Some graphics from a very informative report by real estate consultancy Knight Frank on Indian infrastructure.

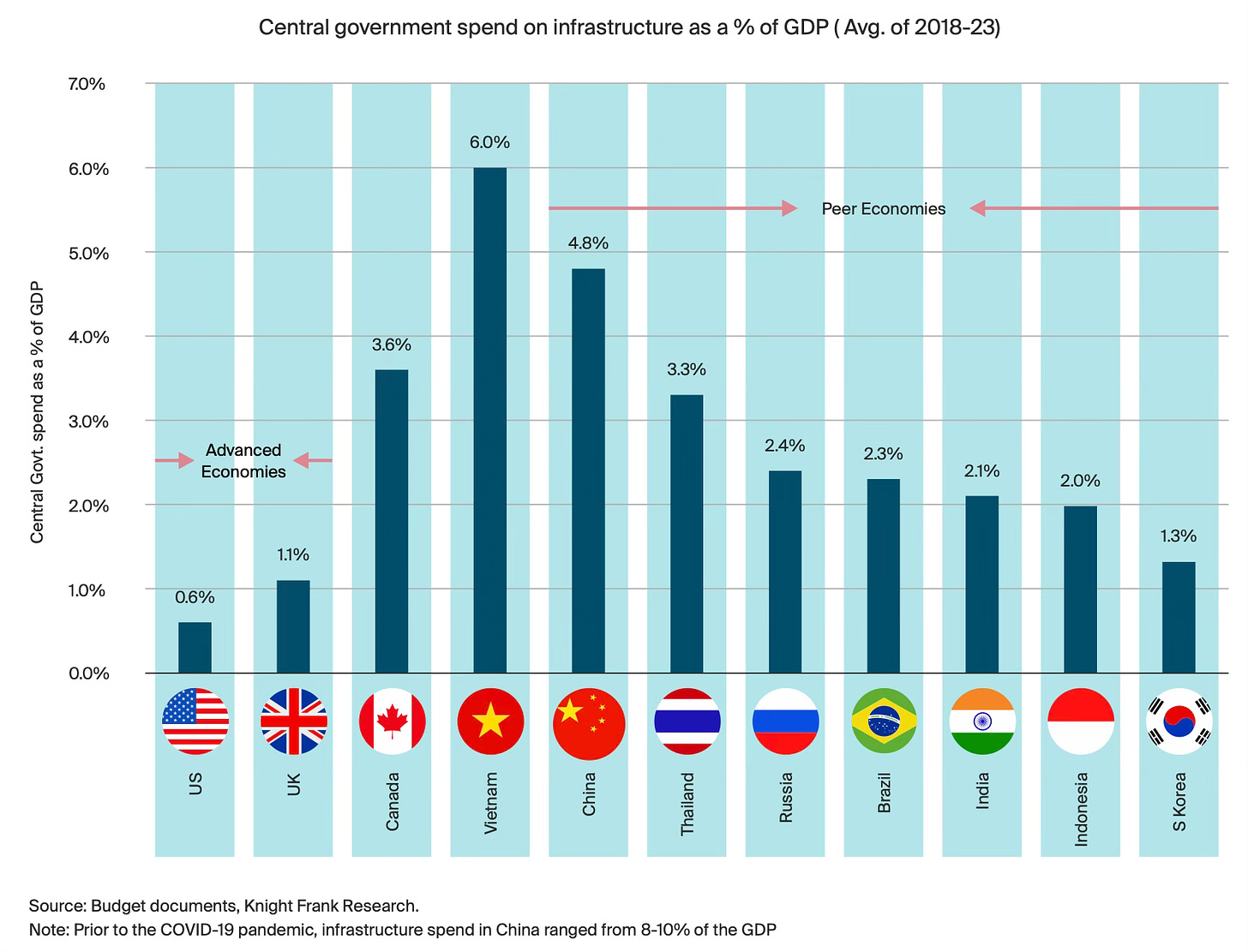

India spends less on infrastructure than other major economies.

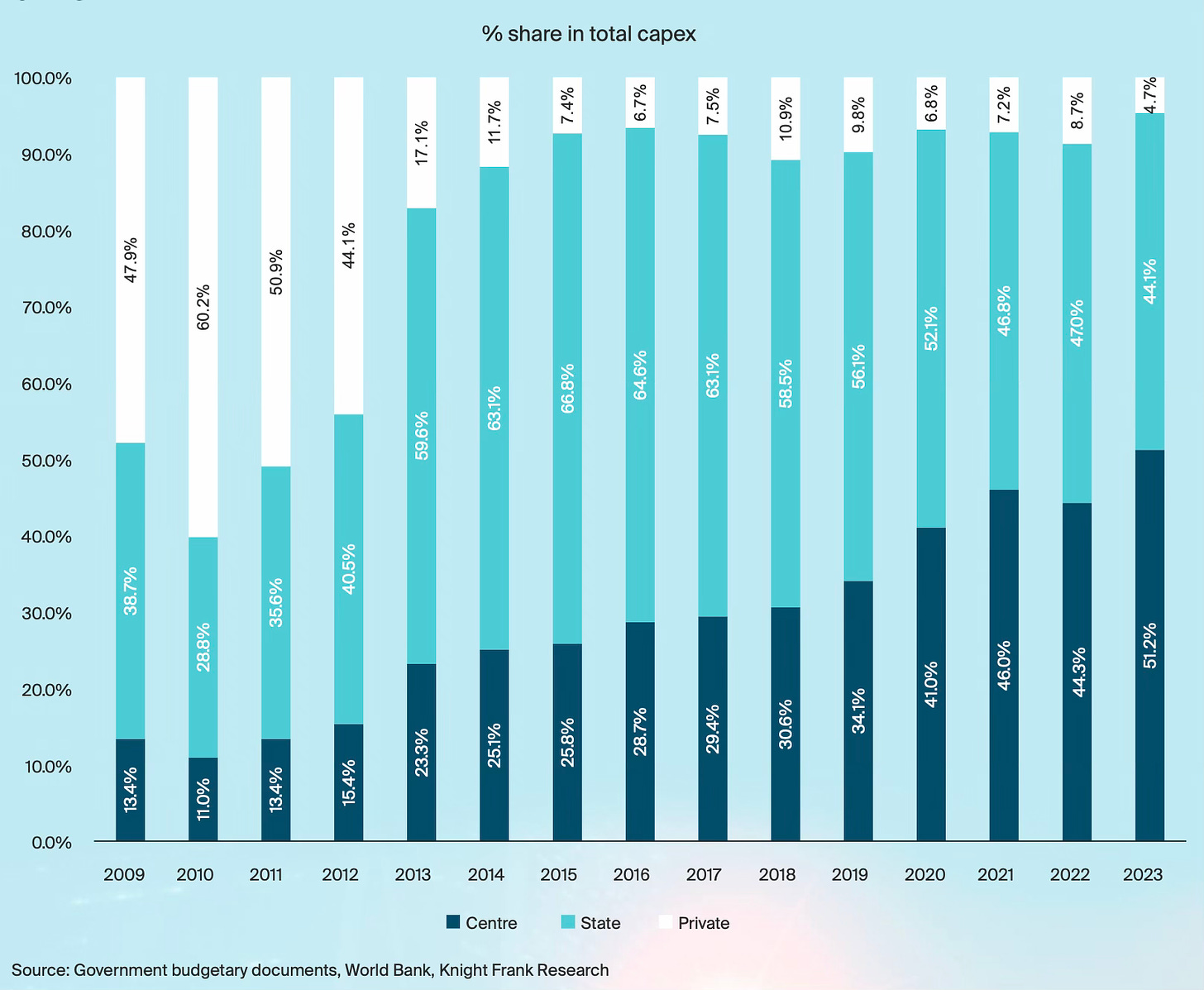

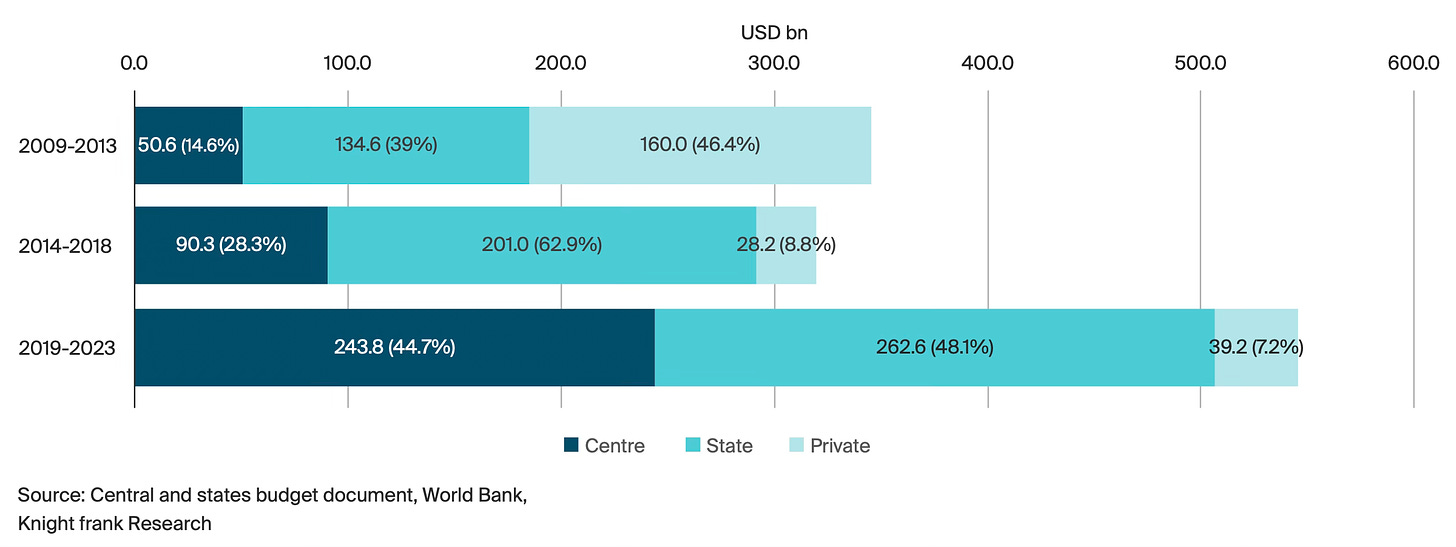

A disturbing feature of India’s infrastructure finance landscape over the last decade and a half has been the decline of private finance and the dominance of public finance.

In absolute terms, over the last three four-year periods, private investments have declined by three-fourths in the four years ending 2003, even as central government public investments have risen five-fold. Total public investments rose from $185 bn to $505 bn. Private investments contributed just 7.2% of all infrastructure investments in the 2019-23 period.

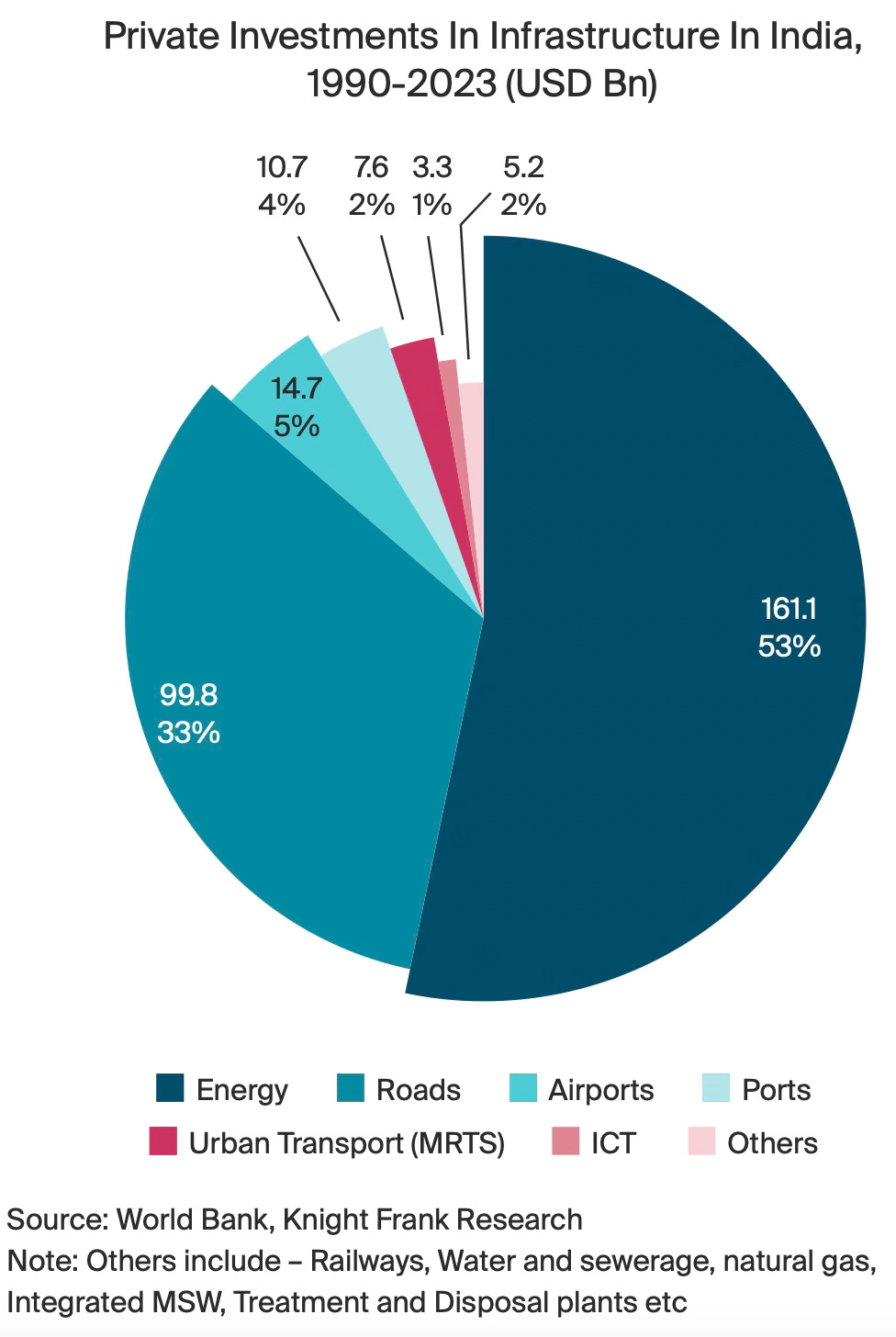

In the 1990-2023 period, private investments amounted to $305 bn, most of which going to energy and roads. Along with ports and airports, they have formed 95% of all investments in this period.

Interestingly, in this period, urban transport projects attracted $7.6 bn, water supply and sanitation $1.6 bn, and waste management $1.3 bn of private investments. Railways attracted a mere $0.02 bn in private private investments.

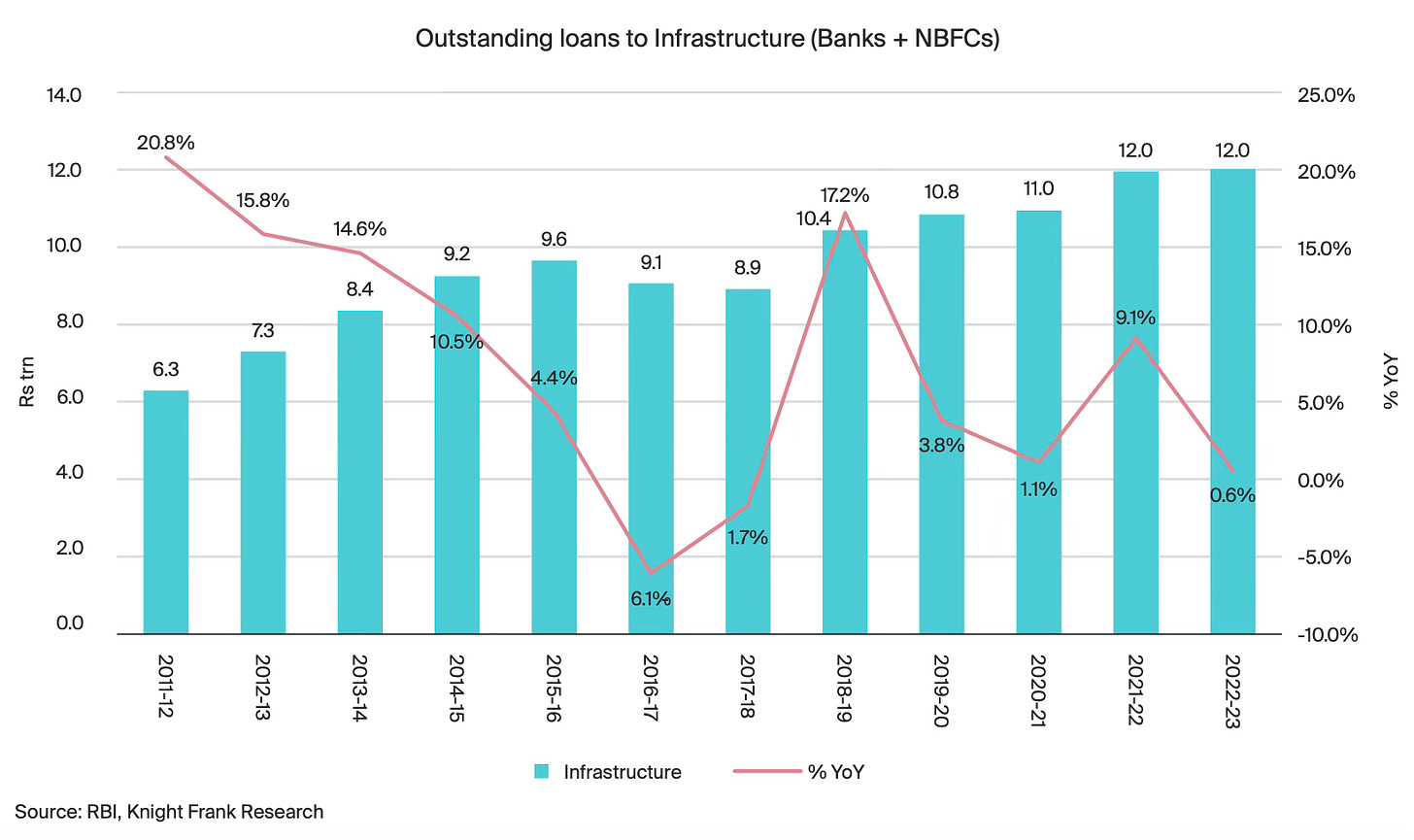

Banks and NBFCs, the major source of infrastructure debt finance for private investors, has plateaued since 2018-19 (or has grown little since 2014-15). The total outstanding loans to infrastructure sector has risen by just Rs 2.8 trillion since 2014-15, an annual growth rate of 3.38%.

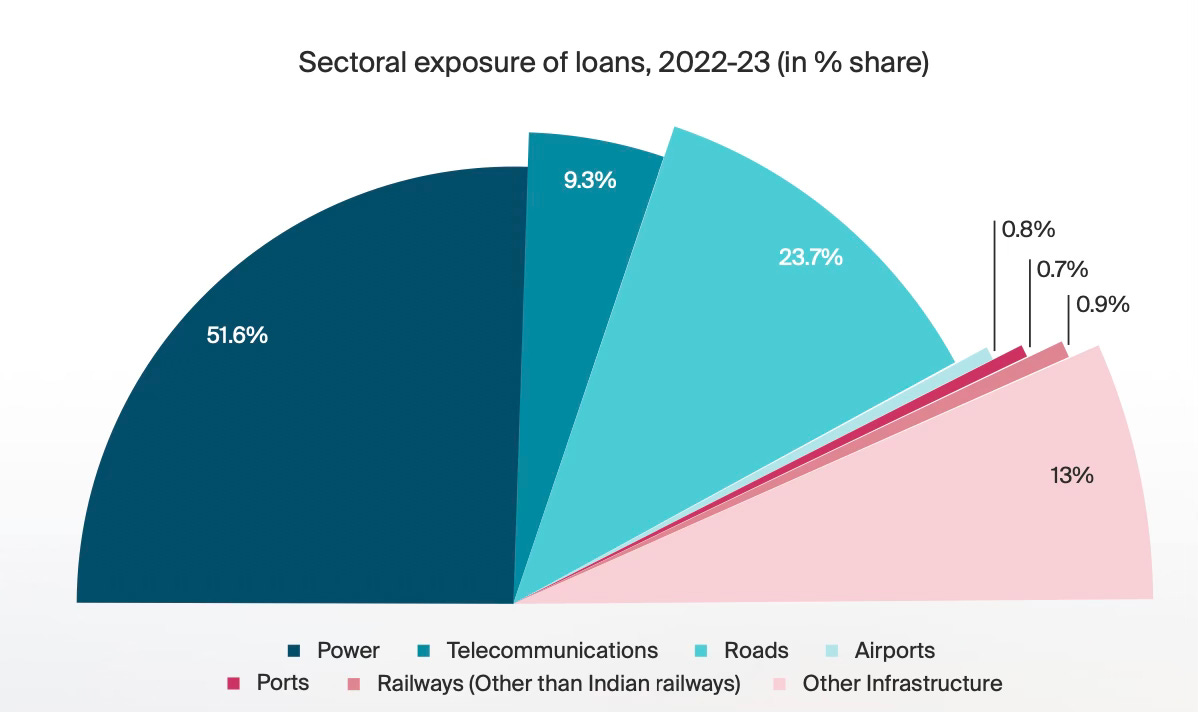

Again, mirroring private investments in general, power, telecommunications, and roads made up 85% of all loans.

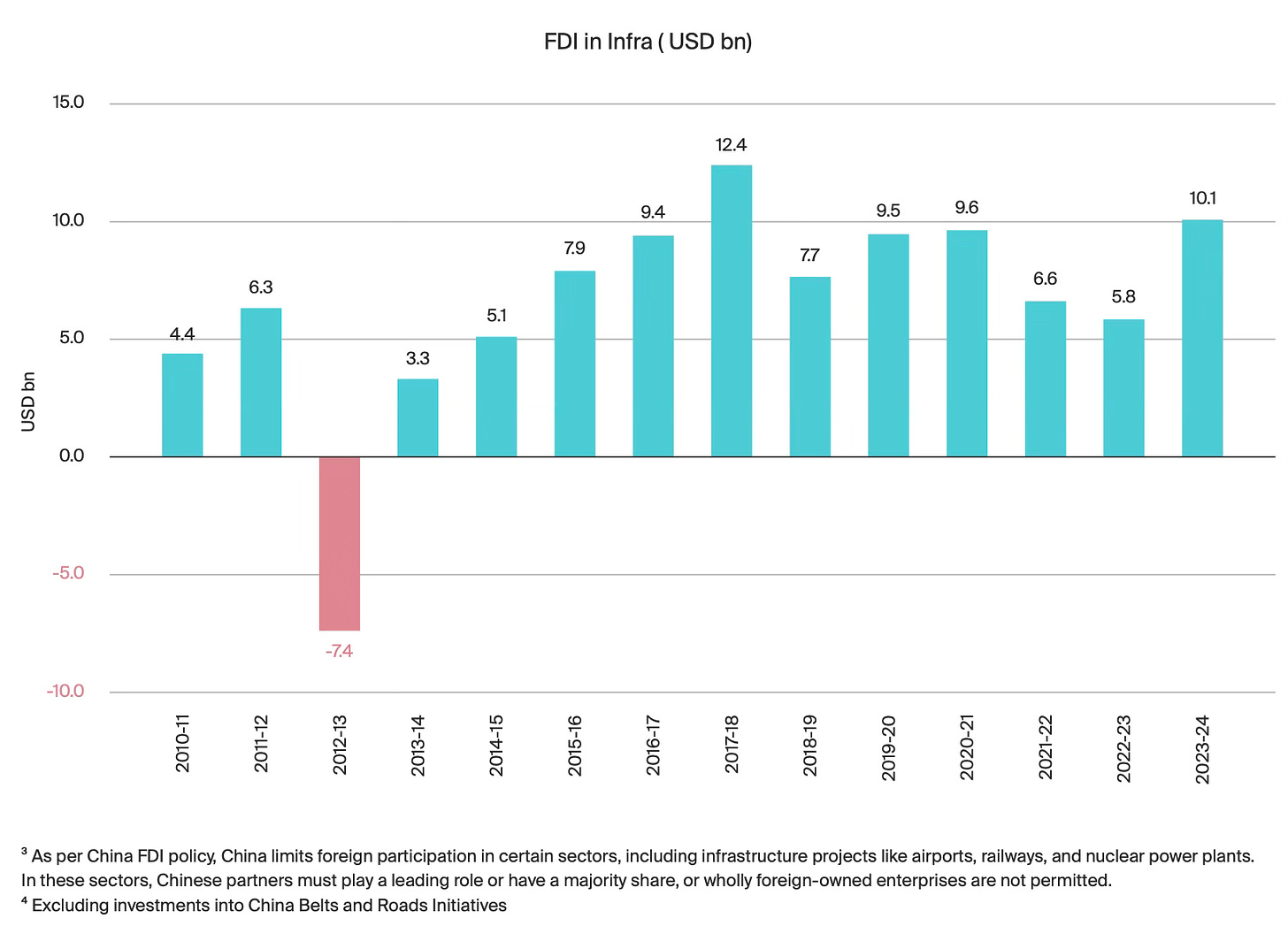

FDI has been in the range of 0.15-0.25% of GDP, compared to the central government spending of 2.5-3% of GDP and total public spending on infrastructure of 5-6% of GDP.

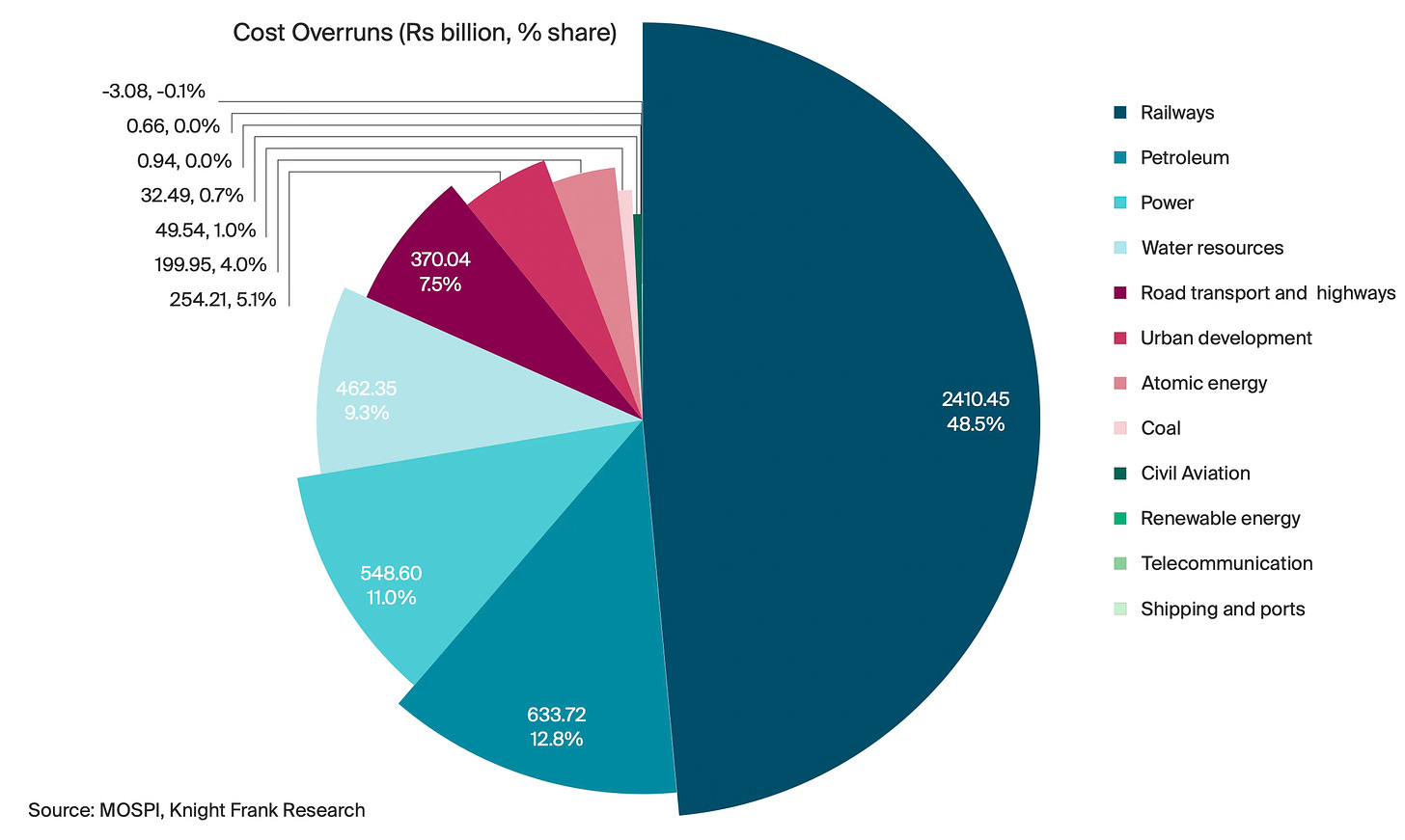

Railway projects formed nearly half by value of all cost overruns.

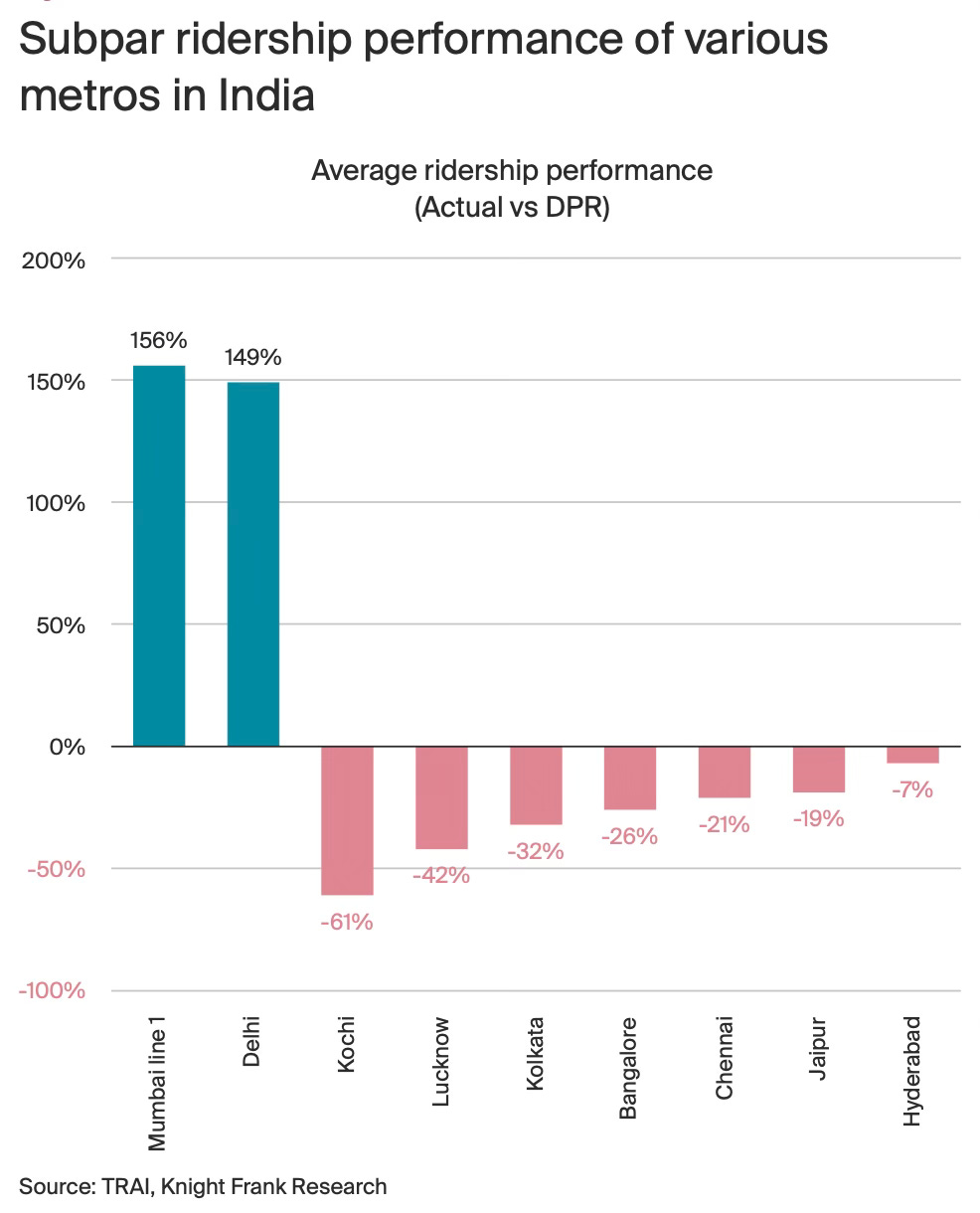

Underlining the point about strategic misrepresentation in traffic estimates of metro rail projects, actual ridership has fallen short of estimates in all cities except Mumbai and Delhi.

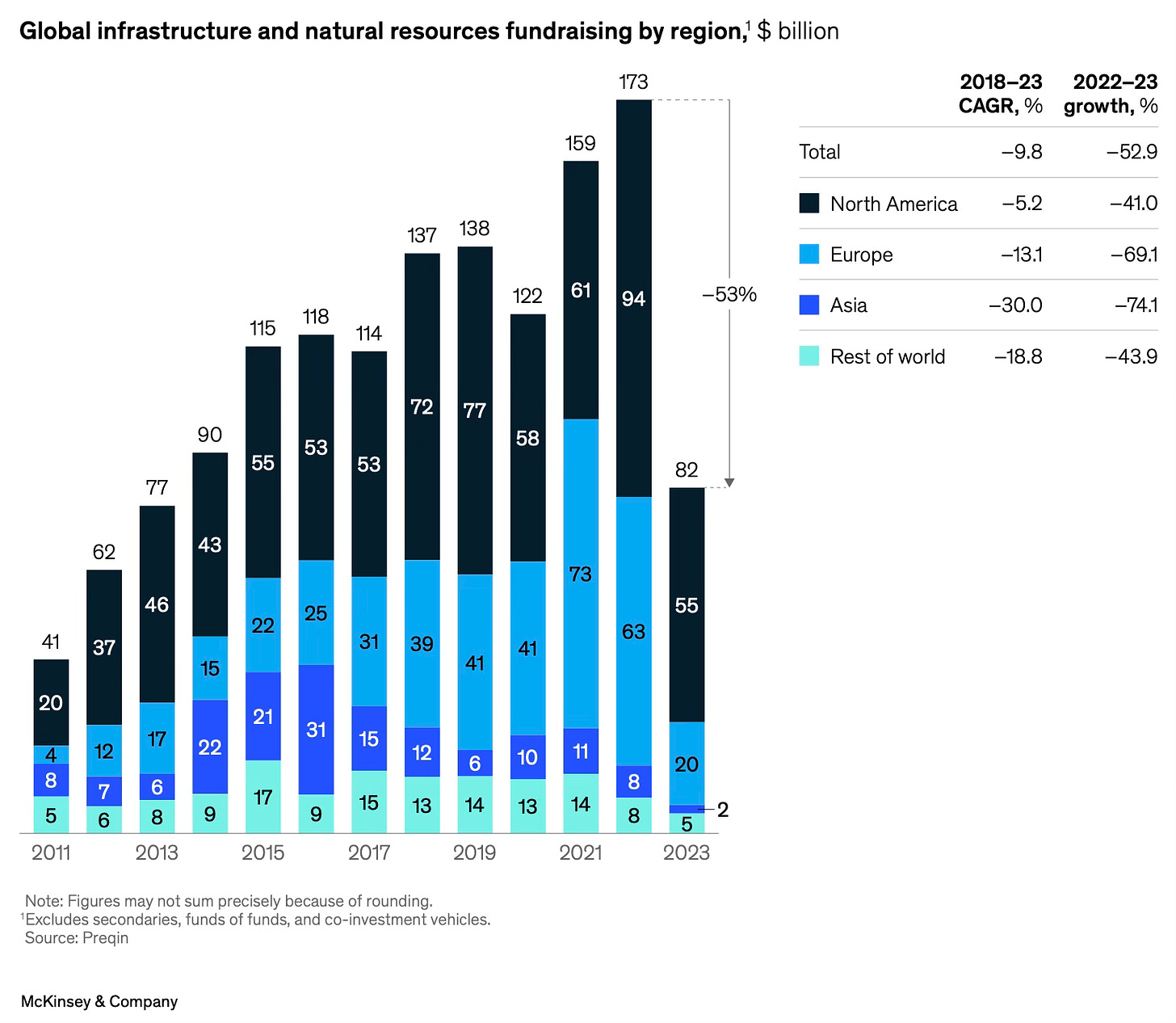

Finally, the point about FDI is underlined by this graphic from a McKinsey report. The total Asia-focused private capital flowing into infrastructure and natural resources is less than $10 bn and declining.

Against this backdrop, here are some observations.

1. At the behest of experts and multilateral institutions, the efforts of central and state governments in the mobilisation of infrastructure finance have hitherto been focused on bond market financing. As I have blogged multiple times, this is a misguided endeavour. Capital market financing of projects in even de-risked sectors will always remain a small proportion.

Instead, policy attention should focus on expanding the coverage of bank finance for revenue-generating projects in those sectors with limited private participation and debt exposure. There’s a need for concerted efforts in this direction, like the decades-long policy campaign to deepen municipal bond markets in India.

2. The debt exposure of infrastructure sectors like railways, urban mass transit, water and sewerage, solid waste management, electricity distribution etc., is negligible. As I blogged here, commercial debt formed just 2% of all urban infrastructure finance. This points to a valuable opportunity (albeit very less discussed) to leverage debt finance to fund projects in these sectors.

But there are deep ideological and daunting political economy challenges that must be overcome to capitalise on this opportunity and leverage debt finance.

All these sectors are also those where private capital is unlikely, and most of these investments must come from public finance. Since these sectors generate some revenue, even if not enough to cover the capex, there’s a strong case for blending public finance with debt capital. This will also expand the shelf of projects that can be funded with scarce public finance.

There are at least two arguments against blending publicly financed projects with debt. One, debt finance comes with a cost of capital, whereas public finance is a grant. Even if debt is to be mobilised, it’s cheaper for governments to borrow directly and fund these projects from the budget instead of allowing the project entity to raise project finance. However, there are limits to direct public borrowings.

Two, borrowings by public entities have the potential to generate perverse incentives arising from the political economy. The disturbing rise in government-guaranteed debts assumed by state government public sector enterprises points to this concern. Finance Departments are therefore averse to allowing public entities to raise debt.

Addressing these concerns requires attention on both supply and demand sides.

On the supply side, it’s required to create confidence among banks and NBFCs to lend to such projects. Given the political economy associated with tariffs and user fees, lenders prefer to stay away from such projects. Asset-liability mismatches from bank lending should be minimised through the likes of loan syndication and takeout financing.

On the demand side, one strategy is a proposal outlined here on allowing government entities to create Special Purpose Vehicles (SPVs) that could raise project debt against the project revenue streams. This structure would align incentives and address the political economy distortions. In the initial years, lenders could be de-risked through a guarantee fund mechanism that would provide them partial guarantees.

To support this, the Government of India should restrict grant funding in these sectors only to the extent required to meet the viability gap that would allow the project entity to raise debt. This would also allow the government to prioritise scarce public finance to those areas where private capital or debt cannot be mobilised. The GoI’s Viability Gap Funding (VGF) scheme should prioritise public-funded projects in these sectors that utilise debt.

3. Public policy engagement on private participation in infrastructure should no longer be about sectors like power generation and transmission, highway roads, airports and ports. These are largely de-risked sectors in India, except for certain remote areas where their project’s commercial viability is questionable.

Instead, the policy focus should be to attract private capital towards electricity distribution, railways, fishing harbours, and the large segment of urban infrastructure services - water supply, sewerage, street lighting, solid waste management, mass transit (buses and metro rail), parking facilities etc.

For a start, the current levels of private participation in these areas is minimal, and given the difficult political economy of tariffs and user fees, there’s a need to de-risk them for private investors. More importantly, projects in these sectors require varying levels of VGF to cover the upfront investments. Therefore, public funding for infrastructure should prioritise these areas. A part of the GoI’s 50-year interest-free capex loans to state governments could be allotted for such financing (to meet the state government's share of the VGF funding).

No comments:

Post a Comment