling, profit maximisation etc.

In general, the ownership and management structure of massive PBMs and hospital networks will tend to generate excessive efficiency and profit-maximisation impulses that detract from quality and consumer welfare. It’s very difficult, even impossible, to achieve the balance between shareholder and stakeholder value maximisation, and the latter invariably falls aside with time. It’s almost the inexorable logic of capitalism, one which gets exacerbated by private equity ownership.

5. The rapid expansion of the supply side in any sector where service delivery quality is critical is fraught with problems. It resonates with the troubled examples of multiple instances when state and central governments in India have sought to rapidly increase the institutions (and seats) offering engineering, medical, nursing, and other professional courses.

When done at scale and too quickly, blended learning and online instruction approaches are likely to struggle to meet the fidelity requirements. Baumol’s cost disease is real in sectors like education and there are hard limits to the application of technology to address the problem.

6. The example of HCA should serve as a cautionary tale for those who preach the ideology of the superiority of for-profit companies. The degeneration in the quality of service of Mission Health, a reputed non-profit hospital network, after being bought by HCA and turning for-profit is an apt case study.

It’s an oft-repeated ideological argument in countries like India that its education system can be improved by permitting for-profit institutions. The US for-profit hospital networks and Nursing Colleges are good examples of the problems with the introduction of profit incentives to sectors like healthcare and education.

No comments:

Post a Comment