Capitalism is undergoing a quiet transformation as institutional private capital increases its ownership footprints across vast swathes of the economy. What are its implications?

John Gapper in FT has an excellent article highlighting the journey of Pimlico Plumbers, a family-owned plumbing and home repair service founded in 1979 by Charlie Mullins, and which was sold three years back to US home services platform, Neighbourly, owned by the PE firm KKR for £140 mn. The firm distinguished itself by the reliability and quality of its service and charged a high hourly rate to well-off customers.

Pimlico was a pioneer of charging well-off customers a higher hourly rate for reliability. Instead of plumbers who turned up late if at all, and exploited their customers’ ignorance of home piping to overcharge, Pimlico offered a consistent service from uniformed engineers who were polite and cleaned up their mess afterwards. It was a simple formula, but someone had to reform a fragmented, opaque cottage industry and Mullins was the innovator. Private equity has now seen its own opportunity, having rolled up family-owned veterinary and dental practices. Brookfield Asset Management struck a £4bn deal in 2022 to acquire HomeServe, the UK home repairs cover group. As family founders of home services companies approach retirement, investors want to increase the scale of the industry, while maintaining quality.

The article informs that the Mullins family (of three generations) are now going back to their business after the expiry of a three-year non-compete clause by launching a new home service firm, WeFix.

WeFix bears all the hallmarks of his formula for Pimlico: a call centre on the premises, vans waiting to be cleaned and valeted, a space for apprentice training. It will squarely target the same group of customers… If anything, it will be more elite: the new business plans to charge £180 an hour for daytime jobs, compared with Pimlico’s £125 hourly minimum for plumbing. This will enable its top engineers, classed as self-employed with some workers’ rights after a 2018 Supreme Court ruling involving Pimlico, to earn between £150,000 and £200,000 per year... The family has become a dynasty, with 15 members, including partners, now involved in WeFix. Scott is chief executive and Ashley managing director; Charlie has no stake, but the company is infused with his philosophy. Scott compared its approach to personal service with the luxury department store Harrods: “You know the prices, you know the quality, you know you’ll be looked after.”

But while they have high ambitions for quality, they are modest about WeFix’s potential size. They are keener to replicate and refine the old Pimlico model than to extend it further. Charlie said that Pimlico had about 250 engineers when he sold it — many more than the average home services business — but standards had been slipping. “We took on some people who were not up to our standards. We fell into the trap of growing too fast because demand was so high,” he said. They intend to proceed more slowly this time, aiming ultimately to reach about the same size as Pimlico. WeFix London will not expand beyond the city: the family feels most comfortable on its home turf.

Interestingly, Charlie Mullins, the founder and patriarch, does not think the PE model will work in the business.

A family business is more personal, more caring, we put more into it.

The case study points to an important and less appreciated trend in the economy, especially pronounced in the United States.

Historically, most of the regular consumption services for households and offices were provided mainly by small family-owned shops (mom-and-pop shops) and small businesses. They include clinics and hospitals, pharmacies and diagnostic facilities, schools and colleges, bars and restaurants, old age homes and terminal care services, security, home repairs and other services, office services, personal care (salons, beauty and cosmetic centres, nails etc.), veterinary care, local sports teams, and so on.

Now, after establishing their dominance in finance, technology sectors, startups, real estate, infrastructure etc., PE firms are expanding into these markets. They realise that these market segments that serve people’s daily lives offer low-risk and stable revenue opportunities. No matter what happens, good times or bad, there will always be stable demand for these goods and services. They are the so-called essential services with very low elasticity of demand.

There are at least three concerns I have with the rise of PE firms in these business areas. Is it the right kind of capital to finance these activities? Can they offer the kind of quality of service that many of these activities require? Can they ensure the kind of responsibility to its customers, workers, and communities that local or public capital provides?

In the spectrum of financial intermediation (compared to debt, personal financing, and public equity), PE firms provide equity and represent high-net-worth individuals (and increasingly institutions). By its very nature, it’s capital with high risk appetite and searching for high returns. Further, the high fees demanded by its managers, add to the returns expectations. Can the kinds of essential services like those mentioned above command the sort of margins to justify these return expectations?

If not, then the only way the returns will be generated would be by asset stripping and squeezing the firm’s cash inflows and passing the parcel till it becomes insolvent. The incentives of the PE fund managers and investors are aligned towards pursuing such practices. This blog itself has documented several examples from recent times of such practices.

Most of the services of the kind mentioned above demand some form of personal connect. The family-owned provisioning of these services provided some neighbourly personalised touch that disappears with the distant ownership by PE investors and their fund managers. The PE fund managers invariably rely on the standard approach of giving targets for the number of customers served and their unit efficiency of service, and minimising the cost of this service delivery while maximising the prices. It’s impossible to do all this and also maintain quality and the personalised care.

Finally, the nature of the PE ownership almost eliminates any fiduciary relationship between the company owners and its customers, employees, and communities. The single-minded pursuit of cost minimisation and profit maximisation leaves both customers and employees worse off. The diffused ownership, portfolio approach of PE funds, and their outsourced management also mean that the PE firm can cut losses and exit a company with fewer restraints and costs.

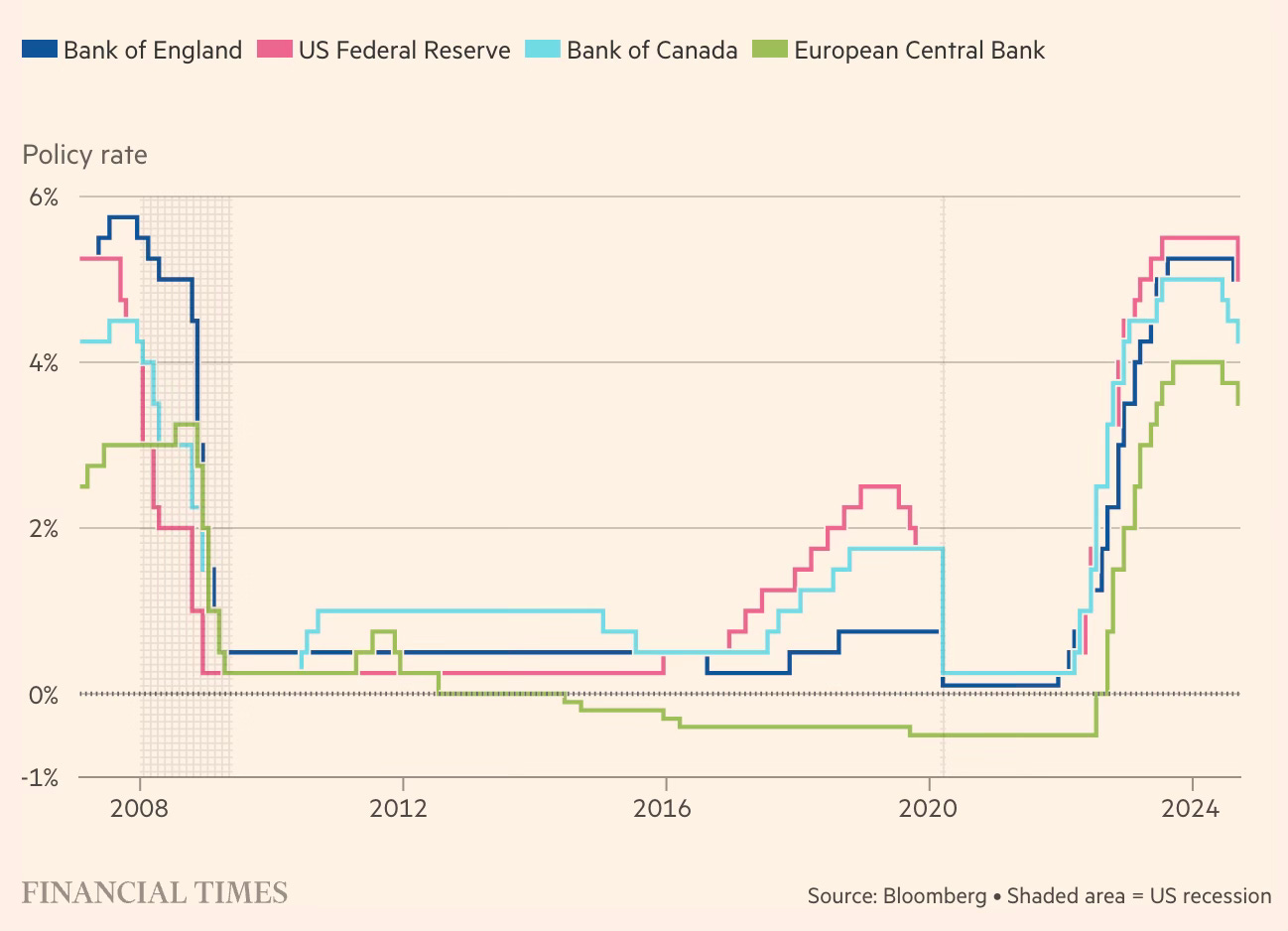

As to what’s driving this kind of capital, I can think of two important contributors - ultra-cheap capital and regulatory arbitrage. Since the Global Financial Crisis (or perhaps since the turn of the millennium), barring limited periods, the advanced economies led by the US have experienced extraordinary monetary accommodation by central banks.

The low interest rates were a big boost to the PE business model that relies on extensive use of leverage to juice up returns. It also allowed PE firms to attract massive volumes of capital from both wealthy individuals and institutional investors (searching for yield in times of low fixed-income returns), which in turn found its way into these newer and stable return market segments.

Spurred by imperatives like financial market regulation, trade standards, and addressing climate change, governments have become more invasive over the last two decades in terms of regulations and compliances. Accordingly, the costs of being a small business (and a public limited company) have steeply risen whereas the advantages of being a privately held company have increased just as sharply. This attractive regulatory arbitrage opportunity even incentivizes firms to remain private and exit the public markets.

As long as PE was confined to a few sectors and its investors were just ultra-high-net-worth individuals, it might have been all right to allow light-touch regulations. But with PE ownership expanding its roots across the economy and with institutional investors like pension funds and insurers contributing an increasing share of PE investments, there’s a greater case for regulation of PE firms on similar lines as public capital. In fact, with an increasing share of capital from tightly regulated institutions, it may no longer be appropriate to even describe PE as private capital.

No comments:

Post a Comment