Arguably one of the biggest constraints to sustained high economic growth rates in India is the low female labour force participation rate. Much has been written on the topic, analysing the possible causes and proposing solutions.

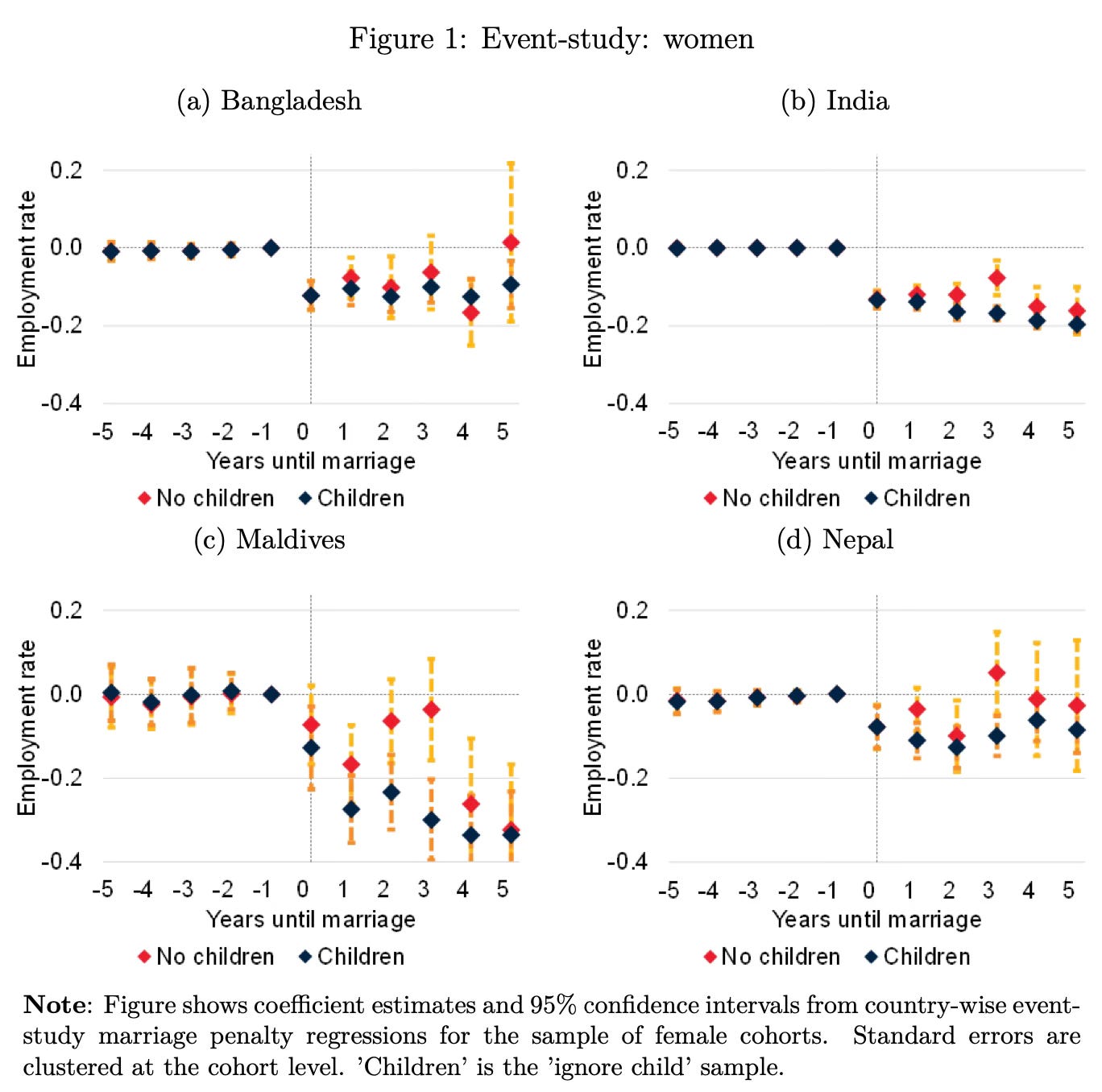

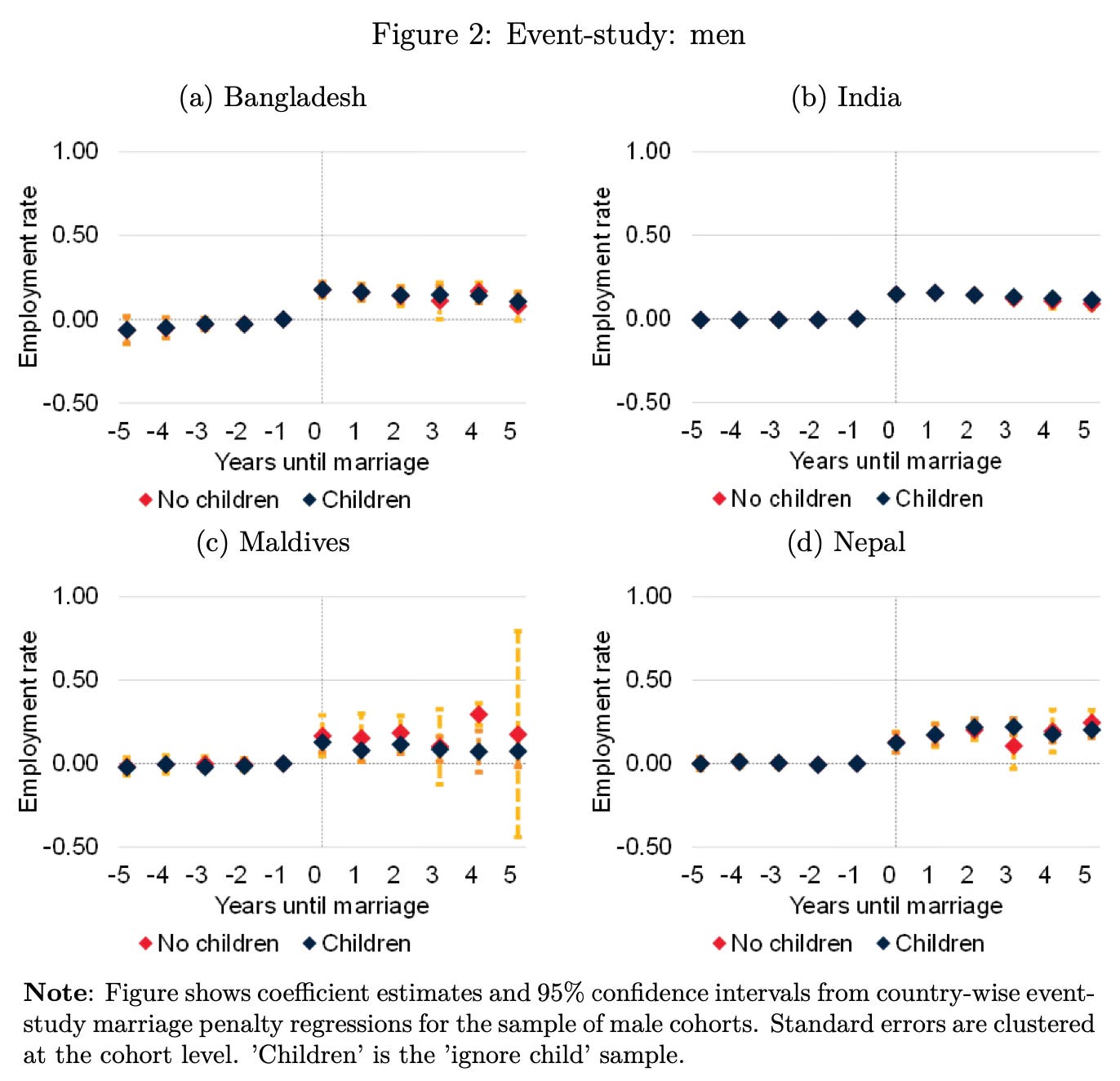

A new World Bank working paper by Maurizio Bussolo, Jonah Rexer, and Margaret Triyana points to a marriage penalty. This penalty forces women to drop out of the labour force post-marriage. They used statistical techniques on data from multiple rounds of the nationally representative Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) from Bangladesh, India, Maldives, and Nepal and isolated the marriage and child penalties for women. They find that the penalty is highest in India.

These two events are correlated in time for a given individual. As such, estimates of the marriage penalty are obscured by the presence of children, and estimates of the child penalty are likewise capturing at least in part a marriage penalty… We find that South Asian women reduce their labor force participation by 12 percentage points (p.p.) following marriage, even before childbearing. Among women with children, this rises just 4 p.p to 16 p.p. As such, 75 percent of the combined family formation penalty is driven by marriage itself, rather than the burden of childbearing, at least in the first five years of marriage.

The largest effects are observed in India, while more muted effects are observed in Nepal, where the majority of the combined penalty is driven by children. Dynamic event-study estimates reveal flat trends in employment status leading up to the marriage date, and sharp drops in employment in the first year of marriage. These trends lend additional support to the notion that these estimates represent the causal effect of marriage. Men, in contrast, enjoy a marriage premium. This premium does not depend on the presence of children, consistent with the existing literature showing no child penalties for men… We find that educated women have much smaller marriage penalties, with post-secondary education erasing nearly half the baseline marriage penalty.

They examine the possible causes

The marriage penalty may represent an optimal solution to a joint household maximization problem. If women have limited outside options in the labor market relative to their husbands, then specialization in home-based tasks might be economically efficient, even without children. However, the value of women’s home production is greatly diminished without children, suggesting a role for social norms in driving the marriage penalty, particularly those that constrain women’s mobility outside the home… Despite the fact that gender norms are more progressive in urban areas in South Asia, we find no significant difference between urban and rural marriage penalties… we argue that a woman’s education affects both household gender norms and her outside employment options. In contrast, her husband’s education affects household norms, but does not directly affect her employment prospects. This suggests that outside options at least in part play a role in determining the marriage penalty… We find strong evidence that women in households with more liberal gender norms experience smaller marriage penalties. The effects of education and social norms appear to be independent, suggesting that both opportunity costs and social norms play a role in driving the marriage penalty.

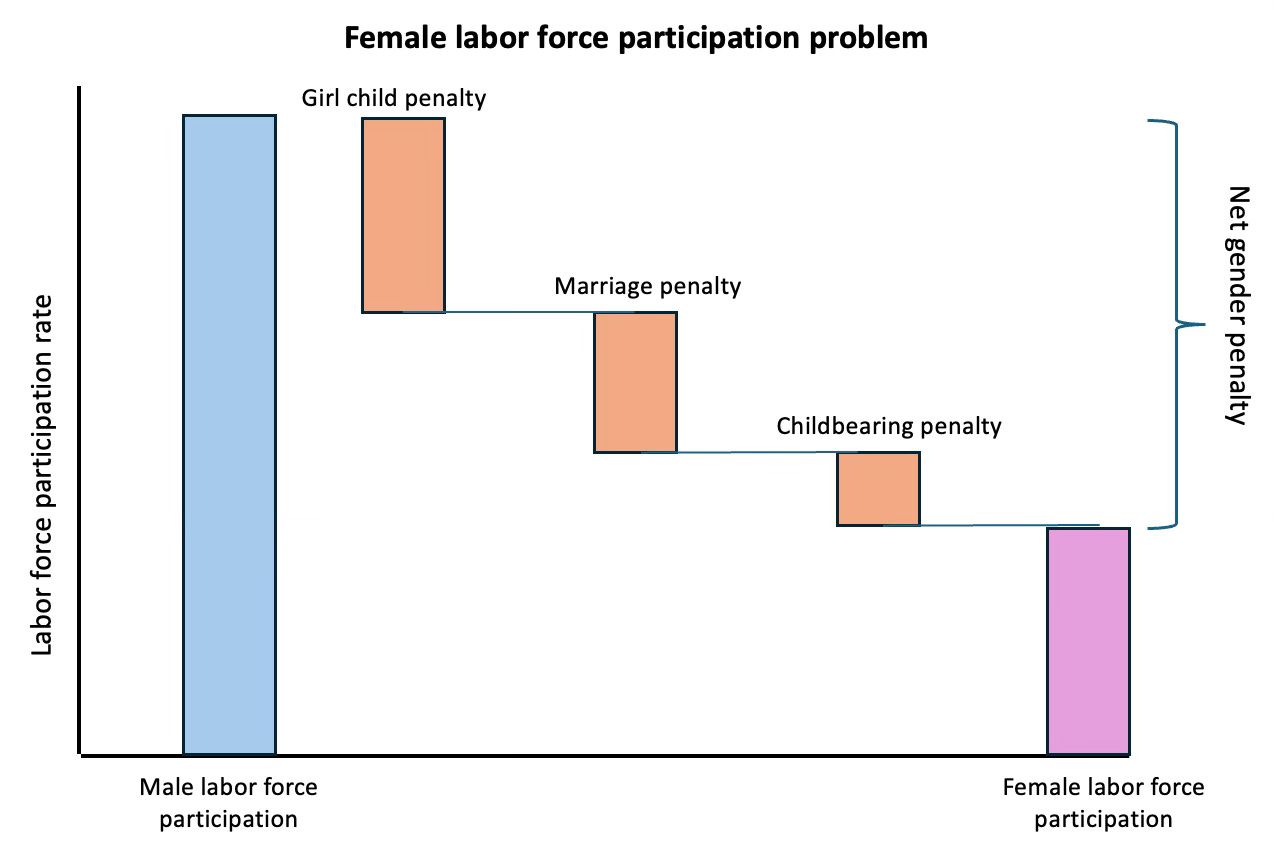

As a framework, the net penalty on female labour force participation can be considered as a cumulative result of three effects, as captured below.

The marriage penalty is clearly higher in India compared to even its South Asian counterparts like Nepal and Bangladesh, pointing to historical and cultural factors. When faced with such entrenched legacies, public policy might be able to only do so much. Measures like establishing creches at workplaces or providing free bus passes might at best be tinkering at the margins.

Even a significant increase in access to girl children’s school education might not be sufficient to overcome these penalties. This possibly explains the lack of meaningful improvements in the female labour force participation rate in India despite the considerable improvements in girl’s school enrollment and retention rates.

Meaningful change in the status quo will require changes in cultural (within the family) and social (in society) norms and sharply increasing access to higher education for girls and good jobs.

Higher education can enable women to get higher-paying and higher-status jobs and, over time, increase their now negligible proportion in senior management levels in public and private sectors. This kind of economic mobility/status, with several examples of aspirational models across small communities, might be required to have a significant impact on cultural and social norms. The factory-floor jobs in manufacturing, while very important, are more likely to take the long route to change in revising cultural and social norms.

Public policy should pursue ways to increase access to higher education for female students - scholarships, preferential policies in admissions etc. Simultaneously, the private sector needs to become sensitive to increasing the share of women in senior management positions.

No comments:

Post a Comment