The latest sector where Chinese manufacturers are gradually establishing their global dominance is that of passenger vehicles, especially electric vehicles (EVs). NYT has an excellent article that chronicles how Chinese car makers have come to dominate the global market.

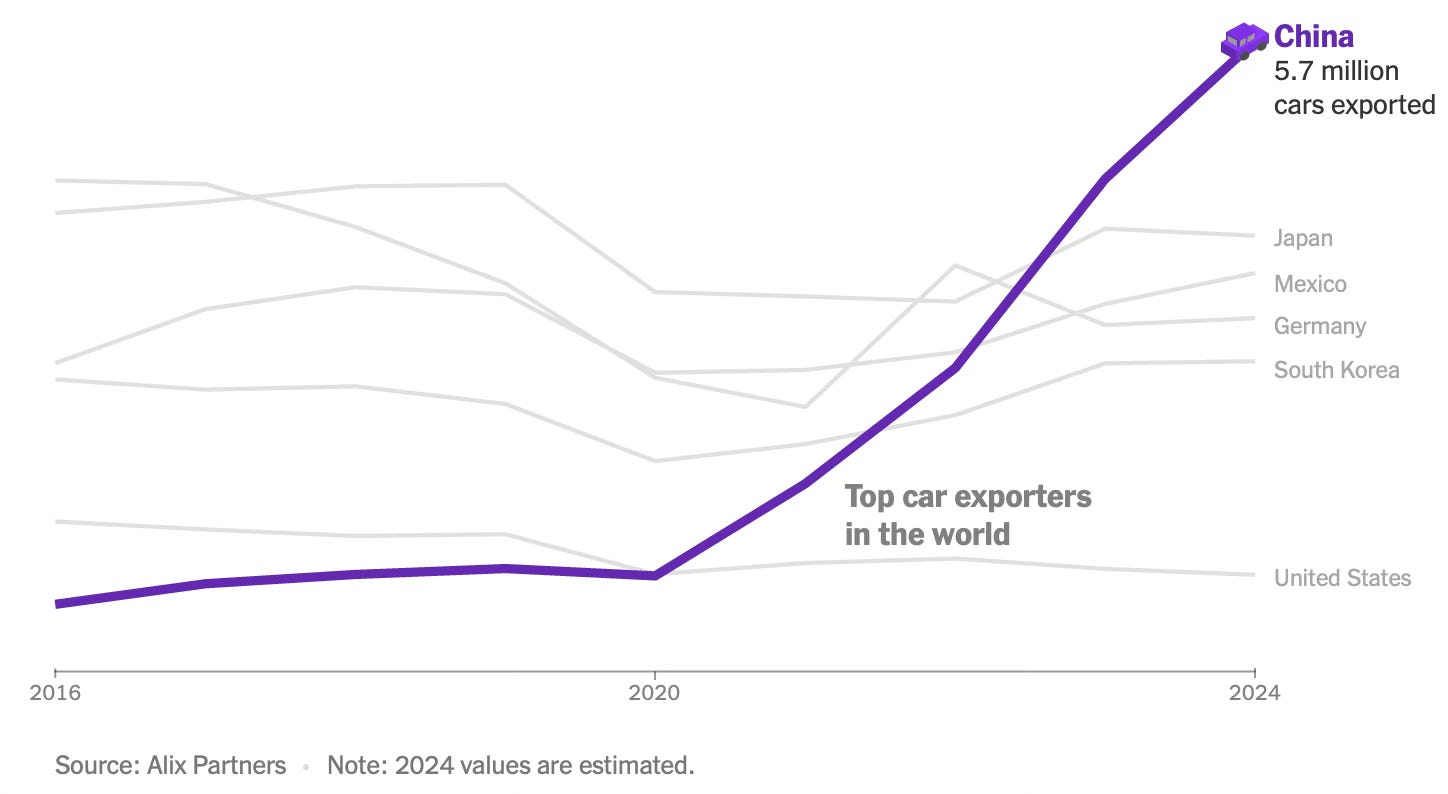

Since 2020, Chinese car makers have taken the world by storm.

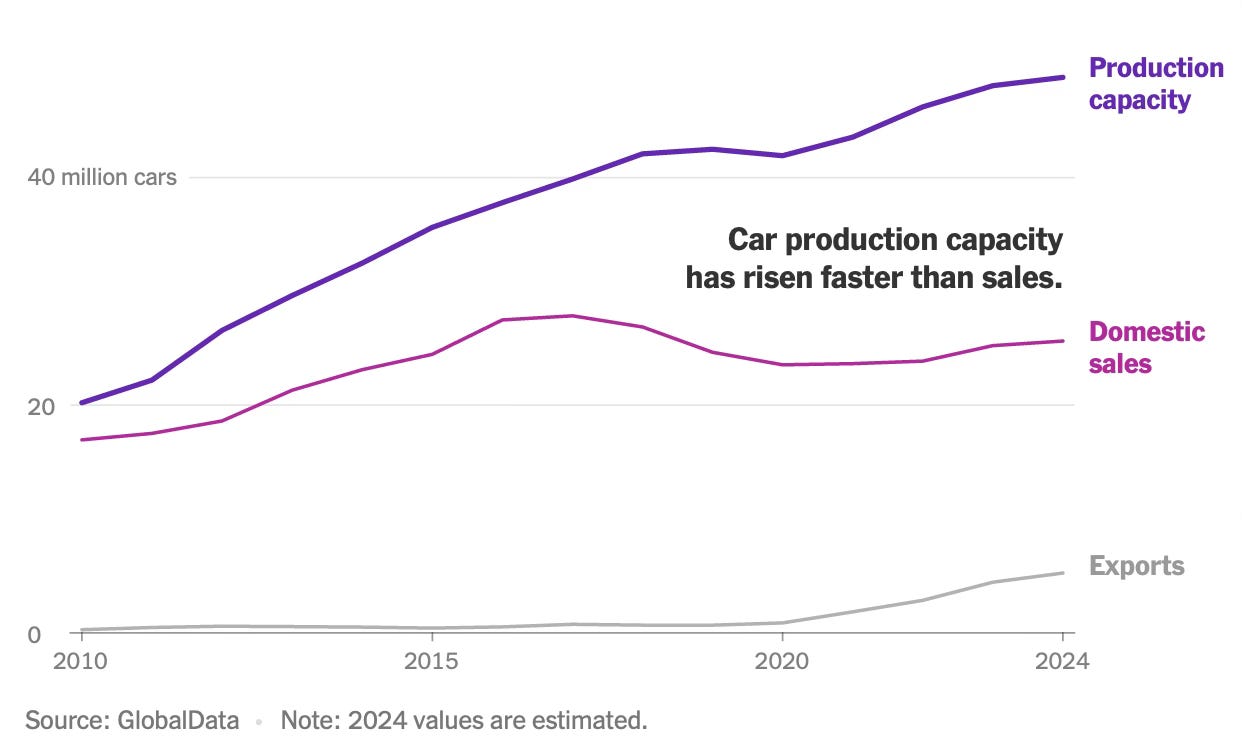

On the back of industrial policy, Chinese firms have ramped up production capacity aggressively, so much so that it’s now more than double the domestic demand. There are apparently more than 100 factories that can churn out 40 million ICE vehicles a year.

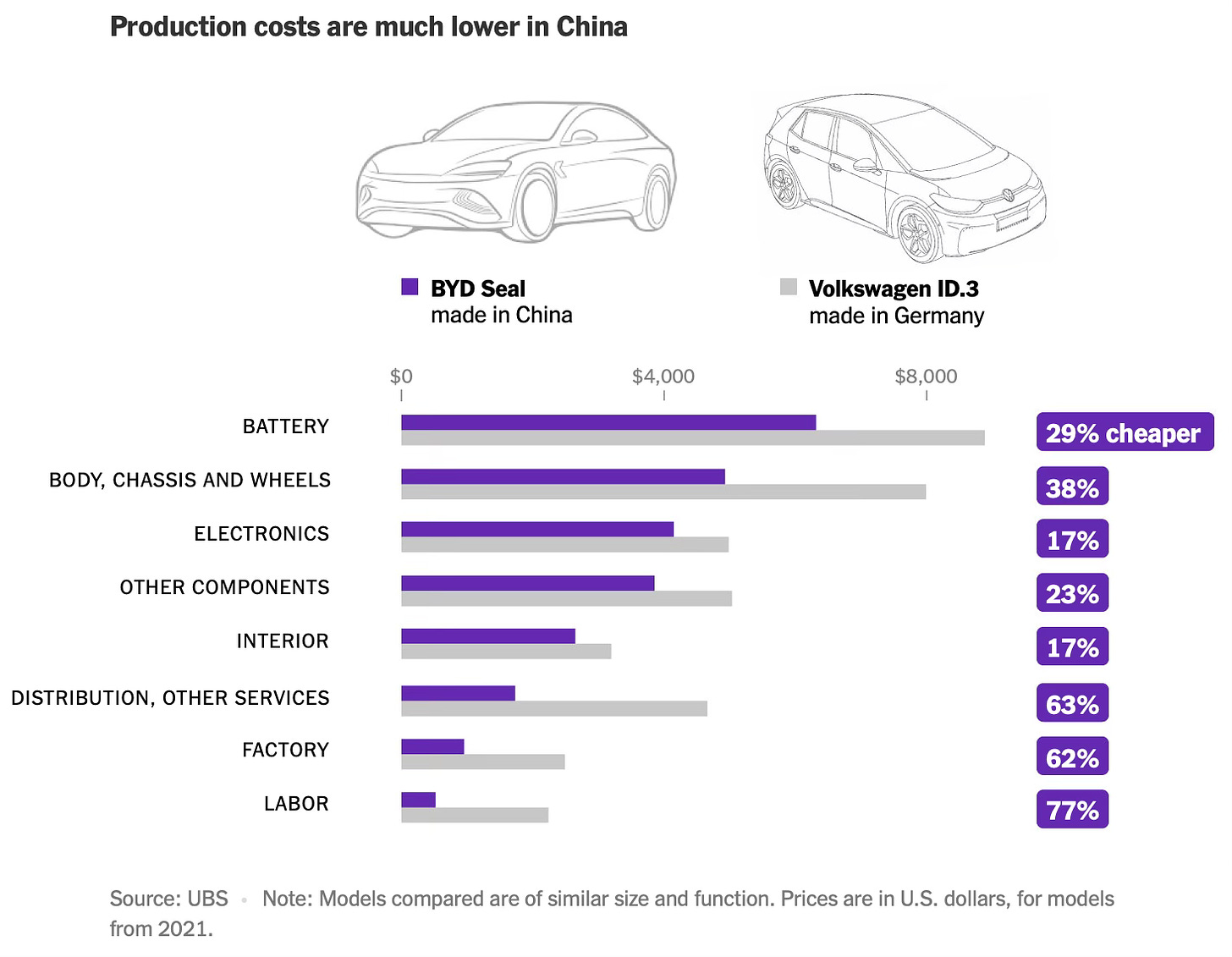

The large subsidies, economies of scale, and the discounted dumping of excess capacity mean that Chinese car makers easily outcompete their rivals.

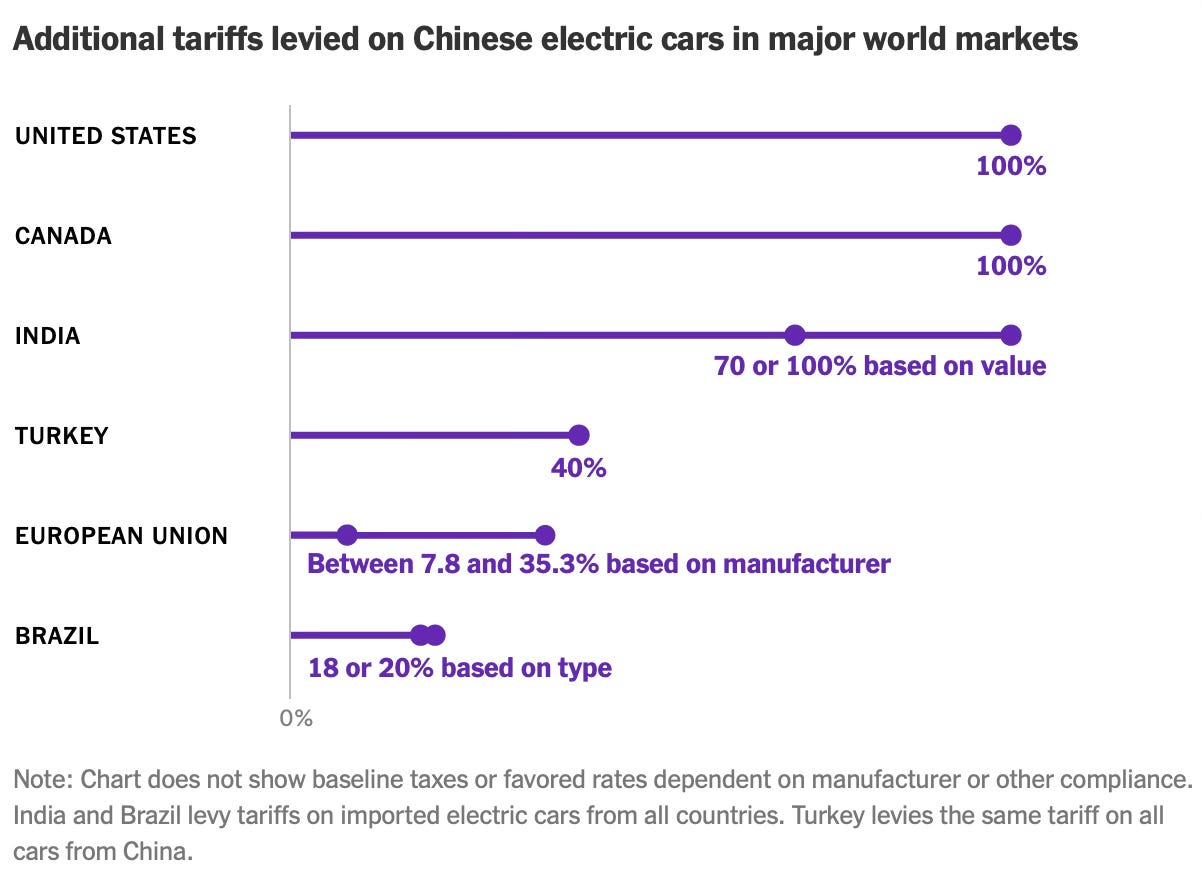

And it invariably triggers tariffs from trade partners, and in this case, they have been very large.

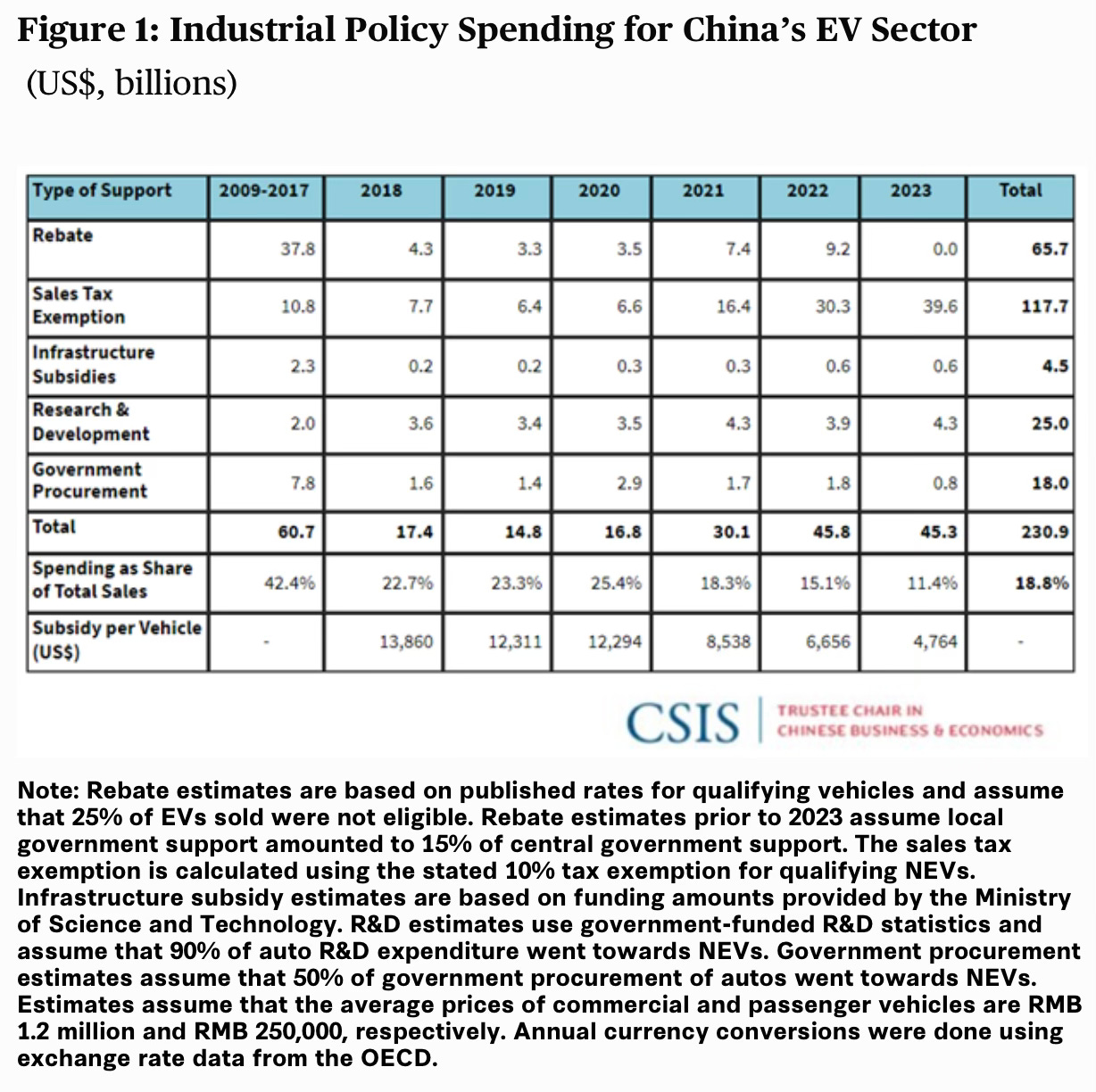

A study by CSIS estimates that Chinese EV makers have received a staggering $230 bn in subsidies since 2009. Subsidies have nearly tripled during 2018-20 and have risen sharply since 2021.

The composition of subsidies has changed over time from sales price rebates in the early years to sales tax exemption now as the industry has matured.

In this context, Dani Rodrik proposes a beggar-thy-neighbour test for a distortionary industrial policy, which appears to exclude Chinese-like industrial policies that support renewable and other new technologies. He writes,

When the Chinese government subsidizes research and development that enhances the country’s competitiveness in high-tech products and lowers their prices on global markets, the US and other advanced economies are hurt, because these are the areas of their comparative advantage. Despite the harm, however, we would not consider it proper to ask China to remove such subsidies, because our intuition tells us that supporting R&D is a legitimate tool to promote economic growth, even if others incur losses… Applying this perspective to the real world, one finds that the bulk of industrial policies in China and the US today are not beggar-thy-neighbor. In fact, many should be considered enrich-thy-neighbor.

The clearest example is the broad range of green industrial policies that China has deployed over the last couple of decades to bring down the price of solar and wind power, batteries, and electric vehicles. These policies have been doubly beneficial to the world economy. They generate innovation spillovers, reducing costs for the world’s producers and lowering prices for consumers. And they accelerate the transition from fossil fuels to renewables, partly compensating for the absence of carbon pricing. When industrial policies appropriately target externalities and market failures – as in the case of green subsidies – they are not something to worry about. Moreover, while we can raise legitimate concerns about cases where these conditions are not met, the fact remains that the costs of inefficient industrial policies are borne primarily at home. It is domestic taxpayers and consumers who pay in the form of higher taxes and prices. Bad industrial policies are less beggar-thy-neighbor than beggar thyself…

Trade partners are always free to impose their own safeguards, even when the policies they are responding to are not beggar-thy-neighbor. For example, if a government is worried about national security or adverse consequences for local labor markets, it should have the freedom to introduce export restrictions or tariffs to address these concerns. Ideally, such responses will be well-calibrated and targeted narrowly at the stated domestic goal, rather than being designed to punish countries that are not engaged in beggar-thy-neighbor policies. Distinguishing the small number of beggar-thy-neighbor actions from the vast array of other policies with cross-border spillovers is an important first step to easing trade tensions.

I think Dani Rodrik gets it wrong here in the context of China’s policies on renewable and other cutting-edge technologies. While China’s industrial policies in these areas might have created spillovers and helped hasten the green transition, they have also had damaging consequences for industries and economies.

Across sectors from textiles and footwear, consumer electronics, thermal boiler-turbine-generator (BTG), metro railways, solar panels, cars (ICE and EVs), EV batteries, etc., China has employed the same set of policies over the last three decades. They consist of building massive capacity on the back of heavy industrial policy subsidies (in addition to low-cost land, electricity, and credit) and dumping excess capacity abroad at discounted prices, thereby rendering the importing country firms uncompetitive and capturing those markets.

In addition to direct subsidies, Chinese manufacturers benefit from similarly subsidised component makers and their competitive discounted pricing, and a willingness or ability to produce and expand regardless of profitability (despite their global dominance, very few Chinese EV makers are profitable). For all these reasons, foreign competitors face a heavily tilted playing field when facing Chinese car makers. These policies have decimated industrial bases across trade partners, and caused tens of millions of job losses.

These economic impacts alone would have been sufficient to initiate protectionist measures against Chinese imports. But compounding matters, the country’s clearly aggressive foreign policy intentions and willingness to weaponise its manufacturing dominance pose national security risks that necessitate strict policies to protect the domestic economy against Chinese imports. Given these motivations, it’s inevitable that any market dominance becomes detrimental to the interests of other countries. The only way to counter it is by restricting market access to Chinese exports.

No comments:

Post a Comment