This is the latest in the series on the Chinese economy - here, here, here, and here. See also this and this.

Four aspects of China’s economy should be of big concern—low household consumption expenditures co-existing with a high savings rate, excessive reliance on investments to drive growth, low bang for the buck from its high investment rate, and a debt overhang that threatens the finances of its subnational governments and corporations. While they have been concerns for some time, the combined effect of all three is now a binding constraint on economic growth. Addressing them is critical to the country’s long-term prospects.

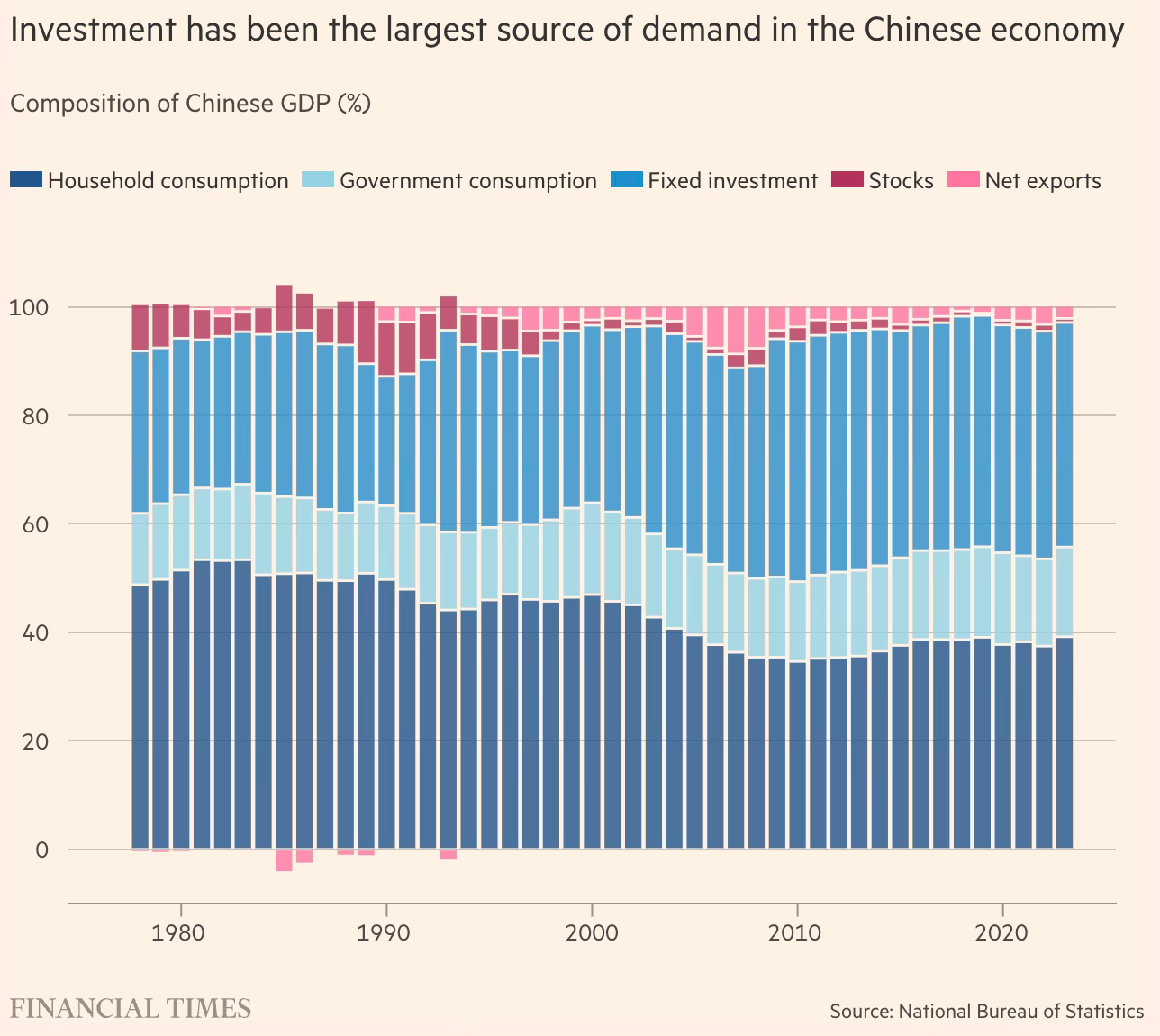

In an economy, aggregate demand reflected in consumption leads to investment and job creation, which fuels further demand in a self-reinforcing cycle. While government consumption too creates demand, household consumption is the primary driver of economic growth. China’s domestic consumption has remained unusually low even when compared to other developing countries and remarkably, has steadily fallen from 53.38% of GDP in 1984 to 46.96% in 2000 to 37.46% in 2022. Its share ranges from 60-70% for most countries, including India.

This economic structural problem of low and declining base of household consumption has been the biggest challenge for the Chinese government in its pursuit of sustaining high growth rates. As we shall see, a confluence of other problems that have become more acute is making it a binding constraint.

For a government which has historically tightly managed the economy and shown a willingness to step in at the slightest sign of distress, Beijing, especially under Xi Jinping, has shown a surprising reluctance to support household consumption. To be fair, historically Chinese governments have preferred to intervene on the supply side. It has resisted demand-side interventions like expanding affordable access to services like healthcare and education (one reason for the propensity for large savings), leave aside any fiscal stimulus.

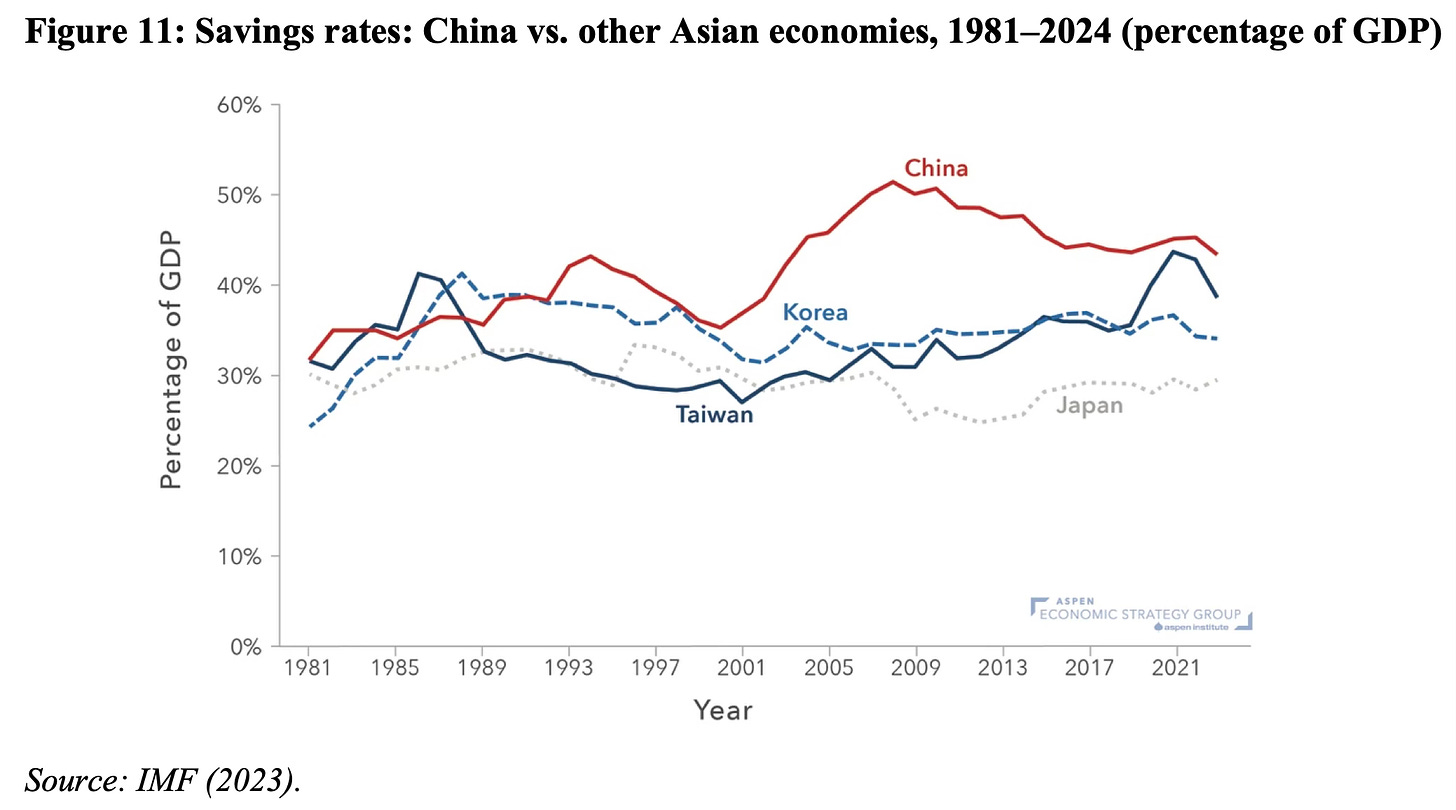

The low consumption has co-existed with very high household savings, which finds its way into supporting the country’s high investment rates. The persistent high savings must find an outlet within the economy or outside.

It’s the source of at least two important distortions in the economy. One, for a long time, the real estate sector absorbed a significant part of the savings. But once it started floundering and with domestic consumption weak, it became inevitable that the surplus find its way out as external surpluses from the surge in exports. Two, the high level of savings fuels a repressive financial system, where it gets directed to the government’s prioritised sectors and sustains a distorted investment-driven economic growth model.

It’s been remarkable that all through its high growth decades, especially since the turn of the millennium, Chinese households have preferred to increase their accumulation of savings and reduce their relative share of consumption. This propensity to double down on savings and avoid spending speaks of economic insecurity.

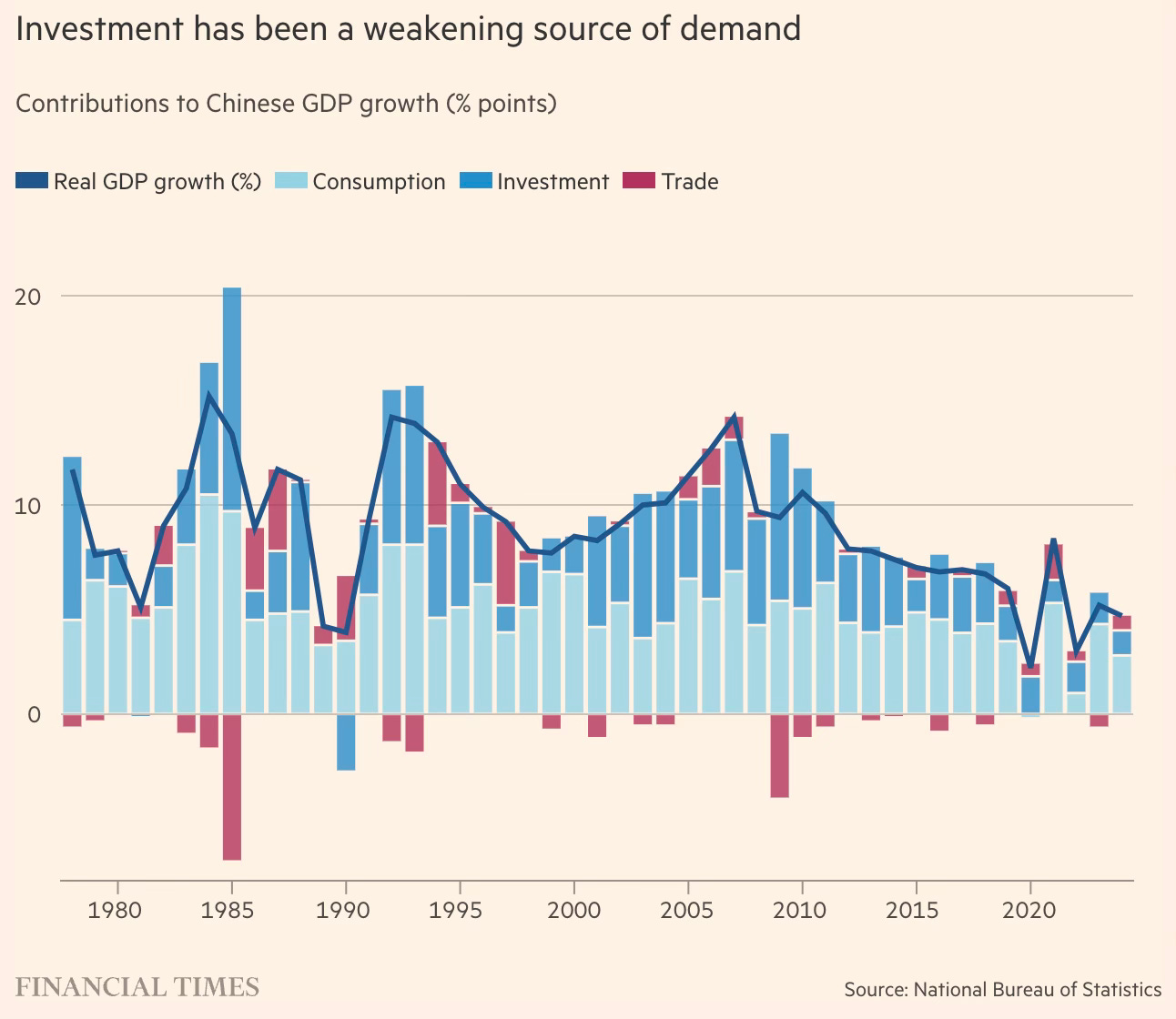

With the standard driver of economic growth out of the equation, the government has no option but to rely on investments to drive economic growth. This creates the challenge of figuring out the sectors to funnel credit and drive investment. Here the Chinese industrial policy has consistently targeted sectors for government support.

For long, perhaps the longest period of its high growth era, export-driven manufacturing and infrastructure investments have been the government’s primary drivers of economic growth. The former served the export markets and made China the factory of the world. Once domestic infrastructure demand plateaued, real estate, which was always an important source of growth, became the government’s preferred destination for credit. It was supplemented with the export of domestic excess capacity into building out the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). But by about 2020, the authorities had come to realise the perils of the real estate bubble and had started introducing measures like the “three red lines” to cool the real estate market. The property market defaults were to duly follow.

Beijing’s latest preferred investment destinations have been green technologies like solar panels, electric vehicles, and batteries, critical technologies like semiconductor chips, and critical minerals like lithium. It has channelled fiscal incentives and credit to these industries, and these investments have propped up economic growth. This focus is in line with President Xi’s stated objective of unleashing “new quality productive forces” and achieving self-sufficiency in frontier technologies.

The problems with this investment-based economic growth strategy were papered over during the years of high growth. But once the economy began weakening after 2018, its limitations came to the fore.

Thanks to the long years of investment-driven growth, the country is awash with massive overcapacity across sectors. In sectors like steel, solar, and internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles, the Chinese production capacity is often comparable to or higher than the rest of the world put together. Worsening matters, domestic demand has plateaued or is declining. The excess capacity has no outlet except exports. Accordingly, Chinese firms compete to dump their produce in export markets, forcing the inevitable backlash and protectionism in those countries.

This backlash is no longer confined to the US and Europe, but is rising even among China’s developing country partners. Factory closures and job losses due to cheap Chinese imports have become a uniform source of discontent and anger across countries. The cheap Chinese imports are one of the biggest problems facing the world economy today.

The combination of weakening domestic demand, corporate indebtedness, and protectionism among trade partners is exposing the limits to such an investment-driven strategy.

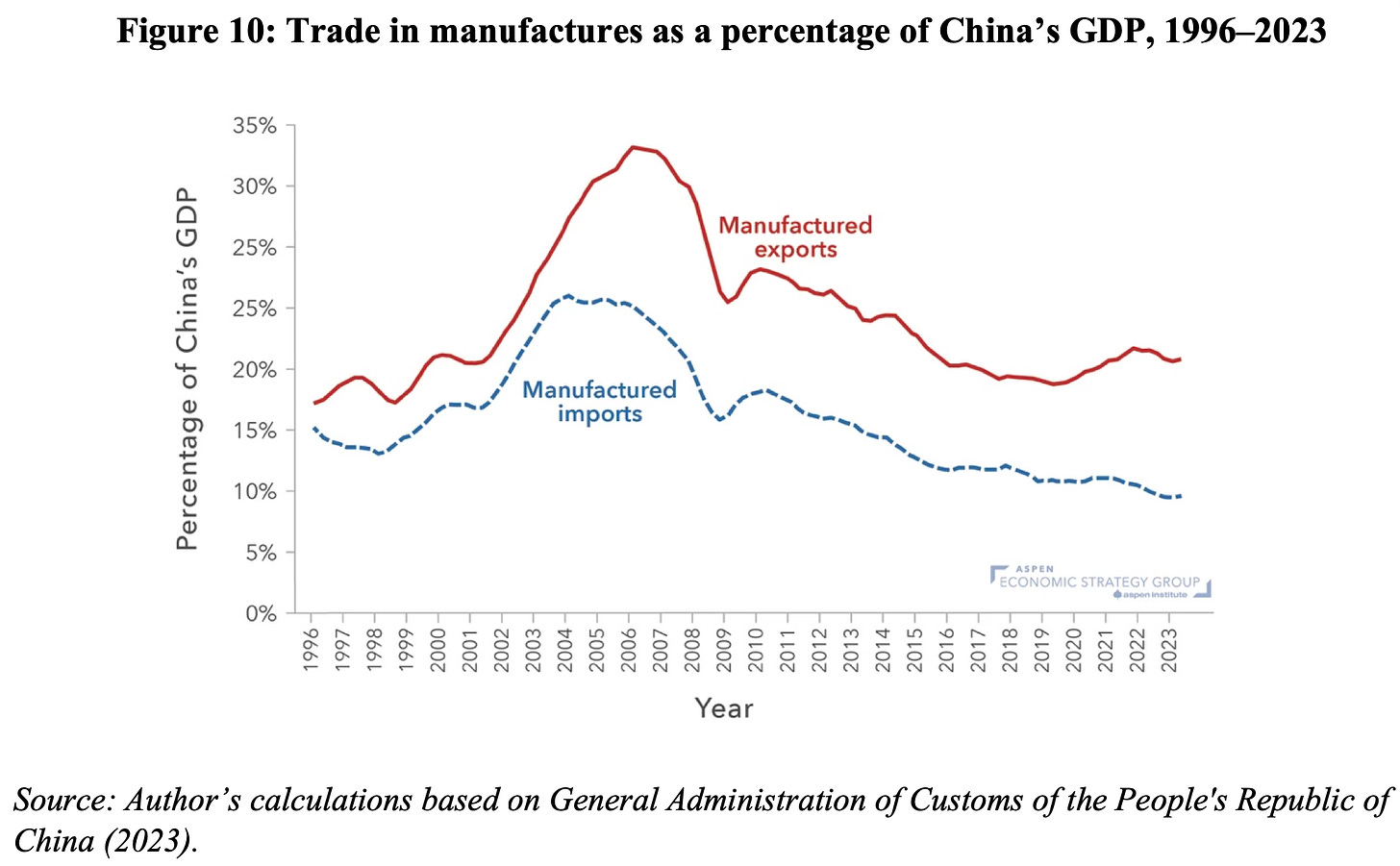

In this context, Brad Setser points to an important observation about the Chinese economy. He shows that for over a decade since the global financial crisis, Chinese exports and imports grew slower than its GDP growth rate, thereby driving down the share of exports to GDP. He argues that the de-globalisation observed in this period was driven by this trend.

However, since 2019, there has been a surge in Chinese exports and its surplus in manufactured goods “has increased by about three-quarters of a percentage point of world GDP and is now at a record high.” In the last four years, its exports have surged by nearly a trillion dollars. This re-globalisation of the Chinese economy has coincided with its real estate troubles and plateauing of domestic demand.

The surge in Chinese exports has been driven primarily by green technologies, critical minerals, and electric vehicles and their batteries. They have made entire supply chains critically dependent on China. Supply chain diversification by way of shifting of assembly to the likes of South East Asia, Mexico, and India, does not address the underlying exposure to component imports from China. The export focus to prop up a weakening economy also led to a sharp rise in exports to other developing countries. This more than offset the relative slowdown in exports to the advanced countries.

It can be argued that the de-globalisation was driven by the demand generated by a fast-growing economy and associated domestic absorption of the country’s rising production capacity across sectors. On the same lines, the current re-globalisation has coincided with the weakening of economic growth and aggregate demand. It has created an imperative to backstop further declines by exporting the massive economy-wide excess capacity accumulated during the high growth years.

Setser has a good summary

These data points highlight the surprising conclusion that, in years after the pandemic and after the imposition of Trump’s tariffs, China’s economy has become more integrated, not less integrated, into the structure of global trade. The recent surge in China’s exports and in its trade surplus stems primarily from China’s sharp domestic slowdown and its still-unresolved property market crisis. China’s internal demand growth has faltered, and it has instead relied again on exports and global demand to support its growth. This form of globalization is unhealthy to be sure, as it stems from unresolved imbalances inside China’s economy, but it is nonetheless globalization.

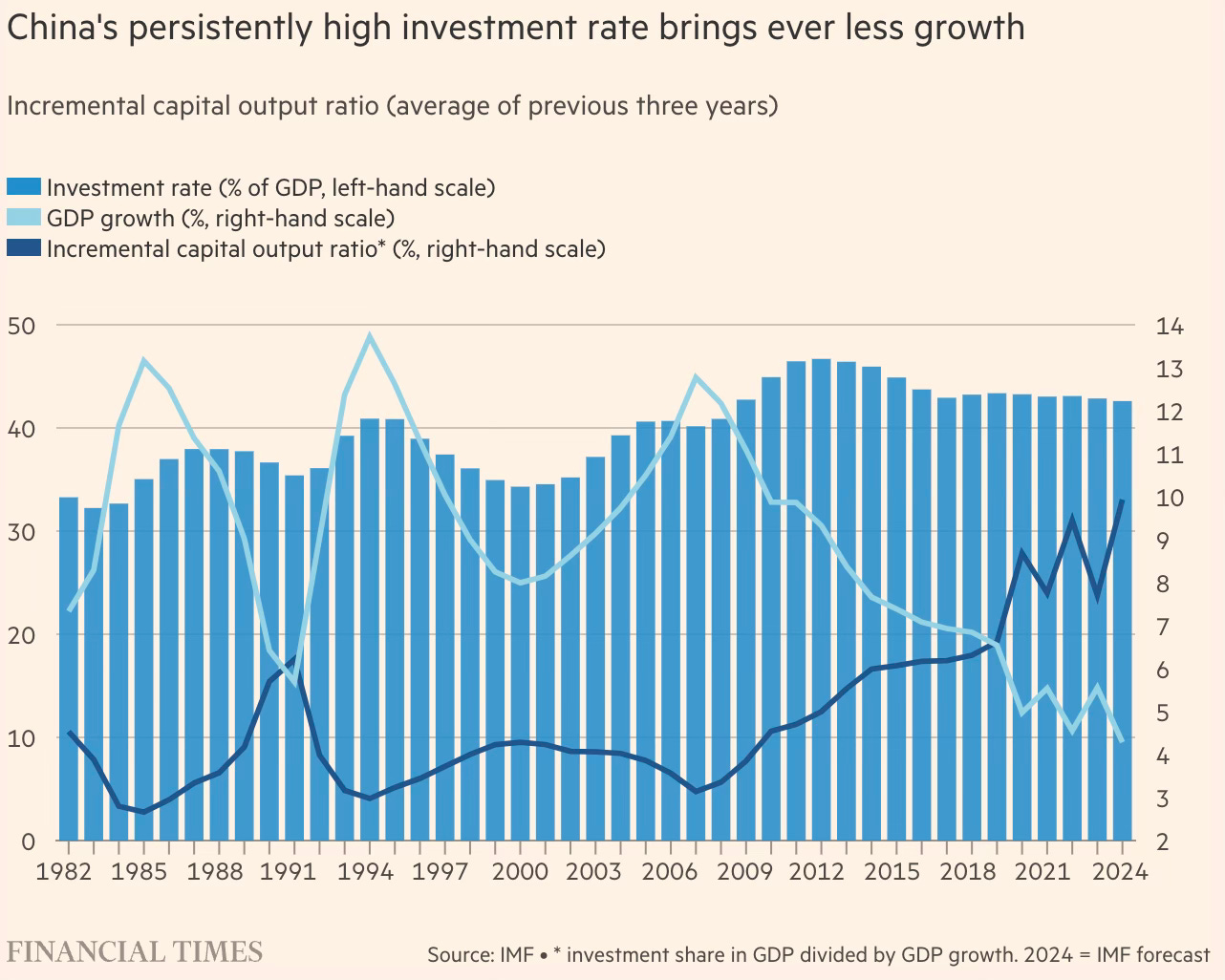

This brings us to the third problem. As the government has pursued a predominantly investment-driven growth model, the bang for the buck from every additional renminbi of investment has diminished considerably. This is reflected in the sharply rising incremental capital output ratio (ICOR). Even as investment has been range-bound at 43-45% of GDP since before the global financial crisis, the ICOR has nearly trebled from below 3.5 to touch 10. This period has also coincided with economic growth declining precipitously from above 12% to just 4%.

It’s likely to get worse with the ongoing investment spree in green and critical technologies, where as aforementioned, the limits to supply are becoming evident.

As Setser and others have pointed out, a major source of competitiveness for Chinese manufacturers comes from their access to directed credit in the form of cheap equity and debt, provisioned by local governments and state-owned banks. But major fault-lines are now showing up there. As the real estate market flounders, the local government’s access to resources is drying up. And mounting defaults by real estate and manufacturing firms are starting to stress the financial system.

With the deficient domestic demand and rising restrictions on export markets, the export-driven model appears to be at its last legs. Rebalancing towards domestic consumption is the only way to absorb the massive savings.

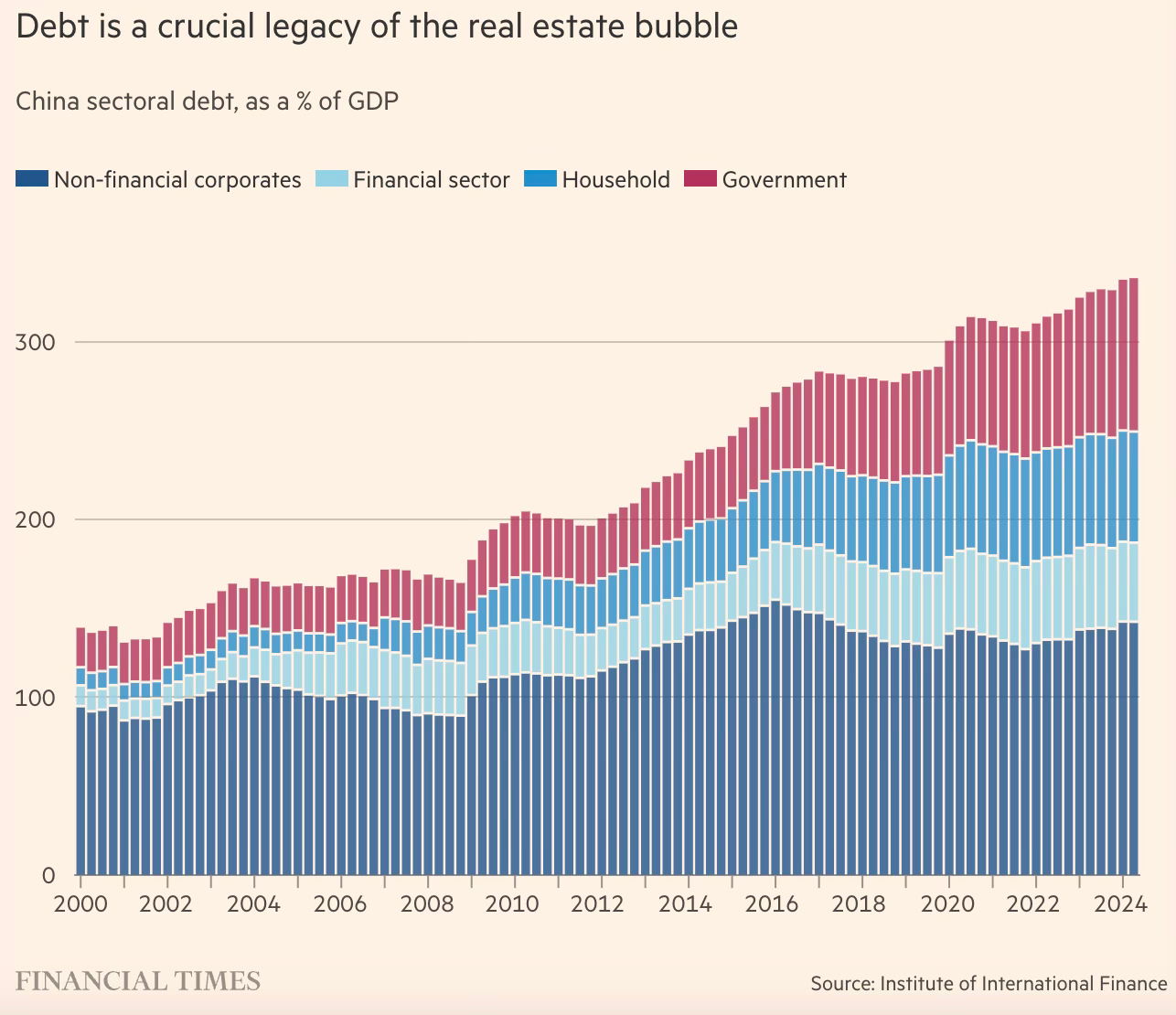

The final piece is the debt overhang facing local governments and financial institutions. Since 2010, government debt has risen from 34% of GDP to over 86% today, and this is most likely a gross underestimate given the large value of off-balance sheet debts of local governments in the form of local government financing vehicles (LGFVs).

The biggest challenge for the central government is in the management of real estate prices, which are critical to local government revenues. It’s estimated that property made up 23-27% of GDP from 2011-21, absorbing nearly half the total domestic savings of around 45% of GDP. This degree of importance of real estate places Beijing in a catch-22 situation.

Elevated real estate prices are central for not only future revenue mobilisation but also to ensure debt repayments. If the property bubble gets deflated abruptly, it can result in a cascade of local government defaults, failure of banks, investment cuts, and job losses. It’s hard to manage such downward spirals.

The counterparties to real estate and other corporate debt are financial institutions. Logan Wright writes in a Rhodium Group report

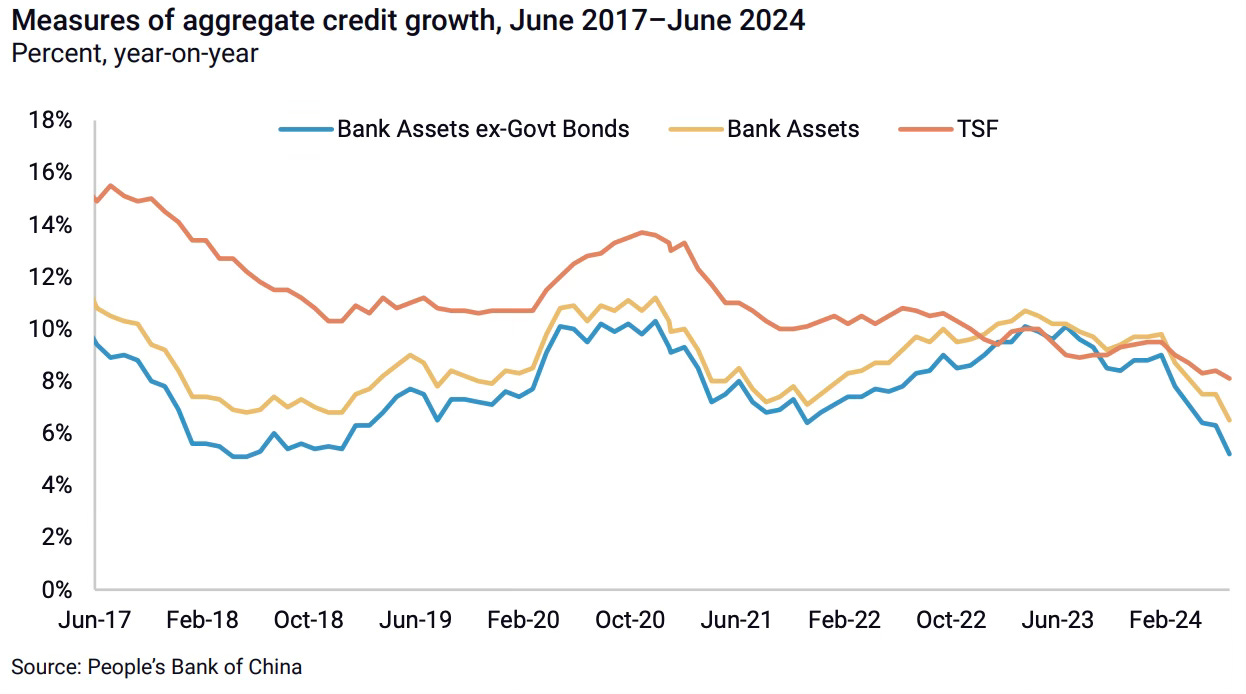

China saw the largest single-country credit expansion in over a century, adding $24 trillion in new assets over the eight years from 2008 to 2016, around one-third of global GDP. Banking system assets now total $59 trillion as of June 2024, over three times the size of China’s economy and around 56 percent of global GDP. In comparison, China’s real GDP grew by $6.1 trillion between 2008 and 2016, and a further $7.1 trillion between 2016 and 2023. China has by far the largest single-country banking system in the world in terms of assets. US banks hold around $23.4 trillion in assets, but the US has a far more diversified financial system than China. That volume of lending by Chinese banks was extended primarily on the basis of government guarantees rather than the potential financial returns of the underlying investments. As a result, this credit explosion generated significant numbers of loans that may have been made to “safe” state-owned companies, but they constantly require loan rollovers and extensions. A financial system this large and this impaired can no longer generate the same pace of credit and investment growth as it did in the past…

Bank profit margins and credit growth in China have already slowed significantly. China’s overall credit growth averaged 18 percent from 2007 to 2016. Its slowdown in credit growth began in earnest with the deleveraging campaign from 2016 to 2018, and since then credit growth has averaged just over 9 percent. Banks’ average net interest margins on lending have fallen from 2.77 percent in 2012 to 1.54 percent in the first quarter of 2024, according to data from China’s banking regulator.

The financial system too therefore has hit its limits in sustaining the government’s investment-driven economic growth strategy. This is showing up in “the collapse in property investment, a slowdown in local government investment, and rising local government fiscal pressures”.

Beijing will be able to kick the can down the road with adhoc policy interventions like the recent monetary stimulus. Perhaps it’ll supplement with fiscal stimulus. It might reverse policy and prop up the real estate sector. Whatever the measures, there cannot be any substitute to rebalancing away from investment to household consumption for China to address its problems and achieve a sustainable growth path. This will be the biggest challenge yet for China in the last several decades and should become the top most priority for the government.

No comments:

Post a Comment